Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions with Searching For Sugar Man Director Malik Bendjelloul

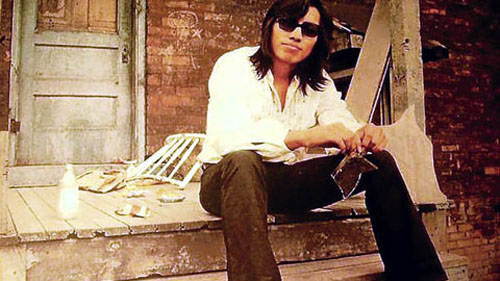

When Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul first came across the story of ’70s singer/songwriter/cult-hero Rodriguez, it must have seemed too good to be true, especially for a music-focused documentarian. Sixto Rodriguez, the Detroit-based troubadour who blended street-savvy folk, rock, and socially conscious soul on two under-the-radar early-‘70s albums, was completely unknown in America (and almost everywhere else) for decades. But in a twist worthy of an O. Henry story, Rodriguez (who has always worked solely under his surname), somehow ended up an iconic figure in South Africa, where his reputation assumed Bob Dylan-esque dimensions. The catch: most South Africans have long assumed he was dead, a rumored onstage suicide. And until recent years, Rodriguez remained unaware of – and uncompensated for – his popularity there, supporting himself and his children for years as a manual laborer in Detroit.

Bendjelloul — whose previous credits include a number of music documentaries for Swedish TV, but who had never directed a feature film before – wasn’t the first to unravel the Rodriguez mystery. But with Searching For Sugar Man (the film’s title comes from one of Rodriguez’s signature songs), he’s helping to bring the Rodriguez legend to the world at large. The singer, now 70, already emerged from the shadows to play for hordes of ravenous South African fans, as well as making himself available for a drama-drenched “big reveal” after the film’s Sundance screening. And after Searching For Sugar Man’s July 27 New York/L.A. opening, (not to mention the release of the soundtrack album drawing tracks from both of Rordriguez’s records) this stranger-than-fiction true-life tale will make the mysterious balladeer a hero to a whole new audience.

Filmmaker: How did you first encounter the Rodriguez phenomenon?

Bendjelloul: I found the story in ’06. I was working for Swedish TV, and then I quit my job and went traveling for six months in Africa and South America, literally looking for stories – I went with a camera, scouting for good stories. I found a few good ones, I thought, but when I came to Cape Town, I met [record store owner] Stephen “Sugar” Segerman, and he told me this story about Rodriguez, and I was like, “Wow, this is the best story I’ve ever heard. I’m in love with this story.” I thought it was like a fairytale, almost, like Cinderella or something. It was a true story, but it had the qualities of a really good fiction story. I thought this could be a feature-length movie. I started in ’08, and then I worked for four years straight to make that happen. I would never have started if I knew that it takes so much time. I had been thinking maybe one year maximum, and then it took me four years. The main problem was financing: I was 75 percent finished after six months, and then the last three years was basically working on the last 25 percent.

Filmmaker: Why do you think Rodriguez’s records became so popular in South Africa?

Bendjelloul: That’s hard to say. The way I figure, it’s stranger that he didn’t become famous in the rest of the world, or at least in America. I spoke to a friend in South Africa who had seen the film…he said he knew the story because of course he knew Rodriguez. He said that he had a conversation with an American about a year ago, they were talking about something completely different, and he said, “Oh, that would be like imagining the ’70s without the Stones, The Beatles, and Rodriguez,” and the American said, “What did you just say? Who is that guy?” But that was who he [Rodriguez] was in South Africa; he was up there with the big ones. More or less, it’s about the songs, but he became this important figure. He sang this song called “[This Is Not a Song It’s an Outburst or] The Establishment Blues,” and in that song, he sings, “The system’s gonna fall soon to an angry young tune.” And those words weren’t heard in South Africa [on the radio], they were censored, but still he was heard. What happened was that the first white South African resisters against Apartheid came from a few rock bands, and they say Rodriguez was their biggest inspiration. You could justifiably say that Rodriguez was a part of what happened in the country; he had a pretty important role to play.

Filmmaker: What kind of emotional impact do you want the film to have?

Bendelloul: I hope it’s gonna be an emotional ride. It’s really a “poor guy wins” kind of story. A lot of great artists get their recognition after they’re dead, but Rodriguez has something very few people have — I mean, he was dead, and then he came back from the dead. From the celebrity perspective it was like learning that Elvis is alive. And of course that is a very emotional experience. I hope you can get some kind of hope that your life is never over, you never know what can happen in the future. He thought his career was over, and it wasn’t. He didn’t do music — he went on with his life. He didn’t even wait; he didn’t expect anything to happen. And then it [success] comes in the latter act of his life. He was 58 when he learned about the South Africans – he wasn’t old, but he had had a long life without any success.

Filmmaker: What kind of challenges did the production pose for you as your first feature film?

Bendjelloul: There were a lot of them. I was very hard to get funding. Because I didn’t get funding, to just do something [rather than] to wait forever, I thought to do stuff on my own. I started to do animations that I needed money to get professional people to do; I couldn’t get any money, so I did the animations myself. I did the soundtrack myself, on Logic Express, $150 music software for an iMac. I did the editing myself. This is not supposed to be the “real” film, because the real film, there would be professionals coming in and helping me. And then it just continued like that without getting any money, and in the end the film was sent to Sundance, and it was accepted in that state that only contained what I thought were sketches. And then the film was finished. It was only when we learned that it was the opening night film at Sundance that we kind of accepted it: we would not have time to bring in professionals to do the finishing, the final version. Art is never finished — it’s only abandoned, as they say. I’m happy with what happened with the film, I really am. It couldn’t have been much better. I had no expectations, to be honest. I was very surprised that I did an entrance to Sundance. Everything is kind of a bonus, so right now there are a lot of bonuses.

Filmmaker: What was it like bringing Rodriguez out to meet the audience after the Sundance screening?

Bendjelloul: It was wonderful. It is a film about recognition, and it feels like everything that happens with the film, and everyone that makes it happen — like you for example, right now — is part of the story. You are right now forming the next chapter in his life, because it is about this, it is about someone who never got any recognition in his life, and wanted it, I guess. Someone that did something great and didn’t get any reward, and it seems like everything that happens is like another movie…it’s like the next chapter every day. David Letterman’s gonna bring him on his show on August 14, and this is a guy who never played to more than 300 people in America, and wanted to play to more people. It is something quite beautiful that happened.

It was really my dream that this would happen. And if it could only happen once, that he came out after the film and met the audience, I thought it could be really powerful: people meeting the guy they thought was dead 40 minutes earlier. And it really was. And now it’s happened many times, that Rodriguez comes after the film to many festivals. It’s always the same thing – it becomes completely crazy. People are screaming and crying; he always gets a huge standing ovation. People are so much in awe, with love and respect for him. He has experienced similar stuff in South Africa, where he had thousands of people almost fainting because they’re overwhelmed to see him. But there have been a few screenings where people have really gone crazy. I think it is kind of a surreal experience [for him]. It’s hard for me as well to take everything in, to be in the moment and enjoy it. You do it, of course, but when it’s over you almost feel like it was a dream or something. It’s a weird explosion of happiness.