Back to selection

Back to selection

RELEASED

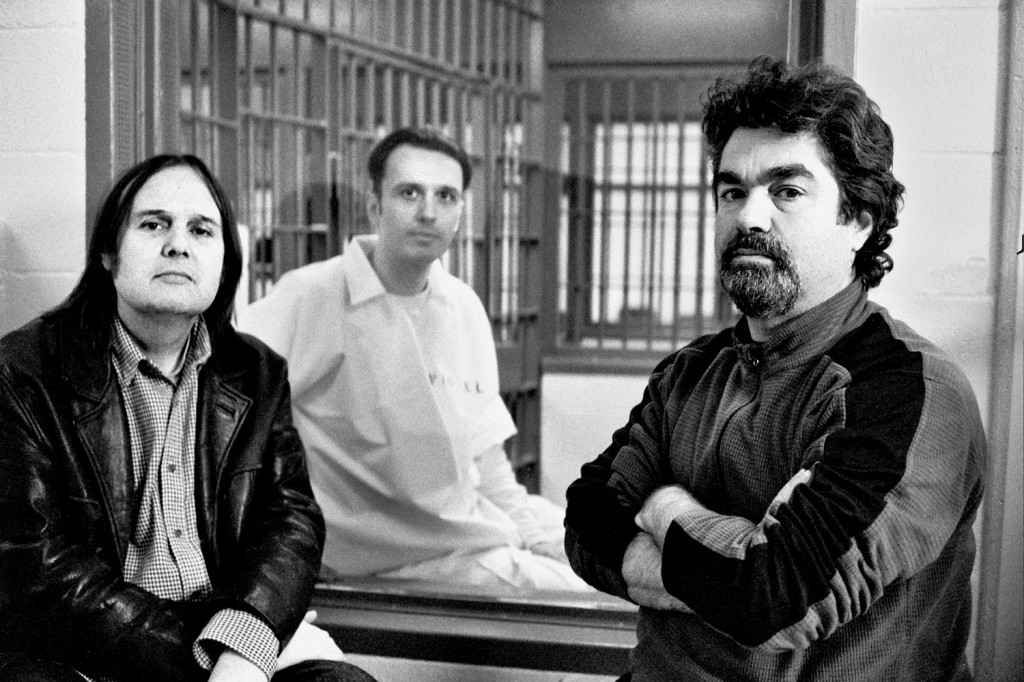

18 years after traveling to Arkansas to make a documentary about the gruesome murders of three young boys by alleged Satan-worshiping teenagers, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky bring their crusading story of the West Memphis Three to a miraculous conclusion with Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory.

On Aug. 19, 2011, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley Jr. entered an Arkansas courtroom for the final time. This was the last place these men, known better as the West Memphis Three, thought they’d be on this summer day — Baldwin and Misskelley were currently serving life sentences and Echols was on death row. But 18 years and 78 days after being sentenced for murdering three 8-year-old boys in West Memphis, Ark., there was finally a glimmer of hope that the state would recognize that these now mid-30-year-old men were not the killers and let them go free. For that to happen, though, the West Memphis Three would have to say they were guilty.

Filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, who had been chronicling the case most of those nearly two decades, took the news with both elation and panic. They were in the midst of locking their latest documentary on the case, Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory, and shipping it off to the Toronto International Film Festival when they flew down to document this latest event. What they found was Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley agreeing to give what’s known as an Alford plea — a guilty plea that nonetheless asserts innocence. Though the filmmakers couldn’t get the new ending in their Toronto cut, it was added for the film’s New York Film Festival screening, where Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley were on-hand; an unlikely finale to what’s probably the end of Berlinger and Sinofsky’s following of the West Memphis Three.

In Paradise Lost 3 the directors use never-before-seen footage from the last two films to show how this miscarriage of justice has continued to affect the lives of not only Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley, but their parents and the parents of the victims. We are also given a glance at some of the new evidence that would have been presented by the defense at a scheduled evidentiary hearing had the option of an Alford plea not surfaced. One of the major findings: the supposed knife wounds on the victims were in fact animal predations.

For Berlinger and Sinofsky Paradise Lost has been a labor of love. The films put them on the map as perennial doc-makers, but the trilogy has also been a grueling process, part filmmaking and part activism. Now as the filmmakers likely put down their cameras, the West Memphis Three story goes on. An adaptation of the book on the men, Devil’s Knot, which has been in the works for years (at one time Berlinger and Sinofsky were involved), was put on the fast track after the men were freed and will be directed by Atom Egoyan. And, puzzlingly, there’s another documentary, West of Memphis. Directed by Amy Berg (Deliver Us From Evil) and produced by Peter Jackson, who’s been a major financial backer of the West Memphis Three defense since seeing Paradise Lost in 2005, the film will premiere at this year’s Sundance Film Festival (Damien Echols and his wife Lorri Davis are also producers on the film). However, many in the doc community are not welcoming it with open arms and believe Berg and Jackson are cutting in on what the Paradise Lost films have built. The tension between the projects became public when The New York Times ran a story before it was announced that West of Memphis was selected to Sundance’s Premieres section, revealing that the film made an exclusivity deal with numerous subjects from the Paradise Lost films, blocking Berlinger and Sinofsky from talking to the subjects for Paradise Lost 3 and forcing them to make similar deals with some of their subjects. (Ironically, Berlinger’s latest film, Under African Skies, which recounts Paul Simon’s historic Graceland album, is playing in the same section at Sundance as West of Memphis.)

Regardless what comes down the pike, Berlinger and Sinofsky will be forever linked to the West Memphis Three. Their documentaries are a testament to what nonfiction filmmaking can accomplish when put in the right hands. As Echols says in Paradise Lost 3, “I really do believe these people would have gotten away with murdering me if it was not for what you guys did.”

Here we discuss with Berlinger and Sinofsky how Paradise Lost 3 culminates 18 years of history-making work, the emotions each have dealt with while making the films and their thoughts on the filmmakers who have become inspired to take the story on.

Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory airs on HBO in January.

Last time we had you in the magazine was for Metallica: Some Kind of Monster and you referenced a “loss of innocence” in regards to making the Paradise Lost films. Is it even possible to conjure a memory from the last 18 years that doesn’t associate with the making of one of these films?

Joe Berlinger: I remember like it was yesterday, cutting the film in 1994, back in the day when you could have a year-and-a-half to cut a film. [Laughs] I had a 6-month-old infant at home, and there was a particular week of editing when we were going through all of the crime scene and autopsy footage and photographs and really trying to decide how much should we put in. I had a new house and a baby, Bruce and I had a new company, so everything was new. I just remember coming into my daughter’s nursery, picking her up and cradling her, and I was brought to tears. I felt like in this experience there were no winners — what had happened to those children was so gruesome, and the fact that the wrong people were blamed for it was haunting us. I think about that moment a lot. It’s a searing memory that really marked me.

Bruce Sinofsky: I have five kids, and I’d say they were very much on my mind when we first did the films. When I see things that my children go through, I think about those [murdered] 8-year-olds. I just don’t think about Damien, Jason and Jessie rotting in jail, I think about teaching my kids how to drive. I think that was something that was robbed of Todd and Mark and Terry of their kids: a mother getting her son ready for his first big date, preparing for applications for college. And obviously I thought long and hard about what Damien, Jason and Jessie were doing in jail, and I was concerned about Damien being put to death. It was always in the recesses of my mind, what these guys were going through. It’s a weird thing, making films about people’s lives at their most difficult. I felt guilty, even going back to Brother’s Keeper, that we made a film about a guy who was accused of his brother’s murder and we’re making a living off of it. It made our careers. If that hadn’t happened then the Paradise Lost films wouldn’t have happened. So there’s the thought that you’re making a living off of other people’s troubles that bothers me a little bit. The fact that the films were successful, that they motivated people to get involved in the case, has always been a happy thing for me, but I have to say, making a living off of the worst days of people’s lives is a little troubling.

Berlinger: Revisiting the same film over and over again is not that exciting creatively. The first film was purely a storytelling experience. It was purely for the cinema. No advocacy. We were here to do a nonfiction feature film about bad guys. By the time we were done it was something completely different. The second and third films were born purely out of a desire to help, and that’s a different mindset. Purely out of advocacy. What I’m proud about the third film is that I think it’s a very nice blending of both really strong storytelling and the advocacy is there.

Sinofsky: The reality is, we figured we’d be telling this story until Damien was put to death, God forbid, or they were released. So we didn’t know if this film would officially be the last one, but we hoped. The way we like to make films is obviously to follow the story. We didn’t think it was going to take 18 years to tell the story, but we were prepared to be there at the end. I think there were times when we were doing the third film where nothing was really going on. So there were moments when we thought, jeez, should we be doing this film or not? But obviously we’re very glad that we did, and it was an amazing ending.

You’ve been working on part three since 2004. Were you shooting constantly?

Berlinger: We were greenlit in 2004, and the case was going glacially slow. Six, eight, nine months would go by, but we would do nothing because there was nothing going on. We made the decision that we couldn’t just rush the film out. Paradise Lost 2 was greenlit in 1998 and it came out in 2000 because we just felt we had to get another film out. For 3, we thought the film should come out when it could really make a difference. For years we didn’t know how to end it or how to structure it, and then the Arkansas Supreme Court granted the evidentiary hearing, the first positive step in their case in 18 years. When we knew there was an evidentiary hearing, that’s when we rushed to finish. The film came out in Toronto with the promise of the evidentiary hearing, and we had an original airdate on HBO in November. We wanted to shine a light and remind people. The advocacy of part three isn’t how we structured it in the story, as in part two, but when we were originally going to air it. In fact, we were going to give the world a preview of what was going to be discussed. The alleged jury misconduct, the animal predation instead of the knife wounds, the hairs, all of that was going to be in the hearing.

What were the challenges of crafting a story for a part three, where you want to appeal to both the loyal followers of the story as well as newcomers who aren’t steeped in the history?

Sinofsky: Even with the second film, we had to have that beginning where somebody who hadn’t seen the first film would at least understand what was at risk and what was going on. Retreading stuff for the newbie.

Berlinger: It was kind of like the Metallica film. How do you make this both rewarding for the fan but, more importantly, bring in new people who know nothing about Metallica and think they have nothing to learn? That’s the same tension we found in making this film. Part two really depends on seeing part one, and I think that was problematic. What we wanted to do with three is make the film a really rewarding and engaging experience for people who know every facet of this case but also make it a completely self-sufficient viewing experience for those who have no knowledge or very causal knowledge of the story. The key to the narrative structure was two-fold. The first two movies were five-and-a-half hours of screen time, so how do you condense that and tell all the new stuff? And does that turn off the fans? We made a pledge that the vast majority of archival footage is footage we’ve never shown before. We combed the footage, and we were horrified that some of our 16mm negatives were damaged, or we didn’t have access to some. Then we realized — and it became a metaphor about the role of media — we could just transfer [the workprints] to video. That’s why you see all those green scratches in the film. That’s the actual 16mm work print from the first movie. And there’s a certain quality to that. By transferring positive workprint shot on 16mm back in ’93, it just automatically says, “this is the old footage.” So for people who don’t know the story, I think we did a really nice job of condensing those elements, [explaining how] these guys were convicted and unmasking why this was problematic. Even if you know the story, you’re still getting something out of this that you haven’t seen before.

The second major part of the narrative structure, and no one really comments on it, is the unfolding news reports over the years. You see the very same journalists growing up with the story and going from pro “devil-worshiping theory” to recognizing something is wrong here and being very supportive. One of the key reasons why pressure started building in Arkansas and that the authorities started paying attention in recent years was because the press started becoming neutral or pro Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley. So the most interesting aspect of Paradise Lost 3 is the use of media to tell the story because its role changed the nature of the information.

Joe, you mentioned earlier that making these films aren’t exciting creatively, but that it was important to make them to advance the cause. Did you feel at all that you had to pass up on opportunities to make other films because you had to continue telling this story?

BERLINGER: Yes, and no. I mean, we’ve done Some Kind of Monster, Iconoclasts, I’ve done Crude and I have a movie on Paul Simon going to Sundance. There are boatloads of commercials. It’s not like making these films stopped me from making other things, but with each [Paradise Lost] film there is a greater and greater set of handcuffs as to what the story is and how to tell the story. The flipside to that is what a unique opportunity to revisit your own work over a significant period of time and figure out how to tell the story for a third time with new information. But I feel emotionally handcuffed because I really want to move on from the story as a human being. My daughter, who was born when we made the first one, is going to college in the fall. It’s time to move on.

Bruce, there is such distrust in today’s justice system and in government, what can be taken away and learned from the three Paradise Lost films to better it?

Sinofsky: It took 18 years to get to the point where they got the attorney general’s office to, in their own way, admit that there was something wrong with what had happened. I think we can’t believe everything we hear. The media, the local media, the bully pulpit of religion in the Arkansas area — they had people on Sundays saying these guys were guilty. If you’re hearing that from someone you respect, it’s going to be very, very hard to be a member of a jury [and not be] predisposed that these guys are guilty. You have to be patient.

Now that Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley are free, is your storytelling of these men over?

Berlinger: When people ask, “Is there going to be a Paradise Lost 4?” we are really resistant to the idea. On so many levels, it just feels like the end of an era. I took Jason to Amsterdam for IDFA, and it was his first time out of the United States. I took him to a concert Sting did at the Beacon, and Lady Gaga and will.i.am performed. It hit me that this guy was in the slammer six weeks ago and now he’s in New York City at his first rock-and-roll experience. The filmmaker instinct is, “Man, I should be filming this stuff,” but Bruce and I feel we’ve had a very unique opportunity to tell a very important story, we stuck with it and now that they’re out, it would feel exploitative to film them outside of prison. It would be one way of making Paradise Lost 4, but it would feel like reality TV. The other type of movie for a Paradise Lost 4 is if we could definitively prove who the killer was.

Sinofsky: As a storyteller, I would love to see these guys in five years and see where their new journey has taken them. I think that would be fascinating. But there comes a time when you have to put the cameras down and let people live their lives. They’re not just there for me and Joe to tell their story. They have a right to privacy. I think the last 18 years were taken away from them, and in a small way, when you put a camera on somebody and are asking them questions, you’re taking away a little bit more of their life. I’m not sure I would want to do that.

Has the Paradise Lost mystique gotten so big that it would be too hard to turn away if you were offered a fourth film?

Berlinger: We can easily step away. The machine has gotten so big. There are other people planting flags and want to tell the story. There’s another book, Peter Jackson’s documentary is coming out, Atom Egoyan’s movie. We and HBO pledged to ourselves that we would continue to shine a light on this case until the West Memphis Three got out of prison, and that’s what has happened.

Sinofsky: For us, it seems like the end of an era and it’s great that this thing can go on just fine without us. But just because we aren’t making films about it doesn’t mean that on a personal level we won’t do everything within our power to continue to fight for exoneration. Hopefully, all of the positive attention that our third film has been getting will help in the effort to get these guys fully exonerated.

The New York Times reported some friction between you and West of Memphis, the new documentary by Peter Jackson and Amy Berg. How did you feel about that film?

Berlinger: We were thrilled that Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh became so inspired to get involved in this case after seeing our Paradise Lost films in 2005. Once they started making their own documentary, we did find it frustrating that we were prevented from filming certain characters who we introduced them to through our films and whom we had been covering for almost two decades. But, at the end of the day, it has all worked out just fine. It was a tremendous personal experience to share Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory with film festival audiences this fall on the heels of the West Memphis Three’s release from prison. Having all three guys attend the New York Film Festival — their first time together since leaving prison — was especially memorable. We are also really excited about our HBO broadcast when all three films will be shown simultaneously on the network thanks to Sheila Nevin’s amazing support. So it’s been a great ride. Peter Jackson has obviously made a huge contribution, so if he thinks that making his own film is the best route for him and the case, we support his decision and hope that West of Memphis will help further the cause of fully exonerating the West Memphis Three.

Sinofsky: Hey, the bottom line is they helped in the investigation and they want these three guys to be free. To me anything that gets them exonerated or leads to further investigations is great. For our first film, we were there every day of both trials and we got to know everyone in town very well. There was a huge trust factor and the access we got in the court room and the judge and the attorney’s, you can’t get that now. Our intensive investigation of this case while it was unfolding laid the ground work for everyone else. But I wish Peter and Amy success, as it can only draw more attention to this gross miscarriage of justice.

The Times also indicated that you had to pay some of your subjects, was that because the West of Memphis project was doing the same thing?

Berlinger: We paid honorariums to two people in Paradise Lost 3, which we disclose in the film. One payment was in response to Amy Berg’s film paying certain subjects for exclusive rights and contractually blocking them from participating in any other documentary, including ours. The second person was paid due to the history of payments connected to the first Paradise Lost film. Basically, in 1993 we had embedded ourselves in the community for almost eight months before the first trial started, filming six families who were dealing with an unimaginable tragedy, some of whom lived below the poverty line. About three months into filming, long after we had established access, we saw that some of these families couldn’t afford basic necessities, and yet we were coming down spending lots of money. We just felt bad that some of these people were having trouble making ends meet, so we gave each of the six families a one time honorarium as a basic humanitarian gesture. We did not want to choose sides, so we gave the three families of the victims and the three families of the accused the same amount. Unfortunately that created an expectation of compensation with one of our subjects that continued into the second and third films. Then, between Paradise Lost 2 and 3, a feature film that eventually became the Atom Egoyan project began to buy life rights from a number of people involved in the case. And finally Amy Berg began to pay some of her subjects, all of which has raised people’s expectations about being compensated. Obviously, the issue of paying subjects is a murky question that documentary makers need to think deeply about. I am not sure I would do it again on the first film if I could go back in time. But on the other hand, when we first blew into town in 1993 with a film crew, spending $300 per eleven minutes of footage that you are shooting — that was the cost of shooting and processing a single 400 foot roll of 16mm film back then — and staying in hotels and spending — and earning — money about somebody’s tragedy and they can’t buy their groceries, it felt like the right thing to do at the time. The bottom line, though, is that we don’t think it’s affected our journalism — after all, we reported on a miscarriage of justice for 18 years and the subjects of the film are now out of prison.

Damien and his wife are producers on West of Memphis, did you know this while filming part three?

Berlinger: The first time I learned that Damien and his wife were producers on the other film was when Peter Jackson issued a press release announcing the film. You know, we filmed Damien 18 years ago being chained up and carted off to death row for a crime he didn’t commit, so I am a champion of whatever Damien thinks is best for him with regard to re-engaging with the world and with the fight to clear his good name. We wish him nothing but success in the effort to fully exonerate the West Memphis Three.