Back to selection

Back to selection

From Hollywood to nobody

Sometimes people ask me how I went from living in Los Angeles, writing a studio film like 40 Days & 40 Nights, to living in Minneapolis, directing an independent comedy like nobody. It’s a fair question but it seems there’s a subtext here, too. Many people think independent film is a step down from the studio system. And I’m sure it is — for some people.

But let’s go back. 40 Days & 40 Nights is about a guy who gives up sex for lent and then meets the perfect girl. The short version of how it was made goes something like this: we pitched it to every studio in town. After nine “no’s,” the tenth place, the last place, said “yes.” (Note that this is not a storyteller’s embellishment; this is 100% true.) I turned in the first draft a few months later. They liked it and essentially the film was greenlit right then. We were filming 13 months after we sold the pitch. The film was released a year-and-a-half later. Internationally the picture went on to make just under $100 million in theaters. Those aren’t Transformer numbers, but they’re very solid, especially for a comedy that cost less than a fifth of that to make.

At the time I believed the film was made because of the script. However, in retrospect I believe it was made because of a confluence of a 20 completely random stars aligning. This included an influx of money at the studio from a new partnership; their recent films had been hits; young comedies like mine were connecting at the time; a few bankable actors in the age range wanted to play the lead; the executive(s) happened to like (or at least think it was commercial) the concept/script; and that the producer was hungry enough that when he hit road blocks, he found other ways to keep moving forward. I can go on, but hope this is enough to illustrate my point: the film was made because of 20 things that had nothing to do with the script.

I did not know this at the time. How could I? I was twenty-eight. I had been in Hollywood five years. Aside from the handful of people I had met since I got there, I didn’t know anyone in the industry. I simply assumed the studio system would always find a way to make something good and commercial. In short, I didn’t know any better.

I spent the next few years entrenched in the system, took writing assignments, spent a year working exclusively with Ridley Scott. The following year Anthony Minghella offered me a script over breakfast. (The studio killed the deal because they didn’t believe in the project). It was fun. I made some money. I learned from people much smarter and more experienced than me. Life was good. There was just one small problem.

None of these scripts were getting made into films.

A couple close calls, but no greenlight. I figured this was because I was writing their ideas instead of mine. I stopped taking assignments, withdrew from the system, and took a year to write what I still believe is the best thing I’ve ever done. The Quiet Type is a story about a small-town mute who falls in love with a New York City chatterbox. This is a romantic comedy wherein the lead character is mute. I wrote it on spec even though at the time I probably could have sold it as a pitch. I did this because I felt like a pitch was mostly about presentation wherein a script is all about substance. The project sold the first hour it was on the market. To this day, even people who don’t like me begrudgingly respect me for that unproduced script and nothing else.

A couple close calls, but no greenlight. I figured this was because I was writing their ideas instead of mine. I stopped taking assignments, withdrew from the system, and took a year to write what I still believe is the best thing I’ve ever done. The Quiet Type is a story about a small-town mute who falls in love with a New York City chatterbox. This is a romantic comedy wherein the lead character is mute. I wrote it on spec even though at the time I probably could have sold it as a pitch. I did this because I felt like a pitch was mostly about presentation wherein a script is all about substance. The project sold the first hour it was on the market. To this day, even people who don’t like me begrudgingly respect me for that unproduced script and nothing else.

I spent a year writing it. I spent another year rewriting it, addressing the notes of my studio executive. We made it better. Two years into it we were finally ready to go to actors. Now, four years later, they were finally going to make my second picture.

And then it happened.

My studio executive took a job across town. My script was assigned to someone else. I sometimes imagine this guy familiarizing himself with the new slate of projects. Having just finished the something about reptiles on a commercial flight, he picks up my script. After five pages he thinks, What the hell? The protagonist doesn’t talk? He flips through to page 30, 50, 70, 100. He’s looking for one thing — the lead character’s name in the middle of the page followed by some dialogue, any dialogue, maybe just one word. But he doesn’t find it because it’s not there. He wonders to himself? Are you kidding me? What the hell am I supposed to do with this?

It’s not his fault. This stuff is completely subjective. What you like is what you like. I liked it; he didn’t. But that’s the whole problem. It’s no one’s fault.

Some version of this sad story has happened to thousands of screenwriters before me and I’m sure hundreds since. But that’s when it hit me — I wasn’t writing movies; I was writing screenplays.

While that’s a perfectly fine way to make a living and support a family, it’s kind of a silly thing to dedicate your life to. I got into this business to make people laugh, feel, and think. When I say “people” I’m not talking about a couple of movie executives, agents, and producers, you know, the ten people who read scripts. I’m talking about real people. Regular people. Actual people. You know… people.

I had to at least try to get back to making movies.

It was now 2007. Six years without a film and the horizon was looking bleaker everyday. Hollywood was changing. Studios now had to answer to parent companies. Development money shrunk. Slates of films being produced were slashed in half or, in some cases, by two-thirds. And those films, the vast majority emphasized marketing potential over material. In other words, most weren’t even trying to be good films; they simply wanted to be commercial. On a personal level, this meant the films the studios were making were no longer films I wanted to see. This blew my mind because I never thought of myself as an art house guy. I love John Hughes, John Landis, and Blake Edwards. It’s not that I grew up with these guys. I want to be these guys. I want to affect audiences the same way they affect me. But if the studio system suddenly didn’t have a seat for them at the table, was there really a place left for me?

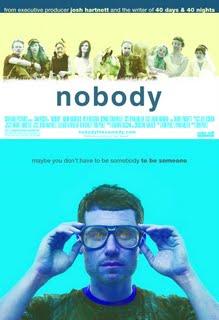

Meanwhile, in 2003 I had co-written this script called nobody with Ryan Miller, lead singer of the band Guster. It’s a comedy about an artist looking for inspiration. It was intentionally smaller in concept, scope, and ambition, conceived and executed for a first time director — me. I feel like a lot of first timers fail because they try to bite off too much their first time out of the gates. I wanted keep the world relatively contained and give myself a shot of actually pulling this off.

Early on a few name actors were interested, but not anyone I loved. Of course signing up the flavor of the week was tempting, (hey, instant financing!) but I made a promise to myself that I would keep to the end: try to make a picture I would want to see.

I also figured finding a leading man was a little like finding a house. You know it when you see it. Four short years later I found my house doing a one-man show in New York City. I went back three times that week and, after convincing this unknown named Sam Rosen I was not a stalker, got him to read the script and accept the lead role.

Problem is, Hollywood not only didn’t want to finance a small picture with this guy, they didn’t even want to meet him. Thus, I went looking for independent financing. The script was set in Minneapolis. Coincidentally, Sam Rosen, the lead, and Josh Hartnett, the executive producer, were also from the Twin Cities. I started pounding the pavement there. I flew back and forth from Los Angeles to Minneapolis every other month, meeting with people, hat in hand. They were interested but after a few close calls I saw what was holding them back. A little part of them was afraid I was going to take their money and move to a tropical island. If I could convince these potential investors that I was trustworthy, that my only plans with their money was to make this movie, that I was one of them, then I felt they would jump in.

In the fall of 2007 I threw everything I owned in storage and moved to Minneapolis. We were fully financed within six months. Roughly ninety percent of that money is private equity from the twin cities.

We completed principal photography in July, 2008. We are just now gearing up for a world premiere here in Minneapolis and, hopefully, at the very least, a local theatrical run. Truth is we haven’t had much luck with festivals. At first this was hard to swallow and even comprehend until I showed it to a group of my filmmaker friends, people with a ton of festival experience and success, and they all said more or less the same thing: You made a film for high school and college kids which is not the demographic the festivals want.

We completed principal photography in July, 2008. We are just now gearing up for a world premiere here in Minneapolis and, hopefully, at the very least, a local theatrical run. Truth is we haven’t had much luck with festivals. At first this was hard to swallow and even comprehend until I showed it to a group of my filmmaker friends, people with a ton of festival experience and success, and they all said more or less the same thing: You made a film for high school and college kids which is not the demographic the festivals want.

In other words, this isn’t art; it’s entertainment. Thing is — that’s exactly what we set out to do. Is it perfect, a classic, the best picture ever made? No, no, and yes. Okay. Maybe I overstate that last part because I’m all too aware of its shortcomings. A few mistakes are a function of time and budget, but the vast majority are one-hundred percent my fault. Some jokes don’t land. The camera isn’t always in the right place. And in one particularly painful moment, the staging is reminiscent of elementary school theater. I can go on but won’t because I choose to take solace in that old saying about how no one starts directing their third picture.

Plus, there are a lot of things that actually work in here: there are a bunch of great laughs; the relationships elicit real emotion; and one or two moments might actually be great. Oh, and my leading man kills it. But most importantly to me, for this film’s demographic (ages 14-22), this is a journey that adds up emotionally to much more than the sum of its parts.

I made a film that I want to see.

In the end, I feel the exact same way about this film as I did about 40 Days & 40 Nights. I’m incredibly proud of this thing. Truly. But if this is the last film I ever make I will have fallen short.

There’s still so much more to do.

nobody will have its world premiere October 1, 2009 at Minneapolis’s State Theater, with tickets available through Ticketmaster, and will open October 2 at Minneapolis’s Kerasotes Block E. For more info on these and other upcoming screenings, visit the nobody website.

(Photos: top, Perez with actress Helena Mattsson; middle, poster; below, Perez on the set.)