Back to selection

Back to selection

Big Ears Opens Its Eyes: The Public Cinema at Knoxville’s Big Ears Festival

Something Between Us

Something Between Us Since its first edition in 2009, the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, TN has earned a reputation as a daring music festival whose eclectic lineup is unfettered by commercial or corporate concerns. Artists run the gamut: avant garde jazz (Anthony Braxton), experimental hip hop (Shabazz Palaces), electronic (Nicolas Jaar), modern classical (Philip Glass). All of this takes place in remarkable indoor venues within walking distance of each other in the city’s downtown center. Governed by the idiosyncratic taste of its founder, Ashley Capps of AC Entertainment, Big Ears has attempted to expand its scope into film and video. In the 2015 edition, there was a retrospective of Bill Morrison’s work with a live score. Less successful was a selection curated by Jim Jarmusch and Swans’ Michael Gira of movies from the Criterion Collection. Hardly anyone showed up — how do you choose to sit in the cinema when you could be watching Max Richter perform in a beautiful venue on the very same block? That’s where The Public Cinema came in for 2016’s edition, which wrapped up on April 3rd.

Founded in 2015 by Something Anything director Paul Harrill and critic Darren Hughes, The Public Cinema is a microcinema with the stated goal of bringing “the best of contemporary international, avant-garde, and American independent cinema that wouldn’t screen in Knoxville otherwise.” This year, Harrill and Hughes are the masterminds behind Big Ears’ first full fledged film program. The Public Cinema was already in negotiations to screen Heart of a Dog as part of its spring series when AC Entertainment announced Laurie Anderson would be returning to Knoxville. “We’d already been in contact a bit with Ashley Capps,” Hughes explains, “so we pitched him the idea of postponing the screening until Big Ears in hopes that Laurie might join us for a Q&A. He loved the idea and invited us in for a larger conversation”.

In addition to Anderson’s film, The Public Cinema brought in a gorgeous 35mm print of the singular ’70s Sun Ra vehicle Space is the Place, which had recently played in (and given the title to) BAMcinematek’s Afrofuturism on Film program. Both it and Heart of a Dog took center stage and screened in Big Ears’ most lavish venue, the Tennessee Theatre. More specialized programming played at more modest spots. “10 By 25,” a retrospective of ten films distributed by Factory 25 — Matt Grady’s offbeat label known for distributing films by Joe Swanberg, Alex Ross Perry, and other indie auteurs — played at the local multiplex through the festival’s final day, after all but one of the musical acts were over, making for a relaxing hangover retreat after a whirlwind of venue-hopping activity.

“Every musical performance is, by definition, a unique event, so we knew we needed to give audiences a reason to choose a film,” Harrill said. “In that sense, the Factory 25 retrospective felt like one of the bigger risks, but like the music at Big Ears, there’s an eclecticism and daring to the F25 films we screened. My gut told me that if we could get audiences to attend a few of the films they’d understand what we were doing and embrace it. I think that happened.”

“At a festival where artists like Keiji Haino, Tanya Tagaq, and Faust draw large and enthusiastic audiences,” Hughes explained, “there was no danger of programming work that was too difficult. Rather, the main pressure we felt was to get over the intimidatingly high bar that had already been set for us. Inviting Shambhavi Kaul and Jodie Mack was also a strategic effort to create cinema ‘events.’ Kaul and Mack are both dynamic and compelling personalities who integrate performance into their work, so they seemed a natural fit for Big Ears.”

Shambhavi Kaul’s Planets featured five films by the video artist, with thoughtful and good-humored live readings in between each that brought another dimension to the work as well as an inviting playfulness. The pieces — works of appropriation (Mount Song) as well as those made from original footage (Night Noon) — all challenged notions of place and representation, a sociocultural and ontological investigation into the properties of the film image as a deceptive window on a suspended moment in time. Kaul also had a complementary six-screen video piece entitled Modes of Faltering installed at small local gallery around the corner throughout the weekend.

Acclaimed experimental filmmaker Jodie Mack brought her well-traveled five-film presentation and live performance Let Your Light Shine. The centerpiece is Dusty Stacks of Mom, set to a rewrite of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon which Mack sings (and raps!) live. Her infectious energy and stunning forays into abstract animation were more than enough reason for a full house of Big Ears regulars to attend. A mix of film fanatics and curious festivalgoers made for a fresh audience who may not have had the same frame of reference as a typical film fest crowd but were nevertheless intrigued and delighted by Mack’s dazzling work.

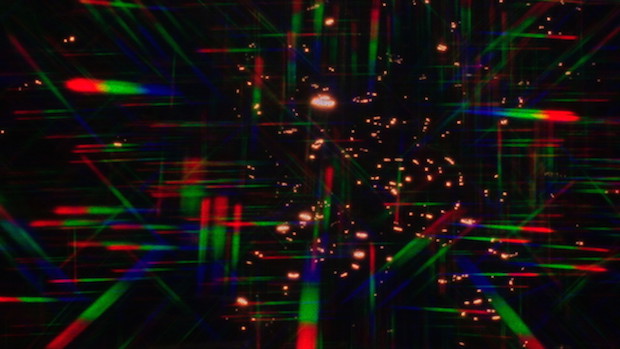

Two shorts programs under the banner of “Flicker & Wow” featured world class experimental films from the US, Canada, Argentina, Spain, Iran, and elsewhere. Mostly an effort at best-of curation from festivals such as Ann Arbor, TIFF’s Wavelengths, NYFF’s Projections, and Locarno, the films were largely listed as “Southeast Premieres” that would likely have otherwise gone unseen by those in attendance. Both programs played well, highlighted by Chicagoan Calum Walter’s disorienting Terrestrial, a chilling in transit experience through both sky and subway, Pablo Mazzolo’s mesmerizing Fish Point transforms a nature reserve in Ontario into a earthy yet placeless shuffle of shifting super-impositions. Best of all, Mack’s recent live action work, Something Between Us, brings together electronic music, trinkets, and natural beauty in harmonious prismatic rainbows of light. The first night of shorts was bolstered by the world premiere of Bill Morrison’s The Dockworker’s Dream, scored by nearby Nashville residents Lambchop, who also performed at another venue.

One mark against the projections in The Square Room was the absence of celluloid, the ideal material of choice for nearly all of the screened works; it was both endearing and intrusive to see VLC player controls pop on the screen before each film. But with Capps’ chance taken on The Public Cinema having paid off, one can hopefully count on up-scaled resources at next year’s edition, now that Big Ears will be known for having an equally strong curatorial voice in its film programming. The unique and untainted mingling of music and film (far removed from the capitalistic fanfare of SXSW) and the emphasis on event-based screenings make Big Ears an evolving festival to keep your eyes on for audio- and cine-philes alike.