Back to selection

Back to selection

Sherlock Sr.: Bill Condon’s Mr. Holmes

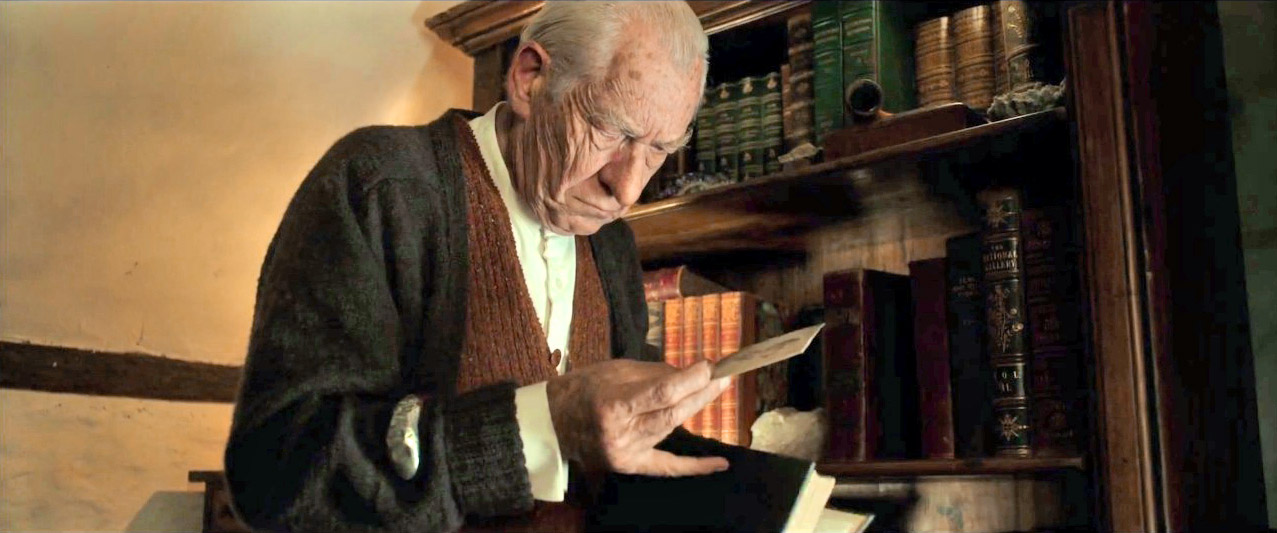

Ian McKellen in Mr. Holmes

Ian McKellen in Mr. Holmes We’re not in Victorian London anymore. Mr. Holmes takes place in the British countryside in 1947, two years after the end of World War II. Labor leader Clement Attlee holds the reins of power, and a new, heavily socialized country has begun to emerge from the wreckage of the Blitz. Sherlock is no longer searching for clues to a new case and logically deducing from forensic evidence and observation the course of events leading to a crime and holding the perp accountable. This film is not about the incarnation we are familiar with from Arthur Conan Doyle’s books and innumerable movies about the singular sleuth. This Holmes is a frail 93-year-old, 30 years into retirement.

Always a solitary man, Dr. Watson notwithstanding, he is now a recluse, having retreated to a farm with an old stone house in a verdant stretch of coastline Sussex. He wiles away the time going through old correspondence and photos and raising bees, which are mysteriously dying (but figure prominently as metaphors and plot points).

Carter Burwell’s somewhat sad music track of light piano and chastened cello is appropriate accompaniment to the unhurried action. Sharing vague recollections with us through the marvelous flashbacks of director Bill Condon (Dreamgirls) and editor Virginia Katz, this latest version of Sherlock in the smart, moving, and gentle film — a gorgeous widescreen enterprise (DP: Tobias Schleisser), adapted by Jeffrey Hatcher from Mitch Cullin’s book, A Slight Trick of the Mind — begins to obsess about the closed investigation that had caused him to stop working, but has festered in his psyche for three decades. He needs to unravel and tie it back up — urgently, the way very senior people, lacking the confidence of their younger days, often make choices.

Two events precipitate his journey to regurgitate the facts of the case and relay them in the form of a novella. The first is the sight of a faded photo of a beautiful young woman. The second is his going to the cinema to see a Sherlock Holmes film taken from one of the sensationalized scripts by hack pseudo-novelist Watson, whose penny dreadfuls (Holmes’s words) based on their cases had cheapened their work in forensics. The movie wrapped up the case on a patently false note. He wants, no, needs, to correct it for the record. (Mr. Holmes is a film rich in inventive metas — well-integrated stories-within-stories among them — the actual conclusion of that case the most impressive of all.)

The whole affair is relatively simple by Holmesian standards. Thomas Kelmot (Patrick Kennedy) hires the detective to follow his wife, Ann (Hattie Morahan), the woman in the picture, depressed (“a dangerous melancholy,” according to the husband) over the deaths of two unborn children. Thomas assumes that the woman who clandestinely teaches her to play the glass harmonica, an instrument traditionally associated with the occult, has put a spell on her. Holmes deduces that the wife is out to murder her spouse, but when he learns that that is not the case, suggests she return to her husband. This is one time he not only gets it all wrong, but he also allows himself to be manipulated like a marionette.

The memoir is problematic. Holmes is very fuzzy on details of the case, including the resolution, the facts underlying it, and why it has affected him so profoundly. The effects of age and suppression have given him a nasty bout of writer’s block. “The case was my last,” Holmes says in voiceover. “That’s why I left the profession. I decided to write the story as it was before I die.” He later adds, “I chose exile for my punishment. I have no idea what it was I did.” Sitting for long periods in his attic study, he spends more time trying to remember than putting pen to paper. Is he capable of distinguishing fact from illusion?

Simultaneously, he plunges into his memory bank in an effort to resolve another, more recent mystery: why a Japanese man chose not to return home from the U.K. when war broke out. The detective had been invited by the man’s grown abandoned son, Mr. Umezaki (Hiroyuki Sanada), to his country on the pretext of finding a natural brain-nutritious substance called “prickly ash,” for true believers much more potent than the more easily available royal jelly. Was the father cowardly or courageous? Holmes had even played a part in the man’s choice of allegiance, but what was it?

At an age when images from different time periods overlap more frequently in the brain, Holmes, whose short-term memory is rapidly disappearing, confuses the two investigations. Montage is a handy device for Condon to effectively conflate the barely tenuous connections between them. Conversely, in such a cerebral mix-up, solving one case might provide some answers for the other.

This is not the Holmes with trademark deerstalker and pipe of Basil Rathbone, Clive Brook, Robert Downey Jr., or, on British TV, Benedict Cumberbatch. He uses neither in Ian McKellen’s masterful interpretation, in which, as expected, the slightest facial gesture provides a wealth of information. (McKellen played a washed-up James Whale, gay Hollywood master of classic horror films, in Condon’s Gods and Monsters 17 years ago.) Sherlock has become a mildly eccentric country squire attired in pensioner-style cardigans and, when tending to the objects of his hobby, a silly beekeeper’s hat with netting. He is essentially alone, except for his no-nonsense live-in housekeeper Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney, appropriately dour, in her third outing with Condon, following Kinsey and The Fifth Estate), and worshiped by her energetic, precocious 11-year-old son, Roger (Milo Parker, brilliant and ingratiating), who helps with the apiary and excitedly proofreads his prose.

This Sherlock is more self-centered and much more at ease undermining others than his predecessors. “Exceptional children are often the product of unremarkable parents,” he casually tells Mrs. Munro during breakfast — in earshot of the impressionable Roger, who can’t help mimicking his idol. (“She can hardly read!” the boy taunts her in front of her employer.) In spite of his bon mots and astute observations, he is at bottom a frightened geriatric, attempting in vain to mask the fact that he can barely hold together his body and mind. “He doesn’t need a maid; he needs a nurse,” says the straight-shooting woman, who is both jealous and afraid of the old man’s bond with her son, who lost his father during the war and doesn’t need to relinquish another paternal figure.

Whether mother and son will leave or stay in the large dwelling becomes an important domestic issue that is a nifty fit for the new Holmes that emerges, a man who learns the value of affection, of what is distinctly human. It was the solitude he treasured that indirectly caused him to miss the ball on that final investigation. His departure from the field was tragic, given that he was universally recognized as the ideal practitioner.

In the flashbacks, we do see a younger (well, middle-aged), diligently working Holmes, dapper in top hat with cane, but most of the film focuses on his dotage and a much broader pursuit than rectifying the transgressions of others: He is the case. Reliving the two prolonged episodes teaches him that reason, which he holds in such high esteem (“I’ve never mourned the dead, bees or otherwise; I dwell on logic”) and imagination, which he so reviles (“I prefer facts”), must both be taken into account in any analysis.

He had just seen the bastardization of rational science while visiting the charred remains and scarred survivors in Hiroshima during his recent journey. (It is not accidental that this site exemplifying mankind at its most aberrant is a fertile spot for the growth of the brain-enhancing prickly ash.) Hiroshima is, according to Condon in an interview with Movies.ie, an example of “science without any sense of human implications.”

The place makes a strong impression on the British visitor. He learns that human behavior is often irrational, that the workings of the mind do not follow strict rules with a single interpretation. This is why Mrs. Munro and Roger must be present: He has close at hand real people on whom to apply insights from the tail end of his learning curve. Who else might reap the benefits of his belated recognition of the undeniable place of affection and emotion in our lives? The old man professes what had remained deeply buried in a powerful climax that yields to a Zen-like epilogue that gracefully brings the film full circle back to the opening, his return from Japan.