FESTIVAL ROUNDUP

- Sundance Film Festival Sundance Film Festival by Noah Cowan

Berlin International Film Festival by Noah Cowan

International Film Festival Rotterdam by Stephen Gallagher

Thessaloniki Film Festival by Scott Macaulay

International Havana by Film Festival by Marco Masoni

CineQuest by Beth Kinsolving

Sundance Film Festival

Sundance 1998 will not be remembered as a particularly memorable year in the Festival’s history. No distributor shoving matches, no scandalous star moments and few ground- breaking films came to pass. And yet, with a number of serious, intelligent films, a key new venue and much better production, organization and projection, the event quietly solidified its position in the world’s festival hierarchy.

|

| Jonathan Stack and Liz Garbus' The Farm |

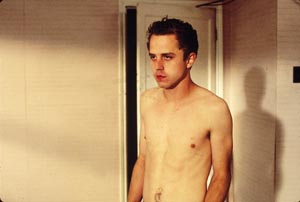

This subtle triumph was reflected in the only important cinematic trend revealed at the Festival. Found in the sidebar American Spectrum section were a collection of films by and about young men, which share a distinct and fresh cinematic vision. Tony Barbieri’s One, Jesse Peretz’s First Love, Last Rites and Eric Drilling’s River Red share an almost reactionary disavowal of the cynical, jokey, shoot-’em-up approach that has been meant to encapsulate the life stories of young males throughout this decade. Instead, they look to a cinema of long takes, exquisite cinematic framing and understated performance to reveal the minutiae which in fact determine life’s course for their subjects. Yet these three are no Bressonians; they are far too contemporary for that. In their subtle intimacy, the films are closest to Atom Egoyan or Olivier Assayas at their quietest.

In One, a man released from prison for mercy-killing his grandfather moves in with his best friend, just fired from a baseball team for attacking the manager. Only discussed elliptically, their every action and gesture suggests the pain of making decisions under subtle duress. First Love, Last Rites chronicles a young man’s coming-of-age as a visitor in a small Louisiana town. Through an enigmatic affair with a local girl and his relationship with her father, he rethinks the nature of the freedom which adulthood brings. River Red details the sacrifices made by one brother for another when confronted by an abusive father and the eventual inability of the boys to live together in the wake of their actions to help one another.

None of these films is perfect. One teeters on the edge of overcooked melodrama when it shifts focus from the friends to an overbearing father; First Love, Last Rites inelegantly employs an annoying child to remind the young lovers of their recent past; River Red’s third act unravels in a baffling set of armed robberies. And yet there is something genuinely impressive about the control and seriousness of purpose which all of these first films display.

It is also difficult to express how welcome a cinematic trend this is. If such films can help create a market for a more reflective cinema – and there are a handful of stars in them that might help this cause – then the strong foreign-language films which are having such a hard time finding U.S. screens may have a chance.

It also must be said that none of these films exactly caught fire during the Festival, as critical and industry attention were focussed on the Competitions and their gala Premieres.

While for many years the acknowledged number-one spot to premiere new American films for media and distributors, Sundance has not really reaped the full credit it deserves for launching several important non-American English-language films in its Premieres section. Perhaps that was because one seemed to appear every year – Shine and The Full Monty being noteworthy examples – that burned so hot that the Festival’s contribution to the film’s success was discounted. (How could it not be a hit?) No single meteors like these flew the skies this year, yet the Festival felt like a much friendlier place for films outside the American independent "mainstream."

The great white hope for the Monty mantle was a British production featuring Parker Posey, Jeremy Northam and Craig Chester about a writer’s changing relationships while she writes a French sex farce. Billed as the work of a modern Mankiewicz, The Misadventures of Margaret was a flat disappointment; its leaden device of switching away from the main action to re-enactments from Posey’s novel drowned the work of its excellent cast.

The Premiere that ultimately delivered was Walter Salles’ Central Station, the tale of a cynical professional letter writer who accompanies a young orphan on his quest for his father. Astonishingly beautiful to behold, many felt its epic cinematography made its emotional core difficult to access. For those of us more suspicious of Kolya-like emotional sledgehammers, Salles’ restraint was welcome. Subject to a mini-bidding war after the screening for remaining territories – Sony Classics had already bought North America prior to the Festival – it seemed destined to be another classic Sundance success story. However, Central Station is a Brazilian film, and its characters speak Portuguese. No foreign-language film has enjoyed success of this kind at Sundance, making its accolades – which continued through its triumph at the Berlin Film Festival – all the sweeter for Festival organizers.

Other Premieres couldn’t hold a candle to Salles' film. These included the deeply uninteresting gangster thriller Montana, which flogged the (already flogged) Things To Do In Denver When You’re Dead genre to death; Miramax’s uninspiring A Price Above Rubies; and the jet-black comedy The Opposite Of Sex, with a wonderful Christina Ricci and Lisa Kudrow. Director Don Roos’ script, about a bad-seed girl seducing her gay half-brother’s boyfriend, refreshingly updates the drop-dead banter and one-liners of Golden Age comedies in a way that the makers of Margaret could perhaps study next time. While many critics objected to its running cynical voiceover (by Ricci), this critic found its self-awareness quite refreshing until it (and the rest of the film) got sappy cutesy in its last act.

Many excellent films – such as David Mamet’s The Spanish Prisoner and Paul Schrader’s Affliction – already written about in this magazine made Premieres of a kind here as well.

For attending delegates, the Premieres were also associated with the very best new addition to the Festival: the Eccles Theatre. A large "gala-style" theatre, it served as a perfect launching spot for these glitzy, star-driven films and allowed for at least one large screening for the bulk of the Dramatic Competition, traditionally very difficult to access.

|

| Darren Aronofsky's Pi. Photo: Matthew Libatique |

This year’s Dramatic Competition had nothing as artistically rich and intellectually complete as last year’s In The Company Of Men. A few films came close. The young director of Pi, Darren Aronofsky, displayed a quite astonishing ability – almost absent in recent years – to not just quote from his easily identifiable influences, but to synthesize, transform and generally rethink them. The result is a daring and rich first feature about a mathematical genius who may have stumbled upon the "magic number" sought both by a gang of Orthodox cabbalists and powerful stock market analysts. His drawing together of narrative and non-narrative throughlines about mathematics feels like early Greenaway; his confrontational black-and-white futuristic cinematography like David Lynch’s Eraserhead; and his elegant cutting and dramatic pacing like Kubrick. The jungle-based score is also one of the best in recent memory. Very impressive.

