LEGALIZED GAMBLING

Mary Glucksman reports on the year‘s theatrical distribution hits and misses.

Clive Owen in Croupier. Photo by Simon Mein.

What do you say about a year when a documentary about a long-dead Jewish baseball hero does better box office than all but two of the Sundance competition features? Does tiny Cowboy Booking International, the New York-based boutique distributor that worked The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg to a $1.7-million box-office bonanza know something about grassroots niche marketing its deeper-pocketed competitors do not?

Indeed, if 2000 was the year in which the established indie distributors failed at (or opted out of) the game of releasing acquired American indie films, it was also the year in which alternative distribution strategies began to pay off for microdistributors and filmmakers. Hank Greenberg is one good example, and the year’s other big surprise, Croupier, a three-year-old British film released as part of the Shooting Gallery’s innovative new film series, is another.

"This summer was very bad for films of substance," says Shooting Gallery’s Eammon Bowles. "Croupier was one of the few films out that didn’t insult the audience, and we managed to create an aura that this was something different. I doubt there’s been another film in recent years that grossed so much on such a modest ad campaign." Croupier played six months for a $6 million theatrical gross after an outside-the-box release as part of the Shooting Gallery (SG) series. The black tale of a would-be writer, from London director Mike Hodges, Croupier drew raves for star Clive Owen and ironically was a more successful release than the Warner Bros. remake of Hodges’ 1971 cult classic Get Carter, an expensive bomb that grossed just $15 million in six weeks.

Produced by London’s Film Four for about $5 million and never touted on the festival/market circuit, Croupier was coming off an uninspiring summer ’99 performance on British screens when a U.S. friend of Hodges set up the first screenings here. Bowles saw the film and its potential and slotted it into SG’s second six-film series.

In its innovative distribution approach, SG packages six films at a time, both American independents and foreign-language titles, to consolidate marketing costs and guarantees each a two-week release in 17 cities in conjunction with Loews Theaters. Corporate sponsors underwrite P&A costs, and the films open not in the familiar arthouses but in mainstream theaters such as the Loews four-plex found inside Times Square’s Virgin Megastore in New York City.

After their initial release, reviews determine whether SG orchestrates a wider release, as with Croupier, which consistently played over 100 theaters through the middle three months of its reign. Films selected for the series don’t get a big upfront payday but do participate in net profits and get guaranteed cable and video play through SG’s output deals with Starz! and Hollywood Video. All six films in the first edition, which included Sundance critical-fave Judy Berlin, played on after their contractual two weeks. SG may have another winner in their current release, A Time for Drunken Horses, the Iranian foreign film Oscar entry.

Hank Greenberg took filmmaker Aviva Kempner (Partisans of Vilna) 13 years and $1 million to make. The film first surfaced at the ‘98 Hamptons International Film festival where it won the documentary audience award. New York’s Film Forum had already booked the film for a two-week run when Cowboy International Booking co-president Noah Cowan saw it. Kempner asked the company to take the film on in a deal wherein Cowboy would receive performance bonuses based on box office.

When Hank Greenberg began what would be a six-month run last January, it was immediately clear that the hall-of-famer portrait touched a nerve no one had anticipated, bringing older Jews and baseball fans for whom Hank Greenberg was an iconic figure into theaters in droves. Cowboy was able to run with it, augmenting an austere advertising budget with a nonstop stream of free media coverage. The company embarked on a grassroots campaign to alert Jewish community centers, synagogues and other organizations to Hank Greenberg’s arrival in their area. They also restructured their deal with the filmmaker, upping their investment so the film could reach a wider audience.

"It’s very expensive to go after the mainstream," says Cowboy co-president John Vanco. "What you really need to do [with a film with obvious core audience appeal] is find everybody in that niche."

If two out-of-nowhere films were the year’s surprise specialty hits, then its most breathtaking failure had to be Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2. Artisan’s attempt to capitalize on The Blair Witch Project’s runaway $140-million success with a $10-million "sequel" turned a cash cow into a money pit. The company hired an indie director (Joe Berlinger) but rushed into production a fairly conventional script that failed to capitalize on the innovative strengths of the original. A pre-Halloween-weekend opening on a record 3,317 theatres grossed a disappointing $13 million; soon, word was out. Bad buzz? Word on Battlefield Earth wasn’t this bad! In its second weekend Book’s business fell a precipitous 62%; it fell off Variety’s top-10 list the following weekend.

The first Blair Witch capitalized on the Internet with an ingenious Web-based marketing campaign. For the second, fearful of the speed at which bad word-of-mouth travels via the Net around the world, Artisan orchestrated a first-ever worldwide release in which key territories opened day-and-date with the U.S. And although the international distributors undoubtedly paid top dollar for the film, Book of Shadow’s worldwide underperformance cripples what could have been a strong franchise for Artisan.

