Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation: Unpaid Crew Vs. Under-Paid Crew

In our last post Anna Rebek briefly touched on one very important aspect of sacrifice when it comes to making microbudget films…crew. I think we often have to get past the feeling of incredible guilt in pre-production when asking friends and family to come along on yet another microbudget adventure. However, we learn to compensate with understanding, attention and compassion, making micro budget a unique testing ground for new methods. No matter what happens after these films are made, we are left with lessons that some big-budget filmmakers have never had to learn. Perhaps instead of wondering when to give up, we should be taking this time learning how to prepare for the future. Layton Matthews is here to discuss the merits of treating your crew right…and while you’re at it, why not pay them something.

Let’s say you have written a script and decided to make a micro-budget feature film. You’ve borrowed or rented a camera, locations, microphones, sound recorders, costumes, etc. Maybe you’ve also borrowed or rented a crew. Sometimes your entire budget consists not of money, but borrowed equipment, places and even people.

In a recent post on the Filmmaker blog, Scott Macaulay quotes Michael Polish of the Polish Brothers in reference to their “no-budget” film For Lovers Only: “There was not one dime that came out of our pocket specifically for this movie — besides the food we ate, but we had to eat anyway.” For a lot of filmmakers the cost of rent on their apartments, locations and everyday expenditures like electricity, gas, clothing, their girlfriends’ make-up kits, etc. is their budget. So clearly, there is a budget and then there is a ‘budget.” One could say that the difference between the two is the difference between micro-budget and low-budget filmmaking. It is the difference between an “un-paid” crew and an “under–paid” crew.

It’s amazing how much of a difference even $50/day will make to some of us. Just knowing we’re not working for free goes a long way in making us more likely to give our best effort to some poor, inexperienced, yet passionate filmmaker. But someone may ask, “Is $50/day versus no pay really that big of a difference?” Or, “Is that seemingly small difference in budget, or lack thereof, really what defines my micro-budget film?” No, it isn’t. It’s what you replace it with that defines your micro-budget film.

Today, in a contemporary art gallery you can hang a picture painted with ketchup and mustard of Donald Duck on a piece of cardboard next to a classic oil canvas of a 14th century serf toiling in a field, and no one will blink an eye. However, often in the independent film world, if you are painting with ketchup and mustard you had better not tell anyone until after you’ve sold the painting lest you be labeled an amateur and not sell it at all. In the film world, people often seem to have what they expect a film to be, and tricking them to believe your cardboard is canvas is vital to them allowing your story a chance. To allow their mind to even receive your story unbiased they need to be comforted by the feeling that they are watching a “real movie” before judging it prematurely. For example, “Mumblecore” filmmakers experienced backlash by many, including myself at times, because it was perceived as attempting a “short cut.” However, those that practice it I’m sure would tell you that they are challenging the conventions of how we are taught that art should look or be approached. Like the necessary Catch-22 that is the freedom of speech, so is the subjectivity of art and its processes.

That duality is necessary for the back and forth, the stirring of the pot to keep things in motion and not stagnating. Yet that motivation can only be the means and not the end. There has to be something more important behind it than just challenging the way things are done. Bravery for the sake of bravery is not brave, it’s vanity.

So when we make a micro-budget film, we often have to do everything behind the curtain differently than other films but with hopes that everything on stage appears to be as everyone expected. We try to fill in the gaps left by the money we don’t have. We know we had better fill it with something better than ketchup and mustard. Something as good as red paint like the bigger films have, if not better. Blood? No, that’s too dark. Add some tears and sweat? Better. Add a dash of heart and desperation and you got it. Arriving at what you could call the “Bowfinger Factor.” Many smart people before us have called this phenomenon “Art from Adversity.” It’s a good phrase, except for that it can mean almost anything. The plight of a micro-budget film quickly becomes a very specific one and one that requires the love, passion, heart and work ethic of an emotionally invested crew to keep the engines running when the gas has run out and so has the money. When a large movie can attain this, it’s un-freaking-stoppable. But it’s not an advantage for a successful micro-budget film. It’s a necessity.

The bottom line is that with a good budget you do not need P.A.s, grips, gaffers, or even A.D.s or D.P.s to like, or even have read, your script. You can get them to help you just as if it’s a school-less summer day and you’re all friends in the same neighborhood with a common project, as long as you pay them. They will show up, lend you their various expertise, and be valuable parts of your process. They may not care how well your film turns out, or read the script entirely, but they will be trustworthy to show up, be on time, and unlikely to randomly ditch or call in sick. Money obligates people to care about things they normally would not. Like another person’s artistic/business/sexual/religious/political pursuits. It has always been this way. Reliable help in some basic level of experience is always $50 away. But what if you don’t have the means to even pay a crew that much? What if you don’t have a $100-500K budget that allows you to offer a crew $50-$100 per day like you’d prefer? Plus, you are no longer 14 years old on summer break and your friends and neighbors actually have lives and jobs of their own. How do you get them to help you then if you cannot pay for a crew? How will you make them care?

This dilemma is a line that not only helps us define the difference between micro-budget and low-budget, but it’s also a line that on either side of which lie many differences in how a filmmaker must go about getting his production done well and on time.

I have had the blessing of being a part of indie feature films where I only wore the hat of lead actor as well as at other times the hat of writer/actor, or even as writer/director, which has allowed me the rare chance to observe intimately the many methods of other directors besides myself. I have worked on some films where the crew are paid $500/day and others where the crew made $50/day. The difference between those two categories (in regards to attitude, work ethic, respect for the project, etc) is smaller than the difference between $50/day and $0/day. This shouldn’t be surprising to most of you and I’m not pointing this out to blow any minds. However, that also means that the difference between $100M studio films and $1M low-budget films is smaller than the difference between $500K low-budget and $50k micro-budget films. That’s how unique micro-budget film is, and how unique the methodology of your micro-budget film has to be.

In my humble opinion, making a micro-budget film is a vital experience to a filmmaker because it forces him to gain unique skills of diplomacy different from the average “paid-crew” experience, and always to be more in touch with how the crew feels, and to carry respect for them as fellow artists while they’re all trying to support his vision. Especially when they have a vision of their own and likely do not aspire to be grips or boom ops, but directors themselves.

The biggest difference between low-budget and full SAG multi-million dollar film crews is experience, whereas the difference between micro-budget and low-budget is the necessity of passion from a crew who want to be working. Again, not that it’s not there in the bigger films, just that it’s not as directly tied to the films ability to exist in the first place and be completed. And when you do not have even $50/day, much less $500/day to pay them, you had better find other ways to make them happy to work. You may expect me now to itemize a list for you, the things a filmmaker should do to keep a $0/day crew happy, but I cannot. It’s unique to all micro-budget films. The symbiosis of different but like-minded people and the synergy maintained from a common attitude towards the work is dependent on too many variables. But after learning for each of your film’s what it takes, if you are lucky, you’ll move on to bigger films in the future, retaining those experiences and having stronger and more productively creative relationships with your future well-paid crew as a result. That’s the hope for all of us I’d think.

Now, just because we are further defining “micro-budget filmmaking” with this conversation, doesn’t mean we are inventing it. We can’t forget that the first film ever made was micro-budget. This isn’t a new thing, it is our deepest roots. Discovery of the unknown, experimentation, and the bravery to make mistakes for the sake of possibility are the job of all artists, and most certainly micro-budget filmmakers. To make and test drive the molds in our willful passionate laboratories that the studios take and mass produce, which in turn inspires us to keep moving and never linger on one good idea too long. There is no grand statement or end to this discussion, only a love letter to an art form that will live forever because it needs nothing but willful creativity to be explored and stirred. – Layton Matthews

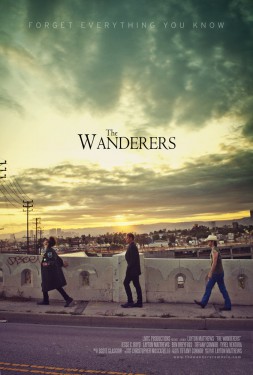

Layton Matthews has acted in numerous films and written/directed 2 micro-budget feature films, the most recent of which is “The Wanderers” (pictured above). Please check out the website and trailer @ (www.thewanderersmovie.com) or on imdb.com.

In past posts we’ve talked about the function of microbudget filmmaking, and whether or not it’s a destination, or a stepping stone. In either case I believe it’s a necessity for up and coming directors. How well are you going to connect with your crew and cast in a low budget indie, if you can’t even handle a microbudget film. Surrounding yourself with a family of filmmakers and collaborators, and learning how to treat them right is not only one of the most important elements to a successful film, It’s the main ingredient to a successful life. This “family”, this connection with your co-conspirators, is also one of the best reasons to make microbudget films if you ask me.

Check out the film of Microbudget Conversation alumni Neal Dhand next Thursday and Friday in Manhattan. Second Story Man will play at the Millennium Film Workshop, 66 East 4th St. on 9/22 and 9/23 at 8pm, with a Q&A following the 9/23 show. There will also be a 3pm show on 9/25.

Neal let me take a look at the film earlier this month and you totally need to check it out. Congrats Neal on a great film and screening!

We’d never turn down the chance to hear from you, especially microbudget fans and filmmakers. To become part of the conversation please send us your thoughts, responses, and questions.