Back to selection

Back to selection

The Blue Velvet Project

Blue Velvet, 47 seconds at a time by Nicholas Rombes

The Blue Velvet Project, #137

Second #6439, 107:19

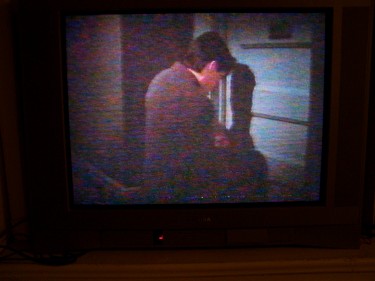

Jeffrey is about to enter Dorothy’s apartment where he’ll find a hellish scene of Frank’s human butchery. The frame captures his vulnerability, his exposed back to the implied danger of the frame’s open space. The red light at the end of the hall, the sharp-edged shadow across the far door, the tar-pit black hallway floor, and the faint ringing noise on the soundtrack, like something deeply broken in the building itself, all conspire to create a feeling that verges on existential terror. In the pan and scan 1987 VHS version (the photo below is of the film on my television) the image is cropped to delete the red light, which might be a more significant object in the frame than Jeffrey, an object that suggests the final terror about to unfold.

And yet despite its apparent limitations, there’s an aura of fascination surrounding the analogue image. Part of it stems from nostalgia and a desire for the warmer, grungier image and its aura of authenticity (perhaps because these images somehow correlate to the way we visualize our memories) in our era of HD clarity. Analogue (in image, in sound) asserts a human presence in the face of smooth, invisible digital data, a sort of human signature: the signature of imperfection. In his essay “The Grain of the Voice,” Roland Barthes wrote that “the ‘grain’ is the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs.” In HD, the grain of the image all but disappears. As we enter into the era of 48 frames per second, image imperfection will either disappear or be redefined in ways that we don’t yet understand.

“When the world, or reality, finds its artificial equivalent in the virtual, it becomes useless,” Jean Baudrillard wrote in Impossible Exchange:

When everything can be encoded digitally, language becomes a useless functions. . . . When artificial memories reign supreme, our organic memories become superfluous (they are, in fact, gradually disappearing). When everything takes place between the interactive terminals on the communication screen, the Other had become a useless function.

Baudrillard was not a reactionary, lamenting the loss of our embodied selves, but rather a chronicler of a moment in time. And although his argument may seem remote from the Blue Velvet frames in question here, we see in these frames not just evidence of image display advancements, but more poignantly evidence of our current ideological imperative; the drive to perfection, for instance, that gives rise to the assessment industry that shapes educational policy. In this environment, it makes sense that cinematic spectacle today has everything to do with the hyper-realistic impulse of our images, to get them closer to the so-called real, to make them more perfect, until there are no gaps left between lived, organic experience and represented experience.

Which is to say: the Jeffrey from the 1987 VHS frame and the Jeffrey from the 2002 DVD frame are from two radically different versions of Blue Velvet, both artifacts of an ideological moment.

Over the period of one full year — three days per week — The Blue Velvet Project will seize a frame every 47 seconds of David Lynch’s classic to explore. These posts will run until second 7,200 in August 2012. For a complete archive of the project, click here. And here is the introduction to the project.