Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“If You Read the Script You’re Not Gonna Want to Do the Movie”: Mark L. Lester on Commando

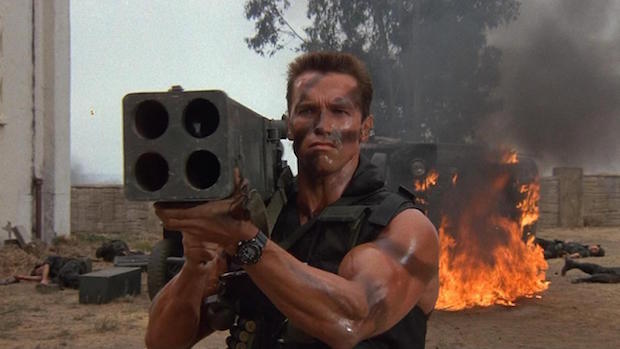

Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando

Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando Thirty years ago this month, director Mark L. Lester changed the course of action cinema forever when he solidified Arnold Schwarzenegger’s persona in the gloriously excessive Commando. Schwarzenegger was already a star thanks to the Conans and The Terminator, but Commando is the film that established the identity he would revisit in film after film – and that introduced the “bigger is better” combination of exaggerated action and comedy that producer Joel Silver would apply to his Lethal Weapon, Die Hard, and Predator series, among many other pictures. Those movies would be heavily influenced by Commando’s vivid palette and precise attention to cinematic space and geography, both of which stand in stark opposition to the style one finds in more recent action films like the desaturated, frenetically edited Bourne movies (or the desaturated, frenetically edited, Joel Silver-less A Good Day to Die Hard). Commando has aged exceptionally well thanks to the clarity of Lester’s compositions and cutting as well as the pre-CGI effectiveness of its convincing stunts and action set pieces; the movie is energetic and exhilirating but not exhausting in the manner of so many recent tent poles, where the actors and action are suffocated by computerized visual design.

Lester himself is a fascinating figure, a successful independent filmmaker in the ’70s who transitioned from exploitation pictures like Truck Stop Women and the cult classic Class of 1984 to high profile studio assignments such as Commando and the Stephen King adaptation Firestarter. Yet practically as soon as he found success in the studio system, Lester went back to the independent realm as both a director and mogul, forming his own distribution company, American World Pictures, in 1992. On the occasion of Commando’s 30th anniversary, I sat down with Lester to ask him about the making of a contemporary action landmark as well as his thoughts on the shifting sands underneath independent filmmakers’ feet in the age of streaming and VOD.

Filmmaker: Let’s start with the origins of the project. You had just done Firestarter, which was your first major studio film. How did Commando come to you?

Lester: I was at the “Midsummer Night’s Dream” Playboy Mansion party, sitting in my pajamas next to Joel Silver. He said he had this script, and maybe I could direct it. I said, “Fabulous, can I read the script?” He said, “No, if you read the script you’re not gonna want to do the movie.” [laughs]

Filmmaker: Was Schwarzenegger already attached?

Lester: Yeah, they had Schwarzenegger, and when they told me the basic story I thought it sounded great. They just didn’t have a script that worked. So Joel brought in Steven DeSouza, who had worked with him on 48 Hrs., and he wrote a new treatment that we then developed the script from.

Filmmaker: The script you shot plays like a template for just about every Schwarzenegger movie that came out in the subsequent ten years. The exaggerated action, the one-liners…

Lester: Well, I saw it as a James Bond movie. I remembered seeing Dr. No when it came out when I was a kid, and I loved the one-liners in that. There were a couple of those in DeSouza’s script, and then we kept adding them throughout the movie as we went, partly because I got to know Arnold during the rehearsal period and learned how funny he was. We never stopped writing jokes for him and incorporating his own personality into the character.

Filmmaker: Did you have any other reference points aside from James Bond?

Lester: When I went in to interview for the job Larry Gordon, who was running the studio, kept saying he wanted it to be like this Jim Brown picture he had distributed when he was at AIP. I can’t remember the title.

Filmmaker: Slaughter?

Lester: Right, Slaughter. I had come out of the action and exploitation genres, so I said, “Yeah, I can do that.” It was sort of the natural evolution of my career. I was a student of action films and had been doing these kind of pop art genre movies. In Commando, we were always thinking about bright, almost comic book kind of colors. For example, in the scene where Arnold fights Bill Duke in the hotel room, the lamps are red and green, they’re never giving off just white light. We wanted that kind of vivid color throughout the picture, in both the production design and the cinematography.

Filmmaker: Did you find that it was easier to realize the effects you wanted to achieve when you moved into bigger-budget studio pictures like Firestarter and Commando?

Lester: That’s the funny thing, even to this day I almost never think about the budget when I’m making a movie. The job stays basically the same whether the budget is more or less. I don’t let it hinder my way of thinking. The one thing the bigger budget did afford me on Commando was a lot more stunts than I was used to, and a longer shooting schedule; Commando was around 45 days, which was short by today’s standards but a lot longer than what I usually had.

Filmmaker: Yeah, it actually sounds pretty short for a movie of this scale. How did you prepare?

Lester: I storyboarded the whole movie. I always do, but it was a necessity on Commando because I had to hand certain shots off to the second unit for the action sequences and stunts, and I don’t know how else we could have made everything match without that kind of planning. I’m always willing to modify the storyboards if I think of something better or a new opportunity presents itself on set, but I learned a long time ago that it’s best to have a plan going in so that you never stand around looking like an idiot who has no idea what to do. When that happens, the crew loses confidence in you pretty quickly.

Filmmaker: I love the whole cast in this movie – Arnold is obviously iconic, but then you surround him with great supporting players like Dan Hedaya and David Patrick Kelly. How long did it take you to assemble that cast?

Lester: Around a month. David Patrick Kelly came from 48 Hrs., which Joel Silver had produced, and Rae Dawn Chong…we saw dozens and dozens of your typical beautiful blonde actresses for weeks trying to find somebody who could play opposite Arnold. We read everyone you could imagine, and the scenes would just lie there flat. Then there were a lot of actresses who didn’t even want to act with him, because they thought they were too prestigious. I never heard of any of them again. [laughs] By the time Rae Dawn came in we just about hired her on the spot, because we finally had someone who brought real comedic flair to the part. We had to cut the love scene though – originally there was a sex scene between her and Arnold, but in those days the Southern theatres wouldn’t play a movie if it had interracial sex, so that was out.

Filmmaker: In addition to all the adults, you have a solid child’s performance from Alyssa Milano, who was pretty new at this point. How did you find her?

Lester: She was already on Who’s the Boss?, so she was brought in by the casting director and we hired her immediately. When you’re directing a child actor it’s a little different. I would just keep rolling the camera while I talked to her, feeding her different lines and reactions rather than shooting actual takes. I learned that working with Drew Barrymore on Firestarter.

Filmmaker: I wanted to ask about some of the locations, because you just destroy everything in this movie. How much was shot on sets, and how much did you shoot on location?

Lester: It was a mixture. The hotel, for example, was a façade we built on the beach, and then the interior was a set. There was a lot of location shooting all over LA. We used the Long Beach airport, we shot the mall stuff at the Sherman Oaks Galleria, we shot at the Harold Lloyd estate in Beverly Hills – Ron Burkle lives there now – and at William Randolph Hearst’s estate in San Simeon. That’s where we did the sequence at the end with the dictator. We were supposed to shoot in Palos Verdes, but at the last minute they told us we couldn’t because of environmental concerns or something – they were afraid of us blowing up stuff and it going into the water – so we went to the Hearst people and they let us do it on their private beach. We were all wandering around looking at Hearst’s artwork. A lot of it’s still boxed up in crates, like something out of the end of Citizen Kane.

The furnace room at the climax is actually on the lot at 20th Century Fox; in the script that fight between Arnold and Vernon Wells took place on a boat. The studio told me it was too expensive and too dangerous, and that I had to shoot the film on a location Fox already owned. I said, “Like where?” and the response was, “Well, just walk around the lot, figure something out.” So I wandered around and found a furnace room right next to my office that looked great and was free.

Filmmaker: Vernon Wells is such a great villain. Was it hard though, finding guys like him and Bill Duke who looked like they could convincingly hold their own against Arnold?

Lester: Yeah, I actually filmed a couple hours with another actor before we hired Vernon Wells. I shot one scene with this guy opposite Arnold and he was so weak that we all just thought, “Oh my God, this is never going to work.” We had to fire him and replace him with Vernon, who had been in The Road Warrior.

Filmmaker: Has that happened on other films, where you hired an actor and then realized you made a mistake and were stuck with them?

Lester: Oh sure. It happens, and you try to get rid of them, and sometimes their lawyers come in and it’s going to be expensive to get out of so you just live with the person. On one movie both of my leads were terrible! It’s difficult, because once you make that casting choice you’re hooked for the rest of the movie, especially once the camera starts rolling and you have film on them. I try as much as possible to vet my actors ahead of time, checking out their reputations – not just whether or not they’re good actors, but whether or not they’re going to make my life miserable.

Filmmaker: How much influence did Joel Silver have on the picture? This was right at the beginning of his rise to prominence as the biggest and most influential action producer of his era.

Lester: He was a genius. He really supported the idea of having a lot of comedy in the picture, because he had had that experience on 48 Hrs. – he kept saying, “You’ll make a lot more money if there’s comedy as well as action.” And he was right.

Filmmaker: On 48 Hrs. the powers that be at Paramount didn’t want Silver and Walter Hill to use Eddie Murphy – they kept trying to fire him, and then when the movie was a hit they signed him to a multi-picture deal!

Lester: Exactly.

Filmmaker: What was the studio response like to your film when you first delivered it? Did they know what they had?

Lester: The film was supposed to come out in January, and a few months before that I screened a cut for the studio – there were around a hundred people there, all the executives, publicity people, etc. After the screening the executives called Joel Silver and I into their office and said, “We have good news and bad news. The good news is, we love the movie; the bad news is, we’re releasing it in three weeks.” We had no sound, no music, and Joel Silver said, “No way, it’s impossible.” But Fox didn’t have any other movies coming out, and the way they looked at it they had thousands of employees just sitting on their asses doing nothing, so they were putting Commando out in the fall whether we liked it or not. Joel and I worked together with three editors and got all the post-production done, and it was released with no test screenings. The only preview was for the studio.

Filmmaker: Given how successful it was, I’m surprised you didn’t do more big studio movies. You did Armed and Dangerous and another studio movie or two, but basically ended up going back to your roots as an independent. Why did you leave the studio system?

Lester: When I made Showdown in Little Tokyo for Warner Brothers, my cut was 90 minutes and they released it as a 78-minute movie. I had no control over it, and I was very unhappy with the final result. Today I’d probably just brush it off and go on to the next movie, but back then I took it a lot more personally and decided I needed to be in a position of total control. I didn’t have the money to finance big studio-level movies myself, but I went to the Cannes Film Festival in 1993 with the intention of announcing a bunch of titles and finding foreign buyers to invest in them – this was also the time of the hot video market. I ran into people from Lionsgate, which was just starting, and they said, “We need movies!” I asked, “How many do you want?” and they said, “Ten.” They were looking to finance these movies for $3 million a piece, so over the next three years I directed ten movies back to back and had that control I was looking for – they got involved a little bit with the casting, but that was it. They gave me half the money and I raised the other half foreign. I was going to these markets selling foreign rights, and eventually I started acquiring other people’s movies too and wound up a distributor – I was probably the only director going around to all these markets, and I directed something like twenty movies that way. When you do that, though, the studios stop calling you – they figure, “Oh, that guy’s got his own company and he’s doing his own thing.” You don’t even occur to them any more, like you’re in a kind of bubble. I’m not sure if I recommend it, because you become less of an artist and more of a businessman, but I did enjoy doing all these movies in that $3 to $5 million budget range where I had complete control again, like I did in my early days as an independent.

Filmmaker: In the last few years the independent film business has changed so much with the decline of DVD and the rise of streaming and VOD and everything else. How has all of that affected you?

Lester: The changes have been completely radical to an insane degree. My son made an interesting point: he said that we’re now as many years away from my first film, which I made in the early ’70s, as that film was from the silent era. And the changes have been just as dramatic in that second forty-year period. When I made my first movies, there were only 125 or 135 films being made in America in any given year. Rolling Stone did full spreads on those early movies I did; I was covered in the Los Angeles Times for Truck Stop Women. Now you have 8000 movies being submitted to Sundance – there’s so much content. There are more venues in terms of streaming and VOD, but there isn’t enough income right now from those markets to sustain independent films unless people make them really inexpensively. The problem is that when you get down into this area where you’re making feature films for $50,000 it’s hard to achieve any kind of quality, and you’re competing with bigger-budgeted content. You’re competing for viewers against House of Cards. And it’s hard as an independent to sell material, because even when a new company gets into the game – like Amazon deciding they’re going to produce original content – who do they meet with? The studios. Anyone can make a film now, but the distribution avenues are still blocked by the major studios, who are all over these new methods of delivering content to audiences. And even they are having trouble monetizing it.

My personal opinion is that the feature film has collapsed, and that we’re going to go back to the origins of cinema. Movies started with shorts – Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton – and kids today don’t want to sit for 90 minutes to watch a movie. They might be willing to in the theaters, but when they’re at home on their computer or TV screen they want short content, and that’s why places like Funny or Die are doing well. To get people to want to sit still for a feature film and pay for it in the independent sector is a real challenge.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and iTunes. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.