Back to selection

Back to selection

How to Appreciate the Techno-Aesthetic Breakthroughs of Ang Lee’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

Tonight, Friday, October 14, 2016, the Film Society of Lincoln Center makes cinema history with the New York Film Festival’s world premiere of Ang Lee’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, presented at the 600-seat AMC Loews Lincoln Square 13 IMAX theater on its 100-foot-wide screen, the largest in North America.

The brief on this technological milestone? Images shot and projected at 120 fps, dual 4K RGB laser projectors that display wide color gamut and high dynamic range, bright RealD 3D, 12-channel audio with overhead speakers plus sub-bass.

Talk about immersive!

And what of the film itself?

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk is adapted from Ben Fountain’s esteemed 2012 satirical war novel (think Joseph Heller). It tells the story of a 19-year-old Iraq War active-duty soldier, Billy Lynn, and his squad on leave from the battlefield for a two-week media tour. Having been caught on camera in a frenzied firefight with the enemy by an embedded Fox News crew, they’re to be honored for special bravery at a Dallas Cowboys Thanksgiving Day game during the halftime entertainment, featuring Destiny’s Child no less.

Ang Lee previewed 11 minutes of his latest film last April, to small groups at NAB in Las Vegas. I was fortunate enough to be included. This sneak peek required creating an ad hoc 3D projection room at the Convention Center, complete with dual 4K Christie RGB laser projectors — RGB laser is a must, I’ll explain below — and a deposit box to recycle Dolby 3D glasses. In introducing the clip, Ang noted that color correction was not yet complete. But you could have fooled me… I thought it was perfect.

Then again, I wasn’t about to be distracted by trifles such as tech details. I was too heavily absorbed by an external narrative unfolding with the vividness of internal memory. (A goal cinema has always aspired to.)

It’s halftime, night has descended, and onstage, Billy Lynn’s squad stands at attention as Destiny’s Child shimmies and serves up their hits — to the accompaniment of flashpots and celebratory fireworks that cause these rattled young warriors, fresh off the battlefield, to flinch involuntarily with anxiety.

Billy slips into a violent flashback. His image onscreen seems to hang in the air, even as it melts into a hyper-real, sun-drenched Afghan village, half a world away. Ear-splitting bullet hits crackle and explode the dust around us as Billy and his buddies come under close fire. You almost feel the midday heat shimmering off the mud-brick houses, so bright does the day-exterior detail appear.

Again, you realize this is not an ordinary motion picture experience.

Try to imagine a super high-resolution VR experience minus the goggles, with your head fixed in one direction, toward a very big field-of-view. Crack, crack of a distant rifle and two bullets zip by, too close for comfort.

What on earth did Lee use to shoot native 3D at 120 fps?

Answer: a matched pair of Sony F65s. Not exactly a lightweight hand-held rig. In fact, comparable in mass to those refrigerator-sized blimps used in the early days of sound film. You remember, the ones so bulky that stodgy fixed framing replaced playful silent-era traveling shots, another example of style born of camera (im)mobility?

There are shots in Billy Lynn that pass as hand-held — there’s a story there — but I did notice a plurality of sequences made with a locked-down camera. I also noticed something else. Sequences that exploited a locked-down camera. For instance, in some shots of the halftime show, with entertainment in motion onstage and on the field, we see the hoopla through a large scrim or some other transparent visual impediment or both — evoking a sensation of planes of action arranged by spacial depth. (If you went to film school, you know this is called mise-en-scène.)

One of these scrims consists of a series of enormous outdoor LED video displays surrounding the Cowboys Stadium stage, which are actually matrices instead of solid planes, the better to see through from behind. (I won’t alert the anachronism police to the fact that such large outdoor LED screens are ten years in the future if you won’t.)

I suspect that Billy Lynn’s enhanced brightness, distance detail, color definition, and clearer 3D effect all served to reawaken my eyes to the elemental graphic power of mise-en-scène. I was really taken by this.

But a cinematic play of planes would be no accident. Foremost, Ang Lee is an artist. Not a technologist. Which is why his experiments with 4K @ 120 fps and 3D have produced such compelling results. In the hands of a technologist like James Cameron or Douglas Trumbull, the results would have been different. No doubt a degree of show-offy tech ostentation would have prevailed. In Billy Lynn, technological advances seem to exist only to serve narrative ends. This reflects the thought Ang Lee has evidently put into their meaning and use.

I don’t mean to disparage the contributions of the likes of Douglas Trumbull. In 1987, I visited his Showscan showcase theater in L.A., saw a demonstration 70mm print projected at 60 fps. My lasting impressions were the audible chatter of the accelerated projection system (as if imminently shredding the film) and the sensation onscreen of a veil lifted, where dirt, scratches, film grain, and the surface of the acetate print seemed to vanish, leaving behind a distinct clarity — as if you could walk into and through the screen. Admittedly Trumbull was ahead of his time. But as an indie filmmaker, I couldn’t get past the practical costs of shooting in 65mm at 60 fps, nor the hidden costs like shipping those massive reels! In fact, no feature film was ever produced using Showscan, which in the end was relegated to short ride films in theme parks.

The Showscan image itself was circumscribed by the output of xenon projectors (despite a unique single-bladed Showscan shutter), conventionally designed to fill screens with 16 foot-lamberts of brightness according to SMPTE projection standards. Showscan also relied on conventional film prints, with far-from-perfect subtractive color reproduction.

Ang Lee’s achievement will no doubt also be likened to Peter Jackson’s foray into 3D and 48 fps origination with his Hobbit trilogy — a comparison which, upon scrutiny, collapses. For one thing, 48 fps is merely double 24 fps. It even falls short of the 60 Hz field refresh rate we’re used to in the U.S. when watching HD cable or ATSC digital television. Therefore no big deal, in my opinion, despite commotion at the time.

Needless to say, Ang Lee’s 120 fps hikes cinema’s nearly century-old 24 fps by a factor of five! Like it or not, this has visual impact.

Secondly, most, if not all, commercial digital projectors that displayed the Hobbit series were 2K, not 4K, as were the DCPs themselves.

Thirdly, while Jackson and DP Andrew Lesnie captured 5K RAW files with RED Epic cameras and undoubtedly placed a premium on the quality of their images — I don’t know whether or not they utilized RED’s HDRx high dynamic range technique, which requires a secondary exposure — viewers in theaters would see only 7 foot-lamberts of brightness. Yes, only half the long-established SMPTE screen brightness standard! Regardless of whether they wore polarized ReadD or dichroic Dolby 3D glasses.

This is because in commercial 3D projection, a single projector is used to project alternating right-eye and left-eye images. Each eye receives only half the image pair and half the brightness. Polarized 3D projection like ReadD furthermore requires a high-gain (high reflectivity) “silver” screen, which typically contains a hotspot. (These gray screens, when used incorrectly for 2D projection in commercial cinemas, cause film images to look dull and flat— a pet peeve of mine!)

Single-projector 3D and the resulting anemic screen brightness explain why all current 3D films look desaturated and murky compared to non-3D films properly projected onto low-gain, matte white screens. (Once you become attuned to this phenomenon, you can’t “un-see” it.) This is why despite the best efforts of Peter Jackson and Andrew Lesnie in The Hobbit series to capture as broad a tonal range as possible, not even a conventional dynamic range was possible onscreen. Not with a dark 7 foot-lamberts!

One solution to this is the use of dual projectors for 3D, one for each eye. This would double today’s 3D screen brightness, raising it back to the traditional level of 16 foot-lamberts. (Naturally, this solution also doubles the cost of projection.)

Another solution is to adopt a projection technology with greater light output than legacy xenon lamps.

That would be RGB laser projection, capable of up to 50% more light output than xenon at 1/5 the power draw. (Not to be confused with Laser Phosphor projection, a competing, cheaper technology with color and aging drawbacks that render it an interim solution at best. Expect RGB laser costs to drop over the next five years, and Laser Phosphor to fade away.)

Please don’t get the idea that RGB laser projectors shoot laser beams from their lenses. The three lasers (red, green, and blue) are light sources only, which are combined to form intense white light — diffuse, no longer coherent that functions like the output of a conventional projector lamp house.

Comprising three narrow bands of wavelengths, this composite white-light source is considerably less wasteful than a full-spectrum white-light source, most of which is thrown away by subsequent filtering anyway.

More efficient output from each RGB laser projector enables not only brighter 3D images but also reproduction of an extended high dynamic range (HDR), based on new standards for brighter highlights that better resemble those experienced naturally by the human eye.

In terms of color gamut, these three narrow-bandwidth, additive colors act as precise primaries, negating color cross-talk and forming an unprecedentedly large gamut of real-world colors. Perfect for new wide color gamuts (WCG) that very nearly match the human visual system.

As noted at the top of this blog, the October 14, 2016, premiere of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk also marks the debut of a spanking-new IMAX dual 4K RGB laser projection system — one for each eye — at AMC Loews Lincoln Square 13 IMAX theater in Manhattan.

IMAX, in collaboration with Barco and Audyssey Laboratories, spent years developing this unique system, exclusively licensing about 100 laser-projection patents from Kodak in 2011. They are committed to 3D in 4K.

Because RGB laser projectors can cost five times a conventional digital projector, you can expect a premium ticket price for this premium IMAX experience. That’s their near-term business plan.

Their long-term business strategy: let Netflix or Amazon or YouTube try to match the visceral thrill of dual 4K RGB laser projectors lighting up an enormous 3D screen, wrapped in 12 channels of thunderous audio.

Just like how widescreen color, Cinerama, and 3D helped beat back TV in the early 1950s, right?

In an ironic twist of history, this time it is cinema that is trailing TV, with its steroidal new standards.

The DCI specs that gave us DCP and the DCI-P3 color space used in theaters are more than 10 years old now. They were based upon creating a digital motion picture image “better than 35mm film.” However, technology never sleeps. Four years ago the ITU (International Telecommunications Union) put forth Recommendation 2020 for Ultra-High Definition TV (UHDTV), with specs for 4K and 8K.

Rec. 2020, as it’s known, defines progressive frame rates up to 120 fps and several formats for HDR.

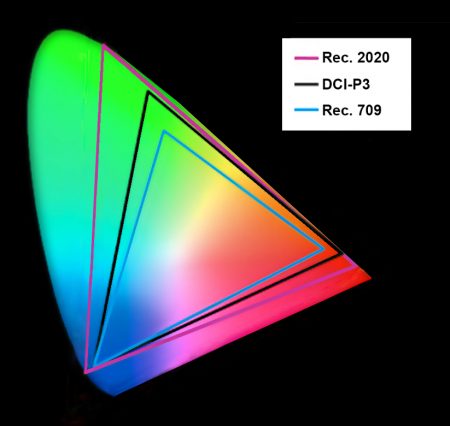

In terms of color space (gamut), Rec. 2020 blows past Rec. 709 for HD, which covers roughly 36% of the human visual spectrum. Rec. 2020 instead covers 76% — twice the colors of Rec. 709 — and smokes the current DCI-P3 color space for digital projection, which covers only 54%.

In another irony, Rec. 2020 is described as an “aspirational” standard because the only technology that can so far actually achieve it is RGB laser projection.

Ang Lee, you see, has laid down the marker for future works of Cinema.

Sony’s TriStar Pictures will release Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk in theaters on November 11, reportedly in both 2D and 3D. Four more cities with IMAX theaters and dual RGB laser projection will project the intended version, including Los Angeles, Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei. Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk is a British-American-Chinese co-production.