Back to selection

Back to selection

Charting the Course: Data Visualization in Documentary Film

Mission Blue (Photo courtesy of Icarus Arts & Entertainment)

Mission Blue (Photo courtesy of Icarus Arts & Entertainment) “Every single pixel should testify directly to content.” So says Edward Tufte, a professor emeritus at Yale and pioneer in the field of data visualization. And if this emphasis on clarity and, essentially, story is true in the world of static infographics, it’s exponentially so when content comes at 24 frames per second.

In the short PBS film The Art of Data Visualization, Tufte reaches far back in time, before the mundane pie charts and bar graphs that school children are taught to decipher, finding the beginnings of data visualization in stone-age cartography and the rise of science during the Enlightenment. Exhibit A: Galileo’s tracking of sunspots over several weeks, transforming his observations into beautiful engravings that visualized the information for all to see and understand.

Jump forward 300 or so years, and nonfiction filmmakers began to use graphics and visualizations to convey information too difficult to explain by words alone. It was no accident that John Grierson sought out animators as well as documentarians when he started the National Film Board of Canada, resulting in visually startling films — with huge amounts of information — like Cosmic Zoom (1968) and Universe (1960). Early American films like The Plow that Broke the Plains and Frank Capra’s Why We Fight series, with animation by the folks at Disney, used maps, graphs and even faux newspaper headlines to quickly convey complex information.

In recent years tools like After Effects, Photoshop and Illustrator have brought documentary graphics out of the world of traditional animation and into a specialized field all its own — though with obvious parallels with graphics-heavy television commercials and feature-film title sequences. And polished graphics can make all the difference in giving a film professional polish. Morgan Spurlock credited his animators on Super Size Me, which was shot on a 3-chip Mini-DV camera, with preventing the film from feeling like an amateur “video movie.”

With popular websites like 538 and Vox popularizing a data-driven style of news, documentarians today are being charged with incorporating statistics, flow-charts and graphs, all in compelling, visually seductive ways. The subject matter of films like Inequality for All, The Internet’s Own Boy, DamNation, Maidentrip and Cinelan’s online We the Economy series have demanded not just inter-titles and lower thirds but full-blown onscreen graphics. Joshua Ligairi, founder of Icarus Arts & Entertainment, explains, “Obviously, as filmmakers we’d like to be in a position where we have visuals or characters strong enough — and a story simple enough — that our meanings can be communicated more cinematically. But the reality is that many of the stories we tell in nonfiction necessitate the communication of a huge amount of information just to get going.”

This was the case with his 2009 film Cleanflix, co-directed with Andrew James. The directors found their rough cut 20 minutes longer than desired, due in large part to relying on the film’s characters to convey needed exposition. “At one point in the editing process, we decided that whenever we came to a big informational chunk, we’d really take control of the story and use a combination of text and b-roll to get us from point A to point B and then use supplemental footage of our interviewees to support what we’d communicated.”

“[Data visualization] can not only act as supporting content but can drive the overall story and provide succinct clarity,” says designer Jeff Soyk, who worked on the Peabody-winning interactive doc Hollow (directed by former Filmmaker 25 New Face Elaine McMillion Sheldon). “The challenge in generating these graphics is contextualizing them, designing them and making sure they play an appropriate role in propelling the story forward.”

Planning it Out

So where to begin? Directors and producers working on a film that might benefit from even minimal data visualization ought to first talk with animators and graphic designers, considering these collaborators as essential a component of the crew as the cinematographer or editor. A great part of this process may depend on your budget, but top-notch designers can be found at large companies that generally do fiction film special effects or at smaller firms that specialize in graphic design, titles and infographics (often for print and Web-based media). Or, they can be freelancers working on their own. When Jon Reiss was producing his original graffiti documentary Bomb It in 2007 (and its sequel Bomb It 2 in 2013), he says, “I essentially crowd-sourced a number of up-and-coming animators, mostly coming out of various schools in Los Angeles.” This approach not only netted Reiss a large group of hungry talent, but also matched the street-art ethos of his film — along with creating significant savings for the production budget. Beau DeSilva, one of these artists, says, “When I worked on the graphics for Bomb It, I approached the project with a love for graffiti art, being that I was an avid graffiti artist at the time. With a degree in three-dimensional animation and broadcast design, I couldn’t wait to integrate my passion for the two artistic mediums.” Today DeSilva is an Emmy-winning lead broadcast designer and art director at the NFL Network.

Nico Puertollano, a designer who founded Flux Design Labs in the Philippines and now also owns the firm Native to Noise in New York City, emphasizes the importance of copious amounts of dialogue and multiple iterations of a design concept; this communication has been key to creating the graphics for all three seasons of Morgan Spurlock’s Inside Man. “We collaborate to find out what the filmmakers really want to say, and we will find out how to visualize that in a clear manner. With Warrior Poets, Morgan Spurlock’s production company, we would get a script, and they would ask us to visualize that section. Then we ask our questions to make sure we got the concept right. And there are times we would help in rewriting that part of the script to make it tighter.”

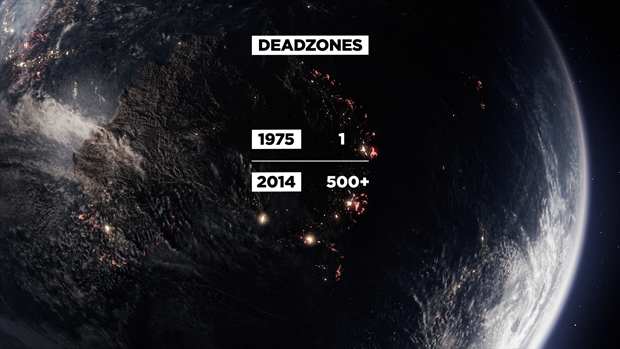

Trust and enthusiasm can be just as key as communication. Marc Smith, who came with a wealth of design experience from his native New Zealand, has now worked for almost three years for the New York branch of Framestore, a multinational company known primarily for its VFX work for films like Guardians of the Galaxy. He recently created the data visualizations for Mission Blue, an environmental documentary co-directed by Robert Nixon and Fisher Stevens now showing exclusively on Netflix. “From my very first meeting with Fisher,” Smith says, “I was inspired by his enthusiasm and passion for this story that needed to be told. It was infectious. I presented a range of styleframes and references to review shortly afterwards, and it became immediately apparent we were on the same page creatively. This led to a culture of trust, the ‘holy grail’ of design projects, where the designer is allowed enough room to create freely without the limitations often imposed in traditional advertising, for example, involving huge chains of command and approval processes.”

When it comes down to specifics, perhaps the most important decisions regarding graphics are where they will go and what information they will convey. The foremost concern here is to have good information. As Tufte says: “First it has to be true. Great visualizations are a byproduct of the truth and goodness of the information.” The work of obtaining accuracy is done with a researcher or by the writer or director personally, but a dialogue with the designer can help determine where to place graphics, a process akin to a drawn-out spotting session with a composer. As Puertollano says, “I really believe that if the design looks great but does nothing for the film, it’s best to adjust it to have relevance to the film as a whole and not just be a cool graphic in the film.”

One overriding requirement for any type of film is that the visualizations not distract from the story. Maggie Bowman is the producer of Hard Earned, an upcoming six-hour film by Kartemquin Films about the working poor. It’s a verité film, in the tradition of much of Kartemquin’s best-known work, but it tackles a social issue with complex data. “The primary drivers of the narrative are scenes with the subjects themselves,” she says, “but we are using infographics at select points in the story to connect our subjects’ struggles to larger national trends. The challenge has been to integrate data points into the story, both visually and narratively, in a way that doesn’t pull the viewer out of the emotion of the scene. We started with a really research-intensive phase, working with subject experts, to find those data points that would best accent the subjects’ struggles. We’ve been working with Mode Project in Chicago to establish a visual language that feels really organic to our stories. And now we’re taking each data point and going through numerous rounds to experiment with how to visually convey the data in a way that a viewer can quickly grasp. And once again, the goal is to add to the emotion of the scene, not pull the viewer out of it.”

Creating the Look

After placing the data visualizations and determining what their content should be, comes, of course, the actual designing, which is often a collaboration between a director and designer. As Soyk says, “A filmmaker and designer should always discuss the themes at play, any historical significance to consider, visual cues observed in footage and the main goals of a design and its role in a scene or the overarching story arc. And even beyond choices in line weight, color and typeface, the choreography of animated motion is imperative in creating a well-executed visualization that flows with the piece and presents content in a digestible and nondistracting fashion.”

There’s a lot to consider, covering everything from serifs to full-screen composition. The fundamental rule, following Apple designer Jony Ive’s rule of thumb to just get design out of the way, is that any successful graphic must relate back into the film by telling a story and present complex data in a quickly understandable way. All subsequent decisions are based on this premise. Dan Sharkey, owner of the design firm Dizzy Giant, has been working on documentaries for years, most recently Steve James’s Roger Ebert film Life Itself. He works with a variety of filmmakers and says they often “know what they want, but not how it should look. It’s our job to turn a piece of graphical information into something that is functional and visually interesting, but doesn’t take you out of the film. Our graphics should always feel like part of the movie, not a break from it.” DeSilva seconds this — “It’s important that the design style fits the content or subject of the movie,” he says — but adds that there are other basic guidelines, such as that an animation have a contemporary style to make the graphics feel as confident and professional as the rest of the film.

Usually the film’s subject dictates how the graphics should look, sometimes in very obvious ways, like the theme of water for Smith’s work on Mission Blue. “There were a number of instances throughout the film where water provided a reference base for the graphics, perhaps none more so than in the main title itself. We knew from our conversations with the editor that the Mission Blue main title graphic was to appear over this gorgeous underwater footage, with god-rays beaming through the ocean’s surface, after the camera has just panned up from a breathtaking shot of a whale shark moving off into the distance. I wanted to create a sense of loss at the end of this shot with our title reveal. Very literally, as the film itself illustrates, the oceans and this beautiful wildlife are being encroached on and ultimately blacked out. I opted for a somber, unembellished approach that saw the frame shrinking to slowly form the text, before shrinking to full darkness.”

