Back to selection

Back to selection

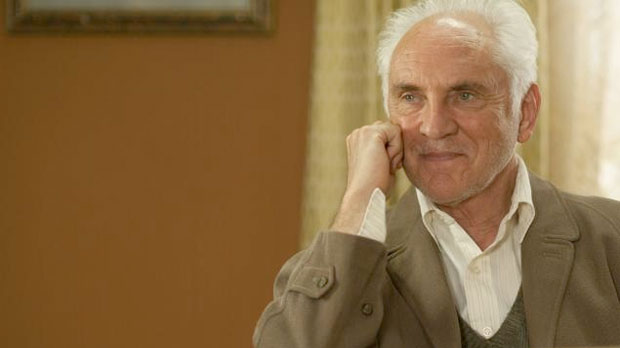

Talking Legends with Terence Stamp

The 2013 edition of the Palm Springs International Film Festival was filled with glitzy events and screenings, including a Talking Pictures sidebar featuring movies followed by conversations with noteworthy actors like Alan Cumming (discussing Any Day Now) and Naomi Watts (for The Impossible). But it was the closing night gala for Paul Andrew Williams’ Unfinished Song, starring Vanessa Redgrave as a cancer-stricken septuagenarian in an old folks choir, that really grabbed my attention. Actually, it wasn’t the film (which I haven’t seen) so much as the possibility of interviewing the actor playing Redgrave’s character’s devoted husband that made me stand up and take notice.

O.K., I’ll be honest, journalistic integrity be damned. I’ve been head over heels for Terence Stamp ever since I first saw Pasolini’s Teorema decades ago. I assumed he’d be magnetic and charismatic (since sexiness never ages), but I wasn’t expecting the pure graciousness and openness that Stamp exuded when I finally got the chance to speak with him over the phone. Whip-smart and quick to laugh, Stamp has worked with a who’s who list of the greatest directors of the past half-century (to be able to say that Buñuel and Visconti were the only two auteurs you didn’t work with is truly saying something). In other words, Stamp is everything one could want in a matinee idol even to this day. Especially today.

Filmmaker: Interestingly, you’ve been on my mind. I was just in New York, and I saw the [Pier Paolo] Pasolini exhibit while I was there.

Stamp: Oh, really?

Filmmaker: Yeah, did you know about it? They’ve got a huge retrospective at MoMA, and they’ve got an exhibit at P.S.1 with Teorema, Salò and Medea. It’s gorgeous.

Stamp: Wow.

Filmmaker: Considering that I just saw the Pasolini, I was hoping maybe you could discuss a little about what it was like to work with him — and also Fellini — in the ‘60s when you were living over in Italy.

Stamp: Right, right. Well, I’ll give you a good idea if I say that when I think about my career — which in truth has been rather long — I think of it as “before and after Fellini.” You know, because he made an incredible — an indelible impression on me as an actor and as a person. And also, when I was there in Rome for the first time, working for the great Federico, he was responsible for introducing me to a new dimension of people, really. Before Fellini, I was very successful but inside I was kind of just an East End spiv. So I was kind of winging it really as an actor, you know?

Filmmaker: But you had already gotten the Academy Award nomination.

Stamp: Yes, I know. [laughs] But that was pure intuition, you know? And, in other words, my life really changed during that time I was working with Fellini in Rome. Also, when I was in Rome on that same trip, he had the wonderful Piero Tosi doing my costumes for Toby Dammit. I mean, not that they were extraordinary, but Tosi was extraordinary. I think he was one of the greatest costumers I ever met. I was walking in Villa Fortino one weekend and I ran into Piero Tosi. And he had with him Silvana Mangano who had been a sort of wet dream for me as a boy. I had seen her in Bitter Rice. And she was rather taken by me, and she was the one who recommended me to Pasolini.

