FESTIVAL ROUNDUP

- Cannes Film Festival by Noah Cowan

Gen Art Film Festival by Noah Cowan

docfest by Eugene Hernandez

New York Underground Film Festival by Michelle Handelman

Los Angeles Independent Film Festival by Stephen Garrett

San Francisco International Film Festival by Jennie Yabroff

Santa Barbara International Film Festival by Stephen Garrett

Cannes Film Festival

While many important films premiered in front of attractively dressed people at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the big story on the beach was the regal blessing accorded the American indie scene. Four films appeared in Competition plus a handful in the Director’s Fortnight, all produced in the United States outside of studio-based development and production systems. Further risking immodesty – after all, Filmmaker is a cheerleader for just this kind of work – the Festival was even more specifically laudatory: it celebrated the filmmakers who emerged from New York in the early ’90s and their powerful aesthetic influence on the film world

I primarily mean two people here, Hal Hartley and Todd Haynes, who appeared in Competition with Henry Fool and Velvet Goldmine respectively. But I also mean Clean, Shaven’s Lodge Kerrigan and the actor-turned-director John Turturro, in Competition with their new films, Clare Dolan and Illuminata; as well as Welcome To The Dollhouse’s Todd Solondz, with his newest Happiness; novelist Paul Auster’s first film as sole director, Lulu On The Bridge; Tamara Jenkins’s Slums Of Beverly Hills and Sundance winners Mark Levin (Slam) and Lisa Cholodenko (High Art). This is a particularly fine cross-section of filmmaking talent from New York and represents in many ways the breadth of accomplishment that has happened in that city over the last decade. For the Queen of Festivals to take on a bargeload of films from the same gene pool is, especially in France, very much a political act – especially for those of us who remember waiting for the annual lone American independent selection to be announced. Obviously there are huge disparities in accomplishment between these films. Nevertheless, the best of them represent the most thoughtful and radical positions available in narrative filmmaking today. Festival director Gilles Jacob and Fortnight director Pierre-Henri Deleau seem eminently justified in choosing this year for their coronation ceremony a l’Americain. And this consensus is more surprising than it might at first look.

"Cannes" is actually three or four different festivals, administratively separate and jealous of each other’s position, which take place in the same legendary town. While one would be hard pressed to call the place "magical" or "breathtaking" (per the Huck Finns of American journalism), it does have a certain faded allure in its glamorous (if aging) beach side palace hotels – the Carlton, the Martinez, the Majestic – and the Monegasque yachts moored off the azure Cap d’Antibes. The stone monstrosity that houses the Festival itself, the Palais des Festivals, looks more like a Vegas convention centre a la ’70s Elvis than the film mecca it represents. Even so, its facilities are irreproachable: films just look better on those big screens. Of course only the films of the Competition and Un Certain Regard (the farm team) play there. The Director’s Fortnight is in a fairly grim basement, albeit with terrific projection, in the Noga Hilton hotel; the Critic’s Week plays out in two unspeakable town cinemas and the films of the Market play in cinemas used so occasionally that fantasies of Legionnaire’s Disease regularly play across one’s mind.

|

| Justin Elvin and Dylan Baker in Todd Solondz' Happiness, a hit at Cannes. |

The Competition was, according to the New York Times and a few others, relatively disappointing this year. This is fair; few films made for a good brawl and that’s the great joy of festivals. The only official outrage really came from the Danes, with their two films in Competition produced under the "Dogma 95," a manifesto (more or less) demanding the application of the principles of Lars von Trier’s Breaking The Waves to the films by the undersigned. That means lots of hand-held camera, naturalistic performance, on-sight sound, few opticals, little cross-cutting and, I suppose, a desire to expose the hypocrisy of Danish (or European?) society. The film that people liked, Celebration by Thomas Vinterberg, sees a large rich family gathered at a country hotel to celebrate the patriarch’s birthday. Hatreds are on the surface and none of the relatives – even the hero, a self-contained blond cutie-pie – are particularly nice. Things are kept in check until the cutie includes in his toast a reference to his and his sister’s molestation at their father’s hands. This dramatic moment is then impressively sustained for another 20 minutes of knife-twisting pain until the proceedings recede to the ordinary staples of the "evil parent" movie. The film’s relatively conventional narrative arcs and movie-of-the-week themes provided enough comfort for most critics so that the film’s often impressive cruelty and austerity became more digestible.

Not so with Lars von Trier’s newest, Idiots, loathed by critics and public alike. This is an art film as confrontational and mean-spirited as anything Fassbinder ever made, in an era not accustomed to such aggression. A dazed-looking middle-aged woman gets caught up with a bunch of rich kids living communally in a beautiful suburban house owned by the group leader’s uncle. For no reason they feel the need to explain, their sole passion in life is to go into public settings – a community swimming pool, a roadside restaurant, a factory "open house" – and "act like spazzes". They imitate people suffering from mental illness in order to wreak havoc, eliciting only pity and stern looks. While the inevitable happens – the leader tries unsuccessfully to get everybody to integrate "spazzing" into their work life; the house gets taken away from them; the group breaks up – the build-up to its denouement is a fascinating exercise in audience humiliation. Do you laugh? The situational humour is flabergastingly funny, especially within the documentary realism of the "Dogma," but virtually every scene contains a moment of very "bad taste." Just when you think you have it solved – Ahh! They are showing their contempt for society by showing how easily disrupted it can be! – von Trier raises the ante of offensiveness one more notch, challenging you to call him a dumb Neanderthal. I found it brilliant. The film also has one of the great final payoff scenes ever filmed; and even this does not resolve the central enigma of the work.

