Back to selection

Back to selection

“Feels as if Time Is Unspooling in Front of Our Eyes”: Editor Gabriel Rhodes on Time

Time directed by Ursula Garrett Bradley

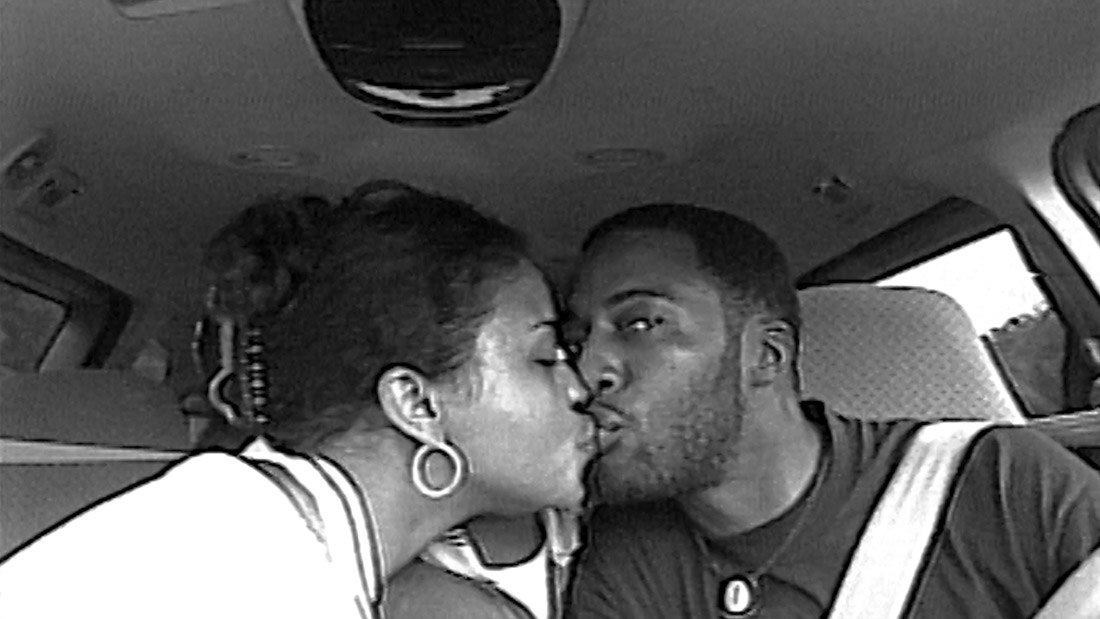

Time directed by Ursula Garrett Bradley Fox and Rob Rich are married, but they’ve been apart for 21 years—Rob is currently serving a 60-year sentence for a crime that they both committed. Fox has been diligently fighting for the release of her husband, while also filming home footage to share with Rob so he can watch his six children grow and observe the home life he cannot be a part of. Garrett Bradley’s documentary feature debut Time explores the violent oppression of African American people entrenched in America’s prison system and editor Gabriel Rhodes elaborates on the process of weaving archival, home and interview footage together to perfectly fit Bradley’s artistic vision.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Rhodes: Garrett saw a film I had worked on called Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. at Sundance in 2018 and she reached out to me based on our use of archival in that film. Similarly to Time, it had a lot of personal footage that was repurposed to form a central narrative for a feature documentary.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Rhodes: As a filmmaker who straddles the documentary and the art world, Garrett has such a unique aesthetic sensibility. So, the biggest goal was to provide the film with a structure akin to a traditional narrative documentary while retaining Garrett’s lyrical instincts.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Rhodes: Garrett and I were invited to bring Time to the 2019 Sundance Edit Labs and while we were there, we screened the first edit of the film. At that point, I had worked on it alone for about 2 months, taking my cues from the footage. That cut had a very logical narrative arc to it but it felt like it was lacking Garrett’s voice and was relying too much on the primary “interview” (a filmed speech at Tulane University). We spent a lot of time at the Labs linking back to raw footage and watching whole uncut scenes with our lab mentors. Many of these scenes found their way into the film in their uncut versions, which helped to redefine the pace of the film and helped us to retain Garrett’s aesthetic.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Rhodes: I started out in the mid-90s managing a post-production house in Berkeley. Avids were a recent invention and they were very expensive to get access to. But the owner of the facility allowed me to use them at night for projects that couldn’t afford commercial rates. So that’s how I cut my teeth and started editing feature documentaries. Along the way, I’ve learned so much about storytelling, style and structure working with great directors, like Amir Bar-Lev, Fisher Stevens, Kim Snyder and Garrett Bradley. I learn something from every film I work on and hopefully apply the lessons learned to the next one.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Rhodes: We cut Time on Premiere, which was the first time I’d used Premiere for a feature. I really like the Premiere interface and find it very user friendly, so I was excited to use it for a full-length project.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Rhodes: Our first pass for the ending of the film felt flat and unmotivated and we knew we had to elevate it emotionally. Garrett had an idea that she expressed as: “Play the entire film backwards,” so I actually tried that. Unfortunately, seeing interviews and verite in reverse felt awkward. However, some of the archival played really nicely in reverse. So I went through all of the archival footage we had, looking for shots that would play well backwards and give a sense of kinetic rhythm. The result hopefully is a sequence that feels as if time is unspooling in front of our eyes.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Rhodes: There is so much about this family and their situation that was educational for me. Their lives have been impacted forever by Rob’s incarceration and the more time I spent with the footage, the more I empathized with their pain and frustration. And the more time I spent with Fox’s home archival, the more I saw how profound the small moments were. Fox visiting her children at school or a birthday celebration—these moments were infused with 20 years of perspective, so those little moments now have an incredible gravity to them.