In the following pages Filmmaker decided to take a closer look at how seven more of the year’s most prominent indies performed in the marketplace. Call it our version of "Hits and Misses" as each release profiled here was selected to illustrate some specific aspect of today’s indie distribution environment.

THE FILM: TWO FAMILY HOUSE

Love conquers all in a 1950s Staten Island oil-and-water romance between an Italian factory worker and a pregnant Irish girl abandoned by her abusive husband. The baby is the scene stealer in this second feature from Raymond DeFelitta (Café Society), winner of the coveted Sundance Audience Award.

THE FINANCING: Producer Anne Harrison, a former development exec for Martin Scorsese reentering the film fray after seven years as an at-home mom, raised "just under $2 million" from a single private-equity source.

THE DEAL: Lions Gate’s Mark Urman and Tom Ortenberg bought worldwide rights to House within 48 hours of its first Sundance screening, beating out USA. Lions Gate offered significant gross participation with a minimal upfront payday and a 20-market guarantee; the company’s output deals will place the film on HBO and Universal Home Video. "It was a tricky situation with two very different deals on the table," Harrison says. "USA included a more conventional advance structure with [the usual] deductions from the box office. We all believed in this movie, and the ability to participate in potential gross from dollar one was attractive to our financiers."

THE DEAL: Two Family House opened on October 6 on nine screens – four in New York and five in L.A. – against tough competition from Meet the Parents, Bamboozled, Requiem for a Dream and Tigerland. Lions Gate ran TV spots in New York to supplement its print campaign. The reviews were solid across the board, but the first weekend’s box office was a disappointing $30,316 – an average of $3,368 per screen. The film did particularly poorly at the New York megaplex Sony Lincoln Square. Lions Gate pulled back on advertising, and the film’s financiers – who, after all, had turned down a higher advance in favor of the box-office gross – bought the second weekend’s ads themselves.

THE OUTCOME: House expanded to 65 screens on its fourth weekend out and made $964,541 in ten weeks. It should gross over $1 million.

WINNERS AND LOSERS: A mixed bag all around. The film’s gross is more than respectable, but the investors’ recoupment hopes will most likely lie with the effectiveness of Lions Gate’s foreign-sales arm.

THE FILM: DARK DAYS

Who would expect that an ultralow-budget black-and-white documentary about New York City homeless people living in abandoned train tunnels would become one of this year’s sleeper hits? The ride began at Sundance, where first-time filmmaker Marc Singer won three top prizes, the Fest’s Audience, Cinematography and Freedom of Expression awards.

THE FINANCING: The film was five years in the making on minimal cash. Singer drafted his subjects as crew (one laid track and they all knew how to tap power) and gave up his apartment to live with them. Cinevision coughed up a loaner 16mm camera, and Kodak donated stock; maxed-out credit cards took the film through post.

THE DEAL: Five months after Sundance attorney John Sloss brokered a mid-six-figure deal for North American theatrical, Internet and video rights with Palm Pictures, its online partner, sputnik7.com and Wide Angle Pictures; the Sundance Channel got television rights in a separate deal.

THE DEAL: Sweet. Alt-culture p.r. firm Nasty Little Man, aided by the film’s DJ Shadow score, scored massive free publicity, placing Singer everywhere from Vanity Fair to People to Spin. Clips and interviews streamed on sputnik7. Opening on a single screen at Manhattan’s Film Forum, Dark Days did $42,000 in its Labor Day-weekend release.

THE OUTCOME: $309,648 in 13 weeks on six screens.

WINNERS AND LOSERS: Singer and Palm both scored with this successful documentary.

THE FILM: GEORGE WASHINGTON

A lyrical debut from writer/director David Gordon Green about kids in the South. Inexplicably rejected by Sundance, the film premiered in the Panorama section of the Berlin Film Festival and went on to win awards at Newport, Atlanta, Edinburgh, Toronto and Torino. And, after being turned down by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and MoMA’s New Directors/ New Films series, it was later selected for the New York Film Festival.

THE FINANCING: Shot in 35mm Cinemascope, gorgeous George looks like it cost way more than its scraped-together, low-six-figure microbudget. The film was privately financed through individual investors.

THE DEAL: Producer Lisa Muskat arrived in Berlin with a wet print and a mission: to convince sales agent Christa Saredi to rep the film for international. Saredi took some convincing to make room in her heavy schedule to see the film. She did, though, and sold the film to France’s Opening. Other deals, including a U.K. sale, are in progress. A distributor screening in New York yielded both extravagant praise and consensus that George Washington would be difficult to market. Cowboy Booking picked up the film, making it the first through its "Code Red" partnership with producer Jeff Levy-Hinte, who invested P&A funds in a 10-film Cowboy slate. The filmmakers received a low five-figure advance.

THE DEAL: The reviews were unbelievable. Ebert and Rolling Stone raved; Time handed over a full page. But the New York Times’s policy of not rerunning New York Film Festival reviews (in this case, Elvis Mitchell’s career-making rave) hurt. (Mitchell made up for it by citing George Washington as his second best film of the year.) Cowboy countered by quoting all the raves in a large opening-day ad. The film opened on five screens – New York’s prestigious Lincoln Plaza as well as downtown’s Screening Room, which Cowboy books, and three New Jersey screens – and will play 75 markets by summer, Cowboy’s John Vanco says.

THE OUTCOME: Slow and steady in an uphill race. Opening pre-Halloween against 10 other indies plus Blair Witch 2, George Washington pulled in an okay $11,847 in its two Manhattan spots while tanking in Jersey, thereby hurting its important opening-week per-screen average. George went on to open strong in L.A.; the total gross after five weekends out was $58,260.

WINNERS AND LOSERS: With George Washington showing up on multiple year-end 10-best lists, Green is the big winner here. The losers? Every other risk-taking American indie. If a film this well-reviewed can’t turn into a commercial hit, what hope is there for the next truly innovative narrative-feature filmmaker?

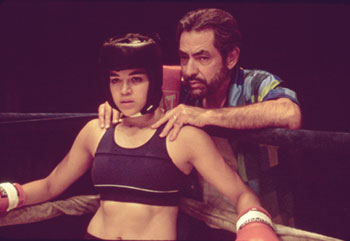

THE FILM: GIRLFIGHT

Feisty Latina from the projects finds grace, glory and a boyfriend in the boxing ring. Its Sundance premiere yielded a Grand Jury Prize (shared with You Can Count on Me) and an award for director Karyn Kusama. The film was selected for Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight, and it won an award at Deauville.

THE FINANCING: Kusama had been director John Sayles’ assistant for several years when he offered to invest in her debut feature. Ultimately, Sayles put in $750,000 and the Independent Film Channel $350,000.

THE DEAL: After the only bidding war of note at last year’s Sundance, newbie Sony division Screen Gems beat out Fine Line, Miramax, USA and Paramount Classics for domestic rights at a cool $2.5 million –plus, sources say, a good back-end deal.

THE DEAL: With star Michelle Rodriguez scoring all the Latino and indie-film magazine covers as well as TV appearances on Charlie Rose, Leno and Kilborn, the film turned out to be a magazine editor and TV booker’s dream. Screen Gems, which was created by Sony to fill the gap between Sony Classics and Sony Entertainment, opened two screens in New York on September 29 and expanded to 253 the next weekend, supported by TV spots and full-page New York Times ads. Forget opening small and building an audience – Screen Gems went immediately for the mainstream.

THE OUTCOME: A rude surprise. Glowing reviews and ecstatic festival audiences seemingly spelled an instant hit, but the public didn’t buy tickets, embracing instead Billy Elliot as the fall’s underdog-triumph movie. Box office dropped steeply in the third week, and Screen Gems cut its New York Times advertising. Girlfight staggered a few more rounds, grossing $1,523,941 in eight weeks.

WINNERS AND LOSERS: Rodriguez and Kusama are big winners; non-pro Rodriguez has already been cast in several other features. And the investors scored as well, cashing out with a profit before the film hit the theaters. The losers? Screen Gems and its "between the mini and major" releasing strategy. Insiders questioned its costly advertising and releasing campaign, which didn’t target any particular audience. Even with the ancillaries, it will be hard for the company to recoup its advance and high-seven-figure marketing campaign.

THE FILM: LOVING JEZEBEL

A by-the-numbers romantic comedy about a fool for love who only falls for other guys’ girls. This Love Jones-wannabe was Kwyn Bader’s first effort at directing (he wrote the 1998 cable feature Tuskegee Airmen). The film premiered at New York’s Urbanworld Film Festival in August 1999 before winning South by Southwest’s Audience Award the following March.

THE FINANCING: The low-budget pic was fully financed by Encore Cable division Black Entertainment Television Movies (BET), a new channel programming African-American films around the clock under the Starz! umbrella.