The only other film that prompted this much reflection in Competition was Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine, even if it is Idiots’s emotional opposite. A heartfelt gay love poem to rock’n’roll, Haynes portrays glam rock through a series of characters whose worlds are (almost) purely historical. Told mostly through voice-over flashback, press "happenings," public (or publicly-staged) events and tons of performance, the film provides maybe three conventional narrative scenes – you know, where people reveal things about themselves through dialogue – to hang the story from. Because of this, Haynes was accused of making a "cold" film; nothing could be farther from the truth. The giddy expectations of fame, the transience of love, the ego-driven glory of being loved; it’s all there. And told with a stunning camera and jaw-droppingly sexy songs.

The balance was made up of the charming (Erik Zonca’s enticing Paris saga The Dream Life Of Angels; Nanni Moretti’s conflation of his son’s birth and the rise of the Italian Left, Aprile); the sternly formal (Theo Angelopoulos’ Eternity And A Day; Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai) and the failed crowd-pleasers (Turturro’s Pirandello-esque Illuminata and, although the rest of the planet seems to be charmed, Roberto Benigni’s ridiculous Nazi comedy Life Is Beautiful). Hartley’s film has been addressed in this magazine already, but it is worth saying again that it represents a major advance for his "Dogma" and a welcome broadening of his artistic scope. Out-Of-Competition is reserved for Hollywood garbage and films by very old men. In the latter category was Carlos Saura’s newest dance opus Tango, Manoel de Oliveira’s newest meditation on whatever all the others are meditations on, Inquietude, and a small delight from Shohei Imamura. His Kanzo Sensei tells the story of a country doctor celebrated for identifying chronic hepatitis in wartime Japanese civilians; but he humorously subverts the cliches of the historical biopic by adding incongruous sex talk, morphine junkies and the other exquisite twists we have come to expect from this ever-surprising septugenarian.

"Un Certain Regard," the parallel section programmed (basically) by the Competition folks, always suffers by comparison with the Competition on one hand; and with the Director’s Fortnight, with which it shares the same "vision" – new or challenging work, (somehow) inappropriate for the Big Room – on the other. Last year, a particularly strong collection of films in this section (of about 30 features) was thought to signal a new seriousness in the section’s programming; less a football for political selections and more a truly "informational" section about the goings-on in world cinema. A few baffling choices – all American, interestingly enough – put this new thinking into question, but the general tone was still very positive and several important new films premiered here.

Clearing the American turkeys out of the way first: the opening film of the program, Paul Auster’s Lulu On The Bridge, was a disaster – an overly-determined love story, premised on a flaky New Age concept, with a retro-silly jazz vibe and somnolent acting — it was a monumental disappointment in the wake of the light-hearted and charming Blue In The Face, for which Auster received a co-directing credit. Jake Kasdan’s Zero Effect, an unnotable winter release in America, was given star status in the program, rather clouding Kasdan fils’ denials of nepotism. Stanley Tucci’s new film The Imposters adores the uproar and showmanship of the Silent Era and designs a story of two actors who become stowaways around the period’s most famous stylistic moments; yet its effect was less than inspirational. A complicated failure – is period slapstick too erudite? How do you make accessible films about performers (after Ishtar)? And those costumes, post-Sting? Finally, I suppose, Tucci chose not to believe that much of silent cinema’s charm came from people not talking.

As for the triumphs, consider these radically different three. Divine is a zeugma of the Old Testament and Seven Stations of the Cross according to Mexican cinema god Arturo Ripstein (Deep Crimson). Enigmatically mixing chapters, restaging it all in a low-rent Christian cult in the scrub and featuring a nymphomaniac Virgin Mary/Moses obsessed with a sub-Mario video game, the film is arrestingly intelligent and deliciously fun. The Killer is the latest in Darejan Omirbaev’s films (also Kairat and Cardiogram) about the Kazakhs in post-Soviet Russia; for my money, his descriptions of the inevitability of a life of crime and the nihilistic collapse of any societal values in post-Soviet Russia outgun the much-celebrated, similarly-themed and recently released The Friend Of The Deceased. John Maybury’s film about Francis Bacon, Love Is The Devil, was described recently by a (decidedly unhomophobic) friend as "too ‘gay,’ overdetermined, reductive and overly stylized." These criticisms have a certain justice: the film is unflinching in matching Bacon’s unconventional use of light and figure with the film’s cinematic look; the connection between the sense of inevitable decomposition in Bacon’s paintings and the eerie way the painter’s relationship collapses with his East End stud boyfriend also signals both a singularly gay nihilistic approach to human relationships and draws on an obvious "tortured artist" genre. Were this simply just another po-mo graveyard run at a gay anti-hero, little more would need to be said. And it is true that Love Is The Devil may have at its center a tragic, mean-spirited fag and a loutish exploitative drama queen of a boyfriend. For many of us, that makes the film’s ability to convey a core of (tortured, spiteful, repellent, utterly moving) romantic love so extraordinary. Maybury’s genius is to rest a fragile melodrama on an ultimately awesome if dense edifice of theory, history and cinematic representation of artistic accomplishment. I also defy any critic to show me a narrative film with this many images that appear entirely new.

Reeling from a tragic 1997, the Director’s Fortnight returned with a triumphant 1998. A consistently strong, focused and intelligent selection challenged the Competition daily with its "finds." The consensus triumph of the section was Todd Solondz’s formidably intelligent and extremely funny Happiness. While every hack this side of the Pacific will write about the film’s "troubling pedophilia," the real story is his audacious appropriation of Robert Altman’s narrative style and ability to make it relevant again. After Nashville, Altman used the shaggy-dog style to avoid the full exploration of the often troubling questions he posed on the surface of American society. Solondz looks like he is doing the same until we are suddenly upbraided by the consequences of the action of his characters and our laughter. So, while the Jersey father’s admission to his son that he’s drugged and screwed the kid’s best friend is quite a scene, a flaky girl’s realization that her dreamy affair with a Russian taxi driver caused his wife to be beaten to a pulp somehow becomes far more horrifying because it is so genre unfriendly. This brave film is a monument to the brutal efficiency of sardonic wit.

Also in the Fortnight was Yvan Le Moine’s charming, very sexy Fellini tribute, Le Nain Rouge, about a dwarf who writes love poetry to a rich zaftig starlet (played, of course, by Anita Ekberg); Don McKellar’s perfectly scripted, stunningly shot (in radical brown and gray contrasting shadows) and poignant meditation on the world’s end, Last Night, was a triumph for Canadian cinema; Ziad Doueiri’s West Beirut intricately immerses two teenage boys just looking to get laid on the newly-drawn Green Line in early civil war Beirut; Mimmo Carlopresti’s La Parola Amore Esiste encapsulates a very contemporary fear of some Europeans that the capacity for love may have been eclipsed by a need for spurious personal insight, driven by both therapy and our individualistic society. Also notable was the great success accorded Sundance triumphs High Art and Slam in this section; the French went crazy!

The Critic’s Week felt smaller this year; smaller even than its official role as the smallest official Cannes section. This was mostly because it was tossed out of the Palais des Festivals, and forced into commercial cinemas too small to accommodate it. A couple of the films it presented were very good. Gaspar Noé’s Tous Contre Moi is a frighteningly powerful bile-spewing from inside the mind of a (in Noé’s mind) "typical" Frenchman: racist, sexually obsessive (especially about his daughter), murderous, mean-spirited, cheap, etc. An obviously caustic portrait of current France, it is always cinematically intense and enriching in a sort of filthy way. Francois Ozon’s Sitcom is the lighter side of Noé’s vision. All the evil and sexual perversity of Tous contre Moi is here but wrapped in, well, a sitcom. A mouse enters a well-adjusted household and transforms everyone into their true inner self. The nerdy son turns into a promiscuous fashion queen, the daughter becomes a sadistic suicidal horror, the mother a Mother Teresa sexually obsessed with her gay son and the father seemingly stays the same. A total hoot until it loses itself in the last ten minutes, Sitcom will surely enjoy a happy run at gay festivals and perhaps in a few theaters.

The Market usually yields some gems. Not this year. The great hot "find" was meant to be Waking Ned, an irritatingly twee tale of two Irish country geezers who stumble onto the winning ticket of the big lotto in a dead man’s hand. Perhaps retitled The Full Blarney, because it is surely born from the same school as that middlebrow rubbish, it will find its pot o’ gold underneath the Angelika rainbow promised by its selling price – a figure far in excess of any film I described above.

Gen Art Film Festival

Gen Art gets a lot of flack for being a "party" festival. Each film shown at the New York City-based event is explicitly marketed with a party attached, usually in some fashionable SoHo night spot. Those who believe in the sanctity of the cinema deplore this cross-breeding of evening activities. Many film professionals who attend the parties claim they don’t know anyone there, and that this somehow makes the Festival lightweight.

|

| Photek in Iara Lee's Modulations |

This is all bosh. Festivals have been founded on far more suspicious foundations than this, and in fact one big one – that I happen to work for called the Toronto International Film Festival – was born with more or less the same idea. By attaching a nightly glamorous event to a series of films, you create a unified event, especially in New York, where the term "festival" is close to the realm of cliche.

So the concept is a good one and was certainly beneficial to the stronger films in the Festival. Modulations, Iara Lee’s marvelously entertaining and surprisingly in-depth look at the cutting edge of the music scene, is tailor-made for Gen Art; a kick-out dance party after the film has given the film’s distributors a solid word-of-mouth foundation to build on its Sundance debut. S. R. Bindler’s documentary Hands on a Hard Body also will benefit from the exposure when it opens later this summer. This cinematic oddity chronicles a contest in Texas which awards a new truck to the person who can keep one hand touching it for longest. With much to say about the "American Dream" and all that, although without much cinematic muscle, it has now been positioned as the kind of documentary should get significant cable play after its theatrical debut.

The opening film, Adam Bernstein’s Six Ways to Sunday, is an updated film noir with off-kilter dialogue spins and some stylish shots. It also feels depressingly dated, more like a tribute to early ‘90s independent film than a new film of energy and substance. It was an unfortunate opener.

The balance of the Festival was bleak. Marcus Speigel’s The Farmhouse came across as a silly Southern gothic yarn, even with the radiant Blythe Danner at its center. Rocky mountain stoner saga Scrapple is a fun idea – to do with a pig and a shipment of pot – that never takes off.

Gen Art finally faces the same problems as every other festival – the dearth of good films to hang premiere events on – but it is at least going into battle armed with a smart concept.

docfest

Founded by non-fiction filmmaker Gary Pollard, in part, as an answer to New York’s defunct Global Village Documentary Festival which ran for over 15 years at Manhattan’s Public Theater, "docfest" — the New York international Documentary Festival — debuted as the first project of The New York Documentary Center. The Center is a new non-profit New York entity aimed at developing an audience for, as Pollard stated, "documentaries of vision and impact which do not necessarily fit the mold of commercial distribution."

Sixteen films, mostly premieres with a sprinkling of classics, were showcased during the five-day event comprising a lineup pulled together by program director David Leitner . By all accounts the event was a hit — the festival drew large crowds throughout its run at the recently re-furbished Director’s Guild Theater on 57th St. Among the moviegoers were many of the doc community’s familiar faces, including D.A. Pennebaker, St. Claire Bourne, Barbara Hammer, and Macky Alston. Rounding out the scene, Madonna and Rosie Perez even showed up to catch a Saturday night screening.

|

| Timothy Speed Levitch in Bennett Miller's The Cruise |

Bennett Miller’s The Cruise and Vicky Funari’s Paulina stood out as two of the all-around strongest entries. Miller’s The Cruise, a black & white portrait of NYC tour guide Timothy "Speed" Levitch that was shot entirely with a consumer mini-DV (digital video) camera and presented on 35mm, packed its Saturday afternoon screening and electrified attendees. Guided by the steady hand and eye of one-man crew Miller, The Cruise resonates from its opening moments as nasal-toned Levitch narrates a tour downtown. What begins as a hilarious look at one New Yorker and his city, becomes a moving portrait of a sorely misunderstood creative soul. Joining Miller for a post-screening Q & A, Levitch, tears streaming down his face, took the stage to meet the adoring crowd. The session was a fitting coda to the film — extending the unique portrait and offering a brief slice of what, for Miller, resulted in over 100 hours of footage. At press time, Bennett Miller and rep Jed Alpert were navigating continued distributor interest in the project.

Also emotional was the Q & A session for Vicki Funari’s moving biography Paulina about Paulina Cruz Suarez, the title character in the filmmaker’s portrait of a women who helped raise her while Funari’s father was stationed in Mexico City. Weaving together interviews of Paulina and family with dramatic re-enactments to illustrate key moments the woman’s life, Funari crafts a powerful documentation of Cruz Suarez’ harrowing life. Paulina’s perseverance and ability to overcome a childhood marred by rape and social rejection is a testament to the woman’s internal strength. So, as the diminutive, soft-spoken woman sat on-stage preaching her message of survival after the screening, many in the crowd were moved to tears. The film will be released later this year by San Francisco based Turbulent Arts.

Another Q & A filled with emotion, but of a different sort, was the discussion after Maggie Hadleigh West’s aggressive documentary, War Zone. West, video camera in hand, walks big-city streets awaiting a straying glance or catcall from a male observer, at which point she springs into action, interviewing the men to determine their motives and tell them face-to-face and on camera how demeaning and offensive their actions are. A fraction of her confrontations are included in the film, but her agenda to counteract "street-abuse", as she call it, is clearly portrayed. During the Q & A, West was generally praised, mostly by women, for her stirring film, but when one woman in the balcony questioned her method and another bristled at her decision to include Penthouse Magazine as a film sponsor, the filmmaker sharply disputed their points — defending her approach and pornography. Exhibiting some of the same interpersonal tactics that she used when questioning men in her film, West left the two women ruffled and frustrated long after the post-screening session had ended.

Earlier in the week, David Douglas’ Oscar-nominated The Fires of Kuwait kicked off the festival during a special IMAX screening, while the following night, docfest looked back at two classic television documentaries that poignantly illustrated the Vietnam War experience for a mainstream Network audience. Both broadcast on CBS in 1967, Morley Safer’s Vietnam: A Personal Report and The Anderson Report. On hand to discuss his program, Safer sounded like a seasoned indie filmmaker as he detailed battles with the network to guarantee his vision remain intact when the show was broadcast.

In a move that probably would have made Safer’s "60 Minutes" proud, filmmaker Ulrike Koch snuck a miniDV camcorder into Tibet to create the festival’s other documentary shot entirely on digital video. Koch’s The Saltmen of Tibet stood out with its deliberate, thoughtful pacing and spectacular shots of the Tibetan landscape. As remarkable are the intimate moments, afforded only by such a small camera, as we witness everyday exchanges — the nomadic Saltmen cooking or simply talking inside a confined tent. By documenting what Koch would later admit was a waning annual ritual, she gives viewers what probably would have previously been an un-documentable journey. Zeitgeist is releasing the film, with a fantastic looking 35mm print, starting with a run at New York’s Film Forum this summer.

Analog and digital video played a major role in the production of docfest films — all but one of the new works (produced in 1997 or 1998) were shot at least in part on video. Four were shot at least in part with a digital camera. To explore the new wave of digital technology David Leitner moderated a popular Saturday morning seminar entitled, "Documentary Making in the Digital World". While the panel was mostly filled with companies hawking their wares, attendees were given the opportunity to get a better grasp on emerging technologies, including the coming of high-definition television, the flexibility afforded by a telecine artist, the options for digital video cameras, and the potential distribution opportunities available in the new DVD format.

