Back to selection

Back to selection

The Mountain and the Music

Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 24, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Nick Dawson interviewed Beaufort co-writer-director Joseph Cedar for our Web Exclusives section of the Website. Beaufort is nominated for Best Foreign Language Film.

This was a particularly exceptional year for Israeli cinema. Dror Shaul’s Sweet Mud won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize at Sundance; Shira Geffen and Etgar Keret’s Jellyfish took away two prizes, including the coveted Caméra d’Or, at Cannes; and Eytan Fox’s The Bubble played to great acclaim at festivals worldwide before a U.S. theatrical run. But it was two other films, Beaufort and The Band’s Visit, which dominated the headlines. This was initially because Beaufort, Joseph Cedar’s third film as writer-director, won the Silver Bear (for Best Director) at Berlin, and then The Band’s Visit, Eran Kolirin’s feature debut, won the hearts of critics at Cannes and came away with a distribution deal with Sony Pictures Classics. At the Ophirs, Israel’s equivalent of the Oscars, Beaufort and The Band’s Visit dominated the proceedings; they were nominated in 10 and 13 categories respectively. Kolirin’s film won eight awards (including Best Actor, Actress, Director, Screenplay and Film), leaving Beaufort to pick up four awards in the lesser categories.

The success of Kolirin’s crowd-pleasing film was hardly a surprise. Its plot centers on an Egyptian police band who arrive in Israel for a concert, but ends up stuck in a nowhere town with an almost identical name to their chosen destination. Language and culture barriers are overcome as the Arab visitors are taken in by hospitable Jews who run the local café, and Kolirin paints the brief collision of these two worlds with gentle humor and an irresistible, understated charm. Beaufort, on the other hand, grapples more seriously with its questions of political and national coexistence. It takes as its subject the real life story of the withdrawal of Israeli troops in 2000 from Beaufort, the ancient hill fort it captured from Lebanon 18 years previously. An antiwar film in the classic mold, it is an intense, claustrophobic experience that puts the audience in the place of the soldiers evacuating the outpost and makes a subtle but compelling case for the utter futility of war. Arguably more profound and complex, Cedar’s film is simply a harder sell for audiences.

When The Band’s Visit won Best Picture at the Ophirs, it automatically became Israel’s submission for the Best Foreign Language Picture at the Academy Awards. However, it was disqualified by the Academy for having more than 60 precent English dialogue in it — because English is the only language the Israeli and Egyptian characters have in common. Its disqualification became a cause celebre among film journalists who decried the Academy’s decision, but the story took on an even more dramatic angle after it was claimed that the producers of Beaufort, the runner-up at the Ophirs — and thus the replacement Israeli submission — had spoken to the Israeli Academy about the amount of English in Kolirin’s film prior to its disqualification. Though the controversy seemed more like a cooked-up publicity stunt, it did unfortunately cause bad blood between the makers of the two films. The falling out is sadly ironic given that both films concern the pointlessness of conflict, stress the similarities between people regardless of their background, and ultimately show optimism about Israel’s future at a time when peace seems very distant in the Middle East.

As a joint interview with the directors of the two films was a logistical impossibility, Filmmaker sat down with Cedar during a visit to New York City and spoke with Kolirin on the phone in Los Angeles two days later and asked him the same set of questions in an attempt to draw out the similarities and differences between the directors and their works. Beaufort is released on Jan. 18 through Kino and The Band’s Visit on Feb. 18 through Sony Pictures Classics.

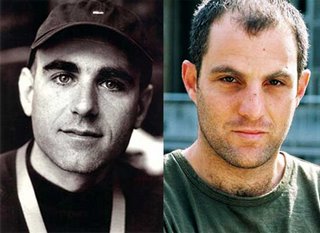

TOP OF PAGE: JOSEPH CEDAR’S BEAUFORT AND ERAN KOLIRIN’S THE BAND’S VISIT. ABOVE (L-R): DIRECTORS CEDAR AND KOLIRIN. BEAUFORT PHOTOS BY KINO. THE BAND’S VISIT PHOTOS BY SONY PICTURES CLASSICS.

TOP OF PAGE: JOSEPH CEDAR’S BEAUFORT AND ERAN KOLIRIN’S THE BAND’S VISIT. ABOVE (L-R): DIRECTORS CEDAR AND KOLIRIN. BEAUFORT PHOTOS BY KINO. THE BAND’S VISIT PHOTOS BY SONY PICTURES CLASSICS.Filmmaker: To what extent is your film political?

Cedar: I think it’s political for the audience. The way it’s perceived has to do with the political context of the time when it came out, the place that it’s from, but it’s not political for me. There’s nothing in the process of making the film that had a political flavor to it. There was never a consideration that overrides an attempt to understand the story and the characters. And if there is something political, it’s mostly there without my awareness. You only realize what that political idea is when the film is finished.

Kolirin: It’s a very political movie for me. I don’t see any straight line that separates the political from the personal. In this way, it’s very personal and also very political. I think the movie addresses political issues which are not the obvious ones that are usually being dealt with: the neglect of Arab culture in Israel, the urge of Israel to be immersed in the West and this urge that exists all over the region for getting itself in the West. It’s about how the modernization process and capitalization process has influenced Israel and the region, partly making people lose their identity in favor of a blurred globalized identity. These are all political questions for me.

Filmmaker: How much has your cultural and ethnic identity affected the way that you make films?

Cedar: Deeply, I think. The only reason I feel authority on set is if I feel more familiar with the material than anyone else, and the only way for me to gain that authority is to really bring things that I’m intimately familiar with. Beaufort is probably the furthest away from my communal background in what I’ve done so far, but it is close to my experiences from the military.

Kolirin: Everything that makes you affects the film. A film, if it’s good, is a kind of mirror of your own very personal and deep self. But it’s not something I can describe to you very simply, like “Because I was born here, this is why… ” It obviously affects [things], but I don’t have the names for the effects. The basis of film and art are very abstract things and they are there to take out things that are abstract. If you could analyze this way, then what is the point of making films?

Filmmaker: To what extent did your personal experiences influence your film?

Cedar: If I look back at my experiences as a young soldier, when I was 18 in Lebanon, I was a different person. I had less self-awareness and, practically, I wasn’t afraid of anything. I was a child and a lot of my actions were not responsible. I made this film as a 38-year-old person who has become a parent in the meantime. Looking back at myself, it gives the film this hindsight that young soldiers don’t have.

Kolirin: Everything I experience transfers into the film. Part of my character goes into the film — the characters are all resemblances of myself. The whole story of Simon who cannot finish his concerto is a reflection that went in the script after I got really stuck writing it for years. It was the same with me as it was with Simon: I accepted the fact that I need not push this story into high dramatic overwhelming peaks and I didn’t have to make anything perfect and big — I should just make something that moves me.

Filmmaker: What were your goals with this movie?

Cedar: Like any film, you want people to see it. But the goals and the challenges are not always the same, I think. Any filmmaker’s goal is to put a story on the screen that people will appreciate. At least while I’m making the film, the goal becomes just to figure out what the story is about and how to get to that. It doesn’t always happen. Sometimes it happens in the editing room, sometimes it happens in an interview with a journalist where you suddenly find out, “Oh, that’s what’s on the screen.”

Kolirin: The goals are very simple and personal. I tried to be truthful when I was shooting. I tried to be truthful when I was writing the story. I tried to find a certain color or tone of the movie that will in some way convey a very vague feeling that I had. People think the creative process begins with a kind of goal that you have, and then you say, “Well, the best way to get this goal is to do a movie about an Egyptian band,” but it’s completely the opposite way around. First you have an Egyptian band, and then you try to understand why [you are thinking about] an Egyptian band. You have some feeling towards this band but you’re not too sure and you try to find it, and in the end of the day there’s a movie and people come and see it. I’m not a politician, I don’t have a goal. I try to make films.

Filmmaker: How important a role can cinema play in helping ease tensions in Israel?

Cedar: Zero. I don’t think that films make a difference at all. I think you can learn a lot about a society by the films that are being made in a country or the films that audiences seem to catch on to but I don’t think any film really has the power to change. It’s more a reflection of what’s going on anyway than something that manipulates reality. Sometimes if you look from a distance at a certain period, you might be able to see a trend or slight movement that has to do with culture in general, but it’s something that you can evaluate only much further down the line.

Kolirin: You know, I was once reading an interview with Ken Loach, a director that I like very much, and they asked him, [because] his films are very socially aware, if he thinks cinema can change the way people think. He said, “Well, I hope it doesn’t!” Because 99 percent of the movies being made are extremely right-wing American Hollywood movies. My movie is not a political act in this sense, and I don’t think it can help do anything. But if it can just help one person who watched to have this elevating feeling that you have sometimes when you walk out of a cinema when you like something, then it’s fine with me.

Filmmaker: Is it possible to make a film in Israel today without it being in some way political?

Cedar: That’s a big question, because even the way Israeli films are perceived outside of Israel, even if they have no political angle to them and they could have taken place anywhere, that in itself turns into a political statement because you’re asking the filmmaker, “How can you ignore the conflict around?” So it’s hard to escape that. My films are connected to things that are going on around, but not all Israeli films [are], that’s for sure.

Kolirin: It’s an academic question because I don’t know if there’s a possibility of doing a movie anywhere in the world without being political. If you disregard the political, then you’re political. If you do political, then you’re political. Israel in the ’90s was the time of the personal cinema that had nothing to do with politics. There were films being made about family, but this whole movement was political because it was saying, “Let’s be personal for a moment.” Anything is political, in a way.

Filmmaker: What is the message of your film?

Cedar: You know, if there was one message that I could articulate in a sentence, then it wouldn’t really have been worth the four or five years working on this film. It’s about a change that happened to me, and other people, over the 18 years Israel spent in Lebanon. It has to do with acknowledging fear, with being willing to swallow your pride and let go of symbols of power — mountains, flags, lands — and somehow find an alternative meaning to yours that doesn’t have to do with military control. That’s a process that happens to the main character in the film, and I think it’s a process that reflects something that Israelis have gone through. So if there is a message, it somehow relates to that idea.

Kolirin: I have no message. [laughs] If I have a message, I write an e-mail. Why would I spend so many years of my life in doing something that has a message that I can say in one word over the phone? It’s ridiculous. It’s about a lot of things for me. It consists of many thoughts and feelings that I have. Sometimes a viewer can go into a film and just take one sentence from it and think that this is the message. This is okay, anyone can do whatever he wants but from my side it consists of many, many things.

Filmmaker: How much of an attempt was made to draw parallels between different factions and to show the futility of conflict?

Cedar: The basic structure of the film, I think, has to do with that. One of the crucial choices that we took was that we were not showing the enemy, we were not showing the larger picture. There’s something very random about the danger that they’re confronted with, it’s almost like a force of nature: it’s inevitable, it’s random, there’s nothing you can do about it, and you definitely can’t beat it. The best you can hope for is to survive it, and that’s what the story is about. It’s about survival, and how fear is a survival tool. Withdrawing from Lebanon was an act of fear, but it resulted in the survival of many people. It’s a pretty good idea to try to just stop war and then wonder what will happen. Even if what happens turns out to be bad, it’s still something that’s worth arguing with. So the futility of any battle is in the genes of the movie.

Kolirin: It was very instinctive and very obvious for me that once you write a film then all your characters should be complete. It’s my own very personal, deep belief that at the end of the day people, when you go to their basic, fundamental elements — and art and drama thrives for the basic, fundamental elements and not for the exterior nuances — they are the same. But it’s not about this movie. There are a lot of differences between the characters, but you can share their pain, their happiness, their feeling of incompleteness. In some way, these feelings are universal, but again it’s not the goal or the starting point of anything showing that this is it.

Filmmaker: Do you feel peace is achievable in Israel? Is the country moving in the right direction?

Cedar: I don’t have an intelligent answer to that. I have a family and we’re playing it by ear just like everybody else, just waiting to see what will happen. Hopefully things will be good, but I don’t have an understanding of the political situation in the Middle East anymore than anyone else. I hope that everyone around me will be safe, and that’s it. You hope that the leadership knows what it’s doing, but as I’m reaching an age that is getting closer to the age of the leaders who are running the countries, I am beginning to understand that there’s no chance that they know what they’re doing. My generation will be running the country in about 15 years, and I think I know some of the people who will be in those positions, and why would they know better than anyone else? They’re just young people who grew up and suddenly find themselves prime ministers and defense ministers and what gives them the knowledge that other people don’t have? I’m not cynical about it, [but] I don’t rely on leaders.

Kolirin: [laughs] No, I don’t think peace is achievable. I think we’re going to all drown holding each other’s throats. [laughs] I think it’s going to be bad, and then it’s going to deteriorate. [laughs] I’m being totally honest — there’s no irony. [laughs] This is the awful sad truth.

Filmmaker: Your film has been sufficiently successful for you to be able to make films elsewhere in the world. Do you feel it is important, however, to continue to making films in Israel?

Cedar: Not necessarily. It’s important to keep making films that matter to me, or matter to someone. The more experience I’m getting, the less I’m feeling that there’s such a thing as national cinema. Most filmmakers I know work in a certain national environment because they live somewhere, and they’re a citizen of some country, but the work itself is detached from that. My next film is a very Jewish film, but it’s not an Israeli film.

Kolirin: It’s a question I’ve been contemplating ever since The Band’s Visit has been successful. I do feel that in some very deep way that I’m very connected, and understand some things in Israel more deeply and I do see the importance — not for the world, [laughs] but for my own soul — to do films in Israel. I don’t have the big answer for this question, but I do think it’s very much my place to do films in Israel.

Filmmaker: What is your opinion of the perceived Beaufort – The Band’s Visit rivalry?

Cedar: There is no rivalry. I feel like we’re the victim of a publicity campaign that has nothing to do with reality. I have nothing against them. If anything, I feel bad that they were disqualified. I really like The Band’s Visit. The first time I saw it, I was really blown away by it. That’s a perfect example of what I was talking about before, a film where you don’t feel the effort [to be potentially successful internationally]: it’s universal and very appealing to audiences outside of Israel, but it’s not something where you can feel there was some kind of manipulative or exploitative intention in it. There is no rivalry. I’m mad at the producers who blamed me for something that I didn’t do — and they should apologize to me — but I have nothing against the film itself.

Kolirin: I don’t know. Whatever started this thing, I have never said anything about it and I have no idea of any kind of rivalry. Joseph Cedar and I are pretty [much] friends and I have no problem with Beaufort, and [I wish it] all the best in the world.

Filmmaker: Do you feel the image of Israeli filmmakers has been damaged by the controversy?

Cedar: I don’t think so. The truth is, I don’t think people really care about this. I hope not. It’s completely artificial: there is no real fight. When I spoke to the producers of The Band’s Visit about this whole thing, none of them really think that there is anyone to blame other than the rules of the Academy for this disqualification. The Israeli Academy is responsible for sending a film to the Oscars and if they send a film that’s disqualified, they can’t submit another one. What my producer did was ask the Israeli Academy to make sure that if a film they sent was disqualified they could send another one. That’s it.

Kolirin: I don’t know. I’m not the one to answer this. [laughs] You know, as a citizen of this world I know that this incident is no more than an anecdote which will be forgotten very, very quickly. [laughs]