Back to selection

Back to selection

Wim Wenders, Pina

German filmmaker Wim Wenders started taking photographs at the age of seven. Over the years he has turned his attentions to medicine, philosophy, painting, and engraving, but it is his four decades directing that has most often caught the publics’ attention. I first saw and loved his films with Wings of Desire; later I could be found carrying around a copy of his book Once religiously.

German filmmaker Wim Wenders started taking photographs at the age of seven. Over the years he has turned his attentions to medicine, philosophy, painting, and engraving, but it is his four decades directing that has most often caught the publics’ attention. I first saw and loved his films with Wings of Desire; later I could be found carrying around a copy of his book Once religiously.

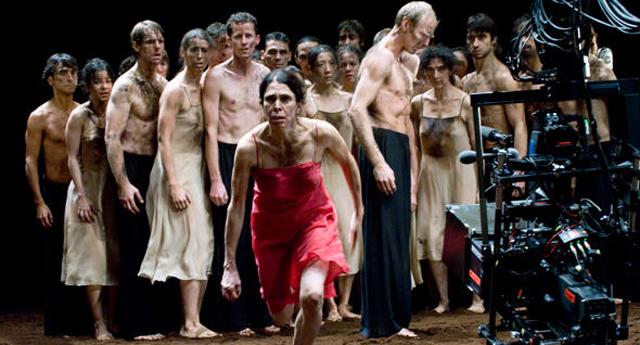

His new film Pina, is a loving tribute to his 20-year friendship with, and admiration of, the dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch. It is a documentary that uses new 3D technology to exquisite effect. As he relates below, Wenders first approached Bausch about making a film together after being moved to tears by her dance performance, Café Müller. She agreed, but it then took him those two decades, and the advances in 3D technology, before he felt he could do justice on film to her work. The resulting film is a beautiful film/dance journey that explores love, life, and loss – and without words, represents the friendship of two great artists.

Wenders:Where are you calling me from?

Filmmaker: New York City. Where are you?

Wenders: I’m in Hamburg Germany. I hope your weather is not as bad as it is out here. It’s so nasty here, I’m sneezing, I’ve been shooting all week with my students in the freezing rain. We were looking for a week of sunshine and instead we had a week of hail and snow and rain. I think we got some good stuff but I am just looking forward to being indoors again.

Filmmaker: Are you sick of talking to people yet about Pina?

Wenders: No, no no – it’s nice to speak about Pina. I have not done any talking for the last few days in that context. I look at interviews the way I look at filmmaking and try to follow the advice that I give my actors: do it like it’s the first time. I think the only way to do an interview is to forget that you ever answered the question before. And then before you know it, there is a question that no one has ever asked you before.

Filmmaker: Wonderful, then let’s talk about Pina. I am interested in work that addresses non-verbal communication and obviously, Pina Bausch’s work as a choreographer deals with this. But I feel that your work also deals with non-verbal communication. Could you tell me how you came to be friends and collaborators?

Wenders: I must admit that I didn’t have much to do with dance. I had a prejudice. Ballet was certainly a very aesthetic experience and people had a taste for it, but I didn’t have the taste for it. I didn’t know much about dance and didn’t know anything about Pina Bausch. Twenty-five years ago my girlfriend decided to take me to a double bill of two pieces by Pina Bausch. I resisted. I said no. I didn’t expect much and thought there were greater ways to spend an evening in Venice, Italy. But I caved in and went along ready to have a boring evening, and then the very opposite happened. Something hit me like lightning and I sat there on the edge of my seat from the beginning. I found myself weeping like a baby, weeping through the entire piece, Café Müller, not knowing what was happening to me. I was completely unprepared for the language that Pina showed me that night. Nothing had prepared me. Nothing. I was overwhelmed and emotionally charged like never before. My brain didn’t know what was happening. My body seemed to understand much better. I mean, it was a shock, because in 38 minutes — and that’s as long as Café Müller lasts — this (for me) unknown woman, Pina Bausch, had shown me more about man and woman than the entire history of cinema. Without a single word — just with these sleepwalkers on stage. I had felt and seen and sensed things about men and women that I couldn’t really put my finger on, but what she did I felt is essential and mind-blowing. I didn’t know how she had done it. That was my introduction to dance theater and to Pina Bausch. I don’t think any other night in my life has changed me so much like that night.

Filmmaker: Did you then approach her immediately?

Wenders: I had the luck that the night when I saw Café Müller, and then Le Sacre Du Printemps, was the first night of a retrospective of her work, and I prolonged my stay in Venice and I saw each and every piece, and on the second day I was able to meet Pina for coffee at the coffee shop next to the theater. We had a ten-minute conversation. Pina smoked about three cigarettes and didn’t say anything. I had to babble on because in my juvenile enthusiasm I just had to keep talking. She was very mysterious and silent and had these great beautiful eyes that saw right through me like I was an open book, and didn’t say a word. And that was impressive.

