FESTIVAL COVERAGE  Friday, January 15, 2010

PALM SPRINGS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL |

By Graham Flashner

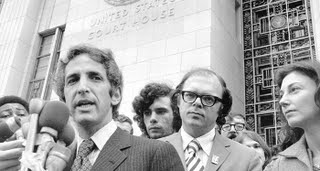

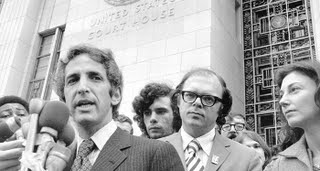

Now in its 21st year, the Palm Springs International Film Festival Festival (Jan. 5-18) continues to be the place to be seen for foreign film Oscar contenders, 41 of which screened in this year’s Festival. U.S. films, for the most part, take a distant back seat, since most serious American filmmakers don’t want to risk of alienating the Sundance Film Festival, which comes on the heels of Palm Springs and insists on its films being U.S. premieres. While there were a smattering of U.S. indies, the majority would never be confused with Sundance entrees, except for the very fine The Most Dangerous Man in America, the Daniel Ellsberg doc (and likely Oscars favorite) that was my favorite film in the four days I was here. But more on that in a bit. Compared to the hipster flash of Sundance or the frenetic marketplace that is Cannes, PS flies under the radar, close enough to L.A. to preserve an aura of Hollywood glamour, far enough to remain unspoiled by the elitism that can pervade in New York or Venice. With its azure desert skies and well-heeled senior demographic, PS is normally a placid experience. This year, however, controversy intruded on the proceedings, as the festival found itself in the middle of a diplomatic imbroglio. Early last week, the festival’s executive director, Darryl MacDonald, received a call from the Chinese consul in Los Angeles, asking that the festival not show the documentary The Sun Behind The Clouds, about Tibet and the Dalai Lama. “I explained that it was a foreign co-production, not just Tibetan,” MacDonald recalls. “They said, ‘you can’t play this film because it’s not accurate. It purports that Tibet is being suppressed by China – even your own government agrees that Tibet is part of China.” MacDonald was not about to let a foreign country dictate what he could and could not show at his own festival. “I said, this is a question of freedom of expression,” he says. “It’s an artistic event, not a political event.” MacDonald refused to pull the film. Days later, the Chinese filmmakers behind the country’s two PSFF entries, City of Life and Death and Quick Quick Slow, sent regretful emails announcing they were withdrawing their films. “This has never happened at any festival I’ve been a part of,” MacDonald says. An emergency meeting was convened with the consul. MacDonald asked him how he would feel if, say, the Japanese government requested that City of Life and Death – a film about Japanese atrocities committed during their occupation of the Chinese city of Nanking in 1936 – be withdrawn because the Japanese might feel it’s biased. “But that film is the truth!” the consul reportedly exclaimed. “The Tibetan film is full of lies!” The consul also assured MacDonald that it wasn’t the Chinese government that elected to pull its films, but the filmmakers. Uh-huh. And if you believe that, you believe that Mark McGwire took steroids to improve his health, not his strength. To show their support for MacDonald, Sun Behind The Clouds directors Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam flew in from India to be at the festival for the film’s presentation. According to MacDonald, “they found it ironic that the Chinese, who always complain about U.S. interference in their politics, had no hesitation about interfering with a film festival.” On the lighter side, the festival’s annual Black Tie Awards Gala, which honors Hollywood actors from the year’s best films, was highlighted by Mariah Carey’s drunken acceptance speech for Best Breakthrough Performance for her role in Precious. Standing onstage with Precious director Lee Daniels, Carey delivered a loopy five-minute ramble caught in all its glory by TMZ, and viewed by some 1.8 million on YouTube. At least this was something MacDonald could laugh off. “Because this awards show isn’t televised, and takes place outside of Hollywood, it presents an opportunity for talent to let their hair down,” he says. “Anything can happen here.” After the opening night presentation of a proper Oscars contender, The Last Station, the Festival got down to business. With 191 films unspooling from more than 70 countries, and as many as six or seven films showing at a given time from morning till night, the choices are agonizing, and I frequently found myself lamenting films I had missed. (“You didn’t see Airdoll?” a Festival volunteer exclaimed, referring to Japanese director Hirozaku Kore-eda’s film about an inflatable sex doll come to life. “That’s the best film here.”) No, I didn’t see Airdoll. Instead, a critic friend and I kicked off the first day of competition with a jam-packed screening of The White Ribbon, Michael Haneke’s starkly beautiful-but-creepy study of strange goings-ons among the children of a rural German village in the days leading up to World War I. Gorgeously shot in vivid black-and-white by Christian Berger (already cited as Best Cinematography by the New York Film Critics Circle), even the leisurely-paced scenes (of which there are many) seemed cloaked in menace and foreboding. The film resolves few of its narrative mysteries, but chillingly foreshadows the devastation to come once these children grow up to become the adults of 1933-45. I left the film feeling grateful to have not grown up in a strict German household. The Luxembourg/Swiss co-production of Draft Dodgers may conjure up memories of Vietnam, but in fact, is a coming-of-age story about a young engineering student in Nazi-occupied Luxembourg who, rather than be conscripted and sent to the front lines to fight the Allied forces, hides out with a group of “draft dodgers” in the underground mines. The men are suspicious