Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes 2013: Gray’s The Immigrant and Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty

The Immigrant

The Immigrant James Gray’s The Immigrant is Classic Hollywood melodrama, done incredibly well, a film that powerfully portrays the emotional journey of a Polish immigrant, Ewa (Marion Cotillard), and her pimp, Bruno (Joaquin Phoenix). It offers a powerful historical account of the connections between the mass immigration to the United States and the often desperate desire to achieve the American Dream, while also serving as a brutal reminder of the ways in which that dream was exploited by people who were willing to take advantage of new arrivals, many of whom were overwhelmed by their new home.

Gray’s film borrows from classical cinema in order to convey the complex emotions felt by many first generation immigrants. The film’s story could have been told in a Marlene Dietrich film in the 1930s: Ewa, freshly arrived on Ellis Island in 1921 from Poland, lines up with thousands of others, the Statue of Liberty standing as a receding promise in the distance, while American flags welcome the new arrivals in the great hallway of Ellis Island, all of which is beautifully captured in the cinematography of Darius Khondji. But upon arriving, her hopes are dashed when she is separated from her sister, who is diagnosed with tuberculosis, and told that she risks deportation because she has been reported as a woman of “low morals” and because the address for her family is “invalid.” But she is soon rescued by the mysterious Bruno, who offers her work — initially he tells her, as a seamstress.

Willful and intelligent Ewa quickly assesses her situation. She has been abandoned by her uncle and lacks any resources and therefore chooses to work for Bruno, not because she likes or trusts him but because he offers what she needs. “I don’t like you,” she tells him at one point. “I hate you, but I like money.” She wants the money not for herself, but to pay to get her sister out of the infirmary so they can start a life together.

The best melodramas introduce complex, often ambivalent, emotional situations, and The Immigrant brings out this complexity in powerful ways, conveying Ewa’s ambivalence about Bruno, who could, within in an instant cruelly assault her verbally and then show incredible tenderness and sympathy. Jeremy Renner, as Bruno’s cousin, Orlando the magician, brings a certain lightness to Ewa’s situation, offering very briefly, a possible alternative fantasy of escape, but also serving as a threat to Bruno, who is jealous of Orlando’s “pretty-boy” looks and his charisma on stage.

The Immigrant also speaks to our current debates about immigration reform. It’s difficult to miss the fact that today’s code words about Latino and Asian immigrants are remarkably similar to those used to describe past waves of new arrivals, including the Polish immigrants like Ewa and her sister, Magda, who are called dirty, lazy, and of low morals. As a result, the film succeeds both on an emotional level and as a means of relating a significant aspect of the American experience.

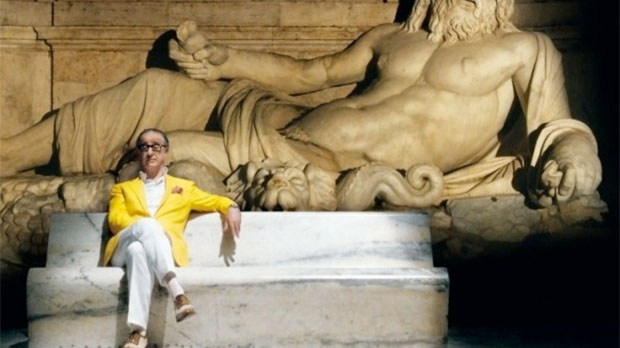

In Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, the weight of thousands of years of artistic, literary, and architectural tradition hangs over the novelist and protagonist, Jep Gambardella, and his coterie of artists, financiers, and high-society revelers. All of this takes place in the shadows of Rome’s most astounding monuments, constantly reminding us — and Jep, who retains an ironic detachment from everything he sees — about the possibility of artistic creation, about the disillusionments that come with aging, about the desire for authentic human connections, and about the profound concerns about the future of Italy itself. It is a sprawling and, in some cases indulgent, film, but one that is also incredibly passionate about cinema — Fellini’s La Dolce Vita is a clear influence — and about the city of Rome, where it is set.

The film works, largely due to the character of Jep, played with a wry sensibility by Toni Servillo, who is the quintessential observer. Several decades earlier, Jep had written a best-selling literary sensation, but rather than continuing to write fiction, he meanders aimlessly from one outrageous party to the next, paying for his decadent lifestyle with newspaper articles where he covers cultural events assigned to him by his editor, including one performance art piece in which a woman runs nude and headfirst into the pillar of one Roman monument, as if to enact a sort of violence against the past and its ability to suffocate the possibility of originality. Many of these events have an almost mechanical quality, as if the participants are going through the motions of celebrating anything in particular. He repeatedly considers writing another novel, but doesn’t seem to have the energy for it, and isn’t sure what he would say.

This extended sense of ennui is set against the backdrop of some of most fabulous settings in Rome. Jep’s apartment overlooks the Colesseum in Rome, and other landmarks, stunningly shot by Luca Bigazzi, make their cameos throughout the film, but these objects seem to contribute to Jep’s — and the film’s — lack of direction. Due to this uncertainty, The Great Beauty sometimes feels longer than it’s relatively long running time, but it is a journey worth following, even if it remains unclear where it will take us. Toward the end of the film, Jep is provided with at least one alternative to the cynicism that he harbors, although it is unclear whether he will — or can — take this path.