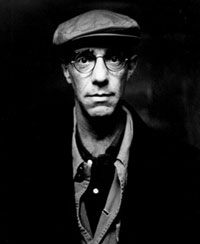

IN THE COMPANY OF SAINTSDerek Jarman’s Wittgenstein and Beyond.By Peter Bowen.

On Sunday, September 22, 1991, the local order of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence guided Derek Jarman into his garden where, after a sweet and solemn ceremony, they canonized him — Saint Derek of Dungeness of the Order of Celluloid Knights. The Sisters, whose universal mission is “to expiate homosexual guilt from all and to replace it with universal joy” had bestowed this title on Jarman for, as they explained, his films, books, and good deeds, as well as his “very sexy nose.” Even though the good sisters warned him not to let all this go to his head, Jarman confesses in his autobiography, At Your Own Risk: A Saint’s Testament, that he “had to take it seriously.” But even if Jarman’s title, much like the chants and prayers of the gay nuns who canonized him, is intoned with tongue-in-cheek, there is something about this Catholic appellation that fits Jarman all too well. Is it any coincidence that the dialogue for his first film, Sebastian (1975), was written in Latin, a language dead to all but the priests who evoke it in Catholic mass? Or that in his latest film, Wittgenstein — which is to be released this fall by Zeitgeist — the famed German philosopher, a figure whom many insist on seeing as a stand-in for Jarman himself, ironically explains why he is not a Christian: “I look at everything from a religious point of view. Why is there anything at all, rather than just nothing?” Why indeed? For Jarman, whose work seems to grow from political anger and indignation as much as from an aesthetic love of beauties, the answer might be as simple as the ACT UP slogan, “Silence = Death.” Having tested positive for HIV in 1986, Jarman has in recent years been producing work at a rate equal to, if not greater than, the virus’s growth in his own body. However disconcerting, Jarman’s notes in his production diary, Queer Edward II, about his hospitalizations and fevered temperatures, dropped in as they are among so much gossip and dialogue, remind us, as they continue to remind him, of the urgency to work. But even if there was not an AIDS epidemic, there would be enough brutality and beauty around to keep Jarman busy. Even now, as newspaper headlines declare Wittgenstein to be his Last Picture Show, Jarman is enthusiastically championing his latest piece, a radioplay/film entitled Blue, which he will show at the New York Film Festival this fall. For many, Wittgenstein’s depiction of the relation between life and work, or better, life-as-work — in both the sense of an artifact and as a tedious act of labor — suggests an autobiographical bent. It is a comparison, however, which Jarman is quick to correct: “No, no, it’s not personal at all ... I think that all films are personal, but I don’t think that all works are particular. I mean, I don’t think that I particularly identify with Wittgenstein. He was a bit stiff.” And while Jarman sounds a bit more excited about other 20th-century gay thinkers— “Now Alan Turing [the gay mathematician who broke the Nazi code] would be interesting” — Wittgenstein was work for which the money was already in place. “I wasn’t doing anything at the time, and Tariq Ali [the producer] approached me about doing a film on Wittgenstein for television.”

But what makes a film “a Derek Jarman film?” In no small way, Jarman’s sensibilities so often possess his subject matter that one is left with the uncanny sense that his films, like so many coded messages, are inevitably about Jarman himself (his adventures, his friends, his crushes, etc.). Indeed for someone whose films have provoked such controversy, his source material hardly seems a school for scandal: an early Christian martyr (Sebastian), a Shakespeare play (The Tempest), Shakespeare sonnets (The Angelic Conversation), an Italian Renaissance painter (Caravaggio), a 16th century English history play (Edward II), and a brilliant, but oddball, German Philosopher (Wittgenstein). But in the translation of these arcane subjects to film something strange continually seems to occur. Culture, as the annoying inheritance of nations and empires, becomes, at least in the time frame of his films, Jarman’s private property and playground. As such, Jarman’s films are rarely quiet events. In 1976, for example, The Gay News proclaimed Sebastian as “a quite remarkable film that represents a milestone in the history of gay cinema.” In 1983, the London paper The Star headlined the same movie as one of “the films which should never be shown to your kids,” and Channel Four, which had just bought the film, rushed to make clear they had no intention of showing it (to kids or adults) in the foreseeable future. A sparse re-telling of a Roman soldier who becomes a Christian martyr, the film’s unabashed homoeroticism— as well as its unsheathed erections — raised more than just a few eyebrows. It raised considerable questions about the ways in which traditional cinematic images have painted period pieces — specifically the homoerotic tales of Ancient Rome as heterosexual. Of course, Jarman’s use of St. Sebastian was no accident. At least since the Renaissance, the image of St. Sebastian (his pretty boy mouth, his near-naked body bound to a stake and penetrated with arrows, his closed or helpless eyes) has served as a flashing icon of homoeroticism for painters and Calvin Klein underwear ads alike. This strategy of cornering a particular historical moment or text and inviting it to speak on matters that proper culture has forbidden it to mention has become Jarman’s trademark. But rather than produce interpretations, or even re-interpretations, Jarman’s possession of the material becomes so personal and complete as to make it feel like an original work.

According to Jarman, “Eagleton went crazy for altering his work. Well I said to him, ‘I’ve got to make a film, I am terribly sorry and all that but I could not possibly have made a film from your script.’ And now he is stymied. I had special screenings for old friends of Wittgenstein and they loved it. They said that it was just like him. And the scenes in bed, well, they were uncannily accurate.” But the real issues underlying this argument, like the controversies that preceded it, have more often been about the nature of filmmaking than about Wittgenstein. In a BFI publication on the making of Wittgenstein, Eagleton introduces his script with a general discussion of the philosopher, while Jarman’s introduction, “This is not a Film of Ludwig Wittgenstein,” turns this studied film about philosophy into a carefree “philosophy of Film.” “Have no plan,” Jarman advises. “Then you can allow your collaborators to take over.” In an interview on The Last of England, a non-narrative silent feature in which the actors helped figure out the story, Jarman responded to the inevitable question about why he makes films with the simple response: “For the camaraderie.” In the making of Wittgenstein, Jarman details how he responded to producer Ali’s request to make the film 20 minutes longer: “I called in the actors and we sat down and worked out the lines.” In his close personal relations with his actors, the lines between on and off set began to blur. In the making of The Angelic Conversation (1984), a ghