Back to selection

Back to selection

No Clean Getaways: Amat Escalante on Heli

Heli

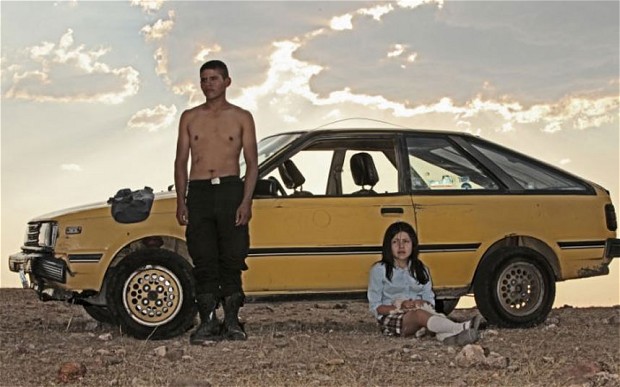

Heli It starts with a slow tilt over dead bodies traveling in space, slowly revealed to be tucked into the back of a white pick-up truck. One of them will soon be hung from a bridge, the early morning light silhouetting the dangling body: its formal sleekness notwithstanding, Heli isn’t for the faint of heart. Soon we’re introduced to a small, modest family in a remote Mexican village: a father and his two children, one of whom has a child of his own from a young wife. Surrounded by desert and not too far from the auto plant which employs many of the local men, the title character of Amat Escalante’s revelatory breakthrough film is caught in a vise not of his own making. His sister foolishly allows an older man she’s seeing, a cadet in the sadistic local police force, to stash cocaine in the water tank above their house. She doesn’t ask where it comes from, why he wants to put it there or who, if anyone, would want it back. Predictably gruesome consequences visit everyone involved, shedding light on the rampant corruption and moral catastrophe at the root of Mexico’s increasingly bloody drug violence.

When he first came to Cannes with his debut feature Sangre in 2005, Amat Escalante wasn’t a household name amongst cinephiles. His second feature, 2008’s Los Bastardos, was well received at Rotterdam but never found its way stateside. But after winning the best director prize in last year’s Cannes competition for this, his third feature film, to say his profile is rising would be an understatement. The 35-year-old, a protege of Mexican wunderkind Carlos Reygadas, chatted with Filmmaker recently about his unusual method and the burdens of drug violence for Mexicans.

Heli opens in New York and Los Angeles tomorrow.

Filmmaker: Have you personally had to reckon with the violence in Mexico due to the drug trade?

Escalante: There’s been occasions where on the phone — everybody receives these phone threats, kidnapping threats, stuff like that. That’s kind of a common occurrence. Besides that, just seeing it from far away or in the news or knowing of people that have had something happen to them. That’s basically something that everybody has to deal with. Luckily I haven’t personally suffered anybody near me being kidnapped or beheaded or stuff like that. But it’s there and it’s all over the place. A lot of the things in the film come from the news near where I live and Mexico in general. There’s nothing in the movie that’s invented or that I came up with really. It was about putting together a story of this family and this character using all the elements that were out there.

Filmmaker: Once you had decided to tell this tale, how long did it take you and your co-writer to get it to a point where you thought you were ready to go off and try to get it made?

Escalante: For two years I wrote on my own and then two more years with Gabriel Reyes. It changed a lot from the beginning. We never really set out to do a movie about drug trafficking, it was more about a family that lived in a certain region and our interest in seeing what happened to them with the situation around them unraveling. A lot of the inspiration came from wanting to make a movie about families that came to live near a General Motors plant near where I live. It used to be the countryside and then it became dominated by small towns around this factory. I wanted to tell the story of a family that worked there and see how they would be affected by all the corruption and injustice that was going around that area.

Filmmaker: The movie rarely employs anything that I would refer to as traditional coverage. What were the artistic or aesthetic imperatives that informed how you and your cinematographer chose to tell the story?

Escalante: I always tried to do more conventional set-ups so I could edit the movie more conventionally. But usually I end up not liking them! For some reason I always go for another way of shooting things that’s a bit more off the chart per se of what you’re supposed to do, not so orthodox. I think that’s how we approached it. Not on purpose but just that’s the way I wanted to see things. That’s how we shot it. I remember the first couple of days we tried to shoot coverage like a regular movie, and I wasn’t feeling comfortable with it. When I tried to edit those things they didn’t come out either. So I tried to just do it the way that I feel it. I always tried to make it as close to conventional as I can. It’s not that easy for me!

Filmmaker: Were you ever nervous, shooting scenes in long takes or shooting scenes in one shot that move and ask a lot of the performers and of the audience?

Escalante: I shot a lot of footage. It was the first movie I did digitally and the script was long and we shot a lot of stuff, around 70 hours of footage on a Alexa. So it was the first time that I shot so much material and I knew that it was going to be better to have more than to have less. It was difficult at the same to shoot so much and to do so many takes, but for me I felt it was necessary. Since I don’t rehearse and I don’t even show them the script, the actors, each take we do is kind of an exploration in a way.

The more shots that I can shoot, the more takes I can do, the better. So in that way that’s good, but it’s also more difficult when you shoot so much and time runs out and you need to stop. I have to stop shooting at some point because I have to rewrite the script, because we’re running out of time, etc. But for me it was worth it just to be able to get those scenes that maybe seem difficult or more complicated, especially for non-actors, to do.

Filmmaker: So the actors were unaware of the script? They did not know the end of the tale that they were performing in while you were with them?

Escalante: No, no. They had some idea. It wasn’t like a super top secret or anything, the script was around there, but for me and for the DP and people like that. It wasn’t something that was in the hands of the actors. They never read it or anything. I just told them before when I was confirming if they were gonna be in the movie, I would give them a list with all of the difficult things that they would have to do, and then they will decide if they want to do it or not. If anyone needs convincing they’re probably not going to end up doing it once we’re shooting.

Filmmaker: What were your criteria for selecting the cast and did that condition make it difficult to find the people you wanted?

Escalante: It was kind of difficult. When I wrote the script I didn’t know who or how — I don’t think of how the character’s going to be physically and stuff. Or even their attitude so much, I just kind of write those characters that say these things and then when I find people that I am attracted to, I make them fill the void that I created in the script. And for them to not become somebody I wrote or thought about is key. I want the person that I got to fill the void of the script that I made for them.

In this way I change a lot of the dialogue. I go over it with them before each scene and once I know how they are doing, I even interchange some parts of the script. So I make my story and my characters fit the people that I find. They stay whoever they are. I just put them in my script and that’s what I’ve done so far. I like it. It’s kind of an exciting way of doing things. Because of the budget not being so high or it not being a Hollywood movie, one can do those kind of crazy things, take those risks.

Filmmaker: Was there anything that surprised you about the nature of the film you were making as you were making it in terms of the tone of the movie or certain aspects of the narrative that were more important than you initially had conceived them to be? Or various things your actors were giving you that you didn’t know they were capable of?

Escalante: Andrea Vergara played the young sister of Heli. She was very intelligent and she was able to do stuff that I wasn’t expecting anybody to be able to do that wasn’t a professional trained actor. So in that way I was able to do more dramatic scenes sometimes or more complicated scenes that I thought we were not going to be able to do because she had a very good memory and she could cry on cue. So in that way, it was good luck finding her. I wasn’t so clear what kind of movie I was making really. When you’re just trying to do each shot, each thing the best way that you can and be true to yourself and try to keep a certain coherence to the movie that you’re making and the world that you’re trying to create, everything can fall into place.

I know that in the editing process I’m going to again rewrite the whole movie in that way, especially since I shot so much footage. So I was just shooting the scenes the best way possible and then knowing that we’re getting them the best way and letting life also kind of invade the movie with improvised things or accidents. That was basically what I was focused on, and telling a coherent, or at least somewhat coherent story that I knew I could fix or amend in the editing.

Filmmaker: Do you think that this is a crisis that Mexico is going to be able to see its way through in the short term?

Escalante: The film is all full of very young people, of children and babies and young people. I think that’s the hope that there will be in Mexico. If we want things to get better I think we have to start at the root, which is protecting the young people, educating them, not letting them get pregnant so young, making abortion legal for example. Those elements would then fix the future. Otherwise it’s kind of difficult to get over the situation, I think. And, yeah, that’s why the movie also has that element of young hope and it ends with that.