So it was through her that he was interested in me. And curiously, I had virtually nothing to say about Pasolini, really; other than the fact that I didn’t meet him on that trip. But she recommended me to him and he flew to London with Franco Rossellini, who was Roberto Rossellini’s nephew. They stayed in Claridge’s, which I thought was a little ironic considering he was a sort of real left-wing activist.

And he didn’t speak any English; and using Franco as a translator, at the meeting with him, he said to me, “This is a story of a petit bourgeois, Milanese family. There is a father, mother, son, daughter and a maid. A guest arrives. He seduces everybody and leaves. This is your part.” And I thought, “Well, that sounds like me.”

Filmmaker: [laughs]

Stamp: And that was really the only interaction I had with him, because on the movie he didn’t actually communicate with me at all. If he needed to direct me, he would tell Laura Antonelli; and Laura Antonelli would come up to me just before a take and say, “Pier Paolo wants you to get an erection for this scene!” So that was the only kind of direction I got from him. But, what was unusual was that it took me a few days to work out that he was actually filming me when I wasn’t performing. It took me a while to realize that he had a little camera. He held a camera of his own and he was just shooting me, sort of sitting around the set and stuff. And obviously my main memory of the experience was I got to neck Silvana Mangano, you know. [laughs] Which was my main reason to do the movie.

Filmmaker: [laughs] That’s not a bad reason though, you could do worse than that.

Stamp: No, no, no it wasn’t a bad reason at all. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Oh, my gosh, I had no idea. I thought Pasolini spoke a little English. I guess he didn’t speak any at all.

Stamp: No, he didn’t speak any English at all. Certainly, he didn’t speak any English with me. I don’t think he spoke any English at the time. He may have picked up a bit later, but at the time he only ever spoke Italian. And, as I say, he never actually spoke to me at all.

Filmmaker: That is really interesting. It sounds like it makes for a very strange film shoot, if you’re not actually communicating with the director. I guess Fellini spoke a little bit more English, correct?

Stamp: Fellini was like a soulmate to me.

Filmmaker: So, Fellini spoke English with you on the set?

Stamp: Fellini spoke wonderful English. It was kind of love at first sight, really. I mean the fact was, he loved you but the price was that you had to love him. But that wasn’t difficult in my case.

Filmmaker: But you never worked with Rossellini, though. I’m surprised.

Stamp: No, I think that by the time I was there, I don’t think Rossellini was working anymore. I would have liked to have worked with [Luchino] Visconti. I met Visconti and we liked each other, but I don’t think he was working much either.

Filmmaker: That’s really fascinating. I’m so fascinated with the ‘60s, and you were really at the heart of it, when all the great films were coming out. To have that buzz around you at all times.

Stamp: Well, the thing was, you know, if I look back on it, it just seemed I was really blessed. Even more than privileged. Because I was sort of discovered by Peter Ustinov, my first Hollywood movie was with William Wyler; I then worked with Joe Losey and John Schlesinger and it was just kind of a magic time, really. And when I went to Rome, I guess I was the first English actor to kind of play a lead in a Fellini movie. I think; I’m not sure. But that’s what it felt like.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting when you speak about this, because I actually interviewed Malcolm McDowell a few years ago because there was a Lindsay Anderson retrospective in New York as well. And it’s very similar. He felt he was in the right place at the right time, and he got very lucky to get to work with people like Kubrick and Lindsay early on in his career, when he could still be shaped by these legendary directors.

But I’m also kind of wondering, did that make you become spoiled, because you had such great people working with you early on? Or does it drive you to seek out more artistic experiences, or is it still about the money sometimes?

Stamp: Well, in my case, what happened was, you know, to have my first film experience with Ustinov was probably the greatest thing that could’ve happened to a young actor. Because although he wasn’t the greatest director I ever worked with, he was one of the greatest men I ever met. So, consequentially, I was given a life lesson, really. Just by observing him and being with him. He and his wife kind of adopted me, so after the movie I sort of traveled with them.

And at the end of the film, I remember on the last day of the movie, he said to me, “I think we’ve done something really special here. And I think other people will try to cash in on it.” And he said, “I just want to tell you that if you do good things, good things will come to you.” And I think, because it was him, I probably took that a little too much to heart; with the result that I didn’t really work for a year after that. But the truth is, I’ve clung to that. So, there are times where I have to do rubbish. But I only do that when I haven’t got the rent. But, other than that, I just do things I intuitively feel are going to be good for me; and I figure if they’re good for me, they’re good for the movie, as it were.

And then it did seem to me, because in the ‘60s there were only a couple great directors I didn’t work with. I didn’t work with Buñuel. I would love to have worked with Visconti. But, apart from that, I just worked with the best really.

And then I was out of work for almost the whole of the ‘70s. And in answer to your questions, when I got my comeback, I got my second break, and I came back to do the Superman movies, I kind of realized it was almost like I was my own director. I was actually putting into effect what I had learned from all those great men. So, although I did work with wonderful directors obviously, I didn’t have the kind of reliance on them that I had in the ‘60s. I felt confident enough to…I was kind of close enough to myself to just kind of, you know, use my own intuition between “action” and “cut.”

Filmmaker: Well, the student becomes the master once you incorporate all the things you experienced. You’re able to use the lessons without that person being there to direct you.

Stamp: Yeah, but no, no, that happened to me quite naturally. I didn’t really think, “Oh my God, where are these great directors?” Because I had been out of work so long, I really thought as weeks became months, and months became years, by the time we got to ’77 I was really thinking, “Maybe I won’t get recalled. Maybe I should think about living my life without being an actor.” So, when the Superman role came up and when the movie came up with Peter Brook [Meetings with Remarkable Men], I was just so delighted. And it was only afterwards that I thought to myself, “Oh yeah, I can do it on my own now.”

Filmmaker: Did you ever do theater?

Stamp: I did a lot of theater before I got discovered by Ustinov.

Filmmaker: That’s what I thought.

Stamp: Yes, I did years. I did weekly rep, I did two-weekly rep, I did monthly rep; and I did more things in the West End. But basically, once I’d experienced film, I thought, “This is me.”

Filmmaker: You had no desire to go back to theater at all?

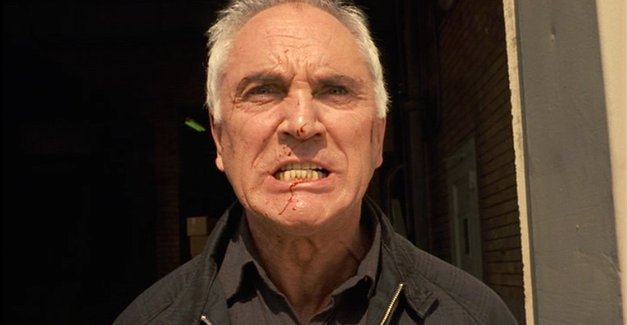

Stamp: I had no desire. Occasionally I did, like I did Dracula in the West End and it was a terrible flop. The critics seemed to want to put a stake through the heart of Terence, you know? [laughs]

Filmmaker: [laughs] Personally, I would love to see you on stage. I think that would be brilliant.

Stamp: Well, the thing is I ended my stage career. After Dracula, I did The Lady From the Sea with Vanessa [Redgrave], which was an Ibsen thing in the Round. And it was a part that had been considered unplayable; the role of the stranger in The Lady from the Sea. And I wanted to work with her. I knew the part was kind of impossible, but I thought of a way I could maybe do it. And I wanted to end my theater career on an up, rather than having been crucified in Dracula. And I managed to pull it off, largely because of her. And also we had maybe the greatest director we had in England, a guy called Michael Elliot, who was unusually sensitive, and miraculously, was open to all of my kind of eccentric ideas.

So, that was the last thing I did. I still do live, but I can’t do it all. I lost the muscle for the night after night procedure. The things I do, I do one-off. Like I narrate symphonies, I do readings and appearances. I have no desire — I can’t really. I don’t think I could do eight shows a week. Even by the time we did The Lady from the Sea, which was a big, big hit I must say, it was becoming a struggle after the first fortnight. I was finding it difficult to reproduce — to have the same spontaneity as I had the opening weeks.

Filmmaker: Yeah, it’s work, the grind day after day.

Stamp: And as the years have passed, for example when I worked with Soderbergh, when I did The Limey, because he was the cameraman as well as the director on that film it was, like, one take, you know? There was only one scene where I had a big speech, and Soderbergh said to me, “Can you bear to do another take? I want to change the camera angles.” [laughs] And he loved me because he was the first-take guy as well.

So, when we did Song for Marion [original title of Unfinished Song], the director [Paul Andrew Williams] — who was a young director, he made one film but it was a kind of a gem; it was a thing called London to Brighton. And that had kind of convinced me that I could trust him as it were. But, in the second week, he was on the set and said rather loudly so the crew could hear, “Wow, you guys—you and Vanessa sort of nail it on the first take.” And I said, “Listen Paul, when you’ve got Vanessa Redgrave and Stamp, you’ve got a hundred years of movie acting.” And everybody laughed. And I looked at Vanessa and said, “Well, actually it’s like a hundred and one, right?” [laughs]

But, it was a fact, you know?

Filmmaker: How long have you known her?

Stamp: I’ve only known her since The Lady from the Sea, which was I guess 1978, let’s say.

Filmmaker: Okay, 30, 35 years, that’s a nice long relationship.

Stamp: Yeah, it is. Though, the truth is, I don’t know her socially. But, the fact is, I’ve worked with her in the theater and I’ve worked with her on film, so that’s the best really.

Filmmaker: Well, that was my thought with Unfinished Song, that she was the draw for doing it. Am I correct in saying that? Was it a project you wanted to work on because she was involved with it?

Stamp: Well, ultimately it was, and I’ll tell you the story. I’ve told the story before, but it might be intriguing to you. In my youth I turned down the great Josh Logan, who wanted me to play King Arthur in Camelot. And he actually begged me. He actually went down on his knees in an Italian restaurant in London; he actually begged me to do it. And I was just frightened, you know? I didn’t believe that I could sing that wonderful score.

I felt like I would probably be re-voiced, and for a young actor that could’ve been the end of my career, really. So I had good reason to be fearful, but the truth is, over the years, it’s the only project I wish I had done. And I often think about it, strangely enough. I think, “What a mark, you know? What a wonderful thing, at age 26, to have played Camelot?”

And then, I had my doubts about doing Unfinished Song, because I realized it was the kind of twin soul relationship in so far as they were never unfaithful — he never loved anybody else, she never loved anybody else. And I think these days, that’s rare that that’s depicted in a working-class milieu. In other words, one thinks of twin soul as Layla and Majnun, or Romeo and Juliet, and I thought the beauty of the screenplay was that they were ordinary. And I can do ordinary, but I don’t do ordinary very well. I thought to myself, “The film is going to be better if they find an actor who can do ordinary very well.”

And then, when I met the director, I kind of liked him. And then suddenly, when he told me, “Oh, Vanessa’s playing your wife,” I thought, “My god, she played Guinevere, the character’s name is Arthur and I get to sing.” So, I realized maybe this is the universe giving me a second try. And that convinced me really. So, I was fearful about playing an old-age pensioner, and of people knowing how old I was in reality; so, I was about to walk through a door that I wouldn’t be able to close. And I still had the problem of the singing. But the fact was that, during those years, I had never stopped studying my voice.

Olivier had said to me, when I met Olivier in my early years, he said to me, [impersonating] “You must always keep studying your voice, young Terence, because as your looks fail, your voice will be empowered.” So I’d never stopped studying. So, though I hadn’t sung publicly, I was much more confident than I had been when I was turning down Camelot.

Filmmaker: Wow, that’s beautiful. That’s a really beautiful story to close with.

Stamp: Oh, thank you.