Back to selection

Back to selection

Keystone Cop: Why 1.66 and 1.78 Aspect Ratios Are Often Misprojected (And How to Fix That)

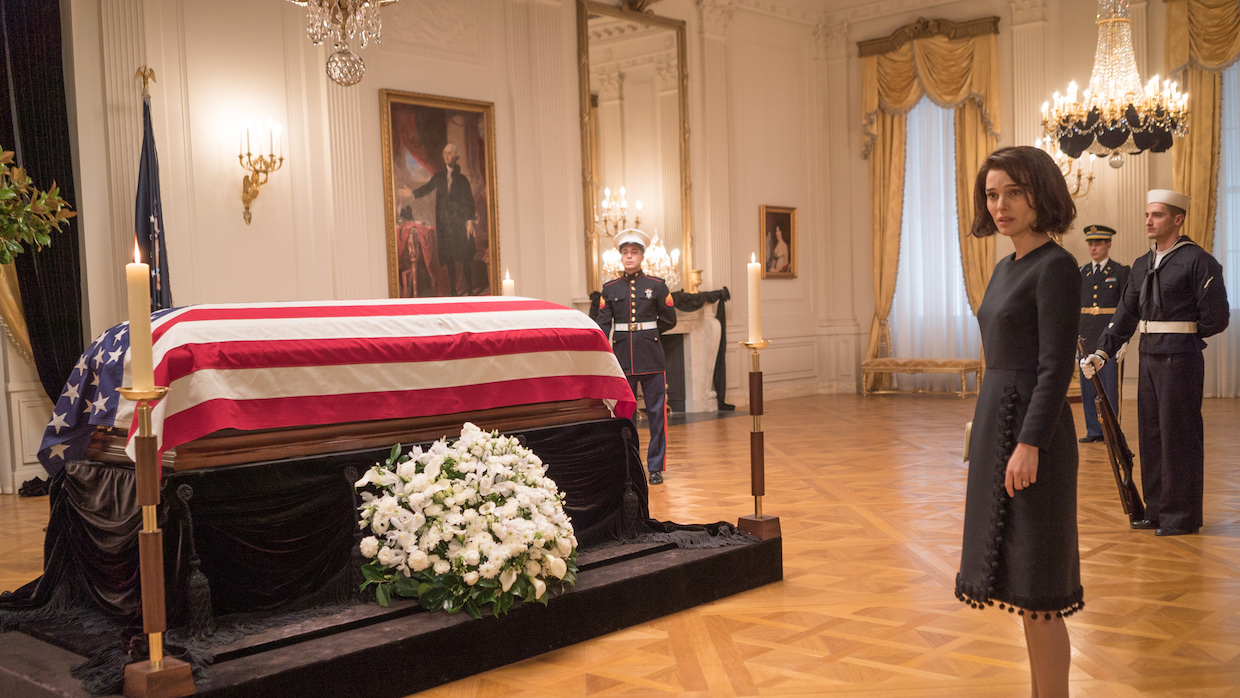

Jackie (Photo by Bruno Calvo, courtesy of 20th Century Fox)

Jackie (Photo by Bruno Calvo, courtesy of 20th Century Fox) Jackie, Fox Searchlight’s best hope for 2016 Oscar glory, will be improperly projected throughout the world. There will be the usual projection mistakes and corporate carelessness that have become the norm in today’s multiplexes, but Jackie’s 1.66 aspect ratio will be presented keystoned more often than not: instead of a narrow rectangle that is 1.66 times longer than tall, the tops of the image will either curve inward or outward in relation to the screen. It’s an easily corrected mistake that is being ignored because of laziness. Since most projection booths are devoid of projectionists who can fix the problem, what can be done to minimize the damage?

