Web Exclusives  Friday, January 30, 2009

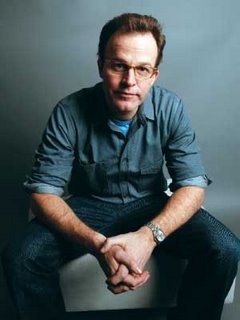

POSITIF'S MICHEL CIMENT

By Jamie Stuart

In connection with the Film Society of Lincoln Center's new series "Mavericks and Outsiders: Positif Celebrates American Cinema," Jamie Stuart spoke recently with Positif's editor, the noted French film critic and author Michel Ciment.  FILMMAKER: FILMMAKER: I probably know you best from your Kubrick book. What was that like, having the ability to interview him over the years? CIMENT: Well, it came very naturally. I don't know why. I think he had a piece of mine translated from 1968 -- a long essay I did on the work of Kubrick. It was probably the first essay in France to try to show the strands of Kubrick's work and the connections between all the films. People were always skeptical about the unity of his work; he was changing all the time, his style and form and so on. I was on the list of people he would approve to do interviews with on A Clockwork Orange. He liked what I did. He liked the interview. He liked the conversation. He would call me regularly for information on various things he wanted to know: Distribution in France, exhibition, technical things, people who could help him and so on. And then, I met him regularly -- I was not a friend of his, I don't think anybody was really friends with Kubrick -- but he was not at all aloof, he was extremely charming. I found him one of the best people to interview, though of course it was a little intimidating because you'd have such a short time. But he was very professional. We'd talk quite a lot on the phone, that's true. And then, I wrote this book in 1980. My wife said Kubrick called, he'd got the book. He called me back at 9 in the evening and said, "I received your book. It is the most beautiful book I have seen on a film director. I would like to order 400 copies, if you could get me a price." There's not much else to say, except of my fascination with Kubrick's work. But it went on quite easily. I think he knew my book on Kazan; he was a great admirer of Kazan. I did a book with Joseph Losey; he knew Losey too, and Losey was a great fan of Kubrick. I think the fact that I was a professor -- I was teaching at the university -- I think he appreciated that. I think he was a little suspicious of the press in general. He'd had bad experiences: Interviews that had been published without his approval, or they'd say things that he didn't really say. So I think the fact that I was a scholar, for him, it made him more respectful. FILMMAKER: What makes Positif different from other film magazines? CIMENT: Well, I think, first of all, it's part of history now. It started in '52, like Cahiers du Cinéma, in '51 -- two magazines with more than half a century of life. I think it's also a magazine which has established a very strong relationship with directors, because I think they felt that we were not conditioned by ideology or by clannishness, and so on. It's a magazine that is fueled by a love of cinema. We are not poseurs trying to be Maoist or structuralist. We really react with a passion for film. After that, of course, we exercise our intellectual curiosities to analyze the films. But before that, our first reaction is not to wonder how we'll look if we like a certain film: Can we like American films while the Vietnam war is going on? Can we like this film which is telling a story when it is the end of the story in films? As Godard said, "We can't tell stories anymore." We have never been into this thing which makes magazines very popular among intellectual circles, because it's always flattering to say, I am intolerant, or, I believe in this. We have never been -- even if we are accused of eclecticism -- we don't care. What fuels us, again, is this love of cinema, curiosity, openness toward foreign cultures. The magazine was known in the '50s for looking for new directors from Czechoslovakia, Poland, and later, in Brazil. The next issue is about new Belgian cinema. It is open to new forms and styles, and at the same time to study the past -- to make connections between the past and present, commercial cinema and sometimes very peculiar types of cinema. As you can see in these selections ("Mavericks and Outsiders: Positif Celebrates American Cinema"), we have David Holzman's Diary. We're difficult to pigeonhole -- it's the freedom of the magazine that makes it difficult to pigeonhole. But I think on the whole, when you look back on 55 years of issues and articles, I think it has an image -- an image due to the fact that several generations of critics live together at Positif; we don't have one generation which kicks out the previous one. Young people come to Positif when they have read the magazine for 5 or 10 years, and they decide they want to write for this particular magazine because it has this kind of spirit, this kind of freedom. So, therefore, there is a sort of unity, due to...in spite of the 70 year-old critics and the 25 year-old critics -- they belong to the same culture, though they are different, of course. The young people have their own ideas, a new vision of things, as do the older ones. It creates a rather unique experience. FILMMAKER: It's impartial. CIMENT: I don't know. We are pretty partial. We are partial on our own criteria. We are partial to our own individualism. We are not partial because of the trends. It's true that we are, perhaps, unfair with some films while praising other films. But the case of Kubrick is a very interesting case. Truffaut was established immediately as a great director. But, I think he is not as great a director as Kubrick. However, Kubrick was despised and neglected by a lot of critics even in America -- remember Sarris and Pauline Kael, how they reacted to 2001. So Positif was always a fan of Kubrick, as soon as Paths of Glory -- which was dismissed by Godard. So Kubrick or John Boorman -- I also wrote a book on Boorman -- they are very much what we try to be as critics: They have not decided to be this type of filmmaker, a filmmaker with a signature that you can immediately recognize. It was much more difficult for Kubrick to be accepted as an artist than for Truffaut or Jacques Demy. Everybody loved Demy immediately -- The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was immediately hailed. But The Shining or Full Metal Jacket or even till the end of his life -- Eyes Wide Shut was dismissed. So that's what we liked. We liked the freedom that he had. We try to, in our modest way, to behave the same, as critics. Labels: Web Exclusives

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 1/30/2009 06:23:00 PM

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

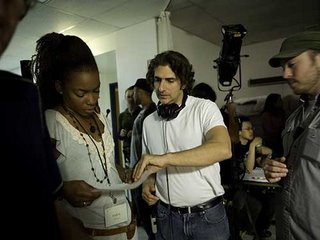

ROTTERDAM '09: THE HUNGRY GHOSTS

By Jason Guerrasio

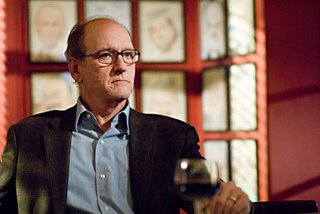

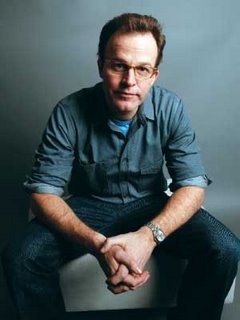

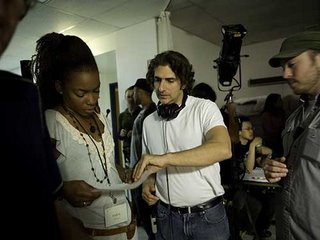

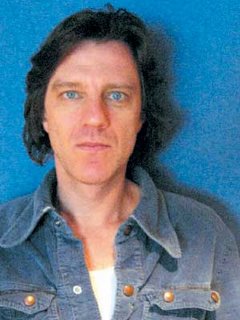

Opening this year’s Rotterdam International Film Festival is Michael Imperioli’s directorial debut, The Hungry Ghosts, a gripping look at five New Yorkers all struggling to satisfy their physical and spiritual needs while facing down their own – and society’s – flaws. Best known for his Emmy-winning portrayal of Christopher on The Sopranos, Imperioli has over the course of his 20-year career worked with such top directors as Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee. He’s also built a sub-career as a screenwriter, having penned numerous episodes of The Sopranos and Lee’s Summer of Sam, which originally Imperioli was going to direct. For The Hungry Ghosts, the title of which comes from a Buddhist metaphor for people futilely attempting to fulfill their insatiable appetites, he makes a film small in stature (shot on HD Cam and budgeted at $600,000) but large in ideas about life and the human condition. There’s also a strong ensemble of talent that Imperioli brought to the production from family, actors of Studio Dante (Imperioli and his wife’s Lower Manhattan theater group) and friends, particularly Steve Schirripa (best known as Bobby Bacala on The Sopranos), who gives a remarkable performance as a gambling, drug addicted overnight DJ and lousy father who attempts to reconnect with his son after a life-changing event. The Hungry Ghost is an impressive debut film that offers an uncompromising look at the complexities of life and the redemptive qualities we need to get through it. Imperioli talked to Filmmaker over the phone hours before catching a flight for Holland for the film’s premiere.  TOP OF PAGE: STEVE SCHIRRIPA AND EMORY COHEN IN THE HUNGRY GHOSTS. ABOVE: THE HUNGRY GHOSTS' WRITER-DIRECTOR MICHAEL IMPERIOLI. PHOTOS COURTESY OF CICALA FILMWORKS. TOP OF PAGE: STEVE SCHIRRIPA AND EMORY COHEN IN THE HUNGRY GHOSTS. ABOVE: THE HUNGRY GHOSTS' WRITER-DIRECTOR MICHAEL IMPERIOLI. PHOTOS COURTESY OF CICALA FILMWORKS. Have you always been interested in Eastern thinking? IMPERIOLI: It is something that has interested me for a long time. Their philosophy is something that I’ve been reading about for a number of years, and you start to examine your own life in terms of those ideas. The title didn’t come until the first draft was almost done, I wasn’t even totally sure that that was the direction it was going to go in, I was just writing from a sketch of the Frank and Nadia characters and it just kind of blossomed from there. FILMMAKER: In our Summer ’08 In Focus column you told Mary Glucksman that you’d been playing around with two characters for a couple of years. These were the characters? IMPERIOLI: Yeah. I had the Frank character as the host of a children’s TV show for another script that didn’t really go anywhere, and there was something about the character that I liked and something about Steve playing the character that I liked. I started writing the script using that character and then I had this idea of Nadia, played by Aunjanue Ellis, and the two of them together on a train. That was the initial seed of the script for The Hungry Ghosts. FILMMAKER: Had you always had Steve in mind to play the part? IMPERIOLI: Well, Steve and I are good friends. We met on The Sopranos but we became very, very close and one of the episodes that I wrote for The Sopranos was when his wife dies in a car accident. He did some stuff in that episode that really showed a lot more depth than he was allowed to show before. Then just knowing him as a person, knowing the depth of him as a person I thought it would be great to give him something really meaty like this. I knew he would be great but he really surpassed my hopes. His instincts were amazing. FILMMAKER: Are you interested in seeing how audiences will react to that character? He’s a jerk for most of the movie and at the end people may want to see him get what’s coming to him, but you didn’t go that route.

IMPERIOLI: Well, what I’m hoping is that people give him an opportunity to maybe now change, because where he ends up in the movie is very different than where he begins. Obviously the step in the right direction is that he hears his kid tried to kill himself, and he gets on a train to try to be with him. I’m not saying he’s going to become a guy who meditates all the time or starts to head towards Eastern spirituality, but at the end of the movie he is at a different place. What I would hope people get is that there is always hope no matter how ingrained you think your habits, addictions, ignorances and selfish behaviors are, that there is an opportunity to change. Hopefully it’s not at a point where it is too late. FILMMAKER: How did the multiple character structure come together? IMPERIOLI: I did a movie, I shot it about two years ago and it came out last year in Europe. It’s called The Lovebirds, and a guy named Bruno De Almeida, someone I’d worked with before, directed it. It was about six separate stories but there was something in the way that he told those stories that I really loved. We did a screening in New York right before I sat down to write The Hungry Ghosts, and I liked the way he told the story. I thought it could work for these characters.

FILMMAKER: How did you work with the actors, especially the ones from your Studio Dante theater?

IMPERIOLI: I think 18 or 19 of those actors in the film worked in the theater either in main stage productions or as acting students in our classes there. So I knew them and worked with most of them. Nick Sandow, Sharon [Angela] and Steve I’d worked with a lot before on many different things so that already gave me kind of a leg up. We did a pretty extensive rehearsal process — about two weeks every day we worked on the big scenes, and there were some [script] revisions that came out of that. It saved us a lot of time because when you’re shooting independently time is of the essence. They had already found their groove when they got to the set. FILMMAKER: I’ve read that a big influence on you has been John Cassavetes. IMPERIOLI: He’s been an influence on me, I really love his writing — I find him really underrated as a writer. A lot of people thought his movies were improvisations. I know people who worked with him — actually Zohra Lampert, who plays the Guru in my film, played Ben Gazzara’s wife in Opening Night. His stuff was scripted tightly, they rehearsed and maybe tweaked stuff in rehearsal but he was able to write in ways that he didn’t give everything away. He let the audience work and let them think. There’s something very organic about his writing that really inspires me. It definitely inspired me, but I don’t know if that’s evident when watching it. FILMMAKER: There is a lot of deep thinking in the film about the human condition. Was it therapeutic for you to get these thoughts on paper? IMPERIOLI: Yeah. I would say it was. And more so in actually filming it, not just the writing, but also the filming and working on it [with the actors].

FILMMAKER: I know you wrote Summer of Sam and had the opportunity to direct that, and you’ve written episodes of The Sopranos, so how did you directing not come sooner? IMPERIOLI: I wanted to direct Summer of Sam and Spike originally came on as an executive producer to help me direct it, but I never had the opportunity because we couldn’t raise the money to do it, which is probably a really good thing because I think it was beyond me at the time. We didn’t have the money so we kept rewriting it and then the scope of the movie kept getting bigger and it kind of encompassed more of the city and the riots and all of the stuff that’s going on. I kind of backed away because I really felt it was biting off more than I could chew. Then it kind of died for a while and Spike [came back to it]. And then I co-wrote a script for Peter Falk and he wanted to do it but we never got the money for that, so that’s just sitting in a drawer. That one I wanted to direct. I’ve been offered independents to direct over the years but I always felt that if I was going to direct something I wanted it to be something that I wrote. FILMMAKER: And they never offered you to direct episodes of The Sopranos? IMPERIOLI: No, for the same reasons. Directing television you really have to do what’s been laid out. There’s a template for that show and then you can add your own style, but I just didn’t have the chops to do that. That’s why I wanted to wait [until I had] my material and could make my own style on my own terms or mess up my own thing. FILMMAKER: Did you ever have to consider starring in The Hungry Ghosts to find the money you’d need to make it? IMPERIOLI: I got the money really, really easily. There were three investors, and the two major investors were my two biggest donors to my theater so they had been with us for five years. They really love what we do there and said if we were going to do a film to ask them. I wrote the script and asked them and they both wrote big checks. FILMMAKER: And you never thought of starring in it? IMPERIOLI: No. I didn’t want to direct my first movie and star in it. FILMMAKER: Where are you in your career now? Do you want to produce plays and direct films more than act?

IMPERIOLI: I want to do all of the above. I’m shooting [ABC’s] Life on Mars so I work a lot right now, but as soon as I’m done with that in March I’m going to start writing again. It’s really hard to write unless you have the discipline that everyday you’re going to do it and get into that rhythm. So the next free time I have I’m going to work on another script. Read our coverage of this year's Rotterdam Film Festival on the blog.Labels: Web Exclusives

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/21/2009 10:08:00 AM

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

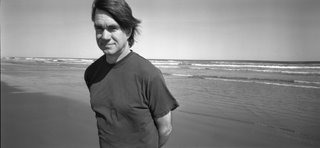

OF TIME AND THE CITY

By Scott Macaulay

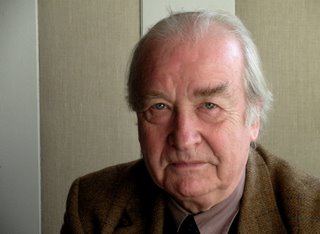

For Terrence Davies, his youth -- his early years in Liverpool, his relationship with his mother, and his feelings about being gay in that working-class town -- have always provided the raw material for his filmmaking. His celebrated “Terrence Davies Trilogy,” a collection of shorts, and later features like Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes summon up for the viewer an interior life with a rare combination of lyricism and heartache. These films cemented Davies’s international reputation, but after two more, non-autobiographical features ( The House of Mirth and The Neon Bible), he became less active, a development that had more to due with shifting trends in British film financing than his own creativity. But now, almost ten years after his last feature, Davies is premiering an unexpected success, his first documentary about – what else? – his early years in Liverpool. Of Time and the City is a lushly realized memory piece, a symphony of images, archival footage, narration and classical music that transforms grey old Liverpool into a digitally-realized reverie that is beautiful, sometimes acerbic, and always tinged with melancholy. Of Time and the City opens January 21 at New York’s Film Forum from Strand Releasing. I spoke with Davies this past fall at the Toronto Film Festival.  TOP OF PAGE: TERENCE DAVIES'S OF TIME AND THE CITY. PHOTO BY: BERNARD FALLON. ABOVE: OF TIME AND THE CITY'S DIRECTOR TERENCE DAVIES. PHOTO BY: SOLON PAPADOPOULOS. COURTESY OF STRAND RELEASING. TOP OF PAGE: TERENCE DAVIES'S OF TIME AND THE CITY. PHOTO BY: BERNARD FALLON. ABOVE: OF TIME AND THE CITY'S DIRECTOR TERENCE DAVIES. PHOTO BY: SOLON PAPADOPOULOS. COURTESY OF STRAND RELEASING.

FILMMAKER: I’ve read a number of interviews you’ve done for this film, and I’ve also read the reviews. They’re all fantastic. What’s it like talking so much about a film that is itself a revisiting of your childhood? TERENCE DAVIES: Well, I mean, it’s lovely because I’ve known what it’s like when people weren’t interested. After Neon Bible, no one was interested or wanted to talk to me. I’m as vain as anybody else, so it’s nice to have your ego massaged. I’m quite happy to do it because I never thought it would have this kind of reaction, I can assure you. It was made with the most modest of budgets, and the most modest of intentions. FILMMAKER: Tell me a little bit about how this specific project came to be. DAVIES: Well, it was by accident. Sol Papadopoulos, who was one of the producers, rang me up and said, “Do you remember me?” And I said, “Yes. You took some pictures of my mother about 20 years ago and they’re very beautiful. And I’ve still got them.” He said, “Well, I’m a producer now, and something called Digital Departures is coming to Liverpool, because it’s the European city of culture of this year. And they want to produce films for 250,000 pounds each, would you be interested?” And I said, “No. I don’t want to make any more fiction films about Liverpool. I’ve done that.” But then I said, “What might be interesting is to do a documentary about the Liverpool I grew up in, from 1945 onwards, and then contrast it with the new Liverpool, which is an alien city for me.” My template would be Humphrey Jennings’ [film] Listen to Britain, 1941, which is a great poem. It’s greater than a documentary -- it’s a poem. He was trying to capture the nature of being British when we were about to be invaded, and it’s glorious. I just wanted to capture what it was to be Liverpudlian – something much more modest. And he said, “Yes, we’d like to do that.” FILMMAKER: Was there any wrestling either on their part or your part with this notion of you, a fiction filmmaker, making a documentary?

DAVIES: No, because I’d written a sketch of what I wanted to do and we produced a six-minute trailer. I said, “Look, it is a personal essay. So if it’s not what you want, you better give the money to someone else, because it’s not going to be a straight documentary: this happened, that happened. I’m not interested in that.” FILMMAKER: Once you went through that process was this a hard film in any way to make?

DAVIES: Well, the hardest thing was actually what to leave out, because there was so much of it and some of it was ravishingly beautiful. We said, “Oh, I wish I could put that sequence in but I can’t.” It had to reach its natural length. You can’t force it. I’d written a sort of story, and, of course, that went out of the window very early because all this material brought back other memories of other things which had happened and which made me say, “Look, can you find footage from that or from this?” Or, “Can you find footage that’s in color?” All sorts of things. Memory is like smell. As soon as it’s pricked, it begins to work, and things that have lain dormant in you start to emerge. And memory, of course, is nonlinear. It’s completely cyclical and it’s completely disparate and elliptical. What you remember most intensely can be the tiniest things but they’re powerful for you because they have a whole emotional meaning beyond their surface meaning. And so it was quite hard to actually disregard some of that material. FILMMAKER: Well, that’s one of my questions. What was the ordering process for this movie? Not necessarily in the shaping, but in terms of finding the through lines and assembling all of these disparate things into a feature film. DAVIES: It was a mixture of finding material and then writing the through line. But you very rarely get to the through line fast. That is discovered while you put [the film] together. It’s like the through line of a script, of a fiction script. You find that eventually. I usually get it by the second draft, and then I do a polish. But here the script was being written daily. There were times when I couldn’t see the line, and that was very worrying. It’s not like sitting in your own flat with a piece of paper and a script and saying, “No, this doesn’t work. Why doesn’t it work?” You can walk around and shout at the walls, but you can’t do that in the cutting room. You just say, “Okay, it doesn’t feel right, does it?” And Liza [Ryan-Carter], who is a wonderful editor, says, “No.” But when something is right, you think, [ snaps] “Yeah.” Or you say, in a sequence, “No. If we take that out and reverse those shots and begin there, it will work.” And it does. Sometimes you get it that easily, and sometimes it takes three, four days. But I did say to her, “We’ve got to cut it like fiction.” When there was music, we’d cut it mute and then put the music on and see where the cuts fall. And then you’d sort of say, “Tweak it.” You’d say, “No, this cut here really has to come on the beat.” Or on that word. But others fell beautifully. The through line emerges subconsciously, and when it does, then [the film] begins to sing. But it takes a long time sometimes to get to that. FILMMAKER: Was one particular element – the music, the narration, the archival footage, or simply your memories – more central than the others to the way you organized the material? DAVIES: Well, I was writing the narration as I was cutting it. But we saw two films: one by Nick Broomfield, called Who Cares, and another called Morning in the Streets, the director of whom I’ve forgotten, ad I extracted things from them. I wanted to build up this idea of the street coming to life. Gradually the day begins. The children go to school. They play in the schoolyard. Their parents work hard. The school day ends. They come home. And again, I’ve no idea where it came from. I had heard on the BBC Radio 3, which is the classical music station in England, Angela Gheorghiu singing this Romanian folk song called “Watch and Pray.” As soon as I [heard it], I said, “That’s what we’ve got to have underneath it.” Don’t know where it came from. I have no idea. But that prompted all the reminiscing about Christmas, about going to war, Korea. (My eldest brother was in the army and had an accident and couldn’t go because he was injured very badly.) And then that led into the coronation -- I had to get the coronation and have a go at the monarchy because they’re such parasites. [ laughs] All that comes by searching – searching your own memory and looking at the material. FILMMAKER: How resonant was it for you when you first saw the archival footage? Because it’s not your archival footage -- it’s material that somebody else shot with an eye towards capturing history as opposed to personal moments. When you looked at this material did it take you back in time? Or did you have to work to allow your own memories to be triggered by it? DAVIES: Well, [the archival footage worked] in different ways, really. I mean, I remember vaguely the elevated railway, which was the first elevated electric railway in the world. It ran the whole length of the docks, which is between eight and 10 miles. I remembered it and I said, “You can find me some footage.” And the footage that we found was like outtakes from Metropolis -- they looked wonderful. But I was shocked at how awful the slums were, and I grew up in them! I never, never remembered them being as grim as they were. The sheer hard work just to keep them clean – just to keep your house clean, yourself clean, your children. That was a shock. It also brought memories back when the women used to go to the washhouse. My mother used to go on a Thursday. We only had one set of curtains, and they were washed every Thursday. And the house looked so bare without them. I hated Thursday, because I’d come home from school and there’d be no curtains on the windows and it looked so bleak. FILMMAKER: Have you seen Guy Maddin’s film My Winnipeg? DAVIES: No. I believe it’s very good, though.

FILMMAKER: Yeah, it’s very good. It’s about him cinematically remembering his hometown on the occasion of his move to Toronto. It’s a mixture of history and fiction, and a lot of the history feels like fiction. What was your take on historical truth versus the truth of memory in the film?

DAVIES: [ pause] Well, I think I would rely more on memory truth, because that’s more emotional, and that’s something that I’m more concerned with. That, too, in its own way, is real.

FILMMAKER: There’s a lot of talk in the American independent world right now about the need for new ways to make, distribute and even view films. What are your thoughts on where cinema is now? DAVIES: Well, I’m not sure. I haven’t worked since 2000, when I finished The House of Mirth, because The Neon Bible was before that. But the climate seems to be improving in England. The people at the U.K. Film Council now – like Lenny Crooks, especially – want to do films and they actually care about them. The previous regime did not do that. But what was wrong [previously] in England was the destruction of the production board of the BFI. It was an act of cultural vandalism to have actually got rid of it because it gave people their first chance to make a film, without any of this nonsense about, you know, “Well, it’s got a climax on page three,” or everyone’s got a back story, or all that nonsense – utter nonsense – that Robert McKee spouts. You had 25-year-olds telling you how to write a script. And when you said, “Well, how many have you written?” it all goes quiet. “Well, how many have you written?” “None.” “Oh, I see. So, you’ve written no scripts and you’re telling me how to write them and I’ve been writing them for 30 years? I think that’s a bit arrogant, don’t you?” And you shut the door. I hope, with things like Hunger – which I’ve not seen, but it was a very courageous film to be funded by Channel 4 – the climate has changed. There’s hope there. I’m glad that my film got funded, and I hope that provides some hope for other people. But once you get into the position that Britain is in – being a client nation of America, with all the indignity that goes with that – you’re in trouble. Because now, culturally, we look to America for validation when we should be looking either to ourselves or to Europe. Our future does not lie with America, and neither does our culture. Now, in England, if you want to celebrate anything about our culture, you’re dismissed as elitist, or middle class. It’s almost fascist now. It’s exactly like it was after the civil war, when you had to be politically and religiously correct. Hopefully that will go. It’s far too early, but I am cautiously optimistic. FILMMAKER: What about new ways of viewing films, whether that be through the internet on your computer, or on a handheld device? DAVIES: I’m a technophobe. I don’t understand all this new technology. I just simply don’t understand it. If we’ve got to make things on digital, I will do it, because I enjoyed it. I think digital will probably replace film, because it’s quicker and all the rest of it. But all that downloading things, I have no idea what it is. At the end of the day, if you’re going to make a film, in whatever format, the only real way to see it is on a large screen in a darkened room with other people. There’s no other experience like it. Watching it on DVD or an iPod is not the same. Watching it on television is not the same. It’s not like sitting in a full theater with a huge screen. Everyone responds to it collectively, yet everyone feels that the secret is only being told to them. Nothing replaces that. Labels: Web Exclusives

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/20/2009 10:00:00 AM

Monday, January 19, 2009

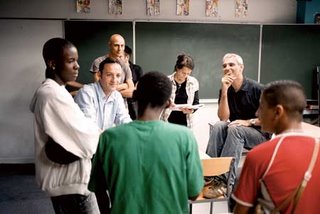

DRAWING FROM MEMORY

By Nick Dawson

Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Nick Dawson interviewed Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Nick Dawson interviewed Waltz With Bashir writer-director Ari Folman for our Fall '08 issue. Waltz With Bashir is nominated for Best Foreign Film.It’s been said that the job of the filmmaker is to put on screen things that have never been seen before. And while cinema is essentially an infant art form, these days there are still relatively few films that move into genuinely new territory. Waltz with Bashir, which opened this year’s Cannes Film Festival, is one of those films. In this unique documentary, Israeli director Ari Folman attempts to reconstruct the missing memories from his time as a soldier in the 1982 Lebanon War. His main goal is to discover where he was during the massacre at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp, a revenge killing of hundereds of Palestinian civilians by Phalangists in response to the murder of newly appointed Lebanese president Bashir Gemayel. To piece together his past, Folman visits old friends and interviews soldiers he fought alongside, and this journey of discovery is as compelling a narrative as any piece of fiction. While the unflinching, personal detective story aspect of Waltz with Bashir already makes it unusual, what makes it even more so is that Folman’s documentary is animated. Though on paper this seems like an impossible collision of genres, Folman uses the freedoms that animation gives him to take the film to places another documentary could not go. What’s more, Folman plays with our preconceptions of cartoons always belonging to the realm of narrative filmmaking, and in the process asks exactly where the line between documentary and fiction lies. And while Yoni Goodman’s vivid animation, hand-drawn and in a variety of styles, looks stunning, it always complements rather than distracts from Folman’s compelling and ultimately moving tale. Sony Pictures will release Waltz with Bashir this December.  TOP OF PAGE: A SCENE FROM WALTZ WITH BASHIR. PHOTO BY: ARI FOLMAN AND DAVID POLONSKY. ABOVE: WALTZ WITH BASHIR WRITER-DIRECTOR ARI FOLMAN. PHOTO BY HENNY GARFUNKEL/RETNA LTD. TOP OF PAGE: A SCENE FROM WALTZ WITH BASHIR. PHOTO BY: ARI FOLMAN AND DAVID POLONSKY. ABOVE: WALTZ WITH BASHIR WRITER-DIRECTOR ARI FOLMAN. PHOTO BY HENNY GARFUNKEL/RETNA LTD. It was a very conscious decision. You can imagine that I got a lot of criticism — even for the screenplay — that I’m not there in the first frame and that it might confuse the audience about who the protagonist is in the film. But, I mean, how narrow-minded can we get? It’s true. I think we do usually assume that the first character whose perspective we see from will be the protagonist. You’re right. It was a deliberate decision and I insisted on it. I saw this other film here [at the Toronto International Film Festival] called Hunger. The main character appears after 14 minutes, and the film is amazing. You don’t need to be hooked on conventions. Did this film start out as a personal attempt to recover your past? Well, I’ll tell you how it started and you decide. Five years ago, I turned 40. In Israel, I served a few years in the army and between two weeks and a month [of every year] you’re a reservist. I was a screenwriter in the reserves doing shorts and commercials [on topics] like how to defend yourself in a chemical attack, and I got really tired of it although I hardly did anything. I asked for a release a few years earlier than usual and they said, “You know what, we can give you the release but there is this experiment the army is working on. You will have to see our therapist for a few sessions and tell him everything you went through during your service.” So I went to 10 meetings, and when they ended I realized that it was the first time I ever told my story to anyone — even myself. The content of the story was not that amazing, but the fact that I never dealt with it for more than 20 years was amazing, for me. So I went to my inner circle of friends and family and I tried to see if people felt the same, and they did. Then I thought, “Okay, there’s something going on here.” At the time, I was working on this documentary series called The Material That Love Is Made Of and it was the first try I made with animated documentary. I started imagining this journey because I had these black holes in my memory when I was at those sessions with the therapist. I started imagining this animated journey where I go to pick up all those pieces that I’m missing. So this is how it all started. Did you do historical research about the events depicted before going into the personal aspects of this journey? I advertised on the Internet that I was looking for stories from the first Lebanon War. I got a response from something like 100 men, and we heard all those stories, which were quite extreme. Afterward I wrote the screenplay. Most of the research, of course, is out [of the movie] because we had to keep a very narrow storyline. Then we shot everything on a sound studio, because I thought that the human ear is totally non-tolerant to location [sound] in terms of animation. We cut it as a video documentary film and then we made storyboards out of the video because it’s not a rotoscope film. We moved the storyboard really basically. We picked something like 3,000 key frames and then we would move them. So the journey that you take in the film is one that you took yourself in real life prior to filming? Yes. I met all those people, and then at the studio we tried to dramatize everything, like if I was interviewing someone in a car we would sit one beside each other with plastic wheels and pretend it was a car. And when you were shooting it in the studio, you got the real people you had interviewed to recreate their conversations with you? I did, but we had two actors in the film too because the guy from Holland had cold feet a few days before shooting. He didn’t mind [being in] the story so we took his monologue and we gave it to an actor and we invented a new face. It’s one of the things you can do when you have the freedom of animation. Basically, we were having the same discussion as he had twice before, first with the researcher and the second time with me. What was it like to recreate these conversations on a sound stage, acting almost as if they were fiction? First, it depends who you are. For example, the journalist [Ron Ben-Yishai] has told his story probably at least a thousand times — he wrote a book about it and you can see in the way that he’s talking. But the swimmer, for example — it was the first time he had told his story after so many years. He had so much to get out of his thoughts and the third time was better than the first. It’s something really personal. With someone like Frenkel — the karate guy, the dancer — the first time was the best by far. When we met at my studio after so many years, he couldn’t do it again. It was not as good. So, one is for the better, one is for the worse… I still don’t know if I have the best version… but, you know, that is the price you sometimes pay when you make a film like this. Why did you specifically conceive this as an animated documentary? It seems that almost anybody else would not have tackled the story in this way. Well, frankly, it isn’t important to me. I’m kind of tired of film formats and if I would have declared this film five years ago as a fiction film, I would have raised the money much easier and I’d be more secure and I would have completed it a year ago, at least. I don’t know why I declared it an animated documentary, but I did. I mean, who decides? Is there a committee who decides when a specific film starts off being a documentary and turns into fiction, or the other way around? I wouldn’t know. I just don’t know what to say, and I don’t care. I mean, this is the film, okay? You’re the journalist — you decide. If you decide that for you it’s a fiction film, I’m happy for you. If, for you, it is in the structure of documentary or what you define as documentary, I’ll go with you as well. I think it’s great that you can choose. Why should I choose? When I was scribbling notes on the film, I called it a “recalled documentary.” I mean, would it feel more convenient for you if it were a fiction film based on true stories? I don’t think so. I don’t feel there’s one easy way to categorize this film, and I think that’s a real strength. This was obviously the way that you felt you needed to handle the material, so the label that other people put on it is not important to you. Totally. Because of the ambiguous genre the film sits in, was it difficult to pitch? I was at Hot Docs three-and-a-half years ago; I had a three-minute scene and I pitched [the film]. There were 40 coordinators from documentary funds and [television] stations there. You had to declare that you had 40 percent of your budget — of course, I didn’t even have 5 percent, so I had to lie but I was selected anyhow. Thirty-eight out of the 40 took their microphones and said, “Why animation? It’s a documentary, we’re at a documentary film festival. Why can’t you film the real people?” It is weird for me to explain, “why animation,” even now. It’s the most frequently asked question since Cannes, and it’s still the one question I can’t understand. I mean, of course it’s an animation ‑ how else could it have been done? It’s absurd to me. When you realized the film should be animated, did you have a clear picture of how it should look, and the particular style of animation? I had a clear vision, but it was more than a clear vision: I was obsessed with a few things. First of all, that the audience would still be emotionally attached to the characters, and that meant for me that we would draw them as realistic as the illustrators could. Meaning, we should put as much detail as we can: more contours and shapes; and, of course, the more detail you have in a face or in a body, the more complicated it is to animate it, to move it, especially in cut-out animation, which is the main thing. And then we had the dream sequences, which are more freehand, open in terms of color and shape, and then we had the last part of the film, which is more of a hardcore documentary. When you go to the massacre, it is monochrome and a little more depressing. You know, in this kind of animation, the style dictates the animation and not the other way around. As the animation process took so long and you were working on Israeli TV shows at the same time, how involved were you in the day-to-day postproduction process? Believe me, I was working on the film. I was involved in every frame. It is about giving the film cinematic taste, trying every little thing that will work as a feature film. Because it takes time, we were screening the materials every two days and reworking them, every shot, every single angle, every aspect of the film. A frame here, a frame there. But Yoni’s main role was that he created the technique of this specific animation, which is an incredible thing. And what is that technique? This is his invention, a combination of cut-out animation, flash-based [animation], classic Disney frame-by-frame animation and 3-D animation. And then he had to instruct the team because no one was qualified like him to do what he had invented. We only had eight animators. And when we needed two more, we couldn’t find them. The film has a great score by Max Richter, and I was wondering how early on you had a clear sense of what the music and the sound design of the film would be? I started to work with the guy on the video-board stage already. First I went to Edinburgh [where Richter used to live]. We met and I screened the video board to him so he could see the color of the thing. I told him what I believed should be in every scene, and gave him guide [tracks]. I put in guides in every scene — I always do that. I put in music for my mind, but I don’t understand how [composers] can compete with the guides that film directors give them. There was Brian Eno stuff in there, and Sigur Rós — good things to match. High challenge. But he did it. The guy is absolutely brilliant. What was the personal impact of making this film and succeeding in uncovering that lost portion of your past? Was it cathartic? It was kind of a therapeutic journey, but any filmmaking is. I would say that five years ago if I had looked at a photo of myself from when I was 19, I would have recognized the guy but felt totally disconnected. And now I live in peace with everything. This is the major change I went through. The end of the film has a huge impact as we move from animation to news footage. Was the feeling of that shift similar to what you felt when you regained your memory of the massacre? Yes, it is as if you regain your memory and in a symbolic way as if you regain the real footage. In the end, we were not on the beach when the massacre took place, we were outside the camps. Basically, the ending was done just to prevent the situation where anyone anywhere would walk out of the theater and think that it was a really cool animated film with really cool drawings. I wanted to let people know that it really happened. Real people, they died. Thousands of them. On the other hand, if the film is like this bad acid trip like war is, in the end you wake up and this is what you see. So it works both ways. Labels: Web Exclusives

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/19/2009 04:00:00 PM

GOTHAMS TRIBUTE: PENÉLOPE CRUZ

By Jason Guerrasio

Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Jason Guerrasio interviewed Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Jason Guerrasio interviewed Vicky Cristina Barcelona star Penélope Cruz for our Gotham Independent Film Awards special section in the Fall '08 issue. Vicky Cristina Barcelona is nominated for Best Actress (Penélope Cruz).Talking over the phone from London where she’s rehearsing her role in Rob Marshall’s film adaptation of the Tony Award-winning musical, Nine, Penélope Cruz sounds humbled when congratulated for being named one of this year’s Gotham Award Tributes, but she admits there hasn’t been much time to think about the honor. Before filming Nine, Cruz wrapped production on her next project with Pedro Almodóvar, Los Abrazos rotos, a modern-day noir where she says she plays “a very different character from anything that I have done for Pedro before.” This comes off the two distinctly different roles she performed on screens this year — Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona and Isabel Coixet’s Elegy — where she has received some of the best reviews of her career. In Vicky Cristina, Cruz plays Maria Elena, a fiery Spaniard who is the ex-wife of Javier Bardem’s Juan Antonio, a playboy painter who woos two American girls to Barcelona during their summer vacation. But when Maria Elena reenters Juan Antonio’s life she takes over the film: Her heated exchanges with Bardem, spoken in her native tongue, are one of the film’s highlights. In Elegy, based on the Philip Roth novel The Human Stain, Cruz is more subdued. The obsession of an aging bachelor played by Ben Kingsley, her character, Consuela, is more than a mere sex object. In full control of the situation, Consuela wants to take the relationship further than the occasional romp, and when she doesn’t get it she breaks it off with a voice message that is itself a heartrending minimonologue. In her mid-thirties, Cruz has been nominated for an Oscar and is an international star, but as Filmmaker learns, both of her performances this year are examples of her continued drive to challenge herself by playing women who fascinate her. Most times Woody Allen has an actor already in mind when he casts his films. Is that what happened with you for Vicky Christina Barcelona? No. I think my agent found out that he was going to shoot in Spain so he called and got a meeting. I had never met Woody before and the meeting was 40 seconds long. [ laughs] He said he was writing but the script wasn’t finished and that he would let me know because he thought there was a character that could be right for me. Then a month later they called me and said Woody wanted me to do the movie. It’s been a great experience. I would love to work with him again because he shoots very fast — I did my whole character in three-and-a-half weeks but I wanted more time with him. How would you compare his style to Pedro Almodóvar’s? I think the only thing they have in common is they are both geniuses with an amazing sense of humor. Most of the time their characters can laugh about pain and human confusion in a way that almost makes you feel guilty when you are working in those characters. You suffer as part of the audience sometimes. I love that feeling because they challenge you. And their systems could not be more different; it’s like day and night. Pedro rehearses for months and months and Woody doesn’t rehearse. But I didn’t miss rehearsal time working with Woody because he gave me a script many months before so that is his way to make sure that you have the time to feel ready [for the role]. It’s good to jump into that adventure. How did Elegy come about? I was attached to the project for about five years with producers Tom Rosenberg and Gary Lucchesi. We finally put it together when Ben Kingsley and Isabel Coixet came on. I think they are the perfect people to do that movie; I can’t imagine another actor doing that character than Ben and I think Isabel is the perfect director to bring Philip Roth’s world to a movie because there’s just something that she has, her eye and her sensibility. Many have called this your best English language-speaking performance to date. Is it still a challenge for you to do English-speaking roles? It will always be a little difficult because it’s my third language. I learned English when I was 18 and I knew French before so it’s always hardest to learn it that late. But I feel much more comfortable now because I have lived in New York and L.A. and had to use it in real life. When I started my career in America I really didn’t speak it, I only knew my dialogue so I’ve been working very hard all these years, and I’m still working on it. I want to keep working on the accent. But I feel more freedom and I can understand what’s going on because in the beginning I couldn’t. You do a healthy mix of Hollywood movies, indies and Spanish-language films; is there a preference? I think every movie is a new adventure, a new goal, a new challenge and I see it like that, one at a time. My home is in Spain, sometimes I live in L.A. and I don’t want to stop working in Europe. If good, interesting projects keep coming from America I’m so happy to be part of them too. I don’t make a plan of every year going to work more there or here, it’s just more of what comes up. Now I’m making an American movie and I couldn’t be happier, but I don’t know, maybe later I’ll do three Spanish movies in a row. What was it about the characters you play in Vicky Cristina and Elegy that interested you? Those characters are very different, very complex women, women that I would like to know and explore and understand. When I read about them I felt fascinated by them. That was what made me want to do them, and I’m just happy that I’m receiving these offers of characters like this. When I say this I don’t want to make it sound less about the projects that I’ve done in the past, because I don’t measure the success of a project by how well they do at the box office or how good the reviews are, I measure it from how much I learned when I was making those movies. And what does a role need to spark your fascination? The ones that are going to make you feel like this is the first time you’re on a movie set, that make you feel new. There’s an insecurity that comes from acting that is natural because you can never control everything. That is a beautiful insecurity, and you have to feel like that to enjoy making a movie. I’m interested in the characters that are going to make me feel frightened. The farther they are from you the farther they are from each other, like these two movies where they are so different. But I think we all look for that with this job. It’s just great when you get the opportunity, and right now I feel very grateful with the opportunities that I’m being given. I cannot complain right now to tell you the truth. Labels: Web Exclusives

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/19/2009 03:50:00 PM

SMUGLER'S BLUES

By Scott Macaulay

Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Scott Macaulay interviewed Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Scott Macaulay interviewed Frozen River writer-director Courtney Hunt for our Summer '08 issue. The film's lead, Melissa Leo, was also interviewed in a sidebar to the piece by Jason Guerrasio. Frozen River is nominated for Best Actress (Melissa Leo) and Best Screenplay (Courtney Hunt).At Sundance this past year, two films in the Dramatic Competition especially stood out: Lance Hammer’s Ballast and Courtney Hunt’s Frozen River. It’s easy to mention the films in the same breath, because both are examples of regional American independent cinema attuned to the economic realities of life in this country today. They each feature characters mainstream Hollywood films rarely notice: single parents hovering just at or most often below the poverty line. People struggling to contain a justified depression in order to help a neighbor or keep food on their family’s plates. But beyond these similarities, these two excellent films could not be more different. Ballast is loosely structured and its story points are small and indicative of the randomness of life. A subplot in which an armed child is threatened by local teen thugs is allowed to gently dissipate while the film’s emotional climax occurs when one character learns to use a credit card machine. Clearly influenced by the Dardenne Brothers, Ballast finds truth in the people and the moments movies often ignore. Frozen River also begins by introducing us to the kind of working class character Hollywood has largely forsaken, but rather than remain intimate in its ambitions, the film steadily becomes a tersely executed, plot-driven thriller; it’s got the kind of classic Hollywood storytelling that even the studios rarely pull off anymore. And in addition to its indelible portrait of a blue-collar mom, the film makes complicated and resonant points about this country’s current debate around immigration and the nature of the American character. Set in upstate New York near the border of Canada, Frozen River introduces us to Ray (Melissa Leo), a single mother who works at a local retailer and tries to save enough of her minimum wage to feed her young son and daughter. When her economic situation becomes dire — and she’s about to lose the sizable down payment she’s put down on a new prefab home — Ray joins a Mohawk Indian woman, Lila (Misty Upham), in her illegal immigrant smuggling operation, ferrying in the trunk of her car poor Chinese workers over the icy border to Canada. The smuggling trips go well for a short while but soon, of course, things spin out of control…. Frozen River, which will be released by Sony Classics this summer, is the winner of Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize.  TOP OF PAGE: MISTY UPHAM (LEFT) AND MELISSA LEO IN FROZEN RIVER. PHOTO BY: JORY SUTTON. ABOVE: FROZEN RIVER WRITER-DIRECTOR COURTNEY HUNT. PHOTO BY HENNY GARFUNKEL/RETNA LTD. TOP OF PAGE: MISTY UPHAM (LEFT) AND MELISSA LEO IN FROZEN RIVER. PHOTO BY: JORY SUTTON. ABOVE: FROZEN RIVER WRITER-DIRECTOR COURTNEY HUNT. PHOTO BY HENNY GARFUNKEL/RETNA LTD. It’s funny, because Tarantino said that too. I never thought of it that way. I just think if a story is good enough to compel people to watch it, then it’s a good movie. And so when I’m writing, I work on structuring things so that you have got to keep turning the page, or you’ve got to keep sitting there and seeing what happens. You have to get invested. But I didn’t think of it as a thriller. You have all these thriller elements. There’s danger throughout, and you have a car chase. And the great thing about the car chase is that because it’s on ice, it’s a slow speed car chase, which is a fantastic twist on the way car chases are usually handled. Well, I hate car chases in movies deeply, and I wouldn’t have been any part of one if it hadn’t grown right out of that story. But that clumsiness of how they aren’t moving very fast made it okay. When did you begin the first incarnation of Frozen River? I had an idea when I was graduating from Columbia Film School — I wanted to do a story where women were really active, where they were doing stuff. Not relationship stuff, just stuff in the world. Acting. My husband is from extreme North Country, which is north of Albany. I learned from him about this Indian tribe, the Mohawks, and that this [smuggling] went on. I met some women smugglers who were at that time smuggling cigarettes across the river. It was simply a business to them. They told me about some of their adventures, and I thought, why would [these women] do this? I talked to a few [producers and executives] about it right after Columbia. I was like, “I’ve got this smuggling story.” And they were like, “What are they smuggling?” “Cigarettes.” And they were so not into it. Then I wrote this other script but it didn’t really work. Remember how after 9/11 there was this whole year of [questioning whether] art can happen anymore. Well, I learned that [the Mohawk women] were then actually smuggling immigrants, and I thought, “Hmm, this really is relevant.” So those characters, especially Ray, who I tried to kill off and to put in a drawer, just kind of came back up. I was writing something one day and I just started writing her point of view, and that became the short [film of Frozen River]. After [the short] went to the New York Film Festival, I thought, “Okay, this thing has some legs, let’s fill it out.” The short was a success on the festival circuit? Well, it made a big splash, but it was kind of an iffy short in my opinion. I mean, it played by most of the rules. How helpful was the short in fund-raising for your feature? Being in the New York Film Festival made people pay attention, but my husband and I still couldn’t get anywhere with [the feature script]. I shopped it all over the place. Melissa [Leo] and Misty [Upham] were on board from the beginning, and any big place we went to immediately wanted us to get bigger names, but that was just not what this story needed. I’d say, “You help me find somebody who is better and I’ll lose them, but there’s nobody better than these two.” Finally my husband said, “How hard can it be to write a prospectus?” So we did and took it to these investors, people we knew or knew of, and we found four people. And obviously [because of the short] they knew that I knew what to do behind the camera, could tell a story and that the characters were engaging. These were not film investors? No. And then in terms of deciding what scale to make the film, I don’t know the budget… Teeny. But there’s probably very different ranges it could have been made for depending on who you were making it with. Exactly. So how much of what you said you were going to do did you actually do? In other words, how much did your production match the prospectus? Pretty much exactly what we said we were going to do we did. We got it in the can pretty much exactly [on budget], and then there have been more post expenses. They’re a drag. They’re still going on. But yeah, we did it for what we said we could do it for, which was impossible, but we could get away with it with this story and setting. It’s gritty — it didn’t have to be beautiful — and the weather was forgiven when it wouldn’t cooperate. We shot in HD, which was a savings, and we had some people who were not as experienced but they worked very, very hard. We went to a place that wasn’t at all film savvy and [the locals] were into it. It was a story about their region and everybody knew this kind of stuff goes on, so everyone had a story of their own to tell. It was fun — the whole town was involved, and that’s what you want. It was great. I mean, it was miserable, but it was great. How did you find your crew? They all came from a little place called Brooklyn. [laughs] My d.p. lives in Brooklyn, one of my producers is in Brooklyn. It was a New York crew, all the grips and gaffers. They were very good, and very young. For some of them it was just their fourth or fifth film. How did you find Melissa Leo? I met her at this little film festival in Chatham, New York, called FilmColumbia. [Focus Features president] James Schamus will often show whatever he’s got upcoming, and he brought 21 Grams. And she came — she’s really good in that movie. I met her at the party afterwards. I’m not much of a schmoozer, but there she was with her big hair and I sort of cornered her. She was really nice, and then I sent her a short and another script. Then my husband said, “Courtney, what about the smuggling thing?” I was like, “Oh my God, you’re right!” So I sent her that short and that’s kind of how this happened. Earlier you said you wanted to make a movie where women are active and out in the world. Is that how you’d pitch the movie to people, by referencing that desire? You hear these things at film school about how women’s movies tend to be talky, sort of like Fried Green Tomatoes. I so resented that. I mean, I was raised by a single mother, and she was not talking — she was doing stuff all the time just to get by, but somehow that stuff is not considered “action” or interesting. So to hear it called a thriller now is really gratifying because it just means that something happens in it that grips you which life often does for men and women. Your screenplay is rock hard. There’s no flab, the beats are precise and there’s purposeful foreshadowing. You know when they drive past that police car two times and aren’t caught that they’re not going to sail past the third time. All the secondary characters have their very specific wants and needs. So what was your development process like? How did you arrive at such a classically structured screenplay? I went through three drafts. There were subplots and other things. I had to decide whether or not to see the husband. That was a big issue. In terms of the “threes,” rather than that being an invention, I think that’s a natural arc. Did I sit down and think, “Oh, they’ve got to go past this trooper three times?” No, but it naturally worked within the context of the story. You know what I did? I wrote everything I needed to write and then I took everything out. I just stripped the script down. I don’t like dialogue-y movies, and I didn’t think that witty, clever dialogue would really be believable. But I’m not sure how to really answer the question. You just did. All I was really saying is that the movie seems precisely plotted and structured. One reason it seems that way is because we didn’t have any fucking money. And so it was like, get the story told and don’t waste time. There’s a lot of plot in a tiny movie. I didn’t have any throwaway scenes. You’ve got to understand what the hell is going on at the border, what the hell is going on with her husband, and who this other woman, the little kid and these random Mohawk characters floating around are. I didn’t have the luxury of going off in any kind of direction except what was happening with [Ray] and where she was going. And she’s kind of that way too, the character. She’s trying to get it done, and I was just trying to get it done. And how about the ending? So much independent film explores concepts of the family. Breaking it apart and putting it back together again. I found your ending completely unexpected and realistic, while still being deeply satisfying on an emotional level. How long did it take you to find it — was that the ending from the beginning? Or was that the ending you found? I found that ending. I didn’t know [what the ending would be] for a long time so I just left it at bay. And when I got to that final hard character read for [Ray], that last one, it just bubbled right up. It sounds so ridiculous, but I really do listen to the characters’ voices, and the better I listen, the more they tell me. If I’m trying to control them, if I’m projecting myself onto them, you can tell because the writing stinks. But when I took this totally groovy approach and said, “Okay, what does Ray have to tell me today…?” If you really get in the habit as a writer of listening to what your characters say and honoring it even if it seems weird, then often the ending will grow right out of it. [The ending of Frozen River] was almost a surprise to me, but it was sort of right there [in the logic of the story]. I did just let it literally bubble up. How late in the process was this? Late! When I got closer to shooting, I felt like the pressure was on. I had taken people’s money, I promised to do the best I could to pay it back, and that meant telling the story economically and effectively in the least amount of scenes possible. I felt I had one chance to tell the truth of this character and I’d better not screw it up. So I really devoted myself in those last few tinkering rewrites to just getting in there, and if it felt like a false note, out. I let scenes fall out. There was a huge opening scene that never got shot because it was too expensive. What was that scene? It was the whole backstory of Lila and when her husband goes through the ice. She’s pregnant and he’s gone in the ice and she’s trying to pull him out. It was big Hollywood. People would read it and they would just burst out laughing, like, “You’re insane!” Some people said to me, “Cut it off, you don’t need it. Nobody cares.” And that’s why you have very little of her backstory. How much was Melissa involved in the creation of her character aside from simply portraying her? She is really exacting in a great way. She holds your feet to the fire on every motivation, every choice. If she doesn’t believe it, she’ll tell you. Luckily on this one she and I were on the same page. The thing about Melissa is, she only challenges you when she’s right. And she’s pretty much always right. She picks her battles and she picks them to win. If she wasn’t so right all the time, she’d be a pain, but she’s great. And what about Misty? Misty is a different kind of actress. She’s a very gifted actress, a “one-take” actress. She just nails it. It was really annoying to Melissa. They’re a total odd couple. There’s such a stoic thing about [the character of] Lila, but Misty is not really like that at all. She’s really funny, and she’s a baby — she’s like 22. She has that great quality that makes you almost think she’s a non-actress. She totally plays her character. Everyone assumes that she’s this little Native American girl we pulled in. But no, she’s actually a well-trained, very gifted actress. Shows that you can cast off the Internet. You cast her off the Internet? I went to a Native American actor Web site and I looked at all the pictures, and I was like, “Hmm, does anybody actually look like a Native American instead of Shania Twain or something?” And she did. She had a gorgeous look. She looks [from the] Mohawk tribe. So I just called her up and she came, got off the plane and started acting [in the short] the next day. There was no audition. Were you inspired by any other films while making Frozen River? Oh, yeah. Everyone is talking about the ’70s movies now. I was brought up on them, my mom and I would scrape together money to go to the movies. She was really great at taking me to every thing. I was not that popular a teenager so I spent a good deal of time in the movie theater. I saw every Bergman film. I saw Lina Wertmüller, I saw Arthur Penn, Bonnie and Clyde. I love Paul Schrader. But in terms of this movie, I looked at Badlands. And of course I love The Searchers. [ Frozen River] is set in a sort of border area, and I thought of it as a frontier, as, a little bit, the Wild West. I have a very traditional, Southern dad, and he really likes John Wayne. I told Melissa to watch John Wayne in Rio Grande, to watch how he does absolutely nothing but gives up everything. He’ll do nothing and you’ll be in tears. Melissa tends to be much more expressive, so I was like, “You’re John Wayne — give us less.” So, yes, John Ford and John Wayne were very inspirational. In this post 9/11 world, immigration and the border security are big issues. When you listen to the anti-immigration folk, they seem not just concerned with national security but with protecting a certain kind of “American identity” from outside influence. Your ending takes these issues head-on, but, at the same time, it feels subtle and nuanced and originating from character. How conscious were you about your film’s potential political message? When [I wrote the ending] I had to accept that “this is what you have and this is what the characters told you.” So was I going to stick with them or get in there [and change it]? I didn’t want to touch it, and then I thought, “Who is this going to offend?” And I didn’t even care. I don’t think we’re clear about immigration as a nation. The discussion is going on, it’s developing and this is part of the discussion. Is it dangerous to have people streaming over the border? Yes it is. But on the other hand, the large majority of those people coming in are coming with a good intent. So it’s very much your typical American debate. I didn’t set out to say anything about immigration, I’m just calling it like those characters see it. There is no overall agenda. I took myself out of it, because I’m much more a screamer, but they aren’t. Was shooting HD your choice from the beginning? I felt okay about it because I knew I probably couldn’t afford film. What I was shooting is not so sumptuous that beautiful scenery was being lost. The camera was good — it only clammed up once — and we played fast and loose with lighting a lot. We weren’t so constrained as we would have been on film. And a lot of it’s at night, so that’s really great for HD. We had no dailies… But you were shooting on tape, couldn’t you have just watched what you shot? We could have, but we didn’t want to because that was our original. So we’d only watch the tiniest bit, and we only got to see dailies the second week of the four-week shoot. By then you were making dubs? Right. We finally started getting them. We just didn’t have the money to kind of make that happen [in the beginning]. Someday I want to shoot a movie where I get to see the dailies, although there was something great about not seeing them. You are out there, and you’d better get it right. With HD the exteriors can sometimes be harsh. And they are, but for this film, that’s okay. HD is so bright, it seems like there’s white in everything, even the blacks. When I saw the film out for the first time, I got all upset because it was moodier, and it made it sadder. It’s a hard movie to watch. Most people don’t live in that world, and asking someone to sit there for 97 minutes and live in a trailer is tough. The brightness of HD had kind of lightened it a little bit. So when I first saw [the transfer], I thought, “Something’s wrong, it’s way too dark, they’ve messed it up.” And then I was like, “No, that’s just what film looks like [ laughs].” And as soon as I made that transition I was okay. It’s so rich, and black is black again, and it’s great. Were there any surprises when you put the story together? I had a great editor, Kate Williams. We had no money for postproduction. I had pieces of the movie and the cassettes in my purse and just dumped it in her lap. We went to the Edit Center and that was unique because she got to see everything before we actually committed to each other. And I got to see that she was really good. She was an instructor at the Edit Center? Yes. So the students did your first cut at the Edit Center. How was that process? It’s interesting because you have people who are going to learn how to edit a movie, and they’re going to do it in six weeks. I spent five years on this project, my guts are all over the ring, and they want to play, as, of course, they should. But this was my heart and soul, and I was like, “You’re not dropping any scenes from my movie!” I think it was a good experience for them to see what really happens between a director and an editor, how that dynamic gets set up. So what happened after you made that rough cut at the Edit Center? Kate came up to the country and brought her family. We set up the Final Cut Pro system in the garage, our kids played together, and we cut all of July and August. My friends have a little guesthouse, so she and [her husband] Matthew lived there with her boys. It sounds kind of idyllic. It was pretty cool. Kate is incredibly dedicated. When she goes into [an edit], she goes all the way in and she does not come out until it is done. If the story is good and your actors are good, there’s a lot to work with and editing is really fun. I mean, there were a few things we had to finesse, but the basic dramatic structure was there to lay the film on. And she saw that, and so we just did it. It doesn’t really come through in the script as much as it actually comes through in the acting. The script is a little bit bare bones. I think when she read it at first she was kind of like, “Interesting, but what is this?” But when she saw the footage she was like, “Oh!” Because of the performances? I think when you can see that river and how dangerous it is, it’s just much more powerful than it could ever have been written.  MELISSA LEO IN FROZEN RIVER. PHOTO BY JORY SUTTON. MELISSA LEO IN FROZEN RIVER. PHOTO BY JORY SUTTON.A veteran character actor with more than 20 years of experience on the stage, television and big screen, Melissa Leo isn’t the type to get giddy over recognition, though she admits the reception she’s gotten for her performance as Ray Eddy in this year’s Sundance Grand Prize-winning film Frozen River feels new. Having recently played scene-stealing roles opposite Benicio del Toro ( 21 Grams) and Tommy Lee Jones ( The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada), there hasn’t been much work since her four-year stint as Kay Howard on Homicide: Life on the Street ended in 1997. But when Courtney Hunt approached her with the role of a struggling mom who takes drastic measures to give her kids a better life, Leo knew she had something special. Played with a tenacious desperation, Ray Eddy is a character audiences will not soon forget and whom Leo believes will never leave her. Filmmaker sat down with Leo at the Sony Classics offices where she speaks candidly about her career and the role of the female actor in today’s moviemaking. — Jason GuerrasioWhat attracted you to the Ray character? Let’s cut to the chase and make very, very clear that my entire career has been sort of taking whatever has been across the table. There was no picking or choosing. I remember after we shot the short Courtney asked me if I wanted to do a feature. I said, “Sure,” and for four years I would call that woman every seven, eight months and ask, “Are we making the movie?” There’s something I understood so deeply about Ray — the mothering and the desperation, which isn’t to say that I lived through Ray Eddy’s life myself but [I’ve been in] close enough proximity in different kinds of ways to feel that I had something no one else had to bring to the film — a willingness to be a person who has made some pretty bad judgments from time to time and makes no bones about it. Courtney says in her interview that she wanted to make a film about women doing stuff, and that most films about women are talky relationship films. Do you think that’s true? Yeah — a lot of chatting with each other. Much more often we are “someones.” When I did Homicide it became quite clear that everyone thought of Kay Howard as Danny’s partner. Well, I’m sorry, but he was her partner! She was the better cop — more experienced, a better person — but they wouldn’t write it that way. But I don’t like to engage in the conversation of, “Oh, no parts for women!” From the beginning of time there have been parts for women… but they used to have men play them. [ laughs] But women are a major part of the world so our stories are out there and every once in a while we get an opportunity to do something. You played the character of Ray in Courtney’s previous short film. During the time you spent waiting for the feature, did you think about and work on the character? There have only been a couple of opportunities where the work is with me for some amount of time before I actually do it. More often it’s a remarkable handful of days and then we’re in and doing it. But with Frozen River I had the script for some time. It’s not like I would pull it out all the time and write little notes, but there is something about a character being with you through years. [The character of] Kay Howard had that. One day I was Kay Howard and four years later she and I had both grown and changed. As an actor, that’s a fascinating thing to me. I call it filtering down. My actor’s tool is myself — I go through molecular restructuring so when the molecules of Ray Eddy are with me for years in one way or another, yeah, that’s some delicious work. Like when the costume designer brought me one pair of jeans after another to the point that I finally went to K-Mart with her and when I had Ray’s jeans on I knew it. How is it to be on a successful TV show for four years and then when it ends have to go back out to find work? I could not get hired, not for anything. I couldn’t get hired to play police because they didn’t want that same policewoman, I couldn’t get hired to play victims because Kay Howard couldn’t be a victim. [ Homicide] really blocked me out of work, strangely enough. I loved the respect that I got from playing that part, but it didn’t help my career too much. When Courtney looked for money for the feature she was often told that she needed bigger names to play the leads. Did that lurk at all in the back of your mind when you did this film? “I’m going to show these people what I can do." No, you carry a grudge like that and all it’s going to do is hurt yourself. [ long pause] I think Frozen River aside, my industry is in pretty deep trouble because of that issue. There is something about “right casting” — not about how big the name is but about [an actor] being close to the character, or elevating it with [his or her] own experience and understanding. I can’t tell you the number of first-time filmmakers, people without a pot to piss in, saying, “Oh, no, we’re going to get ‘blah, blah, blah’ ” because then they can make their movie. Unfortunately “blah, blah, blah” is going to be a pain in the ass to work with, is going to bust their budget and make shooting more difficult because of their demands. And then there’s this really sweet independent filmmaking that is really about the project. Which isn’t to say that “blah, blah, blah” couldn’t play the part, but the necessity [of them playing it for financing reasons] is really dangerous for the industry. How proud were you to see the attention that the film got at Sundance? Pride is not an easy emotion to come up in me, but yeah, I’m very, very proud of Frozen River and what I brought to it. I know I made it a better film. It’s not because of me it’s a great film; it’s because of every single one of us who where there, Courtney Hunt, first and foremost. And her husband Donald Harwood, who raised the money, and every single one of those kids who froze their asses off with us and stayed in that dreadful little motel. It’s all on the screen, and that’s delicious moviemaking. Labels: Web Exclusives

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/19/2009 03:44:00 PM

MOOD SWINGS

By James Ponsoldt