of the student, whose father was a Nazi collaborator. The debut feature from theater director Nicolas Steil, it presents audiences with a “what would you do?” series of moral questions, and examines the qualities that define heroism, and the sacrifices required. Later on, my critic friend rejoined me for the Danish film Terribly Happy. Five minutes into the film, he bolted up in his seat. “I’ve seen this,” he muttered. “I saw it at AFI. You’ll like it,” he said, as he made his way out. “It’s quirky, like the Coen Brothers.” And indeed - it is. The premise is reminiscent of the British film Hot Fuzz, where a cop from the big city (in this case, Copenhagen) is given “punishment” duty in an undesirable province. The similarities end there, however: the Danish town is full of secrets, and outsiders who can’t adapt often disappear, with a nearby bog as evidence. Director Henrik Rubin Genz fashions a nourish dark comedy with overtones of Blood Simple, as the poor cop – who’s hiding a secret of his own – gets inextricably caught up in the town’s corruption and deceit. Saturday morning kicked off with The Most Dangerous Man in America (pictured above), the engrossing story of Daniel Ellbserg’s startling transformation from Pentagon wonk to anti-war activist, after his increasing disillusionment with how the American public was being lied to about what was really happening in Vietnam. (Sound familiar?) It led to a crisis of conscience that resulted in one of the landmark freedom-of-the-press cases in history - Ellsberg’s decision to turn over the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in July 1971. After the film ended, Ellsberg walked out on stage to a standing ovation, and when the first question came about how the film compared to modern-day events, Ellsberg wasted no time venting his unhappiness with the current Administration. “We should be out of Afghanistan,” he pronounced, then went on a spirited analysis of how Lyndon Johnson and Barack Obama were both “smart men leading us into the same dangerous pit when it comes to war.” Opting to end the day on a fluffier note, I went for a French-Canadian buddy-cop comedy from Quebec, Fathers and Guns, that’s already been acquired by Sony for an American remake. Directed by Emile Gaudreault, it’s about the antics of a father-and-son undercover cop team who go on a weekend retreat to entrap the defense lawyer of a notorious biker gang leader, while also working out their (predictably) dysfunctional relationship. I can only hope the Hollywood version will be a lot funnier, but I’m not holding my breath. I wanted very much to like Ajami, an ensemble drama, co-directed by Israeli Yaron Shani and Palestinian Scandar Copti, that’s been likened to a Middle Eastern Crash. The filmmakers talked at length about the challenges of making the film, set inside the Israeli city of Jaffa, at a Talking Pictures seminar on Sunday morning. The film took seven years to make, and was shot with an all-amateur cast that the filmmakers trained for a year, using improvisation and role-playing techniques. They spent 14 months editing 80 hours of footage. According to Shani , it’s the first Israeli film that’s brought Arab audiences into Israeli cinemas. Adds Copti, “It’s a rare chance for Palestinians to see themselves from the outside.” Yet despite their honorable intentions, Ajami falls flat. Like Crash, the film interweaves multiple storylines, and jumps back and forth in time to reveal new perspectives on the same event, forcing audiences to reexamine their own perspectives. But the similarities end there. The film is undone by a tedious middle section in which the story grinds to a halt, and the characters’ motives become unclear. It was almost impossible to distinguish Christian from Muslim from Jew, which, while admirable from a humanist standpoint, proved frustrating when trying to follow the disjointed narrative. What the film lacked in dramatic tension, it more than made up for in the inflammable Q&A after, when several audience members took exception to Copti’s observation that Arabs living inside Israel felt like second-class citizens, and another questioner asked the filmmakers what they “planned to do” to end the cycle of revenge and violence – a question that no one in the Middle East has been able to solve for the past 80 years or so. Finally, there was Transmission, a post-apocalyptic Hungarian film about a world where televisions and computers have stopped working, and a population deprived of its TV and Internet fix slowly descends into chaos. Directed by Roland Vranik, it’s alternately mesmerizing and maddening. It reminded me of those old Budweiser Dry commercials, when a plaintive voiceover asked, “Why are foreign films so… foreign?” There are no easy answers and not every storyline is paid off. It’s told from the point-of-view of three brothers, and the film is at its best when focused on Henrik, a madman/artist who’s had insomnia since losing his beloved TV, and finds an ingenious method to recreate the viewing experience. One form of communication will be replaced by another, Vranik seems to say; if the projector had shut off and the film had stopped in the last reel, I wouldn’t have been the least bit surprised. Heading back to L.A. on I-10, I contemplated what I had seen. I hadn’t been blown away, by any single film, but I’d seen some pretty thought-provoking ones, and had only walked out on one: an incomprehensible Greek movie, Dogtooth, that I’m sure will have its revenge on me when it becomes one of the five Oscar-nominated foreign films. International cinema is alive and well in Palm Springs, and if I didn’t always understand exactly what I’d seen, that was OK too. At least I was still thinking about it the following day, something which happens all too rarely in mainstream Hollywood. Labels: Festivals

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 1/15/2010 10:04:00 AM

Monday, December 7, 2009

HAWAII INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

By Jason Sanders

The 29th edition of the Hawaii International Film Festival (Oct. 15-25) kicked off with its usual blend of sun-kissed island charm and formal glamour; a sunset opening party at the historic Royal Hawaiian Hotel, steps from the beaches of Waikiki, seemed like some stage-managed idea of what “the good life” should be, with tiki lights flickering in the warm breezes, views of a sun setting along the beach, the tinkling of wine glasses, great food, jovial filmmakers, various Lost cast members mingling with Hawaiian artists, mainland stars, Korean producers, Japanese directors, and more. “Only in a place like Hawaii could all these different people come together,” mentioned more than one observer. Unfortunately, another conversation was also taking place, one that echoed a growing uncertainty for many in the Hawaiian film community: after many years of service, the Hawaii Film Office, which assists visiting filmmakers, television crews, and production teams in navigating the island’s physical and bureaucratic landscapes, was facing budget cuts that would leave it either completely shut down or severely limited. [At press time, it was announced that while it would still remain open, only two staff members would retain their jobs.] With over $146 million spent in Hawaii by film and television productions last year (and with even more millions undoubtedly spent by tourists eager to visit the sites they had seen in those films and television shows), the decision to lay off the trained staff who help those productions (and make sure they return) was the main topic of conversation among local audiences and filmmakers. Paradoxically, this year’s festival, led again by main programmer Anderson Le and executive director Chuck Boller, served up possibly its strongest ever line-up of local films, with a successful feature (Marc Forby’s Barbarian Princess, which nabbed the Audience Award and which was discussed on our Festival Ambassador Blog), skillful documentaries (especially Anne Misawa’s State of Aloha; Tom Coffman’s Ninoy and the Rise of People Power, and Marleen Booth’s Pidgin: The Voice of Hawaii), a collection of great shorts (including, but not limited to, Brent Anbe’s Ajumma! Are You Crazy, Kathleen Man’s Lychee Thieves, and Vince Keala Lucero’s Holumua), and even the return of former locals like director Eric Byler (with his accomplished, utterly unnerving documentary on immigration clashes in Virginia, 9500 Liberty) and producer Mynette Louie (here with Tze Chun’s riveting American indie Children of Invention, which won the festival’s Puma Emerging Filmmaker Award). Misawa (the cinematographer of the award-winning Treeless Mountain) teamed with students at the University of Hawaii’s Academy for Creative Media for State of Aloha, a straightforward but well-done look at the history of Hawaii’s fifty years of statehood. Students were given the opportunity to learn from seasoned editors, sound recordists, cinematographers, and tech crews as they worked, creating not only a great documentary film in the process, but hopefully some future documentary filmmakers. No dry history lesson or talking-head monologue, State of Aloha captures not just the history of Hawaii, but the spirit of its people. Marleen Booth’s Pidgin: The Voice of Hawaii also aims its lens straight at the spirit of Hawaii, more specifically at its specific dialect/language/accent, “pidgin.” A blend of Native Hawaiian, English, Chinese, Portuguese, Japanese, and Tagalog that started among plantation workers a century ago, pidgin has been historically frowned upon by those wishing to “assimilate properly.” For many, though, it’s a source of pride and island identity, and Booth’s joyful film is a testament to both it and its just-as-colorful speakers. As a film on the history of language and semantics, Pidgin is a thoughtful, well-researched work; as a film on identity politics, everyday life, and speaking one’s mind (in one’s own tongue), it’s a real pleasure. Neither Pidgin or State of Aloha redefine the documentary form, of course, but both are wonderful examples of how cinema can represent its community. Another pleasure could be found in Brent Anbe’s good-natured comic short Ajumma! Are You Crazy?, whose plot—three star-struck middle-aged women will do anything to meet their favorite Korean soap-opera actor during a film festival appearance—is inspired, in part, by HIFF’s status as the premiere festival for, well, middle-aged women who’ll stop at nothing to meet their favorite Korean soap-opera star. Ajumma’s plus-sized Sex and the City-styled heroines (more Target than Coach, though, and far more appealing), along with its snappy dialogue and underdog pleasures, earned it the Audience Award for Best Short. Not just content highlighting the island’s talents, HIFF continued to solidify its rising status as one of North America’s premiere destinations for Asian cinema. This year the fest screened such much-anticipated works as John Woo’s Red Cliff, Bong Joon-ho’s Korean thriller Mother, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s bizarre fantasy Air Doll, Tsia Ming-liang’s Face, Tony Jaa’s martial arts epic Ong Bak 2, and Yukihiko Tsutsumi’s 20th Century Boys, a sci-fi opus involving schoolboys, end-of-the-world cults, comic books, and, um, T. Rex. Spotlights on Filipino commercial cinema and Okinawan filmmaking saw the fest reaching out to its fellow “islanders,” with Yosuke Nakagawa’s quiet tearjerker Cobalt Blue and Yuji Nakae’s winning tropical-Shakespeare Midsummer’s Okinawan Dream (pictured) among the standouts in the latter section. Attention should also be given to the appealing Honokaa Boy by Japanese director Atsushi Sanada; shot in the sleepy Big Island town of Honokaa and revolving around a listless Japanese teen who befriends the community there, it places the sly observational charm of recent Japanese film in a gorgeous Hawaiian setting, and was one of the top films of the festival. As usual, HIFF also highlighted strong “mainland” American talents, both established and emerging. Reknown Bay Area-based cinematographer Emiko Omori (whose credits include Regret to Inform and The Fall of the I-Hotel, as well as her directorial debut Rabbit in the Moon) returned to HIFF with her portrait of the famed tattoo artist Ed Hardy, Ed Hardy: Tattoo the World. Covering Hardy’s California childhood (where he gave classmates ink tattoos), his tattoo apprenticeships, his breakout as a recognized artist and his current fame as a global tattoo icon, the film moves far beyond the “Ed Hardy Brand” to discover Ed Hardy, the artist, and Hardy, the person; it’s also an amazingly personal portrait of a true American artist and iconoclast. Omori and Hardy have known one another for over 30 years (his San Francisco studio was the basis for her 1980 work, Tattoo City, and she boasts her own Hardy tattoo), and their relationship adds a warmth and depth to the film that’s rare to see. Just beginning his career, the young American filmmaker Aaron Woolfolk brought his debut feature The Harimaya Bridge to HIFF, where it made its North American premiere. Woolfolk used his experiences as an English-language teacher in Japan for this soft-spoken, graceful film, which follows an older African American man as he travels there to unravel the mysteries of his son’s death. More attuned to the rhythms of Naruse or Kinoshita than Scorcese or Spielberg, The Harimaya Bridge is an intriguing surprise from such a young, unknown filmmaker, using simply told moments to capture the beauty of a mountainous Japanese village, or the sorrow of those whose lives cross paths there. Fresh off its award-winning screenings in San Diego, Philadelphia, and Fort Worth, H.P. Mendoza’s San Francisco Mission-district-back-alley musical Fruit Fly delivered a refreshing jolt of attitude to Hawaii audiences. This loud-and-proud, indie/Asian/queer hijacking of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is a worthy follow-up to Mendoza’s Colma: The Musical (co-directed with Rich Wong), following its wide-eyed heroine (L.A. Renigan, a non-Hollywood Holly Golightly for the iPhone era) as she stumbles (and sings) through various drunken nights and hungover days. Fruit Fly represents a new generation of Asian American filmmaking; its deceptively casual mash-up of ethnic and sexual identity politics is nuanced enough to fuel a few master’s thesis, but one doesn’t need a degree to understand the joy on offer. Similar in attitude was Quentin Lee’s The People I’ve Slept With, which made its world premiere here; this romantic comedy involes a young woman whose drunken one-night stands have left her suddenly pregnant, and with a few too many choices as to who, exactly, the daddy is. Thankfully updating the typically bland Hollywood rom-com with some refreshing openness towards female sexuality and an appealing multiracial line-up, the film also boasts a radiant lead duo in Karin Anna Cheung and Archie Kao, who bring a star power and screen presence that not only match, but overshadow, the casts of any current Hollywood romance. Whether big-budget Asian genre films or small-scale American independents, HIFF once again offered many things to many people, but it was the local work that truly shone. Whether intentional or not in terms of addressing the cultural cutbacks, HIFF’s more focused “Island” line-up presented a showcase of the strengths, talents, and hopeful future of the Hawaiian film community; here’s hoping it not only survives the challenges it’s now facing, but thrives. Labels: Festivals

