Now in its 21st year, the Palm Springs International Film Festival Festival (Jan. 5-18) continues to be the place to be seen for foreign film Oscar contenders, 41 of which screened in this year’s Festival. U.S. films, for the most part, take a distant back seat, since most serious American filmmakers don’t want to risk of alienating the Sundance Film Festival, which comes on the heels of Palm Springs and insists on its films being U.S. premieres. While there were a smattering of U.S. indies, the majority would never be confused with Sundance entrees, except for the very fine

The Most Dangerous Man in America, the Daniel Ellsberg doc (and likely Oscars favorite) that was my favorite film in the four days I was here. But more on that in a bit.

Compared to the hipster flash of Sundance or the frenetic marketplace that is Cannes, PS flies under the radar, close enough to L.A. to preserve an aura of Hollywood glamour, far enough to remain unspoiled by the elitism that can pervade in New York or Venice. With its azure desert skies and well-heeled senior demographic, PS is normally a placid experience. This year, however, controversy intruded on the proceedings, as the festival found itself in the middle of a diplomatic imbroglio.

Early last week, the festival’s executive director, Darryl MacDonald, received a call from the Chinese consul in Los Angeles, asking that the festival not show the documentary

The Sun Behind The Clouds, about Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

“I explained that it was a foreign co-production, not just Tibetan,” MacDonald recalls. “They said, ‘you can’t play this film because it’s not accurate. It purports that Tibet is being suppressed by China – even your own government agrees that Tibet is part of China.”

MacDonald was not about to let a foreign country dictate what he could and could not show at his own festival. “I said, this is a question of freedom of expression,” he says. “It’s an artistic event, not a political event.”

MacDonald refused to pull the film. Days later, the Chinese filmmakers behind the country’s two PSFF entries,

City of Life and Death and

Quick Quick Slow, sent regretful emails announcing they were withdrawing their films.

“This has never happened at any festival I’ve been a part of,” MacDonald says.

An emergency meeting was convened with the consul. MacDonald asked him how he would feel if, say, the Japanese government requested that City of Life and Death – a film about Japanese atrocities committed during their occupation of the Chinese city of Nanking in 1936 – be withdrawn because the Japanese might feel it’s biased. “But that film is the truth!” the consul reportedly exclaimed. “The Tibetan film is full of lies!”

The consul also assured MacDonald that it wasn’t the Chinese government that elected to pull its films, but the filmmakers. Uh-huh. And if you believe that, you believe that Mark McGwire took steroids to improve his health, not his strength.

To show their support for MacDonald,

Sun Behind The Clouds directors Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam flew in from India to be at the festival for the film’s presentation. According to MacDonald, “they found it ironic that the Chinese, who always complain about U.S. interference in their politics, had no hesitation about interfering with a film festival.”

On the lighter side, the festival’s annual Black Tie Awards Gala, which honors Hollywood actors from the year’s best films, was highlighted by Mariah Carey’s drunken acceptance speech for Best Breakthrough Performance for her role in

Precious. Standing onstage with

Precious director Lee Daniels, Carey delivered a loopy five-minute ramble caught in all its glory by TMZ, and viewed by some 1.8 million on YouTube.

At least this was something MacDonald could laugh off. “Because this awards show isn’t televised, and takes place outside of Hollywood, it presents an opportunity for talent to let their hair down,” he says. “Anything can happen here.”

After the opening night presentation of a proper Oscars contender,

The Last Station, the Festival got down to business. With 191 films unspooling from more than 70 countries, and as many as six or seven films showing at a given time from morning till night, the choices are agonizing, and I frequently found myself lamenting films I had missed. (“You didn’t see

Airdoll?” a Festival volunteer exclaimed, referring to Japanese director Hirozaku Kore-eda’s film about an inflatable sex doll come to life. “That’s the best film here.”)

No, I didn’t see

Airdoll. Instead, a critic friend and I kicked off the first day of competition with a jam-packed screening of

The White Ribbon, Michael Haneke’s starkly beautiful-but-creepy study of strange goings-ons among the children of a rural German village in the days leading up to World War I. Gorgeously shot in vivid black-and-white by Christian Berger (already cited as Best Cinematography by the New York Film Critics Circle), even the leisurely-paced scenes (of which there are many) seemed cloaked in menace and foreboding. The film resolves few of its narrative mysteries, but chillingly foreshadows the devastation to come once these children grow up to become the adults of 1933-45. I left the film feeling grateful to have not grown up in a strict German household.

The Luxembourg/Swiss co-production of

Draft Dodgers may conjure up memories of Vietnam, but in fact, is a coming-of-age story about a young engineering student in Nazi-occupied Luxembourg who, rather than be conscripted and sent to the front lines to fight the Allied forces, hides out with a group of “draft dodgers” in the underground mines. The men are suspicious of the student, whose father was a Nazi collaborator. The debut feature from theater director Nicolas Steil, it presents audiences with a “what would you do?” series of moral questions, and examines the qualities that define heroism, and the sacrifices required.

Later on, my critic friend rejoined me for the Danish film

Terribly Happy. Five minutes into the film, he bolted up in his seat. “I’ve seen this,” he muttered. “I saw it at AFI. You’ll like it,” he said, as he made his way out. “It’s quirky, like the Coen Brothers.” And indeed - it is. The premise is reminiscent of the British film

Hot Fuzz, where a cop from the big city (in this case, Copenhagen) is given “punishment” duty in an undesirable province. The similarities end there, however: the Danish town is full of secrets, and outsiders who can’t adapt often disappear, with a nearby bog as evidence. Director Henrik Rubin Genz fashions a nourish dark comedy with overtones of

Blood Simple, as the poor cop – who’s hiding a secret of his own – gets inextricably caught up in the town’s corruption and deceit.

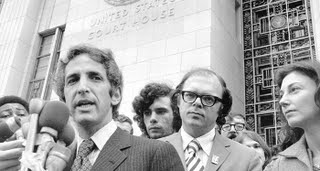

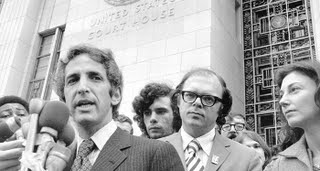

Saturday morning kicked off with

The Most Dangerous Man in America (pictured above), the engrossing story of Daniel Ellbserg’s startling transformation from Pentagon wonk to anti-war activist, after his increasing disillusionment with how the American public was being lied to about what was really happening in Vietnam. (Sound familiar?) It led to a crisis of conscience that resulted in one of the landmark freedom-of-the-press cases in history - Ellsberg’s decision to turn over the Pentagon Papers to the

New York Times in July 1971.

After the film ended, Ellsberg walked out on stage to a standing ovation, and when the first question came about how the film compared to modern-day events, Ellsberg wasted no time venting his unhappiness with the current Administration. “We should be out of Afghanistan,” he pronounced, then went on a spirited analysis of how Lyndon Johnson and Barack Obama were both “smart men leading us into the same dangerous pit when it comes to war.”

Opting to end the day on a fluffier note, I went for a French-Canadian buddy-cop comedy from Quebec,

Fathers and Guns, that’s already been acquired by Sony for an American remake. Directed by Emile Gaudreault, it’s about the antics of a father-and-son undercover cop team who go on a weekend retreat to entrap the defense lawyer of a notorious biker gang leader, while also working out their (predictably) dysfunctional relationship. I can only hope the Hollywood version will be a lot funnier, but I’m not holding my breath.

I wanted very much to like

Ajami, an ensemble drama, co-directed by Israeli Yaron Shani and Palestinian Scandar Copti, that’s been likened to a Middle Eastern

Crash. The filmmakers talked at length about the challenges of making the film, set inside the Israeli city of Jaffa, at a Talking Pictures seminar on Sunday morning. The film took seven years to make, and was shot with an all-amateur cast that the filmmakers trained for a year, using improvisation and role-playing techniques. They spent 14 months editing 80 hours of footage.

According to Shani , it’s the first Israeli film that’s brought Arab audiences into Israeli cinemas. Adds Copti, “It’s a rare chance for Palestinians to see themselves from the outside.”

Yet despite their honorable intentions, Ajami falls flat. Like

Crash, the film interweaves multiple storylines, and jumps back and forth in time to reveal new perspectives on the same event, forcing audiences to reexamine their own perspectives. But the similarities end there. The film is undone by a tedious middle section in which the story grinds to a halt, and the characters’ motives become unclear. It was almost impossible to distinguish Christian from Muslim from Jew, which, while admirable from a humanist standpoint, proved frustrating when trying to follow the disjointed narrative.

What the film lacked in dramatic tension, it more than made up for in the inflammable Q&A after, when several audience members took exception to Copti’s observation that Arabs living inside Israel felt like second-class citizens, and another questioner asked the filmmakers what they “planned to do” to end the cycle of revenge and violence – a question that no one in the Middle East has been able to solve for the past 80 years or so.

Finally, there was

Transmission, a post-apocalyptic Hungarian film about a world where televisions and computers have stopped working, and a population deprived of its TV and Internet fix slowly descends into chaos. Directed by Roland Vranik, it’s alternately mesmerizing and maddening. It reminded me of those old Budweiser Dry commercials, when a plaintive voiceover asked, “Why are foreign films so… foreign?” There are no easy answers and not every storyline is paid off. It’s told from the point-of-view of three brothers, and the film is at its best when focused on Henrik, a madman/artist who’s had insomnia since losing his beloved TV, and finds an ingenious method to recreate the viewing experience. One form of communication will be replaced by another, Vranik seems to say; if the projector had shut off and the film had stopped in the last reel, I wouldn’t have been the least bit surprised.

Heading back to L.A. on I-10, I contemplated what I had seen. I hadn’t been blown away, by any single film, but I’d seen some pretty thought-provoking ones, and had only walked out on one: an incomprehensible Greek movie,

Dogtooth, that I’m sure will have its revenge on me when it becomes one of the five Oscar-nominated foreign films. International cinema is alive and well in Palm Springs, and if I didn’t always understand exactly what I’d seen, that was OK too. At least I was still thinking about it the following day, something which happens all too rarely in mainstream Hollywood.

Labels: Festivals

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/15/2010 10:04:00 AM