Back to selection

Back to selection

Tribeca 2015 Critic’s Notebook: Live from New York, Ludacris, The Survivalist, Crocodile Gennadiy and More

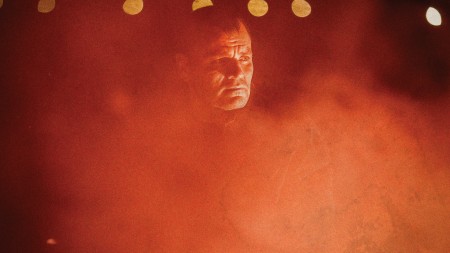

The Survivalist

The Survivalist The Tribeca Film Festival isn’t going away. The 47 people who care about the lives and deaths of film festivals ask the same question every year: Is this brash upstart turned middle-aged guy relevant? The national news media seems, well, not to care. In the film media, all anyone talked about the day after opening night was the unveiling of the Star Wars trailer and the Cannes lineup. But while Tribeca will never represent the pinnacle of Hollywood commerce or European high art in the way the Star Wars and Cannes brands do, its selections and sensibilities do their best to merge the qualities of each with something resembling satisfying results.

The newest iteration opened Wednesday night at the Beacon Theatre in the Upper West Side, far from the environs it supposedly reps with the “T” in its acronym. Robert DeNiro and his right-hand woman, Jane Rosenthal, came out to greet the packed house of fat, mildly bored-looking, mostly white men in expensive suits and the svelte, strapless dress-wearing women who hang with them. Then they rolled the flick, first-timer Bao Nguyen’s Saturday Night Live documentary Live from New York! The audience ate it up, laughter spilling from the aisles. A hearty applause greeted its conclusion. For a festival that is constantly flouting its essential New York-ness, it couldn’t have found a more appropriate opener.

But the cracks in the facade still showed. Some people complained the film was too long. Others, your author included, thought it was bizarre that Ralph Nader is in the film more than Eddie Murphy. Or that Nguyen’s film bends over backwards to trumpet how groundbreakingly progressive SNL has been at the same time that it slights the thing for not knowing what to do with Garrett Morris (a black man!) in its earliest years or, for much of its run, not treating its female cast members with respect. Made with the full support of Lorne Michaels and many of the show’s biggest stars (Chevy Chase and Will Ferrell, Tina Fey and Dana Carvey sit down for candid interviews) it’s an inside job; hagiography, albeit fun, is the unsurprising result.

It was later that things got weird. Last year, Tribeca hosted its opening night at the Beacon for the first time. The Madison Square Garden company bought fifty percent of the festival before the 2014 edition, and the Beacon is one of its properties. Would James Dolan sink Tribeca like he has the Knicks? Whispers flew about of impending changes. Things stayed more or less the same from the programming and organization side, however; the most significant change was that the festival suddenly felt it had to put on a rap concert after the first movie to get people’s attention.

Last year’s leadoff rap concert worked perfectly. Time is Illmatic, an alluringly modest documentary about Nas’ rise to rap superstardom, got things started before the man of the hour donned the stage to preform his seminal debut album in its entirety. I was sitting near the front of the majestic, 90-year-old theater that night, and it was easy to get lost in the revelry. Tribeca’s second attempt at rap concert organizing fell flat on its face. Ludacris, whose sell-by date seems to have passed sometime in 2006, was at one time a host of and performer on Saturday Night Live. Hell if anyone at the Beacon remembered that. He didn’t have any business being there. No one on earth associates him with Saturday Night Live. It was the single most depressingly unhip rap concert I have ever been to. It was so bogus; I heard people under 30 complain that they didn’t book Paul Simon instead.

The rapper came out in a yellow and grey shirt, flexing his brand of gentle narcissism, his expertise of the humble brag clearly not flagging with his record sales. I was seated in the middle section of the orchestra, right on the aisle. Looking all around me, I saw most people were holding up phones even though they were too far away to get a good shot. Those same portly white dudes in high-class threads, half smiles on their disconcerted faces, knew not what to do. Their dates forced some enthusiasm, throwing their hands up in the air when Ludicris asked, even if the most staid in the crowd looked on with confusion, hands about shoulder height, as if surrendering to a stick up, reverting to the stock pose they give when encountering men of Ludacris’ general age, ethnicity and appearance saying the same phrase on these not-so-mean-anymore Manhattan streets. If anything represented the once-revolutionary tinge of hip-hop having given way to the crass dash of corporate capitalism, it was this room and this moment. So I headed for Tavern on the Green to get my New York old-money vibe going, even in the 15 dollar, neon-colored Champion sneakers I bought in a Cincinnati Payless.

Biting its style from the New York Film Festival, the Opening Night party wasn’t at some nondescript Times Square or Chelsea night club, as its been in recent years. The 80-year-old Tavern on the Green, a regular hangout of Central Park West’s most dynamic movers and shakers and always the home of NYFF’s annual prom, played host. DeNiro and his wife held court at a table within the restaurant’s glass-encased central dining room, his bodyguards not far from either end, notable passersby such as scumbag-in-chief Rudy Guiliani and SNL honcho Lorne Michaels paying their respects. Young celebrities like The Knick’s Andre Holland or Precious’ Gabourney Sadibe enjoyed sponsored gin or prosecco, while goofy film journalists and industry lackeys took self-consciously ridiculous photos at the 3D photo booth, one that spit out a rotating GIF of the attendees against the backdrop of a Tribeca red carpet with far more hoopla and onlookers than the real thing had provided just hours before.

Regardless, TriBeCa has come home now, sort of, with a better reputation than it’s ever had. DeNiro’s magic solution to the post-9/11 downtown economy has avoided the neighborhood whose name it bore like the plague for about half of its existence. Screenings moved away from the Regal Battery Park in 2007, and the festival was derisively called the “Union Square Film Festival” by those observers who could see 30 movies and attend 12 parties in 10 days but never once set foot in Tribeca. But with the opening of Spring Studios on Varick Street, just south of the Tribeca Enterprises and Tribeca Film Institute headquarters, the hub of the festival is now once again in the neighborhood for which it was named. The Regal Battery Park, the biggest multiplex south of Canal Street and the closest one in walking proximity from TriBeCa, has retaken its place as the preeminent venue. Some pizzeria on Fulton will surely sell its first slice to a Tribeca Film Festival attendee in many years, and now, thanks to the inflated prices one finds for nearly every good and service in this borough, the economic stimulus can really begin!

Autism in Love, a profile of the two couples and one lonely man who are all on various parts of the autism spectrum, was among the first films Tribeca screened for the public on its second day. It wasn’t a hot ticket, this movie about developmentally-challenged adults in a just-after-work Thursday evening slot. Directed by Matt Fuller, it’s the type of gentle verite portrait of an underreported topic that isn’t going to alienate anyone. The film benefits greatly from the fact that the subjects are, in large part due to their developmental issues, remarkably candid about the burdens of love, loss and compromise within their various relationships. Whether it is their mental faculties or their collaboration with the director that led to such moments seems largely beside the point, for Autism in Love is an affecting and effective film, but it hasn’t yet stopped bothering me either.

Autism in Love intercuts segments about its five subjects. There is Lenny, a Lakers-jersey-wearing teenager, desperate for a girlfriend while living with his single mother; Stephen, whose autism has kept him child-like deep into middle age; Stephen’s wife, Gita, who has been diagnosed with terminal ovarian cancer; and Lindsey and Dave, a thirtysomething autistic couple who, after eight years together, are flirting with marriage. These folks share the same struggles anybody searching for or hoping to maintain intimacy does. Trust and commitment, illness and economics are explored in Fuller’s film during long takes that don’t feel staged necessarily but have clearly been shaped to some extent by the filmmakers, who often resort to coverage and narrative cutting techniques in a way that suggests a level of control true verite rarely exhibits.

The same could be said of another film I caught later that evening, Crocodile Gennadiy. It’s a profile of Ukraine pastor Gennadiy Mokhnenko, who came to prominence in the early part of the aughts running a home for homeless and drug-addicted children in Mariupol — one that forcibly abducted the children in order to put them on the straight and narrow. Outfitted with capitalist training wheels and suffering the wake of de-Sovietization, the country overrun with kids doing an often lethal cocktail of injected cold medicine and alcohol, the charismatic Mokhnenko’s tactics first drew the ire of the local government. But as we see in Steve Hoover’s wistfully beautiful film, executive produced by Terrence Malick, they’ve come to underwrite his Pilgrim Republic rehabilitation center. As Ukraine comes apart at the seams as a populist movement to oust former President/stooge for the Russians Viktor Yanukovych gains steam and the Russians come to the aid of their proxy, we see Mokhnenko doggedly continue his work ministering to women in prison, shaking down pharmacies that sell illegal narcotics and counseling both abusers and the abused, the violent and the docile. In one bravura sequence, he saves an invalid woman from the man who kidnapped and repeatedly raped her before, in an act of Christian charity, sparing the man the beating everyone in the audience thinks he deserves and Mokhnenko is surely capable of delivering.

I’m still not sure what Hoover would have us make of Mokhnenko; tall, well-built and square-jawed, he’s a cartoon character of Slavic toughness. His youthful energy and curiosity shine through in the footage, but his brand of moralizing conservatism is always just the edge of a sword away from totalitarianism, even as he doesn’t share his elders yearning for a return to Communism. His no-nonsense approach, as unseemly as some aspects of it are, has done its fair share of good for people trying to crawl out of the depths of dopefiend-dom. Like Autism in Love, and probably most of the other docs at the Tribeca Film Festival, the movie overuses its score. But the disarming interludes of Mokhnenko hanging out with his own kids, shaving, eating hot dogs (his favorite “western technology”) and general philosophizing about makes him hard not to root for and certainly very difficult to forget, even if I wonder what hand he had in shaping the material.

The Survivalist had its world premiere toward the end of the first full evening of public screenings. It sent me back out into the Battery Park night two hours later in something of a daze, its chilly atmospherics and overwhelming sense of gloom hard to shake as I strolled along the Hudson river. A tense, post-apocalyptic British/Irish co-production about a man who has just buried his brother and only companion in the forest during an especially lean year well into some kind of peak-oil inspired civilizational death spiral, it was an inspired beginning to my fiction film consumption. The title character, played by Martin McCann in shades of taciturn longing and barely concealed paranoia, runs a small farm where he masturbates to photos of an old lover and grows just enough food to get by, although the constant threat of marauders is no joke. When white-maned Kathryn (a marvelous Olwen Fouéré) and her tall, nubile daughter Milja (Mia Goth) emerge from the forest, offering seeds to grow legumes in exchange for shelter and sex, our man’s armor doesn’t go down one lick. But over the course of this broodingly lensed, excruciatingly frank look at life in the end times, emotional barriers slowly collapse even as trust remains elusive. After a particularly brutal raid leaves them with little food, however, the survival instinct begins to create fissures in the most seemingly unbreakable of bonds. The movie plays like Claire Denis riffing on Connor Horgan’s One Hundred Mornings, another low-budget Irish effort that tackled the thorny, hard-to-stomach sexual exigencies that the end of the world always ends up presenting. Here’s hoping some gutsy distributor takes a chance on this one; director Stephen Fingleton, making his directorial debut, is a startling new talent.

As is the custom at Tribeca, the more star-laden premieres of higher-profile narratives and Oscar-courting docs began to emerge on the festival’s first Friday night. Franny, by Andrew Renzi, is one such title. Renzi has built a strong reputation for himself as a young producer on the come and a director of thoughtful experiments, such as last year’s Tribeca entry Fishtail. His new film is a much more accessible and straightforward narrative, the type of well-made if completely unnecessary thing that was churned out with regularity by the studios in decades past and has been relegated to Indiewood since around the turn of the century. In a pre-credit sequence accident that happens five years before the narrative proper begins, Gere’s title character accidently distracts his best friend (Dylan Baker) from the road just as a truck barrels into the intersection they are crossing.

The massive accident leaves the friend and his wife dead, and the rest of the movie is about Franny’s struggle for atonement as the deceased couple’s daughter (Dakota Fanning) returns to Philadelphia with her medical school indebted fiancee (Theo James). As Franny insinuates himself into their life with unprovoked acts of largesse, this wealthy, prescription drug addict lout starts to awaken from his fog, but not without unexpected consequences for himself and everyone else in his sphere. Played with hammy but generally amusing chutzpah by Gere, the film is full of fine, unfussy thesping. While its narrative never surprises you (things more or less work out for everyone involved) or grips you in a way a bleaker and less traditional film might have, it is an effective display of strong craftsmanship across the board, light years ahead of the type of star-studded dud this festival used to constantly run during its nadir in the second Bush administration.

Men Go To Battle, which despite its lack of household names, was another Tribeca selection buzzed about before the festival. The New Yorker weighed in pre-fest to suggest that Zachary Treitz’s largely conflict-averse, oddly weightless movie, set on the dawn of the Civil War, is an “instant classic western.” This critic has never known anyone in the Bluegrass state who has considered the place as “The West” in any way, shape or form, but that may be beside the point. As gently poetic and funny as the movie is some of the time, its aimless narrative of two brothers in 1861 Kentucky, one of whom ends up marching with and, well, sort of fighting, for the Union, felt like a slap in the face. Their lives of backwood, slave-less farm labor are portrayed as some sort of simulation of down-home merriment; Treitz’s Small’s Corner, Kentucky isn’t ever graced with any urgency or relevance, and the movie quite deliberately frustrates the viewer, at least one who expects even the thinnest pretense of story infused with something resembling meaning and verisimilitude.

It’s such a waste; this movie has a remarkably potent neo-Dardenne Brothers visual style, all long-center punched close-up tracking shots, and the production values are simply stunning given what was surely a low budget. But historical pageantry isn’t art. Co-written by Treitz and his muse, indie doyenne Kate Lyn Sheil, whose ghostly period vibe largely goes to waste here as well, Men Go To Battle feels like a stunt by people who aren’t very invested in the legacy of the era, New Yorkers who are much more interested in seeing Will Oldham don Confederate gear (why one of our Kentucky-bred heroes ends up marching with the Union is never explained adequately) and hanging out with Civil War reenacters than approaching their subject matter with authenticity and wisdom. The mixed bag of period-inappropriate dialogue and temperaments on top of the absent narrative make this feel like somthing of a first: a stylized, Civil War-period mumblecore gone awry. In the match-up of movies set on the farms of brothers in eras of unrest, The Survivalist wins by a country mile.