Back to selection

Back to selection

Frederick Wiseman on His Banned Classic Titicut Follies

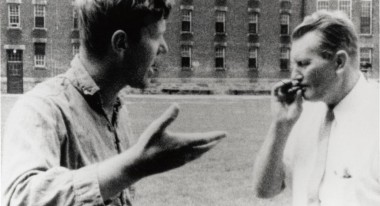

Frederick Wiseman courtesy of Nick Bruno

Frederick Wiseman courtesy of Nick Bruno Straight from its premiere at New York City’s Metrograph theater, the new 35mm print of Titicut Follies screened at Portland’s Northwest Film Center on April 21 with director Frederick Wiseman in attendance.

The controversial film portrays the wretched conditions at The Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane in Bridgewater, Massachusetts circa 1967. In unflinching cinema verite-style, Ttticut Follies presents a stark portrayal of the hospital’s predominantly naked inmates as they are mishandled, force-fed, taunted by guards, and locked in empty cells.

Titicut Follies was famously banned prior to its planned premiere at the 1967 New York Film Festival. Though Wiseman had gotten the requisite permissions, the state of Massachusetts claimed that the film violated the patients’ right to privacy and dignity. For years, the film was only able to be screened in academic settings. But in 1991, a superior court judge said the film could be released to the general public since most of the inmates had died and that First Amendment concerns trumped privacy concerns.

In the conversation following the film, Wiseman, now 85, said he hadn’t set out to depict abuses at the hospital, and that he doesn’t feel comfortable taking credit for any improvements in our mental health system in the years since Titicut Follies revealed such sordid conditions.

“It’s both naive, arrogant, and presumptuous for me or any other filmmaker to say that their film produces social change. In a democratic society people have access to information from so many different sources. You can’t isolate one thing and say that that particular poem or novel or film caused it,” said Wiseman. “I like to think the movie may have contributed to [Bridgewater closing], but I actually have no idea.”

Below are other highlights from the conversation:

On the title Titicut Follies

“Titicut Follies, as you see in the film, was organized around an inmate and staff variety show called Titicut Follies. In naming the film Titicut Follies, I picked up on the metaphor of the variety show,” said Wiseman, acknowledging that “for my other films, I’ve always had rather laconic titles.”

How he managed to film such gut-wrenching situations

When asked how he was able to witness such horrible treatment at Bridgewater Hospital and not intervene, Wiseman said it wasn’t a problem for him.

“When you’re making one of these movies, you’re working. The fact that you’re working is a real defense against all of the things you’re seeing and hearing,” he explained. “Your job is to get the sequence. Your job is not to identify or at least not overly identify with what you’re seeing and hearing. Because I’m very busy and the people working with me are very busy, you tend to think about it afterward.”

On getting permission to film

“Curiously enough, for most films, it’s been extremely easy to get permission. My big secret is that I ask,” said Wiseman. “I’m always amazed that people say ‘yes.'”

But there have been a few occasions where he didn’t get the access he wanted. He was initially planning to shoot the film, which eventually became Law and Order, in Los Angeles. “I was told I could do whatever I wanted except ride around in police cars,” he recalled. But since there were no foot patrols at the time, his access was limited. Instead, he opted to go to Kansas City where “I could freely do whatever I wanted,” he said.

On full disclosure

To get permission to film inside Bridgewater Hospital, Wiseman said he “told them from the beginning the kind of movie I was doing.” He said he made it clear that the film would be shown widely and that he’d get final cut. “I always make a full disclosure of the method and the procedure,” he explained. “It’s extremely important to make a full disclosure about what you’re doing – not only is it the ethical thing but it also means nobody can come back at you if they didn’t like the movie.”

Of course, the full disclosure didn’t prevent the state of Massachusetts from banning the film due to alleged privacy issues. But Wiseman is proud of the fact that no inmate or member of an inmate’s family ever complained about the film. “It was banned as a result of political decisions,” he explained.

How he finds a film through the editing process

Wiseman said that not only was Titicut Follies his first film as director, but it was his first film as editor. “As a result of editing a lot of other films, if I were editing this (Titicut Follies) now, I probably wouldn’t have done many of the things that I did,” he explained. As an example, he said he would not have intercut a scene of an inmate being force-fed with scenes of his funeral. “Now that I look at it, I find it too heavy-handed. When you intercut the force-feeding with his funeral, I’m telling you what to think, that he’s treated better in death than in life.” Wiseman said it’s always best to let the audience draw their own conclusions. “At the time, I thought it was a great cut,” he said.

It’s through the editing process that Wiseman finds his stories. “The film emerges through the editing,” he said.

For Titicut Follies, he had about 80 hours of footage, whereas for his latest film, In Jackson Heights, he shot 140 hours. By comparison, for At Berkeley, he captured 250 hours “because academics like to talk,” he joked.

Wiseman’s filmmaking procedure has been, he said, “pretty much the same in all the films. I have no idea in advance what the structure or point of view of the film is going to be.”

He doesn’t like to do advance research, he said, because “the shooting of the film is the research.” Also, he doesn’t want to miss out on getting good material on camera. “I don’t like to be present at a place when something interesting is going on and not be able to get it for the film,” he said. “Since nothing is staged, I’d be very unhappy if I was there doing research and something really great happened. I’d rather take the risk of overshooting a bit.”

The real model for this kind of filmmaking, according to Wiseman, is Las Vegas. “It’s the roulette wheel. You take the risk of shooting a lot of film with the hope that you get enough material out of which you can cut a film,” he said. “I have no idea what the structure is going to be, but I’m willing to take the risk of shooting a lot and finding the film in the editing.”

Wiseman takes his time with the editing process so he can “think about the consequences of starting the film one way and ending another way.”

After reviewing the rushes, he’ll put aside maybe 40 percent of the material and edit the sequences he thinks he might use in the film without any idea of the order he’ll use them in. That process alone might take him 6-7 months. “It’s only when I edit the so-called candidate sequences that I begin to work on structure,” said Wiseman. “One of the most interesting things about making movies of this sort is that at least 50 percent of the editing has nothing to do with the technique of editing. It has to do with studying the rushes.”

He explained that “unless I feel I understand what is going on in individual sequences, I can’t decide if I’m going to use the sequence and where I’m going to place it. I have to delude myself into thinking I understand everything that’s going on in a sequence in order to make a decision whether or not I’m going to use it.”

The other consideration when editing a sequence is to be sure that it “doesn’t violate what went on in the original sequence, which is often much longer than what I use.”

He does not edit for length, saying that “the length of film is whatever the film comes out to be in the editing room. I don’t set out to make a film that’s 82 minutes,” he said.

On why he shifted to digital

“I changed to digital reluctantly merely because Kodak stopped making the negative and the labs went out of business,” he said. “Those are two powerful incentives to change. In terms of the shooting of the film, it’s possible a little more is shot because you don’t have the processing costs.”

That said, while the general consensus is that shooting digital is cheaper than film, Wiseman said, “it’s not that much cheaper because finishing costs are more expensive and color grading is more expensive,” though, of course, you save on film processing costs.

How he selects topics

“I really make movies about subjects that I want to make movies about,” Wiseman told the audience. “I don’t believe I’m obliged to make movies that always deal with the lives of poor people and whatever relationship they have to the state.”

Ultimately, he said, “I’m trying to make movies about as many subjects as I can.” He’s made dance films such as Ballet and La danse and Crazy Horse simply because “I like dance.” In fact, Titicut Follies is in the process of being made into a ballet choreographed by James Sewell of Sewell Ballet (which Wiseman discussed in a previous article in Filmmaker). A sneak peek of the ballet was presented at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, along with a screening of Ttticut Follies. The finished ballet will premiere at the Skirball Center at NYU in Spring 2017.

“I am a ballet fan and I got tired of seeing ballets about relationships, whatever that may mean, so I thought it would be interesting and challenging to see if we could make a ballet on a more contemporary subject,” Wiseman explained.

Finally, when asked a question about advice he’d give to young documentary filmmakers, Wiseman had two words to share: “Marry rich.”