PLAYER HATERS

A bitter and bracing look at Hollywood lost souls, Catherine Jelski’s The Young Unknowns has polarized audiences on the festival circuit. Matthew Ross talks with Jelski about her three-year struggle to complete and release her debut feature.

|

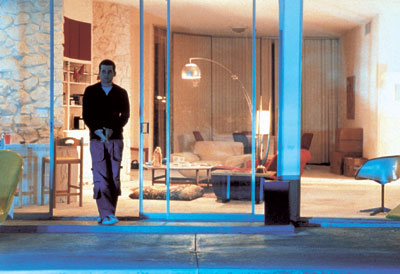

| Eion Bailey in Catherine Jelski's The Young Unknowns. |

It’s been a weird, surprising journey for writer-director Catherine Jelski and her debut feature, The Young Unknowns. A dark drama about the Hollywood Hills’ Less than Zero set, the film chronicles one day in the life of Charlie (Devon Gummersall), the spoiled but emotionally neglected 20-something son of an A-list British television commercial director, and Paloma (Arly Jover), Charlie’s put-upon production coordinator girlfriend. The film was completed in March 2000 and premiered the following year at SXSW, where reactions ranged from ecstatic to accusatory as many audience members had trouble accepting Jelski’s unsentimental portrait of an emotionally abusive relationship. Yet her assured direction and the intense performances of the young cast (which also includes Eion Bailey and Leslie Bibb) impressed Toronto Film Festival director Piers Handling, who selected the film for his 2001 program. The high-profile Toronto berth resulted in several other festival invitations, and the film eventually wound up in the hands of micro-distributor Indican Pictures (Hybrid, Down and Out with the Dolls), which will give The Young Unknowns a limited theatrical release in April – more than three years after it was finished.

The 50-year-old Jelski worked as a nightclub dancer in Europe before coming home to the U.S. to study theater directing. She then cut her teeth on film sets as a script supervisor for the likes of Wim Wenders, Richard Linklater and Charles Burnett before embarking on The Young Unknowns, which is loosely based on Wolfgang Bauer's play Magic Afternoon. Filmmaker’s Matthew Ross spoke with the director about overcoming naïveté, dealing with the industry and why she thinks her film has elicited such extreme reactions from audiences on the festival circuit.

Filmmaker: This film has taken a rather unusual journey in terms of its festival run and its eventual acquisition. What have the past three years been like for you?

Catherine Jelski: Well, this is my absolute first film. I was a complete virgin at this whole festival game, so of course there were a lot of things that I didn’t understand, like, whom you have to get in your corner before you even start applying. I was really pretty naïve about it, and I stumbled out of the gate. I sent in a copy to Sundance – I was one of those foolish people who walked in their unfinished film off the Avid on the last day. I could have just thrown it in the garbage as easily.

|

| Catherine Jelski. |

I was determined that I was going to get distribution for the movie. But I was not expecting to get a national theatrical [release] – that really surprised me. And since I’d been doing a lot of learning and reading on the festival circuit, I initially was very skeptical of Indican Pictures wanting to go theatrical. I thought they should just sell video and cable, and we should try and recoup as much as we could. But they were adamant that they felt that the film could play. And as the bookings have started coming back in, I’m starting to feel that way too.

Filmmaker: What were your expectations going in?

Jelski: Well, my expectations were of course that the actors and I were going to do beautiful work and we were going to be duly rewarded by a small audience. I guess I was just blissfully ignorant of the realities of the festival world and the independent marketplace.

Filmmaker: Yet at the same time you raised enough money to shoot on film and to cast some young, experienced television actors. How did you line up the resources to get this into production?

Jelski: Well, the financing was just one stumbling block after the next. Basically, it was money from family and friends. I joked that I couldn’t raise a nickel from anyone that I either wasn’t related to or hadn’t slept with. I inherited some money from my mother, who had passed away a few years ago, and I spent all of that. And then I wound up putting postproduction on my credit cards. I would have to stop to earn the money to cut the negative and do my opticals. It just went on and on, but we pieced it together.

From soup to nuts, it cost us $200,000, and we hired the actors on a limited exhibition contract, so we paid them $75 a day, and I still owe them. SAG is being fairly nice to me so far with the theatrical [release]. Once I get to video and cable, they’re not going to be so nice – I’m going to owe [the actors] deferrals. But I’m trained and experienced as a theater director, so I’m very, very picky about my actors. I knew straight away that I needed casting directors to help me get to people who could play these roles. And I was fortunate to be guided to Dan Shaner and Michael Testa, who specialize in young Hollywood, and they earn a living doing television.

Filmmaker: Obviously the story of the film is about people who either work in television commercials or are trying to get in the door. Was the script based on your experiences as a script supervisor in that world?

Jelski: It really was in certain aspects. I worked for this British commercial director who was quite successful. I think he was on his fourth wife and fourth family. And every once in a while on the set, his oldest son would show up, this strange half-British, half-Hollywood boy, and I just kept thinking: What must it be like to be this guy’s firstborn child? [The film] kind of grew out of that question. The whole commercials world is so odd, but it seemed such an analogy to sort of the consumerist mess we’re in. It seemed to speak so much to our times.

Filmmaker: In the past you’ve mentioned that you’ve been in your share of emotionally abusive relationships, and that this film is in part based on those experiences.

Jelski: Well, I’ve always said that any woman who hasn’t been in some kind of emotionally abusive relationship has either been very lucky or else she’s lying. I think for young people in our society living within this late stage of capitalism, there’s just so much estrangement and hostility. I think it’s hard for young people to learn how to love someone.

Filmmaker: You push the boundaries in this film in terms of not making the character sympathetic or likeable. Was that a concern for you going in? Or was it purely intentional?

|

| Devon Gummersall and Arly Jover in The Young Unknowns. |

Filmmaker: Extraordinary in what way?

Jelski: I mean, people have been furious. At SXSW, after the very first screening of the film, the Q&A was just packed. Nobody left. Afterwards, I was in the lobby, and this producer comes in and says: "Hey, I didn’t see your movie, but I have to compliment you on your lobby. They’re all out there fighting with each other." People were really arguing, and both the supporters of the film and the people who were appalled would not leave.

Filmmaker: I assume they were appalled at the fact that Arly Jover’s character is so masochistic. Is that it?

Jelski: Yeah, that’s the way they view it. I mean, we’ve all [behaved like her]. Not in such an exotic or elaborate way, perhaps. I don’t believe we live in a society of victims, but I believe women are as flawed as men are. I think we’re hurting each other, and it’s very complicated. People don’t like to get close to that – they don’t like to feel that things are complicated.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →