Back to selection

Back to selection

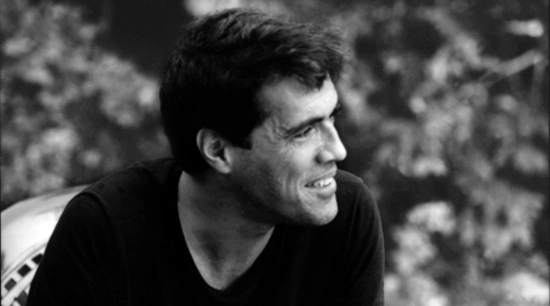

James Lyons, 1960 – 2007

James Lyons

James Lyons Jim Lyons died on Thursday in New York.

If you didn’t know Jim personally and just recognize his name from movie credits, then you most probably remember him as an editor. His credits include four films by Todd Haynes – Poison, Safe, Velvet Goldmine and Far from Heaven – as well as Spring Forward, The Virgin Suicides, and Silver Lake Life. Most recently, he was the co-editor of A Walk into the Sea: The Danny Williams Story. The latter, a documentary by Esther Robinson about her uncle’s relationship with Andy Warhol and The Factory, won the Teddy at Berlin this year and receives its U.S. premiere at Tribeca this month. He was also an AIDS activist and educator.

But Jim did many other things – he wrote, acted and had plans to direct – and his great contribution to our world of film lay in his contributions not to any one of these fields but rather across them. Jim was an artist, even when he was editing someone else’s material, and he brought an artist’s sensibility, temperament and questioning to everything he did. Whether it was playing the artist David Wojnarowicz in Steve McLean’s Postcards from America or Billy Name in Mary Harron’s I Shot Andy Warhol, or co-writing the story for Velvet Goldmine, Jim’s work questioned the social codes and roles that act to define us while also finding the elements of beauty in the spaces in between.

A few years ago ran a piece in which we asked people to tell us what was inspiring them in their work. Jim’s response, excerpted below, is a good illustration of the range and passion of his interests:

“Punk rock and Michel Foucault. I’m writing a script about Foucault’s life and how it intersected with the San Francisco underground sex and music scenes of the early ‘80s while he was teaching at Berkeley. Foucault insisted that philosophical ideas had real-life consequences, something I rarely see addressed in independent movies. He wrote about power and how its best trick was to make itself seem normal and inevitable. He believed that new pleasures and identities and ways of living were always possible because freedom was there for the taking. Unfortunately, they came together during Reagan’s ‘80s, which was the beginning of the national nightmare we are living today.”

I worked with Jim twice – he cut two films Robin O’Hara and I produced, First Love, Last Rites, and The Chateau, both directed by Jesse Peretz. Before I hired him on the first one, I called another producer who had worked with him. He told me not to expect a facile technician who would whip out 20 different versions of a scene on the Avid in an afternoon. “What you have to understand about working with Jim,” he told me, “is that sometimes he’ll need to leave the editing room in the afternoon for an hour and walk around the block a few times. But when he comes back, he’ll come back with a great idea that will really improve the movie.”

In the end, that’s what I’ll remember most about working with Jim: his passion for the world of ideas. He was always about discovering the meanings that could be teased out of a cut, a shot, an ordering of scenes or an inflection in an actor’s line of dialogue. I think Jim gave me the best understanding of the goals of editing when he paraphrased one day Roland Barthes’ S/Z. “Editing,” he said, “is all about when and how you ask the question and when and how you answer it.” Elsewhere, he talked about his admiration of Yasujiro Ozu and his belief in the power of silence in cinema (“The less you say in film the better,” Jim wrote) and cited Virginia Woolf as an inspiration on his work. Her writing showed, he felt, that “moments of being could embody whole lives if looked at closely and honestly enough.”

In the last couple of years Jim slowed down his work editing other people’s movies and started to plan his own projects. He was going to make a short he had received funding for from the Creative Capital Foundation. It was titled A Short Film about Andy Warhol, and, if I remember correctly, would take the viewer between two moments, one with Warhol at a Factory party and the other, an interior moment with Warhol alone in a taxi on the way home from a social engagement. In its two glimpses, the film depicted Warhol as an icon and as a person, recognizing his status as the former while wondering what it was like for him as the latter. In his grant application, Lyons hoped the project would be “experimental in both film and subject matter, political in intent, poetic in effect.” I thought it was a lovely script and I couldn’t wait to see what Jim was going to do with it. That film, the Foucault/punk rock movie, and, most importantly, his overriding intelligence, personal sensitivity and sense of engagement… Our world is diminished now that Jim and his work are no longer a part of it.

His familly is requesting that, in lieu of flowers, donations to the James K. Lyons Memorial Fund, 47 Davis Road, Port Washington, NY 11050, would be gratefully appreciated.