Back to selection

Back to selection

Laura Poitras Talks Assange, Her Final Version of Risk and Trump’s Tax Returns

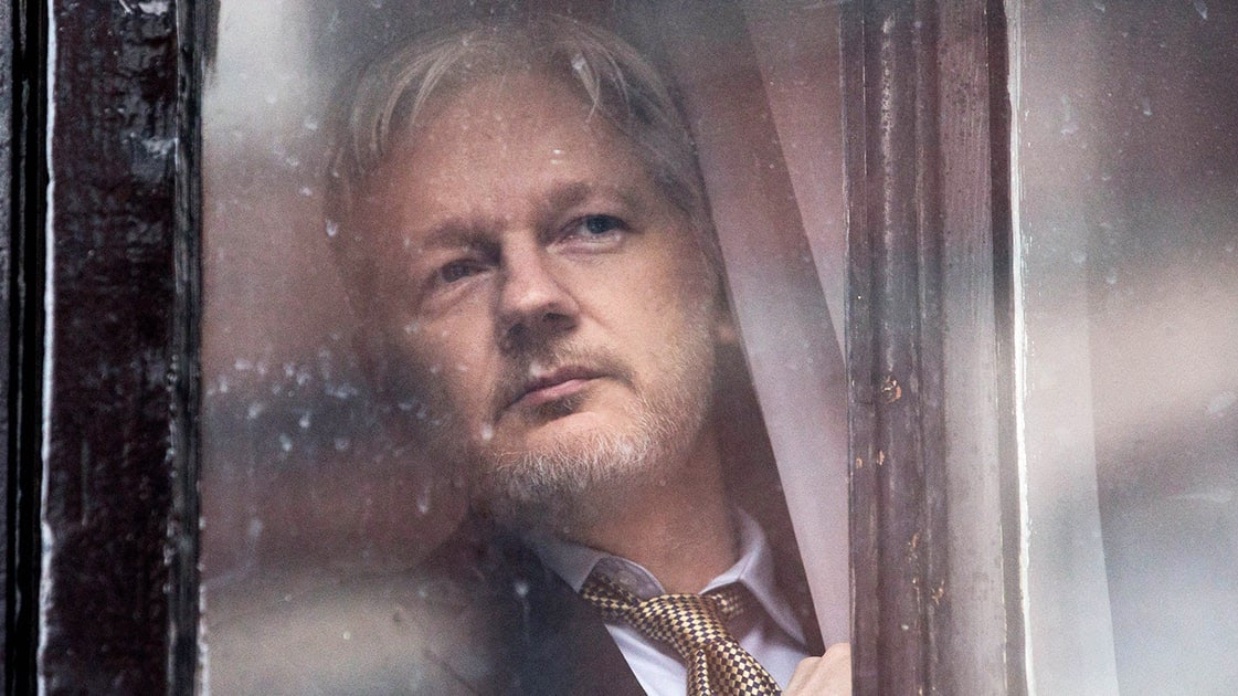

Julian Assange in Risk

Julian Assange in Risk Just now released on Showtime, Laura Poitras’s Risk, which found its way to theaters in May via upstart distributor Neon, is in a vastly different form than when it premiered last year in Cannes. The documentary traces a thread running counter to the moral certitude heard from our politicians, mostly on the right, about the role of leaks in degrading democracy. Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, the film’s primary subject, has been confined to the Ecuadorian embassy in London for nearly five years following allegations — and, later, charges — of sexual assault against two Swedish women. (The rape investigation was recently dropped by Swedish prosecutors) Under a cloud of potential extradition to the U.S., Assange continues to deny these allegations, even as the statute of limitations on several of them has passed.

Until WikiLeaks became embroiled in the scandal regarding Russian hacking and interference with the U.S. 2016 election, Assange’s public profile seemed to be on the wane, but with the film’s release and increased pressure by the Trump administration to punish leakers, the ever divisive journalistic and political figure is likely to come under even new scrutiny.

Risk‘s footage was initially going to be bundled with the Snowden material that made up her Oscar-winning Citizenfour, but eventually Poitras realized that the two threads would be too ungainly if wedded and would have to remain separate projects. Opening in 2011, the films drops us into a scene of Sarah Harrison, Assange’s closest WikiLeaks collaborator, calling the U.S. State Department and asking to speak to Hillary Clinton about several secret cables that another entity is poised to release. In scenes of startlingly immediate vérité, Risk details the inner workings of WikiLeaks over several years and the personal toll it takes as various international state actors attempt to impose a muzzle on the site’s activities.

In my interview with Poitras this past Spring, the filmmaker seemed ambivalent about Assange’s role in the ongoing Russian hacking scandal, as well as the possibility of state actors being in cahoots with WikiLeaks to disrupt the U.S. election. The filmmaker suggested she began making Risk in a much different techno-political landscape, one rife with hopeful possibilities in the wake of the Arab Spring and Chelsea Manning for the possibilities of the internet being used as a tool for people to mobilize around democratization and whistleblowing. As the film arrived in theaters, Poitras admitted to finding that same landscape, where nation states marshall the internet for their own obfuscatory, perhaps anti-democratic designs with increasing frequency, “terrifying right now.”

Poitras acknowledged that the DNC’s hacking and Wikileaks’ involvement in the unveiling of John Podesta’s emails “functions as a third act which sort unfolded after the Cannes screening — of course I needed to incorporate it.” When I asked her about the most memorable of the new crop Field of Vision shorts — Maxim Pozdorovkin’s “Our New President,” a hallucinatory found footage mashup of Russian state television’s evolving coverage of Donald Trump’s young presidency with bizarre and occasionally chilling messages to the newly elected President from ordinary Russian citizens and bureaucrats — Poitras mused, “The subtext is this crazy panic about Russia right now, which is maybe [part] based in fact and a lot of it based in people getting spun up in issues.”

While Risk has not necessarily grown more critical of Wikileaks in its new incarnation, the private behavior of Assange is viewed with far more scrutiny in the new cut. Poitras was pressured by Assange and his legal team to remove scenes where he discussed the Swedish case before the film’s premiere in Cannes last year. According to Poitras, the night before the film’s unveiling at Cannes in 2016, Assange sent her a text message, one she now includes in the film, which read, “Your film is a severe threat to my freedom, and I plan to treat it accordingly.” After that premiere, which Poitras admits to having doubted should have gone forward at all, some observers suggested the film didn’t do enough to address the Swedish allegations. Poitras has doubled down in the new cut, increasing the film’s focus on Assange’s contradictions, vanity, lack of contrition and unwillingness to be forthcoming concerning the Swedish matter.

But, according to Poitras, it was new revelations about another of the film’s characters that led her to continue working on the movie. “Two weeks after the Cannes screening was when allegations about [transparency and privacy activist] Jacob Appelbaum were made online, and that’s when I knew I had to go back,” Poitras told me. Feeling she had no longer made “an honest film,” she was prepared to walk away from it entirely, refusing distribution offers unless she was able to get the gender politics within the film right. “I don’t want to pull punches, but I’m not interested in taking anyone down,” Poitras said, pausing for a moment, considering her words carefully. “I’m interested in having productive conversations about these issues.”

Poitras’ reworking of Risk finds the filmmaker personalizing her depiction of the WikiLeaks saga. The new incarnation eschews the chapter-like structure in the Cannes cut for a far more sweepingly linear narrative. She occasionally punctuates this streamlined telling with bits of her own unusually personal narration, both in voiceover and in on screen text, pulled from a production diary she kept while shooting. Revealing her own relationship with Appelbaum and increasing discomfort with how he had treated various associates of his, Risk wades into the controversy of the activist’s resignation amid sexual misconduct claims from the Tor Project, a software application he helped develop that allows for greater online anonymity in an age of hyper surveillance.

Poitras’s feelings of being used and disliked by Assange are plainly yet powerfully described as well, complicating scenes of paranoia and charm she glimpses as he blithely defends his vision of a new, more transparent society in which powerful elites are brought to heel by hackers and internet journalists such as himself. The depictions of Assange, often working with his associate Sarah Harrison both before and after he was granted political asylum from Ecuador, remain much the same as they were before. Poitras explains, in voiceover, how her involvement in the Snowden affair put her at odds with Assange, who wanted to control how the revelations were disseminated.

Still, regardless of how her subject views the finished product, the filmmaker is still willing to cast doubt on the veracity of the Swedish accounts and certainly does not buy into the rhetoric that Assange and Wikileaks are working in favor of Russia or Donald Trump. “I can’t verify this but I believe that if Julian had Trump’s tax returns, he would release them,” Poitras told me, flushing a bit as she took on a smile. “I mean, look at Julian. What makes you think he would say, ‘Oh, I’m going to hold that back?’”

The question of whether such a revelation today would make any difference — I hope more than much of the contemporary documentary filmmaking I have spent my adulthood consuming — was one I didn’t ask her. Perhaps I was too scared of the answer.