You may be familiar with vertical keystone images from crummy office projectors, where the top or bottom of the image is smaller or larger than the opposite side. The image resembles a trapezoid instead of a rectangle or square. This occurs when a projector is placed at an angle that is not centered onto the screen surface. Imagine a projector placed on a desk, pointed upward at a screen that rolls down from the ceiling. Most consumer and higher-end DLP (Digital Light Processing) projectors, which are not designed for digital cinema, contain electronic keystone correction options that allow for the adjustment of the image to compensate for unusual angles. The usual standard for keystone correction is a 35 percent offset above or below the center of the screen. It morphs the image so that, when viewed normally, the image begins to tilt backward or forward at an angle. In creating a geometrically correct image, the electronic keystone correction also creates a loss of image resolution that is, in my experience, not perceptible for consumer playback of presentations and high-definition films.

Because of this loss of resolution, the DCI (Digital Cinema Initiative) projection standard does not allow compliant projectors to feature an electronic keystone correction. Instead, most DCI projectors and lenses allow for a lens shift that allows a similar 30 percent vertical image adjustment. Instead of electronically adjusting the image to tilt forward or backward, the lens shift option allows the projector to move an image in any two-dimensional Cartesian direction.

Most traditional theater construction, pre-2010, made space for the projector inside a booth behind the auditorium. Most image throws fit within the 30 percent image adjustment because older celluloid film projectors had pretty strict requirements for placement. Some older movie palaces with multiple balconies weren’t particularly suited for celluloid projection and often had projection issues where actors onscreen looked stretched thin. Nobody ever said the past was perfect. Most theaters weren’t movie palaces; they were single-level affairs with either flat or raked seating and an elevated screen.

New theaters designed around digital cinema projection have attempted to minimize the space needed for projectors and projection booths, with many projectors installed in the ceilings of auditoriums and the projector and server control located in an IT closet nowhere near the theater. Additionally, stadium seating has increased the height of seats in relation to the screen. This combination leads to a significant keystone effect.

To compensate for irregular image geometry, each individual auditorium has a custom screen file programed onto the projector, which blanks or crops the sides of the image until a geometrically consistent image is created; the tops and bottom of the screen are the same length. If the bottom of the image is four vertical lines longer than the top of the image, those four vertical lines on either side of the image (two on each side), each 1080 pixels in length (or 0.4 percent of the total image size), are cropped. There is no determined maximum for cropping the sides of the image, but generally anything past 3 to 5 percent of the image will begin to disrupt screen compositions and titles.

All digital cinema auditoriums should have screen files for 1.85 and 2.35 aspect ratios. They may also have settings for 1.78 alternative content, which can be anything from a Blu-ray player to satellite/cable television. In some rare cases, theaters may have support for letterboxed Blu-rays, which blow up the image so the letterbox is no longer visible and the image takes up the entirety of the scope screen setting. Most of the content produced by American studios fits within these aspect ratios.

There are outliers that don’t fit these parameters. Independent film all over the world is shot with inexpensive HD cameras that have a native aspect ratio of 1.78. Older films before 1953 are meant to be projected at a 1.33 aspect ratio, and most European cinemas adopted 1.66 as their widescreen standard instead of the American 1.85. Most of the time, DCPs of restored classics and European films are played in American theaters in the 1.85 setting. While the 1.85 image is cropped to be geometrically consistent, the other aspect ratios exist outside of the established crop. You need to crop a larger percent of the image in order to fine-tune and adjust a keystoned image. In theory, theaters should have a preset for all of these different aspect ratios and mask everything accordingly. It is not a time-consuming process and doesn’t require an extensive amount of technical knowledge.

Distributors such as Disney often send out individual framing charts with films that feature horizontal lines with an onscreen notice saying the line “must be visible regardless of keystone.” Fox Searchlight included a 1.66 framing chart for Jackie as a separate file on the DCP drives sent to theaters. How many theater managers actually decided to load up the framing chart and create a scene file for one of the year’s most prestigious releases? Imagine if an art gallery told painters they only had two frame sizes and their work had to fit inside of one. We live in an age of cinema as square peg in a circle hole, a two-size-fits-all hellhole that demands conformity.

As film patrons, there isn’t much that we can do. We can support great theaters and institutions across the country, such as the Belcourt in Nashville, the Music Box in Chicago and the Center for Contemporary Arts in Sante Fe, that care about exhibition. We can educate ourselves about what a film should look and sound like and complain when they don’t reach our standards. We can hope and demand change all we want, but I’m not optimistic.

Filmmakers can demand all of those changes and aim to exhibit their films in spaces that care about how they look. I’ve had filmmakers tell me that title safe doesn’t matter with a digital projector and yet get confused emails and phone calls when their subtitles or credits are cropped in certain theaters but not in others.

Ultimately, though, filmmakers want to get their films in front of as many people as possible. The following are some ideas for working within the parameters of today’s digital projection to ensure the best possible presentation of a film.

For filmmakers still shooting a film in HD (1.78), my suggestion would be to protect for 1.85 during production and blow the image up to fit a 1.85 frame. I’ve seen filmmakers place gaffer tape on their LDC viewfinders to note the margin areas. More advanced HD cameras, such as the Canon C100, have aspect ratio markers that appear on the viewfinders as semi-transparent lines. The image output will still be 1.78, but editing software can place your footage in a 1.85 (or 2.39) container and blow it up accordingly. This has become a fairly common method for creating scope pictures but filmmakers looking to shoot in 1.85 flat should also adopt it.

Filmmakers shooting on higher resolution cameras should note that they have the same aspect ratio markers and make sure to protect for one aspect ratio. Various RED cameras feature a frame guide that allows for the protection of various aspect ratios because the camera’s native aspect ratio is 1.90. The 1.90 aspect ratio is great for post purposes, since it allows for the cropping of a 1.85 or 2.39 image and gives filmmakers the flexibility to reposition frames. I would advise against creating an exhibition copy of your film at a 1.90 aspect ratio, also commonly referred to as a full container. I am currently not aware of any theater that is set up for 1.90 playback and most theaters will play back the film at a 1.85 aspect ratio, which will cut off the sides of the image, or at a 2.39 ratio, which will cut off the tops and bottoms. Jurassic World was delivered to theaters as a letterboxed 2.00:1 aspect ratio that was intended to be projected in a flat setting. For Jurassic World, the decision was made because it would make the dinosaurs look larger onscreen. Remember that each film has its own distinct look, but there is nothing inherently cinematic about a letterbox image despite what television, commercials or tentpoles may tell you.

Title designers and graphic artists also need to think about how animation, graphics and texts are displayed onscreen and ensure they are properly displayed no matter which theater may or may not have a crop. Both title safe (10 percent around the border) and action safe (5 percent around the border) markers are options in most editing and graphics software. My suggestion would be to put all essential graphics inside an action safe border. I personally use a title safe graphic margin of 10 percent. If, worst case, an image is cropped 5 percent, graphics will still appear onscreen.

These aren’t issues that filmmakers will have to deal with when they post their film for home or internet viewing. This is a far change from the early days of home viewing, where films were cropped in a process called pan and scan to fit the 1.33 dimensions of pre-HD television. Now most monitors are 1.78 and the majority of distributors are okay with their films being released with the necessary letter- or pillarboxing. It’s not a perfect environment: a lot of HBO’s back catalogue of films are still shown at incorrect aspect ratios, but it is certainly an improvement.

Can we expect a similar improvement in the theater? Most of my writing for Filmmaker has been concerned with how the digital cinema transition has been a top-down decision in which the primary interest was in reducing costs for corporate conglomerates. The transition’s implementation has not had an interest in the artistic and creative side of filmmaking and, at times, it seems like the transition has been wielded as a weapon against independent film. It is curious that a Fox Searchlight-released, U.S./Chile/France production that decided to use an unorthodox aspect ratio is the unintended victim of the transition. Was there anyone on the Jackie team that considered the potential problems of a 1.66 aspect ratio for U.S. audiences?

My theory has been that film industry professionals rarely see any films with the general movie-going public. These are the benefits of private screening rooms and at-home screeners; there seems to be a disconnect between how a production team and the industry views a film versus everyone else. Even if filmmakers and executives are watching films in their hometowns of Los Angeles or New York, the quality and level of projection at multiplexes is higher in these cities than the rest of the country. It’s why a director like Christopher Nolan has championed celluloid projection for his projects: the guarantee that the theaters showing the nondigital version will have a pilot behind the wheel while everyone is being automated into an abyss.