Filmmaker: What did you say to her in your babbling and her silence?

Wenders: Because I just had to keep talking, it just came out of my mouth, I said “Pina, one day the two of us have to make a film together.” And I thought that would get some reaction, but she just lit another cigarette and looked at me. So, I changed the subject and talked about something else. But the next time we met, which was a year later, she saw me, came to me, and said, “Wim, last time we spoke, you mentioned a movie, I’ve thought about it. I think that’s a good idea.” As if it had been the day before.

Filmmaker: And then you spent 20 years thinking about how it is that you could represent her dance on film?

Wenders: Yes, in vain. I mean I tortured my brain because Pina then took it more and more seriously, and then she pushed for it and I sat there at a loss because the more I thought about how I could do this – I mean I wanted to do this very, very much, but when you want to do something on film, you have to have a clue, and I realized I did not know how to film her work. The more I saw it, the more I sat there and looked at it, the less I knew how I could capture this, and what my cameras could do. I just realized that whatever I could put on the screen was a far cry away from what I experienced. I had to admit that to her. I didn’t want to disappoint her. I had to tell her, “Pina, I don’t know how to do it. It’s like an invisible wall separating your work from what I can do with it. And I can’t break through the wall.” Pina knew about that wall, she had experienced it. She just said, “Well, you have to think harder then. One day I’m sure you will find it. There’s got to be a way to film.” She had patience with me. She had patience that lasted 20 years. It became like a running gag. Each time we saw each other she would look at me, and I knew the question was on the table: “Do you know now?” And I had to shrug my shoulders and say, “I still don’t know, Pina.” She said, “Well, it’ll come to you.” I really thought I had to find it in my soul and in my cinematic experience or whatever imagination I had to find a way to do something with dance. I admit that I saw each and every dance film ever made. I realized that the problem had always been on the table. There was something that didn’t work between film and dance. Something was always missing. And even more so with Pina because her dance is so existential, and I couldn’t find it in myself. Then there was the arrival of a whole new technology one day, and that technology did the trick. That technology had tools for filmmakers that could approach movement in a whole different way.

Filmmaker: And you are talking about the 3D technology?

Wenders: Yes. I saw my first 3D film in 2007, and I looked at it and I almost didn’t see the film. I really looked straight through the screen. The only thing in my mind was: That’s what we’ve been missing. That’s what we’ve been looking for. That language was the answer. Because the technology was there the film was possible. It’s not like many filmmakers today who have the technology and then apply it — for us it was the solution. I was really lucky, I must say, because I think I just fell on a subject that had this affinity to the technology. A lot of people who are making movies in 3D, with the glorious exception of Avatar, have really not used it as a new language but as an additional attraction. It is so much more than just an additional attraction. It is truly a new medium. I was lucky that that was exactly the medium that I needed. The only drawback was that it had a hard time dealing with fast moments. It was for depth and for space and width but it wasn’t good with movement. Movement was jerky. We really, really worked hard on finding solutions for that. I wanted to shoot 50 frames per second. It would have been the ideal solution. When we did all these tests we did shoot tests in 50 frames, but projectors all over the world can’t handle anything above 24 frames. We really worked hard to find solutions for that.

Filmmaker: After discussing the film for 20 years and finding the solution for how to shoot it, you lost your friend and collaborator shortly before filming, when Pina died unexpectedly.

Wenders: It was two days before Pina would have seen us shoot, on her stage, the last and conclusive test, for one whole week, with her dancers. Pina had never seen 3D. She only knew my enthusiastic vision of it, or my wishful thinking, if you can say. When we were finally far enough with the technology, and had enough experience that we could show it to her, she would have seen everything on a huge screen live. She always refused to see any of our tests. She met my stereographer [Alain Derobe] and we talked about it. She knew a lot about it in theory, but she’d never seen anything because she’d always said, “Let me just see my own dancers.” When we were finally ready and the trucks were loaded to come show Pina – she left us. Then I cancelled the film. Just pulled the plug. It just seemed completely obsolete. It was out of the question that I would continue without her/ I just dropped the idea and announced to everybody that it was over.

Filmmaker: When or how did you change your mind?

Filmmaker: When or how did you change your mind?

Wenders: My mind was changed by the dancers. It was the dancers who had continued to perform. They had elected an artistic director from their own midst and were fulfilling all the contracts. Two months after Pina died they actually started to rehearse the pieces that Pina and I had selected for the film. That’s when they told me “We’re rehearsing them, and we feel that Pina is still in these, and who knows what can happen? It might be the last time we are doing this. You know how much Pina wanted to shoot this with you, how eager she was to see this new language that you told her about, so we really think you should reconsider your decision. We really think you should film. That’s what Pina would have wanted.” And I realized that they were right. I realized that the decision to cancel the film had been wrong. Not in the sense of our 20 years, but I realized that the film was maybe even more potent for the dancers than for Pina, or her homage, because they really needed a way to deal with that loss. They were performing and they continued performing but they felt there was this huge hole and they had no outlet for it. They needed to say goodbye and they needed to say thank you, and me too. Together maybe, by doing this, that was a way to do so. And then we really decided to go for it, to start a film that would definitely be very different than the film that we had planned before.

Filmmaker: What kinds of changes did you make to your approach?

Wenders: It’s kind of hard to remember because we didn’t do that movie, but it was a film where Pina would have been by my side, and Pina would have been in front of the camera. We would have gone with her to South America on tour, and to Asia, and we would have observed a lot of rehearsals. We would have shot the four pieces that are now the backbone of the film, but we would have shot them with Pina doing critiques and corrections. The dancers never performed without Pina present. The next morning for the entire morning, four or five hours, she would go through the piece second by second almost, and would go through everything that she had seen that she felt was truthful to the initial performance. That was an exciting process to watch, and she would have allowed me to watch that. And she would have been in front of the camera on the journey that we would have done with her and the company. From my point of view, the film would have been trying to film Pina’s eyes at work. Her eyes had been so amazing, so much more able to decipher body language than any person I ever met. Pina had concentrated her entire capacity on her eyes and on seeing body language so precisely with so much differentiation, putting what she saw into these pieces. My interest in the film was to film her eyes at work. Of course, when she was gone, that was no longer possible. Except that I realized, I could, with the dancers. The dancers could, in a way, answer my questions about how Pina saw; how she was able to see the best in each of them. So the body of the film became my questions to the dancers and their way of responding – not verbally – in fact that was out of the question – but with their bodies and with the work that they’d done together with Pina.

Filmmaker: How have the dancers responded to the film?

?Wenders: The artistic director and Pina’s longtime assistant, Robert, they were the first to see it. They saw all the stages of the editing, because they really advised me on the dancing part. If we had done several takes, sometimes I didn’t feel so much difference, but they would see differences and would teach me about seeing differences. In terms of the dancing I very much relied on the dancers and their eyes. When we finally saw the film together for the first time it was a very emotional thing because it was by then a year-and-a-half after Pina had died, and for some of them the first time they heard Pina’s voice again or had seen her image. It was a very, very emotional thing to show the film to them, for them to see themselves – and also there was nobody else present. It was after the dancers had seen it and were happy with it and felt that the film really represented the year we had spent together – that’s when the film, for me, was really finished.

Filmmaker: You have a history of collaborating and of moving from documentary to narrative films. I’m interested in your feelings about how you approach narrative film differently, or the same, as a documentary film?

Wenders: As I get older I feel more and more like the borders are disappearing between narrative cinema and documentary. Sometimes you think you are making a documentary and you’re really telling a story. Like Buena Vista Social Club, I seriously thought I was making a music documentary while we were shooting it. We were shooting in Havana and Amsterdam and New York, and over almost half a year in different places, I was convinced I was making a music documentary. And then I sat down in the edit room and I slowly started to shape the film and then I realized it was a fairy tale. These guys who were shining shoes in the beginning when we met them and then were with the Beatles at Carnegie Hall. That was an amazing story. You think you’re making a documentary but there is a story unraveling out of it. At least I felt like I was involved in the realm of fiction when I was in the edit room much as I was thinking I was doing a documentary when I was shooting it. Shooting Pina – as much as the approach of the film was really documentary, to show something as good as you can show it because you like it and you want to share it with other people is a documentary approach – but what we were shooting, choreography, is in itself, fiction. It is narrative, so it is a strange mixture of a documentary that had as its subject a narrative element. I have a hard time separating them. In my fiction films I sometimes find myself really caring a lot for all the documentary elements — how the city looks in the film and how all these things that you cannot really stage, the clouds, the water, animals and kids, these things that escape control – and how they are represented. Sometimes that is of more importance to me than the story itself. I think I’m a director who is by my nature interested very much in what is there. I really like what is there. I must say I’m much more drawn to documentary and reality-driven films than ever before.

Filmmaker: You also work as a photographer and have published books. Do you feel that there is a similar blurring between the different art forms? Do you make decisions intuitively?

Wenders: I think so, especially as a photographer. I don’t think of myself as a highly technical photographer. I don’t have an assistant. I work on analog film, I shoot strictly out of my hand, with no tripod. I do these journeys on my own, just to take pictures. The pictures I take are really from the guts. It’s an emotional connection to a place. My photography is strictly about place, not so much about people, because movies always deal with people, and even if you like a place and you really want to put the place in the foreground of this story, as soon as the first actor enters, they take center stage and the place always modestly disappears into the background. With photography I can live my love of places more than in movies. Some people think I am sort of an intellectual filmmaker, but nothing could be more wrong.