Back to selection

Back to selection

H2N Pick of the Week

Weekly reviews from our friends at Hammer to Nail by Hammer to Nail Staff

Nebraska — A Hammer to Nail Review

Nebraska

Nebraska (Nebraska world premiered in competition at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, where Bruce Dern took home the Best Actor prize. Distributed by Paramount Vantage, it opens theatrically on Friday, November 15th. Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

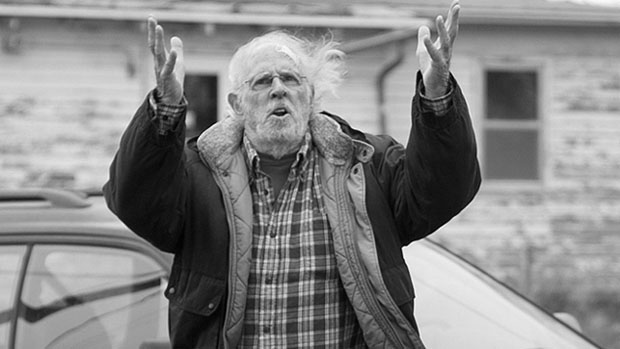

After seeing Nebraska at this year’s New York Film Festival, I struggled to articulate what about it I found so moving. For days after the screening I could picture it in my mind’s eye: those hard, bright Midwestern landscapes in silver and black. With previous Alexander Payne films what I remembered was dialogue, barbed explorations of character. Literary stuff. But with Nebraska, the things that impressed themselves on my memory were largely inarticulate: lighting and composition, performance. And Bruce Dern himself, whose character barely speaks but who nonetheless conveys a whole language of physical expression. This is a director’s film, rather than a film critic’s film. I didn’t want to dissect Nebraska even if I could sense the underlying intelligence at work. It was primarily an emotional experience, and I wanted it to remain that way.

That’s not to say that on the level of craft there isn’t a lot to admire. But with the sophisticated cinematography that’s now possible even with lower budgets, for me there is a reflexive pleasure in seeing a director really carve out a style through their work with actors. In Nebraska, the cast is uniformly strong. Dern plays Woody Grant, the ailing patriarch of a loosely held family, and June Squibb plays his shrewish wife Kate (familiar as the short-lived wife of Jack Nicholson in Payne’s About Schmidt). For the roles of their two sons, Payne mined television talent: former SNL cast member Will Forte in a melancholy turn as their son David, and Breaking Bad lawyer Bob Odenkirk as his decidedly un-Saul-ish brother Ross. Both are notably cast against type. Smaller roles are played by local and non-actors, as aptly chosen as the locations — the farmhouses, bars, and country roads where the film’s quiet drama plays out.

The plot is minimal but immediate, set into motion from the opening scene in which Woody trudges stubbornly along the shoulder of a road. He has received a notice in the mail that declares him the winner of a mail-order sweepstakes, and in the grip of a peevish, encroaching senility he determines to travel from his home in Billings, Montana to Lincoln, Nebraska to claim his “prize money.” Kate’s carping and David’s pleading fail to deter him, and so David gamely agrees to drive Woody there. En route, Woody and David stay with relatives in Woody’s Nebraskan hometown, which becomes a family reunion of sorts, with Kate and Ross eventually joining them. This unintentional homecoming becomes the center of the story, especially once Woody lets word get out that he is now a millionaire. For most of the picture, Woody is taciturn and cranky, but he surprises David by basking in the appreciative glow of being the hometown hero. Though Kate can’t understand this foolishness, David’s willingness to let Woody live out this lie becomes a mournful gift to his father, and a great act of kindness.

Given these themes and rhythms, and the film’s sense of humor, it’s surprising that Alexander Payne and his partner Jim Taylor didn’t write Nebraska (it’s the inaugural work of screenwriter Bob Nelson). Another author of the film is cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, who shot the plains of Payne’s home state like Ansel Adams capturing the epic grace of the American West — one of my favorite shots is of Woody and his brothers watching sports on the couch, a line of etched faces like Mount Rushmore. This formal choice curiously recalls Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha, also presented (if not originally shot) in luminous black-and-white. But if Frances Ha is spring, then Nebraska is autumn, the heat of youth versus the frost of middle and old age. Baumbach gave us Greta Gerwig pirouetting through downtown to David Bowie — buoyant optimism, a love affair with a fantasy of New York. But even just thinking about Nebraska brings on a wave of melancholy. Or to quote the twitter feed of film distributor A24: “NEBRASKA is rated R cause old people remind young people that eventually our bodies start degenerating and then we die.”

If Nebraska is unsentimental about mortality, about Woody’s loss of agency and his feeble, Quixotic attempts to wrest it back, it’s also compassionate and deeply felt. Credit rightly goes to Bruce Dern. From his corona of wispy white hair to the permanent slump of his shoulders, his performance lacks vanity but not dignity. It’s gratifying to see Dern getting the recognition he deserves, including a Best Actor win at the Cannes Film Festival (it’s easy to imagine other accolades following). There’s a tender irony in the fact that Payne’s story about the horizons of life is proving to be a comeback story for Dern at the age of 77. By accessing difficult truths about failures of the past and the cruelty of time, Dern has perversely given himself a second act.

What I come back to is the deep core of emotion in Nebraska. Woody is an easy target, and Payne deliberately fills his film with similar targets, especially the anemic small town of the heartland, with its small dramas and desires. But in its heart, Nebraska is a tribute. When Woody and David reach the end of the rainbow, the unglamorous office of the sweepstakes company, David apologetically tells the receptionist, “He just believes stuff that people tell him.” She shrugs, “Oh, that’s too bad.” That this scene plays like a triumph rather than a disappointment shows us how far father and son have traveled.

(P.S. Giving me one more reason to love it, BAM has also programmed “Hot Dern!”, a retrospective running from November 16-27 that features Dern in ‘70s films like Hal Ashby’s Coming Home and Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens.)

Filmmaker has partnered with our friends at Hammer to Nail for a weekly “Pick of the Week” post that will be exclusive to our newsletter and blog for a long weekend, at which point it will go live over at Hammer to Nail as well. In the meantime, be sure to visit www.hammertonail.com for more reviews and lots of other great editorial.