Two strong films – Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo 66 and Lisa Cholodenko’s High Art – exhibit directorial control so impressive that underlying problems in both films may well be glossed over. Buffalo 66, with another knockout Christina Ricci performance, concerns a man (Gallo) just released from jail. He wants to accomplish two things on the outside: prove to his parents that he was actually away becoming successful, and assassinate the football star whose missed field goal in 1966 sent him to prison in the first place. A young tap dancer (Ricci) assists in the first and thwarts the second. Gallo is a visual obsessive: every shot is electrifyingly composed and the actual quality of the film stock – he apparently created a new process to mimic the great football highlight films from the 1960s – is something completely new. But there is a violently aggressive tone to the film – from its faux-rape and gay-bashing opening scenes, through the encounter with his parents – that feels suspiciously like confrontation for confrontation’s sake.

High Art also displays a beautifully realized mise-en-scene. Its every element – performance, design, camera – feeds into the false comfort and softness of its drugged-out milieu. A credible and sexy lesbian love story played out against the New York art-and-heroin world, High Art is strong, funny and powerful at its core, tripping up only when it uses minor characters to further its plot. This is especially true for Bill Sage’s inelegantly conceived "friend" role; he only seems to appear when there is crucial information to be imparted, dulling the impact of each revelation.

The dark horse of the Competition for me was Under Heaven, a decidedly unfashionable rethinking of The Wings Of The Dove featuring a masterful, subtle performance by Joely Richardson. The transformative power of sex – only embarrassingly acknowledged in James and the Softley adaptation – is forthright here; credit is due to Richardson and Aden Young, the powerful and enormously attractive Australian actor who invests Buck with the wonder of a young man in love. Miss Monday also didn’t make much of an impact, but its explosive deconstruction of the psychological world of a "power bitch" marks an impressive debut. In general, the Festival seemed less interested in elegant character studies such as these and the male trio mentioned above than broader cinematic gestures.

Thus, a huge buzz greeted Mark Levin’s Slam and Tommy O’Haver’s Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss. Slam is a ghetto story with a spin: the drug dealer is a poet. He saves himself in jail and comes to terms with larger society through the power of his words, especially when recited on stage. Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss is a light gay romance in which a photographer falls for a straight musician and introduces the beautiful young man to a circle which ultimately steals him away.

Both of these movies play to the balcony. Audiences hoot and holler when Slam’s poets square off in friendly competition – the scenes are electrifying – and cheer and applaud when one of many way-too-didactic political speeches issue forth. O’Haver, with great wit and style, manages to make the fundamental gay issue of straight-boy obsession a universal lesson in thwarted love – Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss came closest to eliciting the warm, ribald laughs of The Full Monty – but ultimately loses emotional depth in the process. In his depressed moments, lead actor Sean P. Hayes seems more cartoon sad than fundamentally distraught, and the final emotional resolutions in the film are distractions from the jokes.

Oddly, the other buzz film of the festival was Next Stop, Wonderland, a quirky romance set in Boston without much wit or charm. Miramax spent a great deal of money on the movie, so perhaps I missed something.

The Documentary Competition received more attention than usual this year. Cognoscenti were especially chattering over Todd Phillips'’ and Andrew Gurland’s Frat House, an intriguing film which displays some of the perils of making an expose-style documentary. These filmmakers are unabashedly focused on the kind of film they want to make, which is welcome in the current "glue-a-Hi-8-to-my-forehead" documentary climate. But the ugly episode that characterizes their first attempt at pledging never pans out in the longer, second half of the film that takes place in a different house. Unfortunately that means we get a fully-realized, brilliant documentary that lasts 25 minutes and then a still-intriguing sequel.

Also hot was The Farm, a look at a particularly oppressive Louisiana prison. Agitprop to its core, the filmmakers have made an intellectually slick and beautifully edited prisoner- rights film. But they seem to resist being up front about their motives; never do they explicitly weave tell-tale political analysis into their method. While happily subtle, the approach seems a touch deceitful.

Out Of The Past marries the struggle for a gay and lesbian student club in a Utah high school with a historical collection of marginalized gay rights leaders. The two strands do not fully come together, but the film has an honest political energy which is enervating and spurs reflection.

Also of note was Vicky Funari’s harrowing biography of a Mexican maid, Paulina, and Iara Lee’s forthright, hip explication of the current electronic music scene, Modulations. I also loved Human Remains, Jay Rosenblatt’s short-form meditation on the private lives of this century’s cruelest dictators.

Grand Prize Winners were Slam and The Farm. The Filmmakers’ Trophies were awarded to Native-American drama Smoke Signals and Divine Trash, a documentary about John Waters’s muse. The Audience also chose Smoke Signals and voted for Out of the Past as their favorite Documentary. Directing awards went to Pi and Moment Of Impact, about a daughter’s relationship with her comatose father. Cinematography awards went to Jimmy Smallhorne’s 2by4 and Barbara Kopple’s stultifying Woody Allen film, Wild Man Blues. The Waldo Salt screenwriting award was won by High Art and Andrea Hart, the star of Miss Monday received Special Recognition from the Jury.

The Berlin International Film Festival

Trade magazine writers have jokingly claimed for years that they preprint their Berlin roundup articles with the header "Industry Disappointed At Berlin." This year was no exception; see Variety especially.

Stacked up against this continuous din of bad news is a genuine enthusiasm for the Berlinale among American independent filmmakers, curators and critics. So what's going on? Are the suits trying to spoil the party?

The trades attack the Festival on three fronts – the biz, the stars and the films – and it is often vulnerable in each. I have never attended a Berlinale when it has failed in all three areas, but nor has it succeeded to be completely satisfying in years. Budget cuts, bad timing and a certain administrative stiffness have contributed to its problems, but the Festival’s troubles are still overstated by the trades.

