Back to selection

Back to selection

“This Is the First Film Todd and I Filmed Digitally”: DP Ed Lachman on Dark Waters

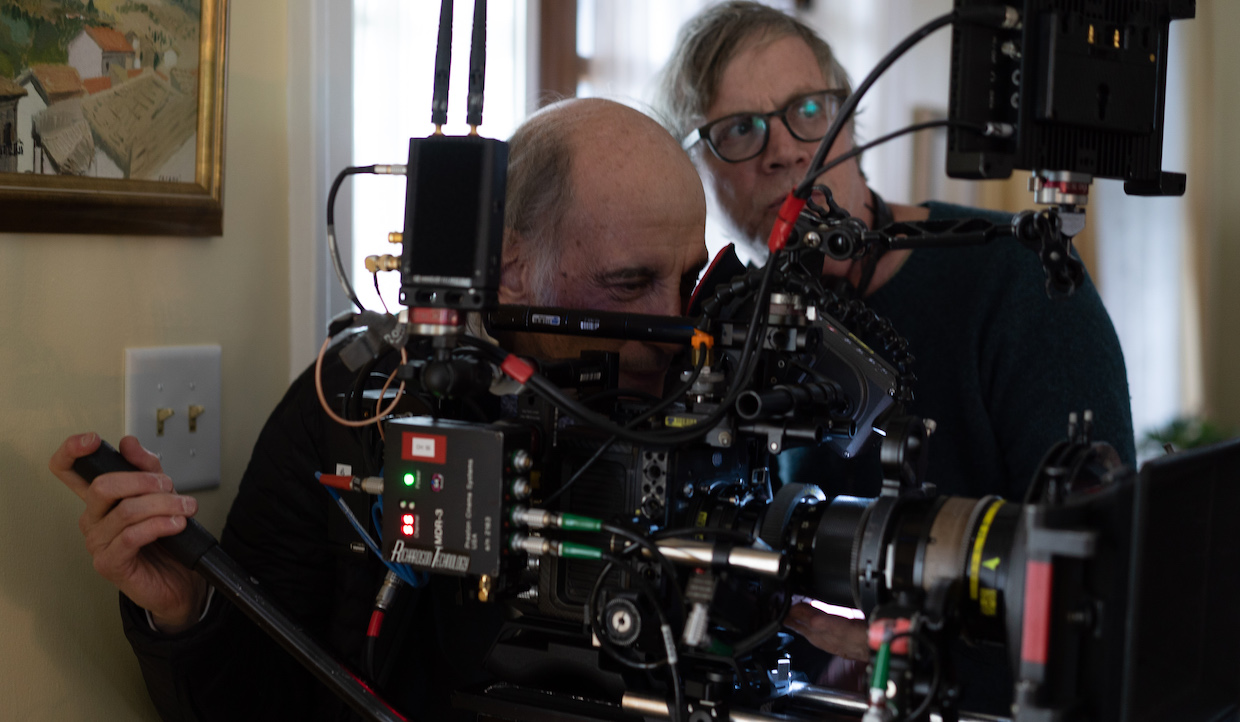

Ed Lachman and Todd Haynes on the set of Dark Waters

Ed Lachman and Todd Haynes on the set of Dark Waters Starting with 2002’s Far from Heaven, cinematographer Ed Lachman worked with director Todd Haynes on four features before this year’s Dark Waters. Based on a true story, the movie follows corporate attorney Rob Bilott (played by Mark Ruffalo) as he investigates industrial pollution on a farm in Appalachia. The case widened to include the entire town of Parkersburg, West Virginia, and led to a years-long lawsuit against DuPont. Lachman spoke with Filmmaker at Camerimage, the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography, held this year in Toruń, Poland.

Filmmaker: How did you and Todd approach this story?

Lachman: In his storytelling Todd has always dealt with how our culture treats the outsider and insider. The difference is now we’re all the outsiders. He was drawn to the project by how we’re all being contaminated, both figuratively and literally, by political, social, and ecological issues, and in our health.

It was something that Mark Ruffalo brought to Todd. Todd usually originates his own projects, but he felt connected to the story. Todd had previously made Safe, about a woman whose life is debilitated by symptoms of an unexplainable environmental illness. I had done Erin Brockovich, which dealt with caustic damage to the environment and people’s lives. So this was the project we both felt committed to.

In researching, we looked at “whistleblower” films from the ’70s, those paranoiac thriller movies like Klute (1971), The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976) that Alan Pakula and Gordon Willis created, and later Silkwood (1983) by Mike Nichols and Miroslav Ondříček.

Interestingly, Todd also exposed me to Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), the original version directed by Don Siegel. What I found interesting about the narrative idea was that Siegel and the writer Daniel Mainwaring said that they didn’t see the film as a political expose or metaphor of Communism or McCarthyism at that time, however you might see it now. The movie tracks in a similar way how our bodies are being invaded or taken over by some exterior force. Today it’s no longer fiction: our bodies are being taken over by Teflon, or, in Brockovich’s case, the insidious contamination by PG&E to a community.

It was interesting to look at Dark Waters as a modern-day horror film, and then look back at how visually Pakula and Willis would let viewers fill in what they saw observing social systems. Willis’ static proscenium, his layered frames inform a visual landscape of observation much like our character, lawyer Rob Bilott, is in the process of doing.

Todd also talks about the story as a procedural, where watching the process unfold is compelling even if we know the outcome. In its study of the investigation, but more importantly that of Rob’s transformation, you feel the cost of what it means to go up against the systems of the power. You feel his isolation and loneliness, how it changes his relationship to his work, family, community and the world.

In our story, there is a sense of peril, vulnerability and destabilization facing all the characters, the farmer Wilbur Tennant (played by Bill Camp), the community of Parkersburg, West Virginia, Rob’s wife Sara (Anne Hathaway), and ultimately ourselves.

When I was approaching the visuals, I was looking for ways to show how the images would become toxic and contaminated. There is also an overall coolness in the film, literally in the weather but also in the emotions of the story. I implemented a yellowish-green hue motivated by practical lighting inside the law firm, hospital and homes that would contrast to the exterior coolness of weather and environment. It fit the temperament of the characters in their psychology and stoicism.

We shot Dark Waters in Cincinnati where the story actually took place, and in the Appalachia of southern Ohio and West Virginia where we shot Carol. I also went to school in that area where I attended Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, so I was familiar with the area and the people.

Filmmaker: That’s one sad looking farm you found for Wilbur.

Lachman: We’re not there just to make pretty pictures. For me, it’s how you find the images that embody the metaphor and spirit of the story.

Filmmaker: It’s a hard enough life, and the fact that they were being poisoned without knowing it is the crime the film illuminates.

Lachman: It was done to all of us. In the case of Parkersburg, West Virginia, which was Ground Zero for this case, when they took blood samples of 70,000 people, everyone had traces of C8 in their blood.

Filmmaker: As the film points out, DuPont seemed like it was too big to fight, so it did what it wanted.

Lachman: They were allowed to self-regulate themselves at that time, outside of the EPA. That’s what ultimately entrapped DuPont, because Rob could use their own documentation against them.

Filmmaker: You had to find a visual way to convey a lot of information. There’s a lot of data to get across to viewers.

Lachman: That’s what was interesting, how do you make that engaging? So there’s a certain visual landscape that the camera has observing the characters and Rob’s process. Todd speaks about this type of genre of thriller, which is about people working within and against the system. How space is important in the storytelling, how the static, layered frames allows viewers to have a sense of objectivity in their discovery. That restraint and that objectivity of the camera was Rob’s process in his discovery. We don’t allow the whole puzzle to be put together at once, but allow the audience piece by piece to connect to what the real story is.

Filmmaker: It’s very easy to follow the story visually despite the difficulty you had shooting it. I’m thinking of the scene at the Chemical Alliance dinner, where you have a big, ornate room, what looks like hundreds of extras, and yet you have to focus on this conflict between Rob and DuPont lawyer Phil Donnelly [played by Victor Garber].

Lachman: The hall of mirrors room at the Hilton at Cincinnati. Again, what is the story you’re telling between the characters? Victor Garber’s and Mark Ruffalo’s character, what’s dramatic in the storytelling of their exchange is the tension between them, while the other characters have their own reactions to it.

Filmmaker: But you still have to light it.

Lachman: That brings up another whole issue. This is the first film Todd and I filmed digitally. We wanted to shoot it in film, because the story is about contamination of chemicals and how they affect our lives. We did tests and I proved to Participant Media that film was cost effective, but there was such pushback. The depth of grain and the way colors are created in the negative I find very difficult to recreate in digital capture. The story also takes place from the ’70s until today, which was another reason we wanted to shoot on film, the way the world would have been seen back then. Today most studios, maybe because the people who are in control are younger or don’t want to deal with the film process, will give you excuses like, “You could have scratches,” or “You’re going to have a delay in seeing the dailies, getting them from Cincinnati to New York and back.” Which is maybe a day. I mean, people have been making films for a hundred years that way and it’s always worked.

I wanted, and Todd wanted, to shoot the film through photochemical means, because we’re saying something about the chemical makeup of the world. Ultimately, Todd didn’t want to make this his fight, and he trusted that we could film digitally.

Filmmaker: Ironically, Kodak at one time was a large contributor to chemical pollution.

Lachman: At one point that was one of the arguments that Participant Media made. Kodak is more than aware of that and is more than actively ecologically conscious today. So, the decision Participant made was more about the immediate gratification of digital media and not the aesthetics of the look.

I did everything possible to deconstruct the image by using older lenses. I used my older Speed Panchros, older zooms, Angénieuxs, 20-60, 20-100 Cookes and the Canon K-35s. I played a lot with mixed lighting and also color temperature with camera settings. This is what I do with film stocks. I might shoot a daylight stock in tungsten light or a tungsten stock in daylight. So I played the same way with the Arri Mini.

Filmmaker: You’ve explained your influences and your approach to Dark Waters. What would be the ideal reaction you’d want from viewers?

Lachman: Hopefully our film has a sensibility of the ’70s American filmmaking, where there is a challenging narrative between the cinema and audience. The movie doesn’t resolve the conflict with a simple solution to corporate corruption and greed, but it engages each of us to have a responsibility to take a position against it.

Rob Bilott believes that the system should work, he believes in the integrity of give and take between industry and government, between regulation and profit motives. He has a sense of questioning, questioning authority, questioning dogma, questioning orthodoxies. We need to think the same way.