A filmmaker who certainly understands the excitement of doc-making in a time when technology is creating new opportunities and flexibility, is noted French documentarian Jean Rouch. Now in his 80’s, Rouch, the father of "cinema verite," used the new Eclair camera in 1960 to create his landmark film, Chronicle of a Summer. He presented the film on Friday night, attended festival screenings, and participated in a Sunday discussion with filmmakers Albert Maysles (Salesman, Grey Gardens) and D.A. Pennebaker (Don’t Look Back, The War Room). His presence throughout the festival unified the event just as his groundbreaking verite film provided a unique context for viewing the docfest films.

With docfest, Festival Director and Founder Gary Pollard and staff have not only launched a much needed new festival for non-fiction work, but with the Documentary Center, they have the potential to solidly promote a continuing movement. Among the goals that Pollard has unveiled for the future are a docfest film tour, year-round doc screenings in New York City, and an annual filmmakers retreat conference on Block Island, Rhode Island.

New York Underground Film Festival

Now in its fifth year, The New York Underground Film Festival has proven that stability can engender revolution and that subversion will always be best propagated by those with little stake in the mainstream.

Started in 1994 by Todd Phillips and Andrew Gurland (producers of Screwed and co-directors of the Sundance hit Frathouse),The New York Underground Film Festival spilled some bad blood around in its early days, with filmmakers complaining of insolent treatment, over-sold screenings, and a sense that the festival was being used as a career-launching pad for its directors. Now transfused with the passionate and festival-savvy blood of director Ed Halter, the New York Underground has renewed itself as a friendly stomping ground for both the criminally-minded and perversely-enabled. Halter, a former volunteer and programmer of The New York Underground and The San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Film Festivals, attracted more films, viewers and media attention this year while never forgetting that it’s the filmmakers who make a festival. Thusly, he indulged them with free lunches, drinks, nightly parties.

|

| Paul Duhoffman and Bonnie Dickenson in Todd Verow's Shucking The Curve |

"Underground film is about the underground filmmaker," remarks Halter. "Transgressive content may be a factor, but as it gets harder to shock an audience, The New York Underground becomes more about where filmmakers position themselves in society." Halter cites Jeff Krulik (Heavy Metal Parking Lot) and James Schneider (Oasis, Blue is Beautiful), two DIY filmmakers from Washington D.C. who traveled around the country showing their films in basements and bars without any concern for industry recognition. Halter adds, "We also have filmmakers like Todd Verow, who went from experimental films, to indie features (Frisk) and now he’s directing and producing a series of films with his own Warholian-type ensemble. These are filmmakers who blur the lines, who by hook or crook, find ways to put their vision up on the screen." True to his vision, Halter implemented the Film Core Fund last year, comprised of membership fees and festival revenues, and it’s the only place celluloid sociopaths can go to acquire finishing funds for their latest in-yer-face opus.

The guest of honor this year was Doris Wishman, the grand dame of ’60s exploitation films, who confounded the audience after the screening of Bad Girls Go to Hell by claiming, "I don’t know why they call it sexploitation – there’s no sex in my films!" Wishman, the queen of contradiction, has made over 25 films featuring lascivious men and lesbian seductresses, fishnet-covered flesh and more than a few rape fantasies. Featured were her classics: Nude on the Moon, a silly sci-fi fantasy about two scientists who arrive on the moon only to find it populated by buxom moon goddesses wearing gold-lame bikinis and tinfoil antennae; Double Agent 73, starring the overly-endowed stripper Chesty Morgan as a private detective with a hidden camera surgically implanted in her gargantuan 73-inch breasts; and Let Me Die A Woman, probably Wishman’s most sincere film, about the life of transexuals in New York City during the mid-’70s. Whether you love ‘em or hate ‘em, – and Wishman insists you better love ‘em – her languorous pans of voluptuous bodies and gory delights are the stuff that spawned this festival; early grindhouse cinema which pandered to the male libido, and now, 30 post-feminist years later, cool and hip enough to be featured on E! Channel. Wishman held court in the lobby of the Anthology, selling posters and signing autographs.

There were also plenty of "repeat offenders": Eric Brummer, director of the Hollywood Underground Film Festival with his claymation zombie gorefest, Electric Flesh; Huck Botko’s creepy Cheesecake; Annie "Super-8" Stanley’s bloody love story Hub Cap; and the ubiquitous Nick Zedd, creator of the Cinema of Transgression and chronicler of the early ’80s downtown film scene. His film, Screen Tests, a Warholian send up of juicy babes and hunky studs preening before the camera, transcended the obvious through pure performance pleasure and a punchy soundtrack.

The opening night film and winner of the Best Feature Award, Surrender Dorothy, managed to transcend the "guys-hanging-out-shooting-dope film" to be a twisted story of one junkie’s unknowing gender reassignment. Unfortunately, the film failed to deliver in its final act. Director/star Kevin di Novis’ explanation that the story was based on Nero, who after giving his wife a fatal kick in the stomach castrated one of his slave boys and used him for his sexual pleasure, was far more fascinating than the actual movie. Creating a greater buzz was Todd Verow’s feature Shucking the Curve. A follow up to Little Shots of Happiness, Shucking the Curve follows Verow’s regular lead Bonnie Dickinson as she transfers her empty obsessions from Boston to the streets of New York.

It’s really the shorts that make up the meat of the Festival, and this year’s most mind-blowing films were the ones that combined various elements of live action and stop-motion animation. Todd Downings’ Dirty Baby Does Fire Island, inspired by the crash of Flight 800, had the audience screaming in laughter at the sight of a naughty baby doll who washes up on Fire Island and discovers the sweaty pleasures of fornicating males, poppers, doll-size hallucinations and assorted types of nose candy. Winner of the Best Animation Award was Jim Trainor’s The Fetishist, a pen and ink portrait of William Heirens, the 1940s Chicago serial killer who waxed beatific on Nazi propaganda while committing crimes against nature dressed in female drag. Wig Rodeo by Marcel deJure features workers in a coat hanger factory jerking spasmodically through brute Super-8 animation and feeling like a post-apocalyptic German Expressionist revolution. And where else could you see Dyke Rat, Tony Nittoli’s portrait of a wise-cracking dyke rat left hornier-than-hell by a jilted lover.

The "Pervo-a-Go-Go!" program stood out with Lisa DiLillo’s Cockfight, an experimental video on macho bonding sports, which cross-cuts boxing and cock-fight footage. Black Oolong by David Groptell showed sexual pleasures you never imagined could be had with a teabag, and Janene Higgin’s We Hate You Little Boy cuts to the quick about parental fears, child abuse and every adult’s lost childhood

Presently Halter is expanding the New York Underground not only to include the yearly festival and completion grant, but also a monthly screening series at Void gallery starting in July. "MTV, Comedy Central, the big distributors, they all come to steal our cool..." muses Halter. "That’s cool, but our main interest is funding the types of films we want to see and creating a space to screen them."

Los Angeles Independent Film Festival

If 1997 heralded the Los Angeles Independent Film Festival as a serious presence on the festival scene, then this past spring’s edition accelerated a meteoric rise. The LAIFF has seen its audience double in size annually since its inception four years ago; last year’s 13,000 swelled to over 21,000 in 1998, and all this in the backyard of an industry notorious for leaving town to attend festivals. "There’s this incredible, vibrant heartbeat of interest here in L.A. for independent film," explains programming director Thomas Ethan Harris, who received over 1,200 submissions for the festival’s 26 feature slots (only two of which were documentaries) and 31 accompanying shorts. "I was completely overwhelmed by the outpouring of interest in films with no big stars," he added when discussing the many shows that sold out even before the festival began. "Whether it was a $15,000 feature or a multi-million dollar film, I was prepared for empty seats — and there weren’t any."

Audience members voted on their favorite films, awarding best feature to Scott Ziehl’s Broken Vessels, a riveting cautionary tale about junkie paramedics in L.A., and best director went to Rory Kelly for his L.A.-based twentysomething romance, the ensemble piece Some Girls, starring Juliette Lewis and Michael Rappaport. Best writer went to Rocky Collins for Pants on Fire, while the best short prize went to ‘Mad’ Boy, I’ll Blow Your Blues Away — Be Mine from Adam Collis. Among the 17 world premieres were Richard Sears’ pothead comedy Bongwater, Jon Reiss’ dark revenge piece about unwanted house guests, Cleopatra’s Second Husband; Bennett Miller’s documentary The Cruise, chronicling a hyper-articulate New-York bus-tour guide, and Nick Davis’ fin-de-siecle soiree flick 1999. Opening night was christened with Susanna Styron’s debut film Shadrach, based on her father William Styron’s short story and starring Harvey Keitel and Andie MacDowell.

Over 60% of the films selected for last year’s LAIFF were picked up by distributors, so it was no surprise this year to see acquisitions executives like Sony Pictures Classics’ Dylan Leiner and Mark Gill, president of Miramax’s West Coast office, in attendance throughout. "This year the films are better – in terms of production value, producers, and even sales agents," Leiner said, explaining LAIFF’s attraction for a New York executive like himself. Some would even argue that the quality was beginning to give Sundance a run for its money. "In terms of independents, you can see a definite rival to Sundance," said Marcus Hu, co-president of the Santa Monica-based Strand Releasing who since last year has considered attendance at the Festival to be mandatory. "It’s refreshing to see a marketplace for independent films in L.A."

The LAIFF also provided public screenings of somewhat uncommercial films, such as Abel Ferrara’s latest depravity-and-redemption parable The Blackout, which debuted at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival and still has yet to see a stateside release. Even though Trimark paid for domestic distribution rights, the company has been sitting on the movie ever since. "They have a remarkable ability to buy a film and bury it," heckled Ferrara at a post-screening Q&A during which the manic director strutted the aisles while answering questions and explaining how he tried, unsuccessfully, to re-acquire the rights to his own movie. One, a hard-sell film about the relationship between an ex-convict and a failed minor-league baseball player who once were childhood best friends, was all the rage at Sundance this year, but has yet to find a distributor. "I’ve been involved with 500 films in 20 years as a publicist," said Mickey Cottrell, one of the film’s executive producers. "This is the first movie where I’ve had unanimously favorable critical reviews — much of it over the moon — and all of the major distributors have passed."

Running only five days, with just two of those days having screenings that started in the morning, the LAIFF’s schedule was chock-a-block with simultaneous triple features, making it frustratingly impossible for even the most dedicated festivalgoer to actually see every one of the movies. And even the most careful plans were rendered moot by the 15-20 minute starting delays for almost every selection. Robert Faust, founder and LAIFF festival director, is already planning an expanded program for 1999: "The plan isn’t to have more films, but to accommodate those chosen," he explained with an eye towards making the LAIFF a week-long affair. "I want people to enjoy the process."

Adding considerable logistical relief was the festival’s convenient Sunset Boulevard location at the Director’s Guild of America, the first year that the Guild hosted screenings, seminars and panels under the same roof, rather the splitting them as in years past between the facilities at Raleigh Studios and Paramount. Using the DGA as its base also allowed the LAIFF to include nearby venues, like the Harmony Gold Theater, the Laemmle Sunset Five, and even the comic stand-up shrine The Laugh Factory to show screenings and hold seminars.

Among the 14 special seminars, ranging from the legal aspects of indie filmmaking to the post-production process demystified, was a spotlight on directing, which gathered filmmakers Bryan Singer and Allison Anders to discuss their craft and how they got their first films off the ground. Anders used her debut, Border Radio, as a perfect example of the independent film industry’s volatility. "None of the companies that financed the movie in 1987 are still around!" Included in Singer’s advice to directors was the necessity of a good location manager, citing his last film The Usual Suspects as a perfect example of how a keen eye in the San Diego harbor led them to change the film’s climactic set piece from a yacht to a huge mine-sweeper tanker: "It didn’t cost any more — the boat was cheap to rent and it made you think that you were watching a bigger movie."

The seminar on special effects for low-budget movies drove home the extent to which young, computer-savvy filmmakers can cut corners without compromising quality — sometimes in surprising ways and for relatively mundane reasons. Stu Maschwitz, a visual effects artist at Industrial Light and Magic, creates effects for "things I wouldn’t have money or permits to do. For me," he elaborated, "a crane shot is now a post effect."

San Francisco International Film Festival

Nicholas Cage was wrapping up the Q&A portion of his acceptance of the Peter J. Owens Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival when a woman with long dark hair came running down the aisle to shout a question at the actor. She was an actress from Romania who had read that Cage was of Romanian ancestry. Maybe they were related? And maybe they could work together on a film?

The encounter illustrates the somewhat schizophrenic nature of this festival. The oldest film festival in the Americas, the SFIFF has earned a reputation as a premiere resource for international film. This year 45 countries were represented with 174 films, and the Korean filmmaker Im Kwan Taek received the Akira Kurosawa Lifetime Achievement Award. The flip side, however is the festival’s increasing glitz quotient, exemplified by the Owens Award (last year’s winner was Annette Benning), local press breathlessly reporting Sharon Stone sightings at gala functions, and events like the Lyle Lovett "pub crawl" down Fillmore Street to promote a special screening of The Opposite of Sex.

Still, with practically no industry presence and nary a cell phone to be heard, the serious filmgoers were clearly in the majority. Films like the Russian documentary The Master’s House about Sergei Eisenstein, the six-hour documentary Fragments Jerusalem, and each of Im Kwan Taek’s films were among the most popular screenings. With such an emphasis on international films, should American independent filmmakers premiere their films at the SFIFF? It depends. American indies were fairly well represented this year, although many, like The Opposite of Sex, Gummo, Whatever, Buffalo 66, The Farm: Angola, USA and Paulina were repeats from Sundance or already in theatrical release. Only one of the festival’s six world premiere features was American — Eugene Martin’s Edge City, about class politics amongst a group of Philadelphia teens. And despite the recent explosion of independent film in this country, the SFIFF has no plans to shift its focus to increase the number of films from U.S. filmmakers.

"We are primarily interested in world cinema," said programmer Rachel Rosen, who handles the festival’s American films. To prove her point, she cites that of 200 unsolicited American films, the festival selected only one, Edge City. "With all the recent attention on American indies, and all the hype, it certainly might be easier to get funding and to get press if we [went in that direction]. But as long as distributors like Miramax keep putting out international films we’re going to continue looking for those films to show."

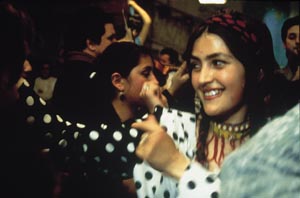

|

| Rona Hartner in Tony Gatlif's Gadjo Dilo |

Nevertheless Rosen encourages American filmmakers to submit their films, if only for the unique experience San Francisco has to offer. "What you get if you show your film here is the opportunity to show it in a completely different context [than at other festivals]" she said. "Instead of being shown with ten other American independents, it might be shown alongside a Korean film, or a John Barry retrospective. And being at the festival is a completely different experience — it’s all about the interaction with the other filmmakers and the audiences."

Although few films get picked up during the festival, Rosen said that many distributors who have seen a film at another festival will follow it to San Francisco to see how it plays for audiences. "The audiences here are real," said Rosen, "they’re very intelligent about film, the whole diversity of San Francisco is represented, and our audiences are likely to track films they’ve seen here. If something plays well at our festival, it usually does well when it opens here six months later."

Some of those stand-out films included Susan Stern’s documentary, Barbie Nation: An Unauthorized Tour, a bracingly candid look at Barbie and her outspoken creator, Ruth Handler; Jean and the Perfect Guy, a Jacques Demy-styled French musical (starring Demy’s son, Mathieu) about a sexually adventurous girl and the HIV+ boy she falls in love with, which will be released by Strand stateside; Black Tears, a documentary from the Netherlands tracing a group of Cuban musicians; and Blind Faith, a feature about race relations in ‘50s America directed by Spike Lee’s cinematographer, Ernest Dickerson. Although the modern Kabuki theater served as festival headquarters, the festival’s heart belonged to the Castro, a gorgeous single-screen movie palace where crowds lined the block for the sold-out screening of Robert Frank’s rarely-seen Cocksucker Blues, and Jeremy Irons and Wayne Wang took the stage to answer questions after the closing night screening of Chinese Box.