THE DEAL: In a lockbox somewhere. The Shooting Gallery added Loving Jezebel to its roster in December 1999 after signing a long-term output deal that gave Starz! exclusive pay-TV rights to all its features. Meanwhile a Shooting Gallery pact to send up to four films a year out through Universal Focus, Universal’s fledgling specialty division, kicked in, and Jezebel wound up as the first release.

THE DEAL: Jezebel arrived with little warning on an overcrowded pre-Halloween weekend in a 74-screen release the film’s minimal ad campaign couldn’t hope to support. Dismissive reviews didn’t help. What’s puzzling is that Bader, a former marketing staffer at Arrow, couldn’t spin himself a press profile.

THE OUTCOME: The film dropped to 25 screens by its second and last weekend, pulling in a dismal $223 average. The total gross for those two weeks was $69,470.

WINNERS AND LOSERS: There are no real winners here, although Starz! and BET got a highly promotable property for their cable channels. And Bader used Jezebel to get the word out about his next film, a love story between a jazzman and a ballerina in wartime London, Paris and Harlem.

THE FILM: THE TAO OF STEVE

A romantic comedy with Donal Logue as the Gerard Depardieu of Santa Fe, a jerky overweight guy who women adore. Copy editor’s nightmare Jenniphr Goodman, an NYU film grad, directed from a script written with her actress sister Greer, who also plays the girl who gets this guy for good.

THE FINANCING: The Goodman sisters had been working this one themselves for several years before they got Good Machine and partner Anthony Bregman (Love God) onboard to produce. The film was made for $1.25 million raised from private-equity sources.

THE DEAL: Logue won a special acting award at Sundance, and Sony Pictures Classics took domestic rights for a typically modest advance two weeks later. No one has a better reputation than Sony for mindful, exactingly calibrated releases that maximize playdates while conserving marketing costs to return a profit to both company and filmmaker. Canal Plus took the rights to France, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and the Benelux region.

THE DEAL: "Use the media" is Sony’s mantra, and the loquacious Goodman sisters were good copy, as was Logue, who broke out in this role after appearing in scores of Hollywood supporting parts. Good reviews helped too.

THE OUTCOME: Steve benefited from its August 4 opening during the Republican National Convention, when a little comic relief was just the ticket. Its first nine-screen weekend pulled in $93,000, and the film passed the $1-million mark in four weeks, hitting its widest release – 189 screens – a month later.

WINNERS AND LOSERS: Sony Classics, which officially replaced Miramax as the Holy Grail for filmmakers looking for a deal at Sundance 2001. And the Goodman sisters should have no trouble financing their next feature.

THE FILM: URBANIA

Dan Futterman (Judging Amy) stars in a dark New York tale of homophobia, grief and redemption. Shot on film, Urbania’s footage was transferred to video, where its images were manipulated before going back to 35mm, resulting in a strikingly unusual look.

THE FINANCING: A lean $500,000, raised privately by producer Stephanie Golden and director Jon Shear.

THE DEAL: Selected for the Sundance Competition, Urbania was largely overlooked at the fest. Weeks later, the filmmakers sealed a U.S. deal with tiny Unapix that included a $100,000 advance and a $250,000 P&A commitment. "Other companies were interested but hedging," Golden says. "Films get stale quickly, and we didn’t want to wait." Pre-release, Urbania heated up with awards at gay-and-lesbian fests in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Provincetown and Philadelphia. But only two weeks before the film’s September 8 opening, Unapix called Golden with bad news: they didn’t have enough money to release the film. Urbania was back in play. Two days later Lions Gate stepped up with their second rescue of the season. (They also grabbed But I’m a Cheerleader when a Fine Line deal fell through.) Lions Gate didn’t offer an advance but would match the Unapix P&A numbers and secure a video deal. Meanwhile Blackwatch tied up Canadian and international rights for a $100,000 advance.

THE DEAL: Lions Gate put Urbania out on 10 screens on September 15, four each in San Francisco and L.A. and two in New York, where the film got New York Times ads its first three weeks. And Golden mounted an unusual grassroots e-mail campaign, with regular alerts to film societies, colleges and gay-and-lesbian organizations.

THE OUTCOME: The reviews were stunningly good across the board, and Urbania grossed $1 million off 87 playdates in nine weeks. "There’s a lot of product out there chasing eyeballs," Golden observes. "We were lucky in having the gay market as an obvious target audience."

WINNERS AND LOSERS: You do the math. A surprise critical winner that successfully found an audience, Urbania has made back just 20 percent of its negative cost for its investors two years after wrapping in December 1998. Lions Gate easily covered its costs, however, and Sher and Golden aren’t complaining – Urbania put them on the map.

Sidebars:

Jonathan Bing on indie film dealmaking &

Mary Glucksman tallies the grosses

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →