Back to selection

Back to selection

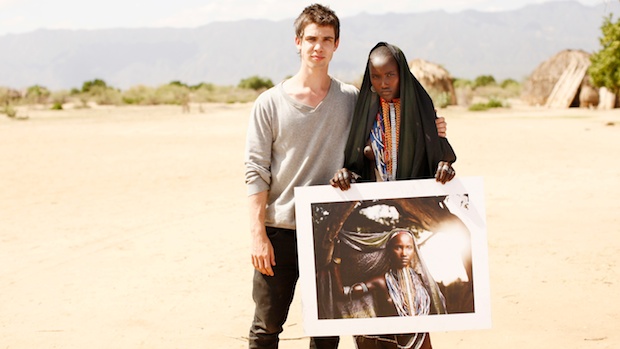

Seven Questions for People of the Delta Director Joey L.

Is it possible to produce a cinematic narrative based on the collective wisdom of a tribe with no real actors? Can a film be made where true stories are brought to life by the people who have actually lived them? Joey L. not only believes it is possible, he has every intention of making it happen.

By the age of 18, he was commissioned to photograph the movie poster for Twilight. Currently his work, on National Geographic’s Killing Lincoln promos, can be seen on billboards from Times Square to Sunset Boulevard. So how does someone who makes a living routinely photographing the likes of Robert DeNiro, Jennifer Lawrence, and Jessica Chastain find himself in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, a remote, inhospitable region so far off the grid that not only is there no electricity and no cell phone service, there is no written language? How did he go from a loft in Brooklyn, NY to sleeping on a makeshift bed of clay and wood for over a month? More importantly, why?

I decided to sit down with Joey L., photographer, director and published author, to find out exactly that.

Filmmaker: What is the genesis of People of The Delta?

Joey L.: I’ve been traveling to Ethiopia’s Omo Valley for over four years now. What started as a slight fascination with the ethnic diversity of the tribes living in area\ has now turned into numerous personal photography trips and adventures. In effect, the people who inhabit the region have opened up to me and feel more comfortable sharing their unique way of interpreting the world.

Up until this point all of my trips have been mainly for still photography. However, now that I have a better understanding of the area, I feel like there’s so much more potential to share stories with a film project like People of the Delta. But it’s not just all about me. Aside from my local team of translators and guides, I have a great team of talented people lending their expertise from the filmmaking community, such as cinematographer Sean Stiegemeier, RC-Helicopter pioneers Snaproll Media and producer Susie Hayasaka.

Filmmaker: Why is it important for this film to be made?

L.: We find ourselves in a critical moment in time to make this film happen. Many of the tribe’s traditions are endangered. Even over the last four years I have seen tremendous changes with my own eyes. Having said that, I don’t want people to think I believe these tribes live a sort of unchanged “noble savage” way of life — all cultures on Earth have always been in a state of transition, including these tribes. However, when we lose a language or way of life, we lose a unique identity shaped over time that will never be repeated on Earth again.

There are some tribes in the Omo Valley that have languages that only a few thousand remaining people speak and traditions that are unique to their ethnic group only. We hear a lot about endangered animals and ecosystems, but we seldom hear about endangered cultures.

Filmmaker: This is not a documentary. This is a cinematic narrative based on stories from the tribe. A very unique approach. Can you elaborate?

L.: The tribes are going to play themselves! This is not a film that I’m going to create on a Hollywood set with actors. These are the real people collaborating in the writing process, as well as the production itself to create the most intimate, realistic interpretation possible.

I went got back from a trip to the area recently where I scouted locations and found perfect people for the roles. Most of the plot is based on real things that have happened in real life to each actor and actress.

Filmmaker: Why did you decide to use Kickstarter to fund this project?

L.: I know I have a loyal following of people interested in my photographs and travel journal blog posts from my previous trips. With this Kickstarter project, I hope people believe I can take things one step further, and create this film. I think people donate to get the cool rewards, but they also donate because they like the project, and want to become part of it. Whether you donated $1 or $1000, every single piece is integral in making this thing work.

Filmmaker: How does this project benefit the tribe?

L.: The tribes can benefit in two main ways:

1) There are many “guests” to Ethiopia who are not well versed in the customs and traditions of the locals, and often present them in the wrong way. You can find misleading images and written text all over the internet. Although I am still very much a foreigner, I feel that through my years of experience working in the area, that I have a greater understanding than the average visitor, and connection to many families and villages. Therefore, when we create the film, we will represent them in the most dignified and accurate way possible. I’ve also considered the subjects in the film as “co-creators”, and greatly involved them in the writing process to ensure everything is correct.

Now, many people wrongly condemn these tribes as “backwards” or even “savage” because they do not understand their way of life. They may see them as “simple” because of the way they live. However, what I believe is quite the opposite. These are human beings who have invested their capacity and potential into other areas of life different from ours, but still equal and no less “advanced”. Such a reputation can even lead to certain human rights abuses, such as what is happening in the Omo Valley right now. If you’re interested in further reading, here’s a great collection of articles on the subject.

I want to end this irrational way of thought. Although my film is not necessarily a political call to action, what it does do is bring these people on to the same playing field, and presents them as I would any other “actor” or person with a real life story.

2) Aside from bringing back a great piece of cinema that presents the tribes in a dignified manner, the local community and people will also benefit from this film. Payments and donations directly to the villages and people we work with are one of the largest portions of the budget.

The permit process is paid to the country of Ethiopia, but “local permits” are just as important. During my scout, I sat down with chiefs of the village and negotiated a daily rate for filming in their village. Also, the main people who appear as regulars are also compensated individually. This money is important to the villages, as they can save it for times of drought. The Omo Valley is defined as a semi-arid environment, and is susceptible to drought and severe unpredictable weather. Any additional stream of revenue means their cattle can stay healthy, and their numbers plentiful in times of uncertainty. This is why I actually approve of sustainable tourism in the area, as long as it is done with care and respect. It is the elders job to hold on to the money for safe-keeping, and distribute it when necessary. I trust all the chiefs I am working with for the film, and their entire village is aware of what will happen when the film crew comes to town.

Filmmaker: Would you say the line between photography and film is becoming more and more blurred?

L.: Although I believe photography and film are two completely separate mediums and story-telling devices, yes, I do believe the line is becoming blurred. First of all, the gear we use is having a sort of “marriage.” There are DSLRs that shoot video, and there motion cameras such as the RED which has a high resolution sensor good enough to shoot stills for magazine covers. It’s a fascinating time to do what we do. Secondly, in advertising, I’ve noticed that collaborating stills and motion into one production will eventually become the norm.

Filmmaker: Such as the Killing Lincoln project you just worked on?

L.: Killing Lincoln is the perfect example of the stills/motion collaboration I just described.

I recently had the privilege of collaborating with Variable and photographing the campaign for National Geographic Channel’s feature film Killing Lincoln. My good friends at Variable produced all the promotional video for the TV commercials and I shot the stills for the print advertisements. ??By combining both the advertising photo shoot and the video into one large production, we could work in a more elaborate set and obtain the highest production value possible. This type of collaboration can only work if the photographer and the filmmakers are on the same page. From the production’s early conception, Variable and I were working together with National Geographic on mood boards, lighting references and even the compositions we wanted to include in both the promo videos and photography. Without a collaboration like this, the filmmakers and photographers would work on separate productions. They might try to recreate the same set, or work at different times and obtain visuals that don’t have the same cohesion that you can get when working together. In this case, our collaboration was definitely the best option.

You seem to be doing pretty well for yourself. You’ve enjoyed tremendous success since a very young age. Why not just continue making a comfortable living? Why undertake such a risky project in such a remote and unforgiving area?

I’m a huge advocate of creating personal work, and not just spending your days going from one commissioned advertising assignment to the next. Personal projects help keep your work fresh, and a lot of people have found out about my photography initially through these trips I do, such as the one in Ethiopia. Also, I’m just fascinated with Southern Ethiopia. There’s not much I could do to try to stop myself from going.

As the lines blur between photography and filmmaking, narrative and documentary, we are heading towards an exciting future for filmmaking. I’m not sure if major studios are going to line up to take a risk on funding this project. In the past, that would have made this project nothing more than a dream. The real beauty, is that we live in an incredible time as filmmakers. If you like what you’ve seen and read, with your help, an amazing piece of cinema can be produced. This is the democratization of filmmaking working in the best possible way it can. To find out more about this project and how you can contribute check out the People of The Delta Kickstarter page.