With a film culture explicitly dominated by America, and the two most important cultural and commercial events on American soil –Sundance and the AFM – straddling the Berlinale, business has been slowing down for years.

When the Americans backed away, the vacuum was filled by the aggressive European boutique sales agents – Fortissimo, Christa Saredi, Film Four and Celluloid Dreams have consistently seen brisk business there – until they now dominate sales of the Festival’s Competition entries. This year added another problem to the mix: the East Asian currency crisis caused those buyers to remain at home, and Berlin was traditionally where they bought smaller, specialized art films.

Yet the Market is nowhere near expiry. Extremely well-organized and efficient, it will likely bounce back when European cinema fetches high prices again abroad. The sheer American-ness of the AFM will make a shift of such films to L.A. impossible.

Berlin’s problem with stars is a devil of its own making. In response to the precipitous decline in East European and German filmmaking standards following the end of the Cold War, Berlin looked more explicitly to the studios – they were always present in a small way – to fill the gap with their Christmas Oscar-release films. The Festival gives their biggest movies an art imprimatur for their European launches, and the only complaints come from American journalists, frustrated by all the old news. But such launches don’t really work unless the stars come. Otherwise everybody – but especially the cutthroat European press – gets pissed off when it looks like the Berlinale is just being exploited. This year was particularly bad, with Robert DeNiro the only major name who managed to make the trip from at least seven major star-driven films.

The quality of the films presented at the Berlinale is a subject of much debate. There have been serious problems in all three major areas of the Festival’s programming – the Competition, the Forum and the Panorama –and yet only a fool would suggest that Berlin is no longer a top echelon Festival. It consistently provides a showcase for films (if not a curatorial direction) that describes something important about the state of current cinema.

For the Competition, the dearth of top-drawer German and East European films is most devastating. The French and Italians hold or adapt their production schedules for Cannes and Venice. The Americans bring already released films. That leaves Asia and Latin America. And, no surprise, that’s where the "discoveries" of the Berlinale have come from in this decade (even if Hollywood has taken home the bulk of the prizes).

Central Station by Brazilian Walter Salles had already been vested with its art-house crown at Sundance; its Berlin Golden Bear acted merely as a reinforcement. Its success follows last year’s much less interesting Berlin discovery from Brazil, Oscar-nominee Four Days in September. And yet this is a signal that a renascent South American cinema could help Berlin’s fortunes, especially with Cannes ignoring the continent of late.

America, as usual, weighed in heavily with Jackie Brown, The Big Lebowski, The Gingerbread Man, Great Expectations, Good Will Hunting, The Boxer and Wag the Dog on offer. Jackie Brown and The Big Lebowski were easily the most popular with critics and the public.

Usually Berlin provides many of the year’s most important films from Asia. This year, virtually all were interesting disappointments. The "out" gay Hong Kong director Stanley Kwan’s first "out" gay film concerns the complicated relationship between three men after the death of one of their wives. Enigmatic and intriguing at first, it gets increasingly banal as time wears on. Lin Cheng-sheng’s first film, A Drifting Life, was one of the finest (and most difficult) films to emerge from this newest generation of Taiwanese cinema, so perhaps expectations were too high for Lin’s beautiful but rather static new melodrama, Sweet Degeneration.

Joan Chen’s Xiu Xiu is a strange film, sometimes looking like a tribute to Chinese exhortation films of the 1960s and sometimes like Chinese designer ethnic garbage. Its central relationship – between an intellectual town girl sent down to the countryside during the Cultural revolution and a local eunuch horse master – is a warm one but Chen subverts their story with a myriad of unnecessary political interventions and bizarre design choices. (For example, about 20 plastic flowers are attached to the Steppe grasses; incongruous to say the least, but one Italian critic thought it might be a nod to Chen’s film debut as a child star in which much the same effect was used.)

The Festival’s two most controversial films were, for this critic, also perhaps the Festival’s two best: Neil Jordan’s The Butcher Boy and Michael Winterbottom’s I Want You. Jordan’s film is an astonishingly faithful adaptation of Patrick McCabe’s frenetic novel about a hyperactive boy who causes mayhem and murder in the pursuit of true friendship and revenge. Paced like a lit roman candle, Jordan takes us on a frighteningly intense journey inside the boy’s head; we move from pure fantasy, sometimes featuring a radiant Virgin Mary portrayed by Sinead O’Connor, to restorative narrative sequences. For all of its many achievements, The Butcher Boy is foremost a landmark in film pacing.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Big Film God for creating Michael Winterbottom. He is one of the very few young filmmakers whose every work contains an intellectually rich backbone fleshed out with large-scale narratives. Even when he delivers an ultimately unsatisfying film, like last year’s Welcome To Sarajevo, there has been real thought about the marriage of form and story. (In Sarajevo, Winterbottom created his own "language" to understand Bosnia; a combination of news footage, documentary video, traditional 35mm cinematography and an equally diverse set of editing choices, it attempted to mirror our own mediated analysis of that tragedy.)

His newest work, I Want You, was brutally attacked in Berlin from many quarters as a familiar subject and a cold intellectual exercise. These critics are idiots and must be authoritatively ignored. The film turns on three startling revelations that bring many stories together, so a convincing precis is difficult. Suffice to say that four characters – a couple reunited after the man’s nine-year imprisonment, and a Bosnian brother and sister – in a seaside British town cross physical and emotional paths. Each must face up to their various melancholy desires, many of which seem to directly follow from the famous Elvis Costello song of the same name. Finally a meditation on ideas of interpersonal justice, especially in terms of self-sacrifice, it leaves you trembling but not weeping. Shot by Slawomir Idziak, Kieslowski’s long-time cameraman and one of cinema’s greatest filter artists, the film’s every image takes on epic proportions. This jaw-dropping intensity is matched by the quiet hunger exhibited by two very fine young actors, Rachel Weisz and Alessandro Nivolo, in the lead roles.

