Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation: Call To Arms

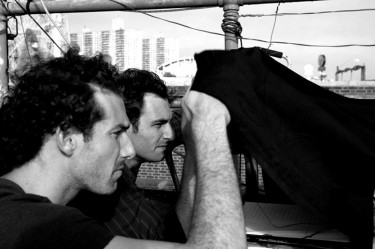

Our last few posts have really sparked a great conversation and it seems to be one of definition. Not just of micro’s structure, but definition of our stance on art vs. commerce, and our perspective of micro’s purpose. A while back I made a half-joke on this column that someone should write a manifesto for micro-budget filmmakers. The more I thought about what it would contain, the more I realized I was writing one of my own. I immediately contacted one of our column alums Jamie Heinrich. Jamie is in the process of financing and shooting his next feature via Kickstarter and it seemed like a perfect fit to try and come up with something together. (More on that later) But…while working on this idea I got an out-of-the-blue answer to my challenge by another group of filmmakers, brothers actually. Paul and Dan Cantagallo are micro-budget filmmakers out of Philly and they came up with a manifesto quite similar to mine, yet at the same time, completely different. We all truly have a different viewpoint of micro, yet there are aspects I hope we can eventually all agree upon. It’s my feeling that if we DON’T come up with some common ground, then who we are will be defined by others. This has happened time and time again, the most recent example; mumblecore. So, for the manifesto post I will present TWO posts. One will be the Cantagallo Brothers (pictured below) poetic call to arms, and the other a study in perspective. I hope both of them stir up feedback, disgust, motivation, rage, excitement, and hopefully a few responses in manifesto form. It is clear that this is not something that just one perspective can cover. This will be a group effort.

Manifesto: Toward a Fugitive Cinema by Paul & Dan Cantagallo

“You must have the courage to be bad — to be willing to risk everything to really express it all.”

— John Cassavetes

“I think our purpose as filmmakers or as storytellers or whatever you’re going to call us is to say that at this particular point with this relationship, with this social structure, in this political climate, this is the best film I could do. Then it becomes extremely personal, for better or worse. So don’t get confused by digital or non-digital or money or not — just do the best fucking film you can with your abilities at that time.”

— Chris Doyle

Friends, make no mistake about it, we are on the run. The American cinema of today has become a prison. Industrialized, regimented, antiseptic, restrained. Ever-watchful, movies today are shot from dozens of cameras and cover multiple tones and angles just in case. And if that’s not enough, well, there’s CGI. Today’s movies, like today’s reality TV, film everything at once. The dreaded Panopticon has finally arrived, and it’s every bit as banal as you’d expect.The thrilling singularity and immediacy of “one camera, one moment” has been utterly erased. The human component of filmmaking — and humanist filmmaking in general — has ironically disappeared under all this contrivance and scrutiny. We watch ourselves so often and in so many ways, we’ve gone blind to that fact that images can be as personal as a lover’s kiss.

We’re digging our way out with a spoon if we have to. Scaling the walls. We’re the fugitives of a dehumanizing moviemaking system. We say forget your superheroes, Hollywood, you can have them. Superheroes with a dark side. Superheroes with drinking problems. Superheroes struggling with arrested development. Look, now — women, even little girls, can be superheroes, too… Cover those demographics. Enough. And then there’s the indies. They practice a kind of miserablism that’s the opposite number of Hollywood chest-thumping. Slaves to The Real, they shove loserdom in our faces and make us feel so bad. So guilty. Why? Because we’re not better people…? Not superheroes…? We smell an agenda here, a ressentiment. That languid, tentative, detached style belies a prudish approach to life. They claim to be showing us Real People and Real Life (ugh). But their dogged allegiance to naturalism as a cinematic attitude is just as dishonest as MTV. That’s not Real Life you’re capturing, citizens! It’s a way of signaling a worthy attempt at capturing Real Life, by disturbing it as little as possible. Shake it up, man! If Hollywood wants to drop us into an iron bodysuit and send us hurtling off into the ether inside a Transformer, the indies wish we’d wear that tired old plaid shirt with pride and just mellow out.

We’re breaking out! Running like hell. Fugitive filmmakers embrace ephemera. The here and now. Remember what that looked like…? When movies captured a time and a place and how people really were…? How Italy felt after the war, what Paris was like in the ’60s, New York in the ’70s…? We don’t have a lot of time or a lot of money. But we’ve got heart, boy — we’ve got it in spades. We celebrate our mysteries in secret. We may be small, but we’re crazed with the enthusiasm of poetic truth. Fugitive filmmaking is not just a description of the scope of a certain tendency in film (micro). It’s an attitude toward the cinematic art form itself and toward Reality. We may be fugitives by choice or necessity. Either way, we tend to fashion our films for a song. Outlaws, we rob the banks of lived experience, and share the take with our fellow cinephiles and moviegoers. Let’s be very clear. It’s not the miniscule size of our budgets or cheap technology or an underdog mentality that makes this a movement. That new camera we bought with our life-savings may hit well above its weight-class, but it’s just a black box without a new vision blazing through its viewfinder. It’s not the family-sized crew or the DIY rigs that make this a movement. It’s, paradoxically, the short-lived freedom that being a fugitive bestows. The freedom, and what we do with it. When you’re a fugitive, there’s no studio (maybe even no producer) looking over your shoulder. Between you and the shimmering chaos of Reality there’s nothing but your camera and your personal vision. We strive for honest forms of self-expression and discovering The New, which can never be anticipated or defined by the marketplace. What makes movies move us has always been just that: we can’t see and know everything. That, like us, Reality remains elusive. Cinema still has the power to tell us what it feels like in a particular place at a particular time through a sequence of magnificent images. We need to put our faith back into movies, back into the cinema. Unlike with Hollywood, indies, reality TV, and YouTube, at the heart of the fugitive style of filmmaking is a human voice crying out for freedom.

- Let your aesthetics do the talking.

- Do not mumble when you can whisper. Do not whisper when you can shout.

- It’s just as valid to revere Reality as slap it in the face.

- Seek ecstasy in the churning pit of life. Assume the voices, tones, and colors of your environment.

- Do not be a slave to technology. Be a master of vision.

- Accept the tango with chance. Film in and for the moment only.

- Always be drunk and stay that way.

- Do not fear vulgarity. Destroy the image. Discover the unfamiliar.

- One camera, one truck, all heart.

- Work only with other fugitives.

— Paul and Dan Cantagallo

Stay tuned for Part 2 where Jamie Heinrich and I discuss perspective in the process of manifesto writing.

braveandthekind@gmail.com