Back to selection

Back to selection

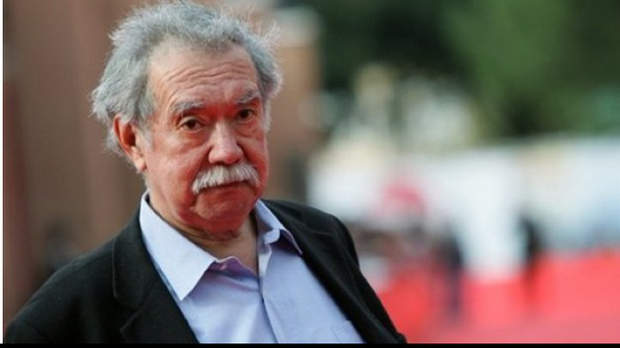

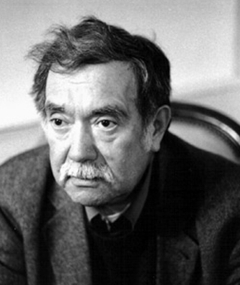

Raul Ruiz Remembered By James Schamus

The great Chilean filmmaker Raul Ruiz passed away today in Paris. Through his feature The Golden Boat, which was James Schamus’s first as a producer, Raul gave a group of us in New York’s nascent ’80s independent scene (including myself and Robin O’Hara) a wonderful and nearly indescribable introduction to filmmaking. So, I’m grateful here to James for this piece remembering Ruiz and those thrilling and formative days. — Scott Macaulay

Raul Ruiz: First Thoughts

Raul Ruiz passed away today, age 70, in Paris. He’ll be remembered as one of the truly great, idiosyncratic and visionary voices of world cinema. He was tirelessly inventive, gentle, profoundly uninterested in the business and hype of the film world, willing to show up anywhere a good crew and cast were ready to explore with him. He didn’t so much make movies as he lived one long continuously productive moviemaking life. Exiled from his native Chile in the wake of the CIA-sponsored 1973 military coup that upended its democratic socialist government, Raul landed in Paris. From there, one masterpiece quickly followed another: The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting, Three Crowns of a Sailor, Treasure Island. Over the next four decades his career (or rather the pace at which he produced films and videos) would ebb and flow, rising to new heights in the past few years with Time Regained and Mysteries of Lisbon.

Raul Ruiz passed away today, age 70, in Paris. He’ll be remembered as one of the truly great, idiosyncratic and visionary voices of world cinema. He was tirelessly inventive, gentle, profoundly uninterested in the business and hype of the film world, willing to show up anywhere a good crew and cast were ready to explore with him. He didn’t so much make movies as he lived one long continuously productive moviemaking life. Exiled from his native Chile in the wake of the CIA-sponsored 1973 military coup that upended its democratic socialist government, Raul landed in Paris. From there, one masterpiece quickly followed another: The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting, Three Crowns of a Sailor, Treasure Island. Over the next four decades his career (or rather the pace at which he produced films and videos) would ebb and flow, rising to new heights in the past few years with Time Regained and Mysteries of Lisbon.

For some of us in the New York independent film world, Raul played a brief but crucial role in our formation. He was, for me, instrumental in my start in the movie business. In 1987 I was a grad student, working on my Ph.D. dissertation on the Danish filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer, when I came across, in the Danish Film Institute archives, the manuscript of a screenplay Dreyer and his son had co-written in the 1940s on the life of Mary, Queen of Scots. I was thinking of ways to get into the film business, and came up with the rather absurd idea of trying to option the screenplay from the Dreyer estate, and from there to track down my idol, Raul Ruiz, and get him to make the film. I had been working as an intern at a small production company in New York, whose head, John Williams, let me write a screenplay for him and then offered me a job. John indulged my rather odd idea, I wrote to Raul, and he immediately responded.

Needless to say, Mary, Queen of Scots never got made. But the next year, when Raul landed a fellowship at Harvard, we agreed that if I and some friends could throw a small 16mm crew together for a couple of long weekends, and a few thousand dollars to fund the production, he would come down to New York and make a movie. The screenplay, by Federico Muchnik, who now teaches film in Boston, was a hilariously deadpan, blood-soaked, surreal romp through the New York art world. Jordi Torrent, who has since produced some beautiful independent work here and in Spain, produced alongside me. The late great New York avant-garde theater legend Michael Kirby starred, along with many members of The Wooster Group, for which I’d been doing some work at the time. Our production team included Robin O’Hara and Scott Macaulay, who’ve since gone on to produce something like 30 of the most interesting independent films out there – Scott, who was then the programmer at the avant-garde performance space The Kitchen, lent us office space, which also served as the changing room for porn-star–turned-performance artist Annie Sprinkle (who ended up with a cameo in the film, in which Raul insisted she be fully clothed, of course). Our assistant director was none other than Christine Vachon, and Maryse Alberti (whose recent work includes The Wrestler) shot the film. Jim Denault, who has since become a major cinematographer himself (Maria Full of Grace), was the key grip. Our main location was an empty loft on Bond Street that had just been vacated by the gallerist Mary Boone. Jim Jarmusch and Barbet Schroeder, among others, came by for walk-ons, as did theater artist Stephan Balint and the late novelist Kathy Acker. John Zorn composed the score. And lots of the current New York film scene had a variety of roles to play on the film: Scott Hamrah, for example, who now oversees with great critical perception the film writing at N+1, worked as our assistant editor; Filmmmaker‘s senior editor Peter Bowen can be found as a blood-soaked extra in a particularly mordant scene.

I will save the anecdotes for a probably never-to-be-written memoir — let’s just say there were a LOT of them. But each story is inflected by the benign, bemused, puzzled and puzzling presence of our cinematic hero, Raul Ruiz. He spent a very few days with us here in New York, and left us all inspired, bewildered, and more in love than ever with the possibilities that cinema could create, if we all worked together with mutual respect for each other and with a shared commitment to just jumping in and letting the film take us places we never really planned to go.

The Golden Boat — that was the name of it — was the first film I produced. Its final budget was in the tens of thousands, and we completed the film with the help of a lovely Belgian father and son who were interested in supporting alternative cinema. Jordi and I raised the rest of money from friends and family – my fiancée drained the entirety of her savings account — $500 – to buy shares in the limited partnership. The film, of course, lost every penny put into it. A couple years later, when I got my first profit participation from The Wedding Banquet, I sat down and wrote a couple of dozen checks to everyone I knew in New York to buy back their shares, though one check, to my friend Casey Finch, I never got to write — I dedicated my dissertation to his memory instead.The film ended up doing some business. I remember renting one of the tiny “black-box” screening rooms at the Berlin Film Festival market, back then held in the old Kunsthalle. Six attendees shuffled into the space; four of them chain-smoked through the screening, the other two appeared to be high school students who had sneaked into the building, and who sat in the back row laughing uproariously (hashish, I thought?) at every twisted joke. Afterwards they introduced themselves, and that’s how I met Jon Gerrans and Marcus Hu, who were just starting Strand Releasing. They acquired the film for a not-high four-figure sum.

It’s impossible to know where all of us would have ended up had Raul not appeared in our lives for those few (though, admittedly, long) days. For some, the film was an experience and a notch on a resume; for others, like me, it was a decisive moment, when the Master arrived, and made of us, through his generosity and acceptance, not students, but colleagues. His visit to New York was a footnote to his own career: it was the first chapter to the life’s work of so many others.

Raul is survived by his wife, Valeria Sarmiento, a great filmmaker in her own right. — James Schamus