Inspiration can be found in content even when it isn’t as obvious as this. In Rebel, María Agui Carter’s historical documentary about Loreta Velazquez, a woman who served in the Confederate Army before becoming a Union spy, the filmmakers had almost nothing to go on visually except hundreds of pages of written material from the 1800s. “I had maps, letters, diaries and Loreta’s 600-page memoir but only one unauthenticated photograph of her,” Agui Carter says. “Animation and graphics help breathe life and motion into static archival documents, not only by highlighting passages, but by creatively enhancing a point or emphasizing meaning. We shot our own ‘archival’ photographs and montages that my motion graphics team Alisa Placas and Aaron Nee animated so brilliantly.” These graphics were woven in with other archival photos and historical reenactments to create the film’s visual tapestry. “To emphasize Loreta’s first-person viewpoint from her memoir, we animated text from her memoirs and layered it with our footage. Animation and graphics, along with dramatic scenes, allowed me to make a feature documentary about a woman for whom I had only one photo.”

This approach can work even when your subject is right in front of you. With Life Itself, Steve James faced the challenge of interviewing Roger Ebert, who had lost his voice years earlier and was in failing health during production. The solution was to communicate with Ebert via emails, a potentially banal visual element until Sharkey’s team at Dizzy Giant animated and layered them on top of video footage. This was far less complicated than some of Sharkey’s other animations — such as explaining the Mayan calendar for 2012: The Beginning or creating family trees for two different films, The House of Suh and In the Family — but just as effective. The result, in fact, is simple and elegant, a textbook case of getting design out of the way and letting the audience focus on Ebert’s message.

Challenges

If all of this were not challenging enough, there are other challenges that can impede good design. As with other components of an independent documentary, budget is foremost among them. But while animators and designers may be used to working on high-paying commercial projects, documentaries can be labors of love. Smith describes his relationship to Mission Blue in this way, saying that he and his crew care deeply about the film’s subject matter — the preservation of the marine environment. “The people engaged on these projects bring so much more of themselves to the table, without the constraints that money often dictates. The team here worked tirelessly, volunteering late nights and weekends to create something we are very proud to be associated with.” Lack of funds can also inspire lateral thinking and more efficient use of what resources the team is afforded; this, of course, is where a director or producer’s enthusiasm can be paramount for fostering a group vision.

Another less obvious challenge lies in the task of anticipating trends and styles and making a film’s work stand out from other similar projects. Ligairi found this to be particularly troubling on several of his films. “Honestly, for me,” he says, “the biggest thing I think about now is trying to find something organic to the style of the film, but also something that won’t be completely outdated by the time you get your film on the screen. That can be a real challenge with nonfiction if you are following a story as it unravels.” Shepard Fairey had originally agreed to create the poster for Cleanflix, a doc about film censorship in conservative Utah, but he became unavailable after his Obama “Hope” poster hit the stratosphere. Ligairi’s two designers worked to complete the film in Fairey’s style, but, as Ligairi says, “by the time the film actually came out, that style felt pretty tired.” But given documentaries’ long production times, sometimes it’s impossible to anticipate trends. “We went with 3-D title cards integrated into real environments for a recent film called Plan 241. I hadn’t seen it in any feature docs and it still felt fresh and exciting to me as we started post. Now? Overdone. I have to decide if we are going to stick with it or not. I like it, it feels organic, so my gut reaction is to stick with it — but I also don’t want to regret it later.”

One final challenge is equal parts opportunity: the rising prominence of online interactive documentaries that invite viewers to manipulate and explore graphics along with the rest of the film. In that case, individual graphics can be denser; they’re not limited by the temporal pressure to scan immediately that visualizations in traditional films have. Thus they can be more akin to print or Web graphics that contain multiple data points or even multiple graphs, maps or charts simultaneously. At the same time, however, they require greater attention to how users may wish to manipulate them and how to convey navigation — not just information — clearly. Soyk confronted these issues on his work with Hollow, a film about poverty in rural West Virginia that primarily navigates through a vertical scroll on a Web page but which also allows multiple ways for viewers to probe deeper into individual subject’s lives. “For the media-maker,” Soyk says, “the opportunity for a user to explore at will as well as dig deeper into content of greater interest not only requires an eye for visual design and a feel for timed animation, but an understanding of effective usability and content organization that reveals important story content as a user interacts, provides easy access to information of interest to any given user and encourages participation when required.” Many of the innovations in the next few years will surely come in the field of interactive films.

But Soyk also adds a caveat that’s true of all films, interactive or not. “Knowing when to and when not to use infographics is part of the challenge, but knowing their strengths and weaknesses can be key to expressing certain ideas in an effective manner. I see even the simplest of design elements as very powerful components to any project, especially when they genuinely recognize and respond to the core characteristics and goals of a story.” And to that end, any data visualization that moves a story forward is probably a successful data visualization. Far from the clunky blocks of text and figures that could send a film’s narrative to a crashing halt, good graphics are now an integral tool in the story-minded documentarian’s kit.