The French work was bleak. The new Jacques Doillon, especially after the creepy but brilliant Ponette, was a shockingly dumb wank about a director and his nubile acolytes. Two French musicals were well-liked by those same morons who hated Winterbottom. Alain Resnais’s Same Old Song is a standard-issue collection of "amants in Paris," except every few minutes someone lip synchs to a famous French pop song to display their inner feelings. Cute and clever for about 15 minutes, the film becomes tired in the second hour. Much worse was Jeanne and the Perfect Guy, a kind of French "Rent" with AIDS patients and oppressed immigrants breaking into songs about their struggles. But, you know, it’s still France, so the lead character is a foxy nymphomaniac.

Two pretentious Australian films rounded out the field. The Boys seeks to psychologically "explain" the actions of three brothers accused of gang rape; its a dubious exercise made baffling by a shuffled time sequence. Only Toni Collette’s spunky performance as a tough trailer trash tart holds interest here. The Sound of One Hand Clapping sees a woman returning to Tasmania to confront the demons suffered by her immigrant parents; the resulting ham-fisted melodrama is embarrassing.

The Panorama – the parallel, "Information" section beside the Competition – has long been a happy home for American independents, particularly gay ones and documentarians. This year was no exception with Brian Sloan’s exuberant I Think I Do and Jochen Hick’s unfocused Sex/Life In L.A. representing the former, and Susan Muska and Greta Olafsdottir’s The Brandon Teena Story – the incredible tale of a woman living a man’s life, complete with girlfriends, until her/his murder as a young adult – and Timothy Greenfield-Sanders’ biographical Lou Reed: Rock And Roll Heart, the latter.

This consistency has its drawbacks. When the Panorama began, gay and lesbian cinema was just emerging. Now it is much closer to the mainstream, so continuing to focus on this work may not be as vital a mission for the section. The world of documentaries has also been radically altered over the years, and its changes perhaps are not always fully acknowledged here.

This year’s top films included Kichiku, which updates the Japanese Trotskyist pink films of the 1960s with a wild, splatter-gore third act. Sue, Amos Kollek’s intense and beautiful character study of a woman spiritually lost in Manhattan features an award-caliber performance from Anna Thompson. And the Sicilian Toto Who Lived Twice is a black-and-white orgy of goat humping and blasphemy which could well be merely dumb (but might also be profound).

In the same spirit as the Director’s Fortnight in Cannes, The Forum was formed in opposition to the Competition during the heady days of Paris ‘68. Its roots are looking a little gray today. Unreconstructed Marxist documentarians and radical postmodern posturing are still on the menu. Newer innovations, like a Japanese animation night, take place even if the work doesn’t merit it.

Still, of all the sections, the Forum seems most willing to seek out new work. Its huge collection of new Japanese and Korean films is a timely reminder of the vibrancy of these national cinemas. Of the Japanese films, Sabu’s Unlucky Monkey is the triumph: a violent farce with a wicked sense of humor and an iconoclastic take on the true nature of love. The revelation from Korea was Kim Ki-Young, a filmmaker from the social problem school with a Sirkian flair, who was the subject of a small retrospective this year.

However, the finest film in the Forum, and perhaps the most fully satisfying film of the entire Festival, was not from Asia, but northern Russia. Lidija Bobrowa’s In this Country, a finely detailed portrait of a traditional collective farming town undergoing the subtle changes slowly blowing in from the new Russia, is a textbook example of perfectly conceived metaphor and directorial control. It reminds us of the beautiful precision that was the hallmark of Soviet filmmaking and a reminder too of what the Berlinale once offered in droves.

International Film Festival Rotterdam

The 27th International Film Festival Rotterdam, the largest film showcase in the Netherlands, unspooled January 28 through February 8 to record attendance. The fest reported 275,000 admissions, a 10% increase over 1997, despite the fact that there was one less venue this year. Credit must be given to director Simon Field, a British expatriate in his second year at the helm of this massive event, and his extraordinary staff for coordinating what is undoubtedly one of the best organized festivals in the world. Rotterdam is both easy to navigate – all of the fest venues are within walking distance from each other – and, for a New Yorker, disconcertingly friendly. The fest’s ticketing process is also apparently trouble free, an achievement at a fest of any size.

|

| Jesse Peretz's First Love, Last Rites, at Sundance and Rotterdam. Photo: Jesse Peretz |

The programming is also incredibly diverse: unlike most other major international film festivals which are geared exclusively to the theatrical film market, Rotterdam’s Main Program of recent features is virtually dwarfed by its Exploding Cinema sidebar, which includes surveys of underground and avant-garde cinema, multi-media installations, lectures and concerts. Among its highlights were terrfic late-night shows by D.J. Spooky, Mouse on Mars, and D.J.s from London’s Outcaste label; an exhibition curated by producer Michael Shamberg at the Witte de With gallery entitled Home Screen Home, featuring compilations of video art, music videos and short films screened on monitors informally scattered throughout a space decorated with eye-popping wallpaper designed by John Baldessari; and the day-long event, A Day and Night at the Rex, which took place in "the last real sex cinema in Holland," and consisted of performances by Maria Beatty, Michael Atavar, and Ron Athey (the subject of Catherine Saalfield’s feature documentary, Hallelujah, which also premiered), along with screenings of Kirby Dick’s Sick and assorted other transgressive media.

While the Exploding Cinema program (and other sidebars like The Cruel Machine – which included close to 30 features dealing with the theme of cruelty – and the selection of Italian exploitation pictures) crystallized the fest’s adventurous atmosphere, the focus of the event is nevertheless the films premiering in the Main Program, the Tiger Awards Competition, and in its selection of Third World films produced with funding from the Hubert Bals Fund. Between them, these three sections of the festival comprised over 160 features.

Among the highlights of The Tiger Awards Competition, which included 14 features by first or second-time directors each vying for one of three $10,000 cash prizes, were Canadian director Gary Burns wry comedy Kitchen Party (subsequently invited to New Directors/New Films); Jesse Peretz’s moody, Fipresci prize-winning First Love, Last Rites and Mexican helmer Carlos Marcovich’s extraordinary pseudo-documentary Who The Hell Is Juliette? (both of which screened at Sundance); and Stefan Ruzowitzky’s Die Siebtelbauren (The One-Seventh Farmer), a Tiger Award winner. Ruzowitzky, who hails from Vienna, describes his second feature as an Alpine western, but this highly stylized tale about seven servants who inherit the estate of their dead lord, igniting the wrath of the neighboring landowners, is also a new and utterly ironic take on the Heimat film.

The festival’s Main Program included a number of premieres, most notably the fests’s Audience Award winner The Polish Bride by Dutch director Karim Traïdia and two poignantly understated films, Les Sanguinaires by Laurent Cantet (France) and Tamas and Julie by Ildiko Enyedi (Hungary), both of which were produced by France’s Haut et Court and commissioned for the Arte series 2000 Seen By...; the series promises seven more films (by the likes of Walter Salles, Alain Berliner and Tsai Ming-liang) dealing with the "human condition" at the close of the millenium. The vast majority of films featured in the Main Program, however, were not premieres; the section functions primarily as a festival-of-festivals overview of the prior year’s crop. A number of films in this section are also released theatrically in the Netherlands following the festival, all benefiting from the wealth of publicity the fest generates domestically.

While there were a great number of acclaimed films represented in the Main Program, I was particulary struck by Tony Gatlif’s Gadjo Dilo. This infectiously joyous film from the director of Latcho Drom about a young Parisian’s journey into the heart of a Romanian gypsy community will be released stateside by Lion’s Gate this summer. Also notable was Japanese director Saito Hisashi’s debut feature, French Dressing, in which a strange relationship develops between a depressed, narcoleptic schoolboy and the teacher who rapes him to prevent him from committing suicide. (The teacher wants to give the boy a reason to live: hate.) The film’s assured, deadpan delivery undercuts its transgressive subject matter to create a haunting portrait of teenage abjection and marks Hisashi, a veteran screenwriter of TV dramas in Japan, as a director to watch. I also caught up with Youssef Chahine’s Destiny, a prize-winner at Cannes. Picked up jointly by Cinema Village and Leisure Time for domestic release, Destiny is a sprawling melodrama set in the twelfth century that deals with the consequences of Egyptian fundamentalism. While its convoluted plot is often incoherent, its sumptuous cinematography (by Moshen Nasr) is never less than mesmerizing.

|

| Ildiko Enyedi's Tamas and Juli |

The Hubert Bals Fund (named after the former fest director), which provides funding to filmmakers from the Third World, had a part in the completion of 13 films screening in Rotterdam this year – including Francisco Athié’s well-received premiere, Fibra Optica (Mexico), Dariush Mehrjui’s Leila (Iran), Zhang Yuan’s East Palace, West Palace (China), and Ademir Kenovic’s acclaimed Perfect Circle (France/Bosnia). The Fund is an important resource for filmmakers in underdeveloped countries and is further testament to Rotterdam’s reputation as an advocate of committed cinema.

The festival’s advocacy is perhaps exemplified by CineMart, a unique initiative that this year brought 253 producers looking for production funds together with 142 distributors and 29 television executives from around the world. Unfolding in the Rotterdam Hilton, where over 2,000 meetings were taken by participants representing 53 film projects in just five days, CineMart is an increasingly vital incubator of independent films. (Participating U.S. projects were sponsored by the Independent Feature Project.) Among this year’s market success stories were Rosa von Praunheim’s The Einstein of Sex: The Life and Work of Magnus Hirschfeld, Tsing Ming-liang’s Time Zone, and Lorenzo O’Brien’s Teenangels – each of which secured enough financing to start shooting.

Although it takes place concurrently with the festival, which producers are free to attend if they can find the time, CineMart is not part of the festival proper. One could easily attend the festival without crossing paths with a single industry exec among the thousands of Dutch cineastes. But festival guests are free to lounge in the lobby of the Hilton, where CineMart execs are virtually sequestered, and easily take informal meetings over a quick cocktail.

Rotterdam may be primarily an audience festival and a launching pad for domestic theatrical releases, but its multifaceted programming, together with CineMart – even in what was widely considered a year of lackluster premieres – make for an enormously satisfying event with something for just about everyone.

Thessaloniki Film Festival

Walking out of the Olympia Theaters, the large, plush halls where Competition films at the 38th Thessaloniki Film Festival unspooled, one could gaze out towards the ocean at the seaships and tankers sitting shrouded under dramatic folds of fog and mist. The view recalled nothing so much as a scene from a film by Greece’s premiere art-film export, Theo Angelopoulos, director of such works as The Beekeeper and, yes, Landscapes in the Mist. And by turning one’s head to the side, one could track along the water towards the shoreline where, this year at Thessaloniki, there was Angelopoulos himself, along with his great d.p., Yorgos Arvenides, shooting his latest film with actor Bruno Ganz. Visitors to this year’s Festival – and Europe’s 1997 cultural capital – were invited on set to watch Angelopoulos direct as his small crew moved around the town, from the overcast seaside to the neon-lit ouzeris, keeping watch over the Festival during its ten-day proceedings.

|

| Todd Verow's Little Shots of Happiness. Photo: Todd Verow. |

A safe haven for art cinema, Thessaloniki, held every November in this affluent Northern port city, screens a few obligatory Hollywood films – The Edge, The Peacemaker – but concentrates mostly on both new and retrospective director-driven filmmaking. Indeed, most remarkable about Thessaloniki is its attention to filmic surveys. This year, one could see complete retros of Claude Chabrol, Arturo Ripstein, Takis Kannellopoulos, and Manoel De Oliveira and several films each by Errol Morris, Tsai Ming-liang, Aleksandr Sokurov, and Tony Gatlif. And, given its geography, Thessaloniki pays special attention to new Balkan cinema with a special sidebar section.

The Competion, programmed by Michel Demopoulos, featured mostly young directors with their first or second films. Dervis Zaim’s Somersault in a Coffin was announced as the first independent film produced in Turkey. The neorealist inspired no-budget film depicts a homeless man who one day steals a prized peacock from the state castle. The film has something to say about politics and the media but most striking was its fusion of neorealism, narrative ellipses, and eerie expressionist gestures. Also in Competition was Lee Chang-dong’s Green Fish. In some ways a standard-issue crime melodrama, complete with a nightclub singer femme fatale and dueling gangster bosses, the Korean film was graced by a precise visual style and a sympathetic social conscience. Also in Competition were U.S. indie In the Company of Men, Shane Meadows’ poignant but overrated TwentyFourSeven, and Croat filmmaker Zoran Solumun’s rather thin Tired Companions, an anthology film about refugees fleeing the former Yugoslavia. The jury awarded its top prize to Australian Sue Brooks and her Road to Nhill; Somersault in a Coffin received the Special Jury Award.