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 12/07/2009 08:33:00 PM

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

By John Magary

Whither primary sources? Here’s what I have in front of me, in case you’re interested: on the desktop sits the laptop, the phone, the book, the headphones. On the laptop’s desktop, the news, the blog, the review, the video, the work. On the phone, the music, the number, the same review as on the laptop, a different source of news, and some text. I’ve got headphones in. I’m tuned in to everything. There’s this feeling that something’s being lost, and so I wonder: what’s everyone else thinking? I cross-check my own opinion with reviewers or reviewer-aggregates, I navigate, looking for commentary or interviews, anything to make the experience more “special,” I call, I comment, I search. I do just about everything but sit in the dark and let the goddamn movie I just saw sink in. The notion of steady work as a paid film critic, the kind of work that existed maybe a few years ago, is officially “quaint.” It’s bad enough out there to make one envy the sick-making whirligig that is the independent film industry for its intrigue and glamour, even if that glamour’s about as convincing as tinsel on a Christmas tree in mid-January. For the young ones, writing on film can only be a hobby, a passion certainly but also an unpaid and under-read time-suck. Press screenings look more and more like carousels for the smart and poor, turning round in the wafting carnival aroma of one more free screening in the morning, one more free cup of coffee, one more chance to dent and be dented. Don’t get me wrong: there are worse ways to spend your time. But that this carousel’s not only turning but sinking is a hard feeling to shake. Forgive the nail-biting, but to a worrywart like myself—a worrywart filmmaker, no less, whose investment in the future of cinema is more than theoretical—it’s hard not to notice that the theaters are getting emptier, the conversations are dwindling, the gap between independent film and studio slop is, incredibly, stretching even wider. Depending on your capacity for optimism, moviegoing’s always typified either a bleak or a romantic kind of dark isolation, the appeal of which is still plenty strong. But the specialness is looking more and more like scariness: we’re so screen-oriented now, dedicating eight to ten hours a day Coming to the Light, that the very notion of The Movies and their attention-demanding primary-ness—long, prickly, character-based, thirty feet high—starts to feel as comforting as boiled Brussels sprouts. “You wanna watch a movie? But I watched three at work!” So there went the 47th New York Film Festival (Sept. 25 - Oct. 11), a hand-picked autumn bushel of primary sources, and it’s all over but the bitching. Unlike some high-profile American festivals who shall go nameless—they rhyme with “Funpants” and “My Schlecka”—the New York Film Festival takes its adult attendees’ seriousness about, um, film, pretty much for granted. There’s blessed little sophomoric reassurance and sloganeering—no buttons admonishing us to “Focus on Film,” no eye-rolling plays on “reel” or “take,” no (or not much) egregious sprocket-hole imagery. A model of sobriety, programmed by genuine lovers of the medium, the festival flatters its attendees with a notable lack of falderal, letting the films more or less speak for themselves. Honestly, this recession-haunted year had almost too little circus: it was the soberest in my short memory, and the least special, with the misguided, head-scratching, depressingly corporate decision by new management to shift the Opening Night party from the lantern-lit, openhearted mazes of Tavern on the Green—with its goofy crusty-mascara charm, the party was a quarter-century-old tradition—to more hushed VIP-friendly digs at the luxuriously renovated Alice Tully Hall. And the outright redaction of the cozy bacon-and-eggs Directors’ Party at O’Neals’ Restaurant? Makes you feel bad for the invited filmmakers, bumping around on Broadway for a true-blue New York shindig. Still, though, reliably awkard question-and-answer sessions, a handful of red carpets, Directors’ Dialogues, a boutique main slate, a life-saving new $10 rush ticket system, and adventurous sidebars: this is a festival whose clarity and respect impresses even the most mole-like of cinephiles. It’s both a glimpse back to a Jurassic Age when films lumbered the earth big and loud, and a glimpse forward to a closer-than-we-want time when “going to the movies” will be thought of as something like an old-timey event, like sledding or making popcorn balls. As happens in every other year of its existence, much has been written this go around about the festival’s “elitism” and penchant for misery, so I won’t bore you with my two cents—and make no mistake, the snobs-versus-populists debate is way past dull. For all the talk of the selection committee’s monocle-and-top-hat rejection of more “open” (read: middling, comforting, fleeting, commercial) fare, I couldn’t help but notice the very healthy and enthusiastic crowds for, to name some, Police, Adjective, Life During Wartime, The White Ribbon, White Material, and Bluebeard, all of which are downbeat, off-tempo, and more or less unkind. Even the screening I attended of Pedro Costa’s numbing/hypnotic and typically uncompromising Diary of a Chanteuse Ne change rien scored a half-full house (before the walkouts): not bad in this economy! Some years are better than others, nobody’s perfect, and so on. (Okay, here’s two cents: Did they miss a few? Maybe, but get over it, will ya?) Whether or not you agree with the slate is beside the point: one might take it on faith that the members of the selection committee—Lion of the Senate Richard Pena, Jim Hoberman, Scott Foundas, Melissa Anderson, and Dennis Lim—are choosing the very best films out there. Still, I found myself questioning my faith, if only a little. I suspect Lincoln Center loyalty (and the promise of a flashy red carpet) may have been an irresistible factor in the inclusion on Closing Night of Pedro Almodóvar’s Broken Embraces, a lollipop-dipped-in-Campari noir celebration of art, love, and, well, Almodóvar. This is Pedro spinning his wheels, tarting up his preening, artsy-Ezsterhas plot mechanics with soapy line readings, pointless self-reference, and heaps of shallow-focus close-ups that will doubtless be described in some quarters as “luscious” or “sumptuous” or some other food word. Also in minor mode, if more intriguingly so, was Jacques Rivette, whose Around a Small Mountain has a disarming vulnerability, but ends up a stitched-together and half-baked experience, its warmed-over themes (life as performance, past as performance) explored with greater perception by the eighty-one year-old director in earlier, better films. By no means painful, but still: consider before you start your Rivette fixation here. At least a decade away from hindsight and with an impaired view—I managed to see only fifteen films from the main slate not including such loud-shouting titles as Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist, Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers, and Alain Resnais’s Wild Grass—I’ll venture to say it was not, alas, a vintage year for the New York Film Festival. Marquee names putting out admirable work with trademarked themes and not much jazz. Compared to last year’s festival, which introduced New Yorkers to A Christmas Tale, The Headless Woman, Summer Hours, and Hunger, there was less to gorge on, less to fight over. Mighty nourishing, but, yeah, thanks, I do have room for dessert. That said, this is a world full of options, and in the interest of air-clearing, let’s just get it over with. Okay: “MISS WITH A CLEAR CONSCIENCE.” All have virtues, but still: Life During Wartime, directed by Todd Solondz. His broad swipes at imponderable selfishness are by now stale (his fault!), and his shot selection is alarmingly uninspired, even amateurish. A funny, provocative, plunked-down debate over the capacity to “forgive or forget” late in the game left me fighting to do the former. Min Ye..., directed by Souleymane Cissé. As with Life During Wartime, a by-now-veteran loses control of the frame. Loads of Guiding Light-style close-ups and unshaped squabbles are almost redeemed by an off-kilter, very funny central performance by Sokona Gakou. Unfortunately, rounding the thing off at a woefully bloated 135 minutes, Cissé has done his best to shoot himself in the foot. Precious: Based on the Novel Push by Sapphire, directed by Lee Daniels. What’s with the title? Did someone lose a bet with Sapphire? Propelled by social issues, dreams, and overwrought Gloom, this is a grab bag about perseverance, and finally, backflipping redemption. Visually, Daniels enters each scene like he forgot the last, but there’s no getting around the dedication of his performers. It’s a little much to see a Harlem social worker drop a tear at her desk, but still, that was Mariah Carey, and I barely recognized her, I actually bought her, and that’s some kind of trick. “YEAH. IT WAS GOOD. I MEAN...YES. YES, IT…I LIKED IT.” Like the American Southwest, this territory comes with a certain number of reservations: Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl (pictured), directed by Manoel de Oliveira. How old is Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira, really? I heard he punched Thomas Edison in the face once for showing up late to set. Someone else told me he was seven when The Birth of a Nation came out. Can either rumor possibly be true? In any case, his sixty-four minute cut glass perfume bottle of a film feels like it was carefully transported, in a velvety pouch, from a different age. I wouldn’t say it compares so favorably to late-era Buñuel, but Oliveira’s visual scheme, falling somewhere between drab and fancy, is odd, refreshing, even exhilarating. I hope that when I’m 101 I’ll remember the film’s stunning last frame: the titular object of desire, seated, her legs open, her head down, beast-like, slipped off. The White Ribbon, directed by Michael Haneke. By now, Haneke has amassed quite the flock of hairshirted admirers, and until I got to the end of this long and scolding communal mystery, I counted myself unquestionably among them. Startlingly precise imagery in the service of…what, exactly? Haneke has left out the answer to his own painstaking equation; the love story at the center is tender and honest, but the moral ugliness swirling around it feels like Halloween decoration. He’d be easier to shake if he weren’t so goddamned talented. Ne change rien, directed by Pedro Costa. If I’d walked out on this, would it have ceased to exist? Costa, a hardcore formalist and unapologetic descendant of Straub/Huillet and late-era Godard, chronicles the actress-turned-chanteuse Jeanne Balibar, as she, well, tries to get the beat right. Like his countryman Oliveira, Costa knows exactly where to put the camera—far but close—and relishes limitation, but your engagement might rely not on his placement, but hers. Forgive me for this, but is Balibar any good? Is she worth all this? In any case, Costa’s getting the Eclipse treatment soon from Criterion, and I can’t wait to wait. Police, Adjective, directed by Corneliu Porumboiu. Hard not to envy the young Romanians. The continuity in their collected work—from The Death of Mr. Lazarescu to 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days... to this one—is astounding. Just about guilty of art-film collusion, or an excess of bone-dry orthodoxy, the directors share a deep respect for quotidian timeframes and the ways in which bureaucracies degrade us all. Porumboiu’s new film is, in parts, genuinely funny, and in other parts, needlessly patient. There’s a good idea here, however drummed through, that language hides as much as it exposes, but too much effort is spent toward what is by now a stone-cold festival cliché: torturing the audience for the sins of the state. “90% OF MY LOVE.” Masterpieces? Maybe none of them. But they deserve your $12: White Material, directed by Claire Denis. One of the few films at the Festival without a reliable agenda, and one of the very, very few to express itself through rhythm. I was enchanted by the movie-movieness, the assured fusion of color, sound, composition, and performance. Denis’s characters are puzzling—does she lack confidence in language itself, or just her own dialogue?—but their convictions are never less than razor-sharp. Even with the willfully wackadoodle ending, this French-colonial action movie threw me into a pleasure-tizzy. The image of boy soldiers, scattered at rest, picking pills from the dirt—at once horrifying, sensual, alien, rapturous—is locked away in my noodle for good. Mother, directed by Bong Joon-ho. The impressive, cloying opening shot—a lilting crane floats down to a sad middle-aged woman, as she starts to dance—had me worried. But in the end, it’s Joon-ho’s honking imagination that makes this convoluted whodunit hum. A master of tone and point-of-view, Joon-ho guides his audience through one convoluted scene after another toward a remarkably humane portrait. A structural tour-de-force, and appealingly whimsical: if things were right in the world, Joon-ho would be a household name here. Bluebeard, directed by Catherine Breillat. Speaking of getting things right, could someone please throw Breillat a budget? A little shabby in design—unnecessarily lame video photography and unconscionably lame costuming—this feminist reexamination of the grisly Charles Perrault bedtime story is nevertheless a cold-filtered beauty. Contemporary to her core, Breillat teases out yearnings and dynamics that Perrault never dreamed of, and stamps the story with her own darkly funny, achingly proper moral. Ogres have rarely been so appealing. “I DARE YOU NOT TO LOVE THIS MOVIE, FRIEND.” Heaven can’t wait for this lone angel: Everyone Else, directed by Maren Ade. As someone who makes his living (or “living”) as a filmmaker, I’ll cop to an often foggy POV, and a complicated relationship with new cinema. Like many of my filmmaker friends, I’m bringing baggage into the theater with me—that day’s unfinished writing, the call unanswered, and, hardest to shake, the diamonds-and-granite conviction that, when all is said and done, movies should be made my way. (Oh, and there’s some jealousy.) Maren Ade, young, on only her second feature, has made a deceptively straightforward, plainly episodic portrait of a couple slowly unraveling. And the film gets so many tiny things right, it gives me palpitations. This isn’t an expressive work, really; her mise-en-scene blazes no trails. But how many directors—Pialat? Cassevettes?—have so convincingly tracked the minute directions of the human heart, so brilliantly modulated the tiny fears of an on-screen couple (Birgit Minichmayr and Lars Eidinger)? Never less than uncanny, adroitly avoiding the pitfalls of squishy romanticism and arty mopiness, Ade’s film cashes Mumblecore’s check. The scenes fall like dominoes, until we’re left screaming for our loved ones. This is a primary experience. What will Maren Ade do next? Can she keep it up? Who knows? I’m too excited to worry. Labels: Festivals

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 10/14/2009 11:35:00 AM

Saturday, September 26, 2009

VENICE FILM FESTIVAL

By Belle N. Burke

While construction of a new Palazzo del Cinema is under way in the center of the film festival venue, causing some dislocation and confusion, Venice's 66th edition (Sept. 2 - Sept. 12) produced a festival it can be proud of, diversified enough to offer something of quality for everyone but catering to no one. Among 75 official selections from 25 countries (the largest number in Venice's history) featuring 71 world premieres, there is a deliberate mix of what Marco Muller, the festival director, calls highbrow and popular art. Films that pleased, offended, or were remakes of previous films engendered debate and emotional reactions, which is what I believe a film festival should do. The official sections included Venezia 66, whose jury, headed by Ang Lee, awarded the Golden Lion for Best Film to Lebanon, based on Israel's invasion of that country in 1982, in which the director, Samuel Maoz, participated as a young soldier, and for the past 20 years has been trying to come to terms with the experience. He is the third Israeli director to deal with the horrors of that war, after Ari Folman ( Waltz with Bashir) and Joseph Cedar ( Beaufort), and can expect a mixed reception in Israel. Six U.S. films competed for the prestigious Golden Lion, among them Michael Moore's Capitalism: A Love Story and Oliver Stone's South of the Border. As disparate as they appear, there were perhaps inevitable comparisons, e.g., two American documentaries exposing the flaws of capitalism, Moore's receiving clamorous applause for its content and courage while Stone's became a media event as Hugo Chavez appeared on the red carpet (just another celebrity?), smiling, waving, and signing autographs. The press and the public were out in force in a surreal scene (think Fidel Castro at a film festival!) as Chavez basked in an incalculable amount of free publicity. Orchestrated by Stone, who insists that Chavez is misunderstood and unjustly criticized in the U.S., ignoring his decision to remove term limits on his presidency and other annoying facts that didn't fit his script, the film also includes six other South American presidents of countries that do not always qualify as democracies. Although strong performances mentioned for best actor included Matt Damon in Steven Soderbergh's The Informant!; Nicholas Cage in Werner Herzog's Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans; and Viggo Mortensen in John Hillcoat's The Road, the Coppa Volpi went to Colin Firth in Tom Ford's A Single Man. (Herzog is the first director ever to have two films at the same Venice festival; the second was a "surprise film," My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?, which almost nobody liked. He seems to have an ongoing feud with Abel Ferrara, whose 1992 film with a similar title starred Harvey Keitel, and who was also present with a new film, Napoli Napoli, Napoli, not in competition). The Silver Lion for Best Director went to Shirin Neshat, an Iranian artist/filmmaker, for Women Without Men; the Special Jury Prize went to Soul Kitchen (an audience favorite) by Fatih Akin, a second-generation Turk who lives in Germany and until now made darker films such as Head On, the 2004 Berlin Golden Bear winner and The Edge of Heaven, best screenplay at Cannes in 2007; Ksenia Rappoport for Best Actress in La Doppia Ora, directed by Giuseppe Capotondi; the Marcello Mastraoianni Award for Best Young Actor or Actress to Jasmine Trinca in Il Grande Sogno by Michele Placido. Todd Solondz won Best Screenplay for Life During Wartime; Sylvie Olivé for Best Production Design in Mr. Nobody; Lion of the Future for a Debut Film went to Engkwentro by Pepe Diokno in the Orizzonti section; the Controcampo Italiano Prize went to Cosmonauta by Susanna Nicchiarelli; and Special Mention went to Negli Occhi by Daniele Anzellotti and Francesco Del Grosso. Among the films that stayed in my mind: Goran Paskaljevic's Honeymoons on the open wound of immigration; Io sono l'amore by Luca Guadagnino, memorable mostly for Tilda Swinton; and Yonfan's Prince of Tears about Taiwan's "white terror" in the 1950s. Baaria, Giuseppe Tornatore's meticulous recreation of his childhood in Sicily and the first Italian film to open a festival here, was preceded by high expectations but failed to impress. This was an exceptional festival that reflected not only the superior quality of number of films, but also the fact that there is no more "Hollywood," a never-never land where all the makeup was perfect and reality was often shown the door. Once that door was opened it can never be closed, and Venice this year did not shy away from politics-both good and bad-and demonstrated the democratization of cinema. By welcoming filmmakers and actors of all ages, nationalities, ethnicity and sexual orientation. But tradition and familiar faces are still welcome: Omar Sharif did a tour de force turn in The Traveler, Sylvester Stallone was given a Glory to the Filmmaker award, and to provide continuity, George Clooney, a perennial idol in Venice, arrived this year with a new film, The Men Who Stare at Goats, and a new fiancée-Italian, of course. The festival itself could have been a film script, I kept thinking, with improbable celebrities eliciting unexpected enthusiasm, and healthy disrespect for the politicans and institutions that deserve it. For example, Videocracy, a documentary by Italian Erik Gandini, shown in Critics' Week after it was canceled as an official entry and its ads removed from the leading TV outlets, targets Berlusconi's stranglehold on the media. Francesca, a film by Romanian Bobby Paunescu on racism in Italy, contained unfortunate quotes about Romanians in Italy by both Alessandra Mussolini (a member of the government) and the mayor of Verona, and was withdrawn from the festival after strong objections from the government despite its warm reception. Having expressed my admiration for Venice 66, I must add that I have seen the most extraordinary fusion imaginable of art and film in Peter Greenaway's The Wedding At Cana ongoing project that will eventually illuminate nine great paintings, a surprise screening that I saw twice. Labels: Festivals

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 9/26/2009 10:16:00 PM

Saturday, August 8, 2009

THE DUBAI INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

By Scott Macaulay

Now in its fifth year, the Dubai International Film Festival stands at an uncertain but nonetheless exciting crossroads in the international film scene. In the last several years, the Middle East, particularly the United Arab Emirates, has been a source of financing for both studio and independent organizations ranging from Warner Brothers to Participant to Sundance to National Geographic. As the real estate and finance bubble accelerated in recent years, Dubai, known for both, became also a synonym for outsized opulence, glitz and glamour. However, as the “office space for rent” and stalled construction projects spotted during the car ride from the airport at this year’s fest revealed, Dubai has been hit by the global downturn just like everywhere else. Perhaps appropriately, then, the 2008 Dubai International Film Festival (December 11 - 18) didn’t completely coincide with my expectations. (For the record, I traveled there as a guest of the festival.) Yes, there were incredible accommodations, stars (Salma Hayek, Goldie Hawn, Ben Affleck and, to introduce producer Charles Roven, who received the Outstanding Filmmaker of the Year Award, Nicolas Cage), and lavish events, but there were also serious discussions about the region’s role in international production made even more urgent by the global economic disruption. Commented Nadia Saah, partner in BoomGen Studios, which provides niche marketing, publicity and strategy services for Arab films in the U.S. market, “There are more people this year, and there is a higher level of engagement. In terms of the business side, there is less celebrity flash. It is more substantive, and the industry office here is working really hard to make that possible.” I spent most of my four days at Dubai at industry events, and, for once, the musty back-and-forth that I associate with film festival panel discussions was nowhere to be found. Instead, the very real questions involving “capacity growth” (i.e., new theaters in the Middle East, audience development, and production) and the responsibility of local investors to the region’s artists and audiences were hotly debated in panels like one titled “Who is Holding the Purse Strings?” Walt Disney Studio’s Michael Andreen stated that the region was “one film away” from a crossover hit that would bridge its film community to international audiences while Bahrain-based Sherezade Film Development’s Steffen Aumueller discussed his strategy of raising money in the region for Western films like Smart People and New York, I Love You by comparing for his investors the world of film financing to real estate deals. Similarly, U.S./UAE Serafina Films’s ubiquitous Susanne Bonet stressed her experience developing sound screenplays and explained how she’d apply those skills to the movies she’s intending to make in the region. But during the Q&A, one audience member jumped up to argue that “developed stories” was code for censorship as it automatically ruled out work that would challenge the region’s tastes while another bemoaned the lack of the local financiers themselves on the panel. (A behind-closed-doors session, moderated by Colin Brown, actually did introduce a number of the region’s financiers to the attending Hollywood community.) On another panel, Jordan-based Laith Al-Majali, who produced Captain Abu Raed, which won the World Cinema Prize at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival, described the local filmmaking situation thusly: “Arab moviegoers prefer English-speaking films or commercial Egyptian film. They don’t know Arab independent films exist. Arabs can sustain a Las Vegas but cannot sustain a cinema.”  Developing an Arab cinema is a goal of the Dubai Film Connection. The Dubai Film Connection is DIFF’s CineMart-like financing market, which this year included Cherien Dabis’s Amreeka ( pictured below) as a work-in-progress seeking finishing funds and Filmmaker “25 New Faces” director Annemarie Jacir’s Jordan-set period drama, When I Saw You. Says Lucas Rosant, a consultant and member of its selection committee, “The Middle East is one of the only places in the world where they are still opening theaters. The positive effect of the financial crisis here is that investors realize that cinema is crisis-proof. People need entertainment, and you can still make money. And they realize to do that they need to develop talent. This year for the first time we got sponsors from Bahrain and Kuwait who are looking for Arab content for theaters, TV and DVD. Even Disney is now investing in the production and development of films in Arabic.” Backing up his words, Rosant notes that of the 15 projects in last year’s inaugural Dubai Film Connection, seven have already been shot. “A 50% success rate? That’s great. It means something is really happening here. Dabis commented, “This is my third year at Dubai. My first year I was here for a short film, which won an award that enabled me to continue working on the feature. I came back to the Dubai Film Connection the next year with Amreeka and had a series of meetings. We won an award at the market, and we closed our Middle Eastern presales.” Confirms Amreeka producer Christina Piovesan, about 10% of the film’s $2.5 million budget came from Showtime Arabia (pay TV) and Ratana Studios (free TV and theatrical) — the first time these entities got involved in international production. Other memorable conversations: a panel on cultural exchange moderated by Cameron Bailey with filmmakers Haile Gerima and Deepa Mehta. It turned into an extended dicussion on Barack Obama and his ability to deliver global change, with an optimistic Jeffrey Wright, in Dubai with both W. and Cadillac Records, debating Gerima (who saw Obama as representing the end of the idea of “transformational mobility”) from the audience. Among the American indie filmmakers who attended with their films were producer Alex Orlovsky ( Momma’s Man), director Nina Paley ( Sita Sings the Blues) and actor Michael J. Smith ( Ballast). So Yong Kim’s Treeless Mountain ( pictured at bottom) won Best Film in Dubai’s Asia/Africa Competition while Lyes Salem’s Masquerades ( pictured at top) won top honors in the Arab Muhr Competition. (An edited version of this report appeared in the Spring, 2009 edition of Filmmaker .)Labels: Festivals

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 8/08/2009 02:23:00 PM

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

INDIELISBOA FILM FESTIVAL

By Jason Sanders

The Mozambican Portuguese poet Virgilio de Lemos once wrote that the city of Lisbon “sees itself as an unfinished, incomplete city, open to metamorphoses…open to the delirious imagination of its lovers.” Imagine those ideals in a film festival, and one would have as good a way as any to describe the charm of Lisbon’s new IndieLisboa Film Festival (April 23 - May 3). Celebrating just its sixth edition this past April, IndieLisboa may indeed be young and a bit unfinished, but that’s all part of the appeal; compared to the rather bloated excesses of its European brethren like Cannes, Berlin, or Venice, this festival is intimate, quiet, open to metamorphoses, and, above all, open to the delirious imagination of film (and its lovers). Like Lisbon itself, it rewards those who enjoy traveling off the beaten path, revealing its charms not to those who rush, but those who linger. Whereas most other European festivals trot out the same excessive lineup of tried-and-true, auteur-or-star-driven titles that were in the last festival (it’s a vaguely hidden secret that many festival films just flitter blandly from one city to the next, like some fashionable H.M.V. seasonal outfit), IndieLisboa aims to have a thematic mission. For this festival, the “indie” in its name is not some marketing copy, but the integral reason for its existence. To quote the programmers Miguel Valverde, Nuno Sena, and Rui Pereira, the focus is on “an original and demanding film program... dedicated to discovering and sharing the best in new cinema through the world.” No Holllywood-lite “independent” works, cross-nationalized Europudding, or big-budget Asian genre films here, just a tight focus of around 60 features from around the world, and a deepening concern for the best in new Portuguese cinema. In addition to the competition works, there were strands dedicated to documentaries, emerging cinema, music films (“IndieMusic”), films on filmmaking (the “Director’s Cut” section), children’s and young adult films (“IndieJunior”), and retrospectives of two “intransigently non-conformist and individualist” directors, Werner Herzog and Jacques Nolot (surprisingly, neither one had had full retrospectives before in Portugal). The festival’s knack for assembling a cohesive, effective program was especially pronounced in their selection of American titles. Last year's award-winning success of Azazel Jacob's Momma's Man highlighted IndieLisboa’s status as a rewarding new avenue for emerging American independent film. This year they solidified that relationship, with a program that reads like a who's who of current U.S. indies, including Lance Hammer's Ballast and Sean Baker's Prince of Broadway (both in competition), as well as Barry Jenkin's Medicine For Melancholy, Josh Safdie's The Pleasure of Being Robbed, and Kelly Reichardt's Wendy and Lucy. ( Ballast, Medicine and Wendy & Lucy have all been written of extensively in Filmmaker). A film on a thief, rootlessness, and the simple pleasures of not knowing whether to speak to someone, or steal from them, The Pleasure of Being Robbed gained notoriety last year for being the only American feature chosen for Cannes’ prestigious Directors Fortnight section (Safdie’s newest, Go Get Some Rosemary, featured in Cannes this year). Like his purse-snatching, ever-drifting heroine, Safdie knows that success is in sleight-of-hand and constant motion, and so his vision of cinema is filled with magic and movement, of fragile, seemingly spontaneous moments that surprise at every turn. The film’s 16mm images lend it a warmth and texture missing in digital video, while its structure is as deceivingly simple as the Thelonius Monk tune that frames its soundtrack. It’s no surprise that The Pleasure of Being Robbed was chosen for Cannes; this sweet-natured ramble invokes Celine and Julie, Rivette and Eustache, and others for whom cinema, like making polar bears appear in Central Park, is magic. If Pleasures takes it cues from Rivette or Eustache, Sean Baker’s Prince of Broadway (pictured above) takes its own from the street-level immediacy of the Dardennes Brothers and the baroquely verbalized New York City landscapes of Taxi Driver-era Martin Scorcese. Following a Ghanian immigrant-turned-Garment District-hustler as he deals with knock-off sneakers, uncertain customers, random hoodlums, and a little boy who may or may not be his son, Prince of Broadway captures the movements, aesthetics, and verbiage of life in one substrata of New York City, circa 2008, with utter precision. Along with his earlier film Take Out (co-directed with Shih-Ching Tsou), Baker is creating a visual history of New York City that will one day stand with Scorcese’s efforts; Baker’s, however, will be recognized as far more immediate, and far more realistic. Few American filmmakers today are able to use the on-the-fly freedom of the digital aesthetic—skeletal crew, little equipment, improvisational filming—to capture the way people live, move, and talk today better than Baker. Mixing a fictionalized plot with a very real situation—the lives of Chinese restaurant workers in Take Out, or marginalized African immigrants in the city’s hustler underground in Prince of Broadway — Baker is developing an aesthetic that’s as vibrant as the Dardennes, but with a New York City roughness all his own. Baker was one of the few American filmmakers able to attend IndieLisboa, a shame considering the real hospitality of the festival staff and the relaxed vibe of the entire event. No power lunches or industry-only screenings here; instead, filmmakers had the space and time to mingle with one another, and to respond to audience hungry for new filmmaking. “It was encouraging to see how enthusiastic the audiences are for indie film,” Baker noted. “I wish the US audiences were as hungry for hard to find indies as the Portuguese are.” The festival’s relatively small layout—around 4-5 screening venues scattered around this highly walkable, tree-lined city, each easily accessible by metro or a festival mini-bus—made running into fellow guests simple; mornings found many attendees sharing coffee and brunch at the festival hotel, while late nights found them congregated at the festival’s “official” gathering spot, the notorious nightclub Cabaret Maxine, a former brothel turned atmospheric bar and music showcase. A chance to sample Lisbon’s venues and former brothels wasn’t the only insight into Portuguese culture the festival offered, of course; thanks to the indefatigable Manoel de Oliveira, the sphinx-like Pedro Costa, and the youthful Miguel Gomes, Portuguese cinema is currently one of the most vibrant cinemas in Europe. Possibly Portuguese cinema's most famous name, Manoel de Oliveira (now over 100 years old) debuted his newest film, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, at the festival, but it's some of the lesser-known directors that made an even more intriguing impression. Ivo M. Ferreira unlocked the emotional scars of the 1974 Portuguese Revolution in his family drama/road trip work April Showers, which followed a young man's search through the dry Alentejo and coastal Algarve regions for the mystery behind his father's disappearance. Joao Rosas' experimental documentary Birth of a City combined visual snapshots of London with the story of an artist literally painting a similar portrait of city; its uniting of cinema, painting, and poetic voice-overs refreshingly avoided heavy-handedness for a pleasing, memorable lightness. In Ruinas (Ruins), by Manuel Mozos, there's a different kind of city landscape: it's a documentary on ruined buildings, with Mozos training his camera on abandoned homes, deserted hospitals, and crumbling estates like von Sternberg trained his camera on Dietrich. Epic long takes allow viewers to appreciate the sheer beauty of decay (it's a powerful film to see in Lisbon, home of countless similar old ruins), while narrators accompany the images with texts from various centuries, all recounting obituaries, sicknesses, loves lost, even hotel accommodation requests. Produced by the same group behind Miguel Gomes' Our Beloved Month of August (one of the best new Portuguese films of the year, and one whose off-the-cuff traveling aesthetic should stand as an example to all American independent filmmakers, too), Ruins has a quiet visual poetry similar to the landscape cinema of James Benning, only fleshed out with a saudade-fueled sorrow that seems to ooze from the Portuguese setting. Mozos’ camera lingers on each devastated home, every broken window or crumbling wall; here the setting becomes emotion, with each static take revealing the movement (or stasis) of history, the poetry of loss. It’s no coincidence that Ruins won the Best Portuguese Feature Film Award at the festival, while Lance Hammer’s Ballast won the prestigious Feature Film Grand Prize (and its suitcase full of 15,000 Euros). While literally worlds apart, both films are fueled with this poetry of loss; filled with ruins, landscapes or individuals seemingly caught between collapsing or rising, each embrace the unfinished, the unpolished. It’s a type of cinema that, like IndieLisboa, and this city, rewards those who linger, and revel in the unknown. Labels: Festivals

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 6/09/2009 11:31:00 AM

|

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →