Back to selection

Back to selection

The Blue Velvet Project

Blue Velvet, 47 seconds at a time by Nicholas Rombes

The Blue Velvet Project, #151

Second #7097, 118:17

(Note: the final post in the project goes up Friday.)

A confession, of a different sort, about how a movie saved a young man. Can a scene from a movie detour your life, turn you in a new direction? I think it can, in the same way that a book read and just the right age can, or a band can by the sheer force of its ideas turned sonic. (One of the self-imposed rules for this project was to avoid the personal, the anecdotal, but figuring this is the second-to-last post . . .)

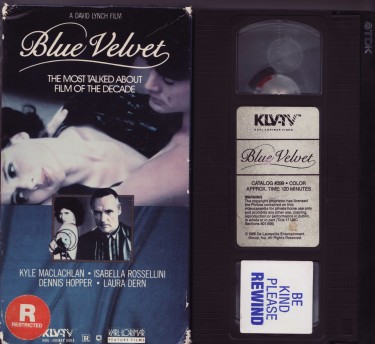

Blue Velvet was recommended to a creative non-fiction class I was in during college by a professor who, in retrospect, I’d say was in the midst of something like a nervous breakdown. (A week before the incident below he had hurled a baseball at what he thought was an open classroom window to illustrate a point about the importance of taking risks in writing. I suspect he knew the window was closed.) This was in 1987, and Blue Velvet had just been released on VHS by Karl-Lorimar and was available for rental (I also had to rent the VHS machine) at Real Video in Bowling Green, Ohio.

The semester was winding down, and the professor—in the guise of trying to make a point about the importance of the small moment in writing—began to tell a story that quickly overtook him. I don’t remember how it began, but it ended with him gripping the back of the chair he stood behind, trying to hold it together, working so hard to hold back tears that the room itself became hyper-charged, charged enough that a few of us decided right then to become writers no matter what, as if the professor was transmitting some secret signal instructing us to do just that, and as if the whole semester had tended toward this final performance.

His story involved a broken romance, something that had clearly killed a part of him. The part I remember was the end: he sensed something was wrong between the girl and him, and he drove through the night deep into the country where she lived, on a farm. The house was empty and dark, but there was a light from the barn. He walked through tall, wet grass. He also said something about the cricket noises sounding unreal, as if they weren’t coming from crickets, but something else, something not natural to this world. In the barn there was the girl’s father, shirtless, slaughtering an animal beneath some powerful lights he had rigged up. He held up the animal’s heart to my professor and in that moment he took that act to be symbolic: this is your fucking, bloody heart, ripped out of your chest by my daughter.

That was it. That was the story. But it wasn’t quite the end, because it was then that the professor mentioned Blue Velvet, as if that was the coda to the story. I don’t remember if I had heard of the film before that, but I do remember I rented it that afternoon, and watched it that night, and that in the following weeks the scenes leaked and bled together in my mind. But it was the last scene, as the soundtrack transitions from “Mysteries of Love” to “Blue Velvet” sung by Dorothy herself as she and her son Donny embrace, in slow motion—it was this scene that worked on me like a transfusion, replacing a part of my old self with something new.

Those moments saved me from a vague, spreading darkness that had been collecting in the stray moments of my thoughts. I don’t know if it’s possible—in a sort of Cronenbergian way—for a moment from a film to actually become part of you in a real, visceral, biological sense. Can a few moments of sounds and images and colors become literally sequenced into our DNA, making the leap from art into life? Is it possible to speak of a movie as a biological species, a movie as an organism, a living thing, whose codes aren’t analogue or binary but genetic?

And by its life, a movie that can save you?

Over the period of one full year — three days per week — The Blue Velvet Project will seize a frame every 47 seconds of David Lynch’s classic to explore. These posts will run until second 7,200 in August 2012. For a complete archive of the project, click here. And here is the introduction to the project.