Thessaloniki also features a National Competition that promotes the year’s crop of Greek films. (Next year, the National Competition is to be abolished and some worry that this will have a deleterious effect on the Greek film industry.) One of the Festival’s popular favorites, Renos Haralambis’ No-Budget Story, was found in this section. The comedic tale of a filmmaker struggling against the Greek state subsidy system, the film drew a young audience and enormous laughs for its skewering of precisely the sort of highbrow art pics helmed by Angelopolous.

More than a little inspired by In the Soup, No-Budget Story was shot on video and transferred to black-and-white film. The likable Haralambis worked as a "trash-TV" actor and called in favors to fund this gentle satire. "I had submitted 11 scripts to the Greek film center," he said. "You have to be older than 35 [to get funded]. It takes one year to write the script, two years for them to read it, and then you wait one year to start shooting. If the government changes, maybe you lose your money!"

Energized by the American no-budget movement ("Americans are cool; Greeks are not cool – we are heavy," Haralambis said), the director "took small bits from ten movies – In the Soup, Barton Fink, Living in Oblivion, Smoke" – and reworked them into humorous set pieces laced with Greek in-jokes. For Haralambis, the highlight of the Festival was a conversation with Chabrol, who liked his film and offered to try to sell it to French TV – "Angelopoulos was the translator!" Haralambis laughed.

In addition to the competitions, Thessaloniki boasts a huge section of young cinema, New Horizons, curated by legendary festival programmer Dimitri Eipides. "Small independent festivals around the world have taken up the task of making film culture," said Eipides. New Horizons is comprised, he says, "of films that have distinguished themselves in other festivals, and work by first-time directors." He adds, "To me, both are important."

It was here, accordingly, that I caught up with Tsing Ming-liang’s The River, winner of the Silver Bear at the 1997 Berlin Film Festival. The story of a young teen suffering a painful and inexplicable infection after appearing as an extra in a low-budget film, The River, much like Todd Haynes’ Safe, generates enormous empathy and compassion for a protagonist defined by the most minimal of means. Cleverly manipulating a familiar set of themes and elements – storms, rain, and the fractured nuclear family – Taiwan’s Ming-liang has made a formally controlled, emotionally wrenching masterpiece. His last film, Vive L’Amour was distributed here by Strand; let’s hope that this even more accomplished film can get play in the States.

"Women on the verge" was a popular theme in New Horizons. In Yolande Zauberman’s Clubbed to Death, a young French girl falls asleep on a bus, wakes up at a rave concert, and winds up stealing the black lover of club diva Beatrice Dalle. Unfortunately, Clubbed to Death’s filmmaking wasn’t strong enough to lend insight to its trendy storyline. Better was Carine Adler’s Under the Skin, in which a sex-obsessed London clubgoer struggles with the death of her mother. Marred by a saccharine ending, the film still impresses by virtue of Samantha Morton’s fierce performance and Adler’s captivating blend of beautiful, Nan-Goldenish cinematography, jarring jump cuts, and haunting fantasy sequences. However, I liked best of all Todd Verow’s Little Shots of Happiness, a no-budget, tape-to-film story of a young office worker who turns to booze and casual sex after a split with her husband. Sloppily mixing Fassbinder and Warhol to a techno beat, Verow’s film has wit, raw energy, and tremendously endearing performance by Bonnie Dickenson.

Other New Horizons titles included Larry Fessenden’s creepily compelling urban vampire flick Habit, Rachel Reichman’s cool look at labor and libido, Work, and Baille Walsh’s transfixing story of New York transsexual Consuela Cosmetic, Mirror, Mirror. Also featured in the program was Robert Guediguian’s Marius and Jeanette. Produced for under $1 million by France’s Agat/Ex Nihilio, the film scored at the French box-office by lacing a simple lonely-hearts romance with a series of witty and lighthearted meditations on French class politics. Charming and accessible, Guediguian mixes the personal and the political in a way that eludes most American independents.

Thessaloniki is not much of a business festival, although its careful programming and beautiful location draws a larger group of European producers and distributors than one would expect. An American independent probably won’t find a deep-pocketed foreign sales agent here; a sale to Greek television is more likely. Still, the Festival’s focus on art cinema is so strong (Eipides notes that the Fest was an early champion of Greenaway and Hal Hartley) and its audiences so receptive that a presence at Thessaloniki can offer younger filmmakers the chance to begin building the international reputation needed to sustain the continued production of challenging work into the future.

International Havana Film Festival

Standing before a capacity crowd in Havana’s cavernous Karl Marx Theater, festival Director Alfredo Guevara officially kicked off the opening ceremony for the 19th International Festival of New Latin American Cinema with a long, lyrical welcoming speech laced with references to history, ideology, politics, religion, the arts and, of course, film. The breadth of Guevara’s speech set the tone for a festival that would not only provide a showcase for Latin American film and related initiatives, but would also prove itself to be a journey through Cuba.

Just moments before the ceremony I had been transfixed by the vintage American cars, specimens of a bygone era, that were negotiating their way through the great crowd of waiting people who had amassed in front of the theater. A screenwriter might have conceived this scene as: "Ext. 1950s Hollywood Movie Set – Evening." But the ‘55 Buicks and Hudson Hornets were mostly beat-up relics and they were interspersed with clunky Soviet-made Ladas; the anxious onlookers wore modest clothes, nothing that resembled period costumes; and with a theater named after Karl Marx... this was at least one economic system removed from the orbit of Hollywood.

And yet there was this feeling of being on a movie set, like an extra in one of the world’s longer works-in-progress, the 39-year-old brainchild of that renowned first-time director, Fidel Castro. This was, after all, Castro’s revolutionary Cuba, an experiment in socialism that desperately needs finishing funds to surmount a growing economic crisis – a crisis brought on by the combined effects of the loss of Eastern Bloc patronage, a long-standing U.S. embargo, and the inability of Cuba’s creaky economic system to adapt and prosper.

I couldn’t help but wonder why, during these worst of times, Cuba had decided to go to the trouble and expense of rolling out the red carpet for ten days (December 2-12) as host of a cultural event that not only featured film, but also showcased concerts, plays, exhibits and book readings. Were there not more pressing issues to tackle? But as the festival unfolded, I began to understand that hosting this event was more than mere indulgence.

Cuba founded the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in 1979, when its film industry was prospering, and in so doing it had established itself as a beacon for Latin American film; now, faced with an economic crisis, Cuba felt that it was important to show its resilience by continuing to host the event. Besides, what better way to get positive publicity than to hold a film festival? And now, more than ever, Cuba was relying on its image as a fun-loving, balmy, beautiful (though run-down) and foreigner-friendly country to attract tourists, who would provide Cuban coffers with valuable hard currency.

And there were other reasons for Cuba to hold the festival. In addition to drawing the media and tourists, the aim was to lure potential outside investors who might give a shot in the arm to the cash-starved Cuban film industry. Nor was the festival audience limited to foreign tourists or film industry types, as attested by the thousands of Cubans who attended the opening ceremony. Cuban people have a genuine knowledge and love of film and there would have been much grumbling if the government had nixed the show. When Fidel came to power in 1959 he declared that cinema was the most important form of artistic expression. Prior to 1959 Cuba was an important market for foreign films (seven million Cubans produced a weekly average of one and a half million moviegoers), but it lacked a homegrown film industry. This changed on March 24, 1959, with the first cultural decree of the revolutionary government which created the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) under the leadership of none other than Alfredo Guevara, a former classmate of Castro in his student days. Guevara stated that his mission was to use ICAIC "to demystify cinema for the entire population; to work, in a way, against our own power; to reveal all the tricks, all the recourses of language; to dismantle all the mechanisms of cinematic hypnosis." This mission has been facilitated by the virtual monopoly ICAIC has had on Cuban filmmaking since its inception, allowing it to manage the country’s production of animated cartoons, features, documentaries and newsreels, as well as run the Festival of Latin American Cinema.

Festival Vice-Director, Ivan Giroud, describes the Festival of Latin American Cinema as being "a festival for Cubans. The Cuban public is film educated, so this is a festival which puts them in the center." He adds that it’s the only festival in the world that has half a million viewers in 10 days, the average capacity of each theater being 700-1500 seats.

As Cuban moviegoers are generally accustomed to seeing a wide range of films in theatres and on television (often accompanied by television programs about film history, language and technique), they form a discerning audience and have come to expect a diverse program. This is one of the reasons festival programmers make an effort to include films from all over the world through retrospectives, sections dedicated to films from particular countries, and special screenings of recent or classic Cuban and non-Cuban films. The programmers even took a broad view as to what constitutes Latin American cinema by selecting three films from the United States to be included among the 100 films in competition. Men With Guns, the latest effort by John Sayles, for instance, qualified because it was shot entirely in Mexico with mostly Spanish dialogue and was based on a novel by Francisco Goldman.

Although there was not an empty seat during the screening of Sayles’ latest film, it received a mixed reaction. The film follows the story of a sheltered Mexican doctor who goes searching for the idealistic former students he sent out to work as medics in remote areas inhabited by destitute and oppressed indigenous tribes. What the doctor finds is a hard dose of Mexican social reality: military brutality and co-option, civilian apathy and ineffectual priests. While the film set out to be a kind of mystery with a social conscience, it came across as being overly pedantic and consequently drew a number of laughs in the wrong places by the mostly Cuban audience.

In order to make the most of my time, I often relied upon the recommendations of the extremely helpful festival staffers to determine which films were a must-see. The rule of thumb I was given is that Argentina, Brazil and Mexico usually have the best film crops, probably because these are the three biggest countries in Latin America and so they tend to produce the most films.

One of the Argentinian films I saw, Martin (Hache), was being touted as the best feature produced in that country in the last ten years. Directed by Adolfo Aristarain, Martin (Hache) is about a solipsistic director who refuses to take responsibility for his estranged teenage son ("Hache" stands for junior) or for the commitment-seeking, substance-abusing girlfriend who is some 20 years younger than he is. Although the cast was solid, the characters generally came across as static and self-absorbed and did not elicit empathy. Still, the film took first prize in the festival, it won the third most votes from the audience (surveys were passed out at each screening), and eventually made it to the World Cinema program at Sundance.

Another audience favorite and winner of the prize for best screenplay, was the thriller Ceneizas del Paraiso (The Ashes of Paradise). Also from Argentina, this thriller by Marcel Pinero revolves around the investigation of the mysterious assassination of a beautiful woman which implicates three brothers, each of whom confesses to the crime and claims sole responsibility. While Ceneizas del Paraiso was reminiscent of The Usual Suspects and L.A. Confidential in its effective use of suspense and mystery, the essence of the film was firmly rooted in Argentina and its characters, places and themes.

From Mexico there came a powerful and entertaining film that crossed the line between fiction and documentary. Carlos Marcovitch’s Quien Diablos Es Juliette is about how a Cuban prostitute, a Mexican model and a director came to meet during the shooting of a music video in Cuba, and the profound influence this meeting had on all their lives. Marcovitch’s film left me with a vivid impression that lingered on and fully impacted me when I was later shown the Malecon, a coastal road on Havana’s north side, where prostitutes in their teens and twenties stand like cones at ten-yard intervals along a five-mile stretch, struggling to earn U.S. dollars by selling themselves to cruising tourists, while their boyfriends hang out in the background, freelancing as pimps.

One of the Brazilian films in competition was a compelling low-budget feature entitled Un Ceu De Estrelas (A Starry Sky), which garnered four awards, including the prize for best first film. Un Ceu De Estrelas is about a woman whose ex-fiancee refuses to let her go and traps her in a physical and emotional cage. Amaral said that she made the movie trying to avoid the classic, Syd Field screenplay structure, where the protagonist must have an arc, because that does not reflect the way Brazilians are. In her view, Brazilian protagonists are not so much agents of change, as characters who react to circumstances and inescapable situations. Amaral effectively relays this point of view by having her principal female character stare straight into the camera at the end of the film with the hard, helpless look of a person who has nowhere to go.

The economic crisis has hampered ICAIC’s efforts to boost domestic film production, and consequently only three feature films were produced by Cuban directors in the last year. Among these was Amor Vertical by Arturo Soto, a pleasing and uncomplicated story about a young couple looking for a place to make love. "In making Cuban films," reasons Soto, "one must create something with universal appeal and look at international markets because there is no option, there is no market here." To his credit, Soto is one of the few Cuban directors who have succeeded in attracting foreign capital, and it was after he obtained financing from French and Brazilian companies that ICAIC agreed to provide the balance of his budget. ICAIC’s shortage of funds to make movies has forced both novice and veteran Cuban directors to learn how to pitch their projects. This has also caused some rivalry between the older and younger Cuban directors. Soto explained the situation: "Old directors are used to working on state subsidized films, through ICAIC. There was a certainty of getting a film made if you wrote the script. There was no need to look for money. Now, with the crisis, the rules have changed. Directors have to knock on doors. Young directors were not accustomed to doing this either, but they adapted more easily. And we feel less humiliated asking for money."

For Cuban documentarians the situation is at once more promising and more desperate. Melchior Casals, an experienced documentary filmmaker who has worked with ICAIC for many years, described the contradiction: "Young people, because they work freelance, do their documentaries without state controls, they have more freedom of expression. They shoot mostly on Hi-8, not broadcast quality, working on weekends, nights, when they have time off their jobs. And I think these filmmakers have done some great work.

Casals then went on to explain the downside: "The ICAIC, the state film industry in Cuba offered something unique in Latin America, with perhaps the exception of Brazil and Argentina. It offered the possibility of working all year round. I used to make four documentaries a year, some very critical of Cuba, dealing with the problems of socialism. They have been shown in all of Cuba, were approved by the government and had no censorship problems. Since 1992, the beginning of the crisis, I haven’t made any documentaries. With the embargo it is impossible to do this kind of documentary. To get financing now, one has to do a film with guaranteed distribution, or a documentary that has a guaranteed sale."

ICAIC is trying to address the hardships confronting the Cuban film industry by making do with less resources and taking advantage of new technology. During the festival Guevara announced the creation of a video department at ICAIC, where documentary film can be made. ICAIC is also trying to extend its international reach, perhaps in the hope of drawing more foreign investment. Ivan Giroud explained that ICAIC was studying how to re-introduce MECLA (the market component of the festival, which was not held this year). "We want to redesign the market. We want to convert it into a market for projects, works-in-progress, scripts. It’s a model that’s based on the Rotterdam film festival, but geared toward Latin American film festivals."

There were a number of non-ICAIC initiatives at the festival. News of the creation of a $15 million dollar fund for Latin American film was received enthusiastically. A newly formed Association of Latin American Documentarians (ADAL), based in Venezuela, distributed its founding charter and held a meeting to discuss ways for the organization to link Latin American documentary filmmakers, and to help them produce and distribute their works. Sundance Programming Director Geoffrey Gilmore attended the festival, and brought along a number of directors and producers to participate in panels that discussed ways to promote cultural exchanges between film communities and to support independent filmmaking around the world. And there were dozens of producers and directors scouting Cuba for their next project, inquiring into the cast, crew and facilities available for production and post-production. How many of these projects will materialize into coproductions with Cuba is anybody’s guess, but it may be Cuba’s only hope for keeping its film industry afloat, at least in the near future.

Pastor Vega, a veteran Cuban director who has spent the last two years searching for funds in Europe and Latin America to make his next movie, offered an apt comment regarding the Cuban work-in-progress: "This is a society trying to keep alive the most important values of the socialist system using the capitalist system. And that is very experimental. It is difficult to see what the result will be in the near future." Whatever the near future holds, the festival certainly deserves its place in the sun.

Cinequest San Jose Film Festival

The road to San Jose is undeniably paved with good intentions. In its eighth year, Cinequest San Jose Film Festival has probably gotten about as big as it’s going to get – and should, if anything, look to downsize in the future.

With six enthusiastically solid days of programming, multi-focused Cinequest offered quite the spread. Events included big-name-infused tributes, panels, and seminars; a slew of features, shorts, and documentaries ranging from international to local, classics to special interest; and a digital section of presentations, showcases, and discussions launched with a lavish film and technology awards party.

To kickstart the festival, Cinequest screened the documentary Trekkies, an amused, rather benign look at Star Trek fans/fanaticism, with the short Kid Nerd, about nerds all grown up – either into or out of their nerd-dom. As it turns out, the playful opening night neither set nor contradicted the tone of the festival, but, then again, one would be hard-pressed to identify the tone of the festival. The programming was ambitious to say the least. In less than a week, over 60 films were screened in six wildly different categories.

As is obvious, the programming couldn’t have been more broad, and therein lies the problem. The dizzyingly diversified offerings of Cinequest made for a festival that felt scattered and indecisive. With a net so wide, few of the catches made much of an impact. Dramatic competition films My Heart is Mine Alone and Empty Mirror felt glossy, over-produced, and stiflingly pretentious; Gen X-targeted Anarchy TV and Nothing Sacred just seemed tired. The better documentaries like Gutter Punks, a candid, heartfelt, and resonant look at homeless teens in New Orleans; Baby, It’s You; and My America (or honk if you love Buddha) have all received play at other festivals.

Unlike the choke-hold that Sundance has on Park City, Cinequest treads more considerately on San Jose’s rather sedate downtown. Existing symbiotically rather than imperialistically, the festival ranks among the most well-mannered and self-contained. Strong attendance day after day, event after event, was testament to its loyal, if largely local, following. The two theaters in which nearly everything took place were spitting distance from one another, making for a highly convenient, foot-friendly experience. Past, present, and potential repeat filmmakers who had, did, and hoped to screen their work again at Cinequest lauded the treatment they’d received at the festival, and indeed, Cinequest makes it a priority to foster that small-town, love-thy-neighbor, unlock-thy-door warmth. For filmmakers lost in the festival shuffle, Cinequest must feel like home.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →