Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“Every Change I Make is Then Turned into a Budget and an Invoice”: Editor Mike Sale on Black Adam

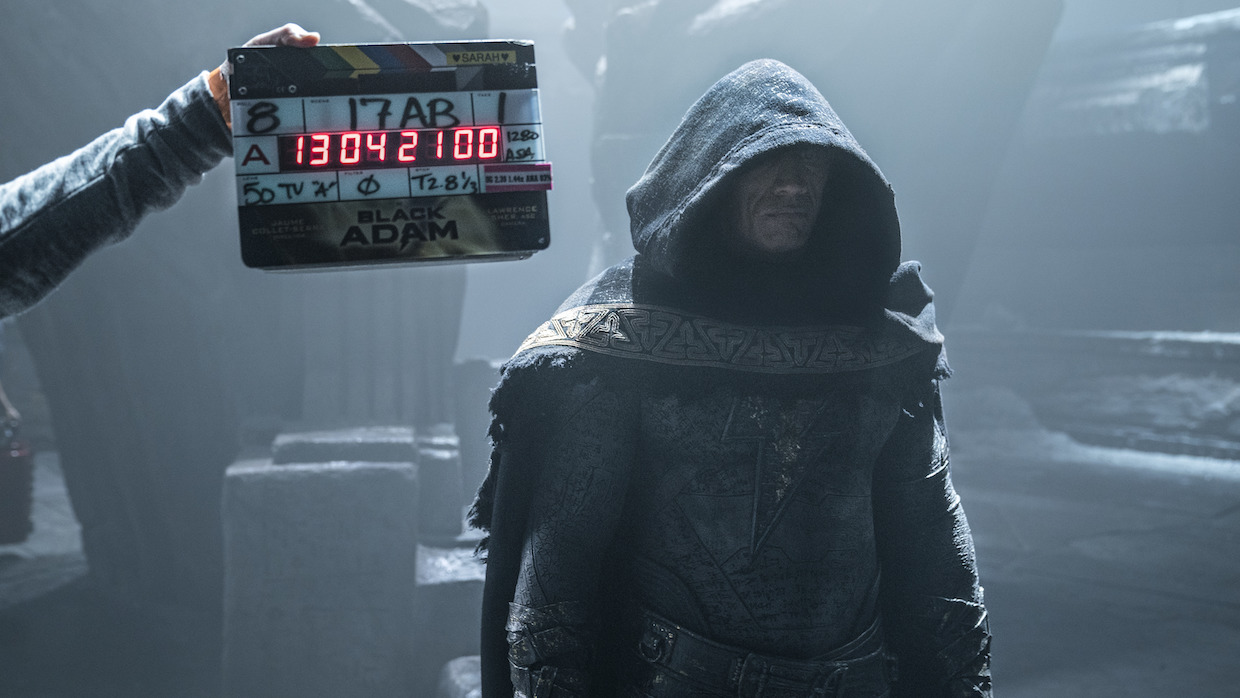

Dwayne Johnson on the set of Black Adam (photo by Frank Masi)

Dwayne Johnson on the set of Black Adam (photo by Frank Masi) Your first feature film credit is a memorable experience for anyone who grew up loving movies, but for editor Mike Sale, ACE, that inaugural gig was particularly indelible. Sale made his cinematic debut on the infamous trading card-to-movie adaptation of The Garbage Pail Kids.

“It was like a film school—the Garbage Pail Kids film school,” laughed Sale. “It was a fascinating learning experience and I had a lot to learn back then. Just seeing that kind of movie come together was incredible for a young person who had never made a movie before.”

Sale graduated from Garbage Pail Kids film school to a distinguished career working on intentionally funny movies, including Bridesmaids and We’re the Millers as well as additional editor credits on Superbad, Forgetting Sarah Marshall and I Love You, Man.

He has also expanded into the world of big budget action spectacle, beginning with 2018’s Skyscraper and most recently on the Dwayne Johnson-fronted adaptation of DC Comics’s Black Adam. With the movie still in theaters and now also out on premium VOD, Sale spoke to Filmmaker about the early days of Avid, the intricacies of the VFX/editorial workflow and how he doesn’t so much finish an edit as “eventually they just make me stop.”

Filmmaker: The first thing I see on your list of IMDB credits is an assistant editor gig on The Garbage Pail Kids Movie. Was that actually your first film job?

Sale: I’m so glad you asked about that. Yes, it was indeed my first feature. It’s considered to be one of the worst films ever made. For a long time I was kind of like, “How do I get rid of this [from my filmography]?” Now I love it. It’s just part of my learning journey, and I learned so much on that. It was a low budget movie, so they let me do everything. I was an assistant editor, but I went and helped cut the negative. It’s the movie that got me in the union. Let me show something. You’ll love this. [Sale picks up a box of Garbage Pail Kids trading cards from his desk and holds it up to his webcam.] I’ve still got the cards.

I had to actually take the film to Maine by myself. I flew into Logan Airport in Boston, rented a car, drove up to Maine and did a preview. The preview company was there, but I was the only person from the filmmaking team. I was like 22. It was the first time I ever went to a preview. It was back in the payphone days, and after the screening I used the payphone in the lobby to call one of the producers, who asked, “How are the kids reacting?” The screening was a bunch of six-year-olds, and I was like, “I don’t know. They’re screaming and running around.” And the producer goes, “I guess that’s good.” [laughs]

It was also interesting technically, because it was one of the first feature films that was cut electronically. It was a system called the Ediflex and we actually cut it on video. There’s a mathematical conundrum between videotape and film. Film was 24 frames a second and videotape was 30. When you transfer film onto videotape, you’re making a certain number of frames that are just an amalgam of two film frames that don’t really exist on the film, right? If you are then working on that machine and you make a cut, how do you know if you’re cutting a real frame [or you’re cutting one of these frames that is an amalgamation]? The answer is, if you start every take at a zero time code and you then transfer it even, then time code numbers that end in a one and a six are going to be fake. They’re not going to be real frames. When we were done cutting, I would literally sit there with a list of the time code numbers and highlight all the ones that ended on a one and a six and the editor would go in and adjust the cut.

The first editing system that I had that was truly at 24 frames was the Avid, and that was one of the reasons why Avid came in so strong, because it basically would undo what’s called the 3:2 pull down when you combine those frames. It would essentially only digitize the frames that were real. It wouldn’t digitize the ones and the sixes. So, the frames you had in the Avid were identical to what was on your negative.

Filmmaker: What were the difficulties of working with the early versions of the Avid?

Sale: The problem with the early Avid was how much storage you could put online at one time. When I first started working on [the late 1980s drama series] L.A. Law, we had six two-gigabyte drives—so, 12 gigs total. They were crazy expensive and looked like shoe boxes. That could hold the dailies for about one act of L.A. Law, like one ten-minute chunk. Then you had to shut down the whole machine, spin down the drives and manually pull them out. We had special bookshelves for these drives made where you could sit them in there, because you needed tons of them to do multiple episodes. Then we’d reload the next set of six drives, spin them up and it would take about 20 minutes to switch over. Then you would go to your next reel and cut. It was somewhere around maybe 1995 or 1996 when Avid came out with these giant towers on wheels, and then you could have three towers that were like 180 gigs, I think. Once you got to that, you could have the whole movie online [at once]. I think it was a movie called My Fellow Americans (1996) that was the first one where we were actually able to play the whole movie from beginning to end for the director in the cutting room. But to do it, we had to build it, then close all the other bins, quit the application, restart it, and cross our fingers that it was going to make it through the whole two-hour length of the movie.

Filmmaker: Are you still on Avid?

Sale: I’ve cut on other things, but we’re still mainly cutting on Avid. The projects I work on have many people working together, and no one has really been able to approach Avid’s level of networking and also the accountability of their network. The thing is that Avid makes the editing machines and the network. A lot of the other products just make the editing software. So, if your network suddenly doesn’t work and you call the network people, they might say, “Well, maybe it’s the [software].” With Avid, it’s only one person [for the software and the network]. I think that’s the biggest thing that gives them an advantage. But at home I have Adobe and I have Final Cut, and if I do little projects—which I rarely do, because I don’t usually want to do extra editing [laughs]—I’ve done them on the other softwares. I love to experiment and play with new software.

Filmmaker: When you’re working on a movie the size of Black Adam, it’s not unusual to have multiple editors. On the film you share credit with John Lee. How did you divide up the work?

Sale: For this specific movie—and this was always planned from the beginning—John Lee started as the editor because I was finishing another movie called Red Notice. So, I was not available when this movie started shooting. In fact, I wasn’t available until shooting was completed. John has a really extensive comic book movie background [Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, Suicide Squad, X-Men: Dark Phoenix], so having him on board during shooting was great. Since I came on late, I started out at reel one and just kind of did a pass all the way through the reels, where I learned and looked at the footage, cut some stuff and made some alts. Once we all were on equal footing, we all worked on it together. By the time the movie was done, we had both worked on all of the scenes.

Filmmaker: When you heard they were pushing the release date, was your reaction, “Thank god, I need more time to finish this”?

Sale: I’m always happy to have extra time because I know that the more time we can spend on something, the better we can make it. I never really feel like I finish a movie. Eventually they just make me stop.

Filmmaker: How is your job different on a $200 million comic book movie compared to a $40 million comedy?

Sale: The difference is massive. On a little comedy, it’s a much more intimate thing. You have the director, you might have a couple of picture assistants and maybe you have one or two editors—though often it’s just one. It’s a much smaller group of people and you don’t have all these visual effects shots, so you pretty much have all the material [when you start editing in post]. When you get into these big visual effects movies, whether it be like Skyscraper or Black Adam, in addition to multiple editors, you have way more assistants, because you’re dealing with a lot of material coming in and out of the system. You’re sending stuff to visual effects, they’re sending stuff to you and that happens over and over, version after version. You have a large team. You’re often in the same building as the visual effects team, which may have 20 or 30 people, and a lot of those people are hooked up to your Avids. Basically, every change I make is then turned into a budget and an invoice. We have entire reels where every shot has a visual effect, so every single edit, trim, extension or shuffle has a ripple effect that can cost a lot of money. I could drop in a shot that could be a $150,000 shot that’s three seconds long. Many, many times I would bring the visual effects supervisor into my room, and it’d be like, “If I do this, what’s going to happen?” And sometimes he would go, “Oh, that’s not a problem.” And sometimes he would be like, “Oh no!” Some of it on Black Adam wasn’t even about cost. It was more about how much visual effects work could the vendors accomplish before our release date. Whereas when we’re cutting a comedy like Bridesmaids, I have nine hours of footage and none of them have visual effects. I can go in there and make 400 versions of a scene, then we can pick which one we want.

Filmmaker: I imagine it’s difficult to get a VFX-heavy scene cut together without effects in there, but at the same time the VFX vendors need your edits to have some idea of what scenes and shots will ultimately make the final cut, so you don’t end up wasting time and money creating effects that aren’t in the movie. How do you deal with that conundrum?

Sale: Oh man, it’s really hard. The cool thing is the visual effects team and the studio do everything they can to provide you with everything that you want. People sometimes think there are these overlords saying “no,” but it’s actually the opposite. People are working very hard to make the best movie. If that means more shots, more time or more budget, people work really hard to try to do that. Obviously, you don’t want to waste money. One of the things that happens is you’re not pulling the trigger on all the shots [that might be in the previs] until you know that they’re in the movie. If you have a big sequence with 200 visual effects shots, like a fight sequence, [the VFX team] might take 40 thoughtful shots and start working on them—maybe one shot of this character, one of that character, one that shows this part of the world. After you say, “OK, all of this is going to be in the movie,” they iterate the other 160 shots or whatever it is that’s left in the scene. Early on sometimes they’ll come to me and go, “Mike, is this scene like a slam dunk scene or is this a scene that you’re going to make a lot of versions of?”

And if I’m like, “I think this one’s a lot of versions,” they’ll go, “OK, we’re going to make one or two of those shots for now” and then we all wait. What happens at the end is all of a sudden you’re getting all these shots. By that point, we’re already in the DI and already doing final mix too. So, we’ve got to go in and open up our picture, patch the sound and redo the score as these effects shots are being dropped in late, because we’ve pushed and pushed those shots in order to maximize our spend so that all the VFX work that is done ends up in the movie. It creates a lot of work and a lot of managerial communication between the departments, and picture editorial is kind of in the middle of all of it.

Filmmaker: Do you get handles on either end of a VFX shot so you don’t start to edit them into a scene and realize, “Damn, I need another four frames of Hawkman landing and rolling to make this cut work”?

Sale: Typically, there’s a standard handle of eight or 16 frames, but there are shots where the director will go, “Give me a little more on the end of that one,” or “I need a little more at the beginning of the this one.” It is true that at the end when the [effects] shots come in, a lot of times we’re opening up a little bit, which is much harder to do than subtracting when you are already in the mix and the DI. Adding is difficult, but that is a lot of times what happens. The battle is to try to not trim or remove shots too early in the process when you don’t have the effects yet, because you have to have faith in the [VFX] artists that maybe they’re going to make something incredible that you won’t want to cut off of. With the fight scenes, matching always gets tricky too. You will have the previs, but when you get the shot maybe a character’s hand is in a slightly different place. The last three or four weeks of the movie. I was working until 10 or 11 at night, just editing by frames all these hundreds and thousands of visual effect shots that were coming in.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the challenges of Black Adam’s prologue. You’ve got a lot of exposition to get in, but you also don’t want to wait too long until we get into the modern-day story with our main characters.

Sale: It’s always a tricky thing on any movie. If you think about the first 20 or 30 minutes of a movie, you’re introducing characters and telling story and exposition all at the same time, and you want to attempt to do it in an entertaining way. In this particular movie, it’s even harder because we basically have to do that twice, because we have Black Adam and then we also have the [Justice Society of America]. What we wanted to do is make Black Adam’s backstory intimate, and ultimately he tells a lot of that backstory to Hawkman personally [later in the film]. The opening [exposition] was just about giving the audience enough to know that world so that it made sense when we did the flashbacks later. We also wanted to talk about the crown, because that’s the MacGuffin that goes through the whole movie. We wanted to make sure that the audience knew the importance of that and mainly we wanted to establish the father/son beats.

[Editor’s note: the following exchange contains spoilers.]

Filmmaker: The mid-credits sequence has become a staple of the superhero film. My son is eight and has grown up with that convention—he calls them “secret endings”—to the point that when we watch something from the 1980s like Back to the Future, he’ll watch the entirety of the credits in case there’s a “secret ending.” What’s the formula behind picking the right moment to place a mid-credits sequence?

Sale: We had our main credits right after the movie. They call it “Main on Ends,” and that was about three minutes. We were like, “That feels like a really good place to do it, emotionally.” It seemed far enough away from the end of the movie, because you don’t want to rob that. You want to get far away enough so that your emotion sort of resets, and you can start brand new. Putting it in the middle or the end of the actual crawl probably would’ve just been too far away. So, it seemed like a good place.

As a kid who used to clean movie theaters in 1978 when the Christopher Reeve Superman came out, listening to the John Williams theme post-matinee made you feel like a million dollars even though you were sweeping popcorn off of the ground. When I was in my editing room and the Black Adam mid-credits footage came in, I couldn’t believe it. I was like, “Oh my God, I might be working on a movie that Superman is going to be in!” It was a wonderful, emotional experience for me, and to see the audience reactions to that scene has been awesome.