Also a big hit at the Castro: Gadjo Dilo, by Tony Gatlif, (Latcho Drom) a film about a Parisian man’s encounter with a Gypsy community in Romania (to be released this summer by Lion’s Gate). The film’s music so stirred the audience that a fiddler jumped on-stage for an impromptu concert, soon to be joined by the film’s star Rona Hartner, the Romanian actress who had crashed the Nicholas Cage award ceremony. She was last seen dancing on stage as the credits rolled and the audience applauded in time with the music.

Santa Barbara International Film Festival

Inheriting the job from founding artistic director Phyllis De Picciotto, Santa Barbara resident and film producer Renee Missel (Nell, Guy) expanded the 13th annual Santa Barbara International Film Festival into an 11-day showcase of over 80 features and documentaries from around the world, with 13 films being world premieres. Keeping an eye to future and the past, the festival also celebrated American filmmaking during the 1970s.

Taking advantage of the festival’s inaugural theme, "The Magnificent Seventies," Missel reserved no less than three evenings for individual salutes: director John Schlesinger (with a screening of Midnight Cowboy); Oscar-nominated Julie Christie (with a screening of McCabe and Mrs. Miller); and writer/director Robert Towne (who was honored both with a screening of Chinatown and a world premiere of his latest film, the Steve Prefontaine bio-pic Without Limits.

Missel’s vision for the festival proved to be an unqualified success for attracting audiences, with attendance up by 4,000 people to total over 30,000. Opening with Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Big Lebowski, the festival unspooled global fare including Character, Mike Van Diem’s 1998 Oscar-winner for Best Foreign Film; Luis Galvao Teles’ Elles; Ricardo Franco’s La Buena Estrella, and Iranian gems like Abba Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or-winning Taste of Cherry and Majid Majidi’s The Children of Heaven.

American Independents were well-represented with screenings of John Sayles’ Men with Guns, Tommy O’Haver’s Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss, a last-minute addition of Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters, Stuart Gordon’s The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, and With Friends Like These, Philip F. Messina’s comedy about desperate character actors in Los Angeles, which won the "Best of the Fest" audience award.

Kirsten Clarkson, director and writer of horsey, a gritty, low-budget Canadian film about heroin addicts and artists, had only praise for Missel and the way the festival was run. "She totally championed us," Clarkson said. "And the people who went to the Festival were really interested in helping out young filmmakers and young actors."

This year Missel programmed a hearty number of documentaries about films and filmmakers, including Full Tilt Boogie, Sarah Kelly’s behind-the-scenes look at the making of From Dusk ‘til Dawn; Derrick Santini’s In Ismail’s Custody, a 48-minute portrait of producer Ismail Merchant; Independent’s Day, Marina Zenovich’s snapshot of the state of independent film today; and the Turner-produced The Race to Save 100 Years, depicting film preservation techniques currently used to rescue America’s film heritage.

Complementing the Festival’s films were eight seminars on all aspects of filmmaking, including financing, directing, editing, and marketing. Indeed, some of the most heated discussions and helpful advice came from events like "Distribution Strategies," at which Sundance Festival Director Geoff Gilmore, using the 1998 Sundance winner Pi as an example, illuminated the perennial independent film dilemma of finding an audience: "I defy anyone here to describe this film so anybody would want to see it," he sighed. Producer and former Universal marketing executive Thom Mount analyzed the advantages of making a low-budget film in a small town: aside from potential perks like no-cost extras or discounts from nearby stores, the filmmakers can work with local reporters to create early word-of-mouth for their films – always crucial for winning that distribution deal. "How [your film] is perceived is your priority," he stressed. "Written publicity in non-mainstream sources, in the beginning, is more important to the studios and distributors than [being in] Premiere magazine."

During the lively screenwriters’ pow wow "It Starts with the Script," Neil LaBute wryly commented on the seating arrangements at the stage’s long table, which placed the imposing (in both presence and stature) Robert Towne right in the middle. "This has a Last Supper-y feel," LaBute remarked to great laughter. "I feel like one of the disciples here, although I sold out for a lot less." Among those seated was the Oscar-nominated Atom Egoyan, who modestly detailed the relationship he had with the cast members of his last film. "At a certain point, the actors do know more [about their characters], especially in The Sweet Hereafter. They had embodied these people, and my job then became to protect their performances."

At "The Cutting Edge," the festival’s seminar on film editing, the topic remained focused on the profound effect of non-linear, digital editing machines like the Avid. "At the end of the day, I’m not as tired as I used to be, physically," said president of the Editor’s Guild Don Cameron, whose career stretches back to Easy Rider and who reminisced about the exhaustion of working with heavy rolls of 35mm film every day. Added Neil Travis (Dances with Wolves), who, until the Avid, had once seriously considered changing his vocation because of the physical stress: "I’m a lot nicer guy as an editor – I used to get pissy with directors [when they asked for changes]." But Richard Chew (That Thing You Do!) voiced a common complaint about digital editing, which is that nowadays the post-production process, though less fatiguing, has unfortunately shrunk from six to two months. "The creation gestation period requires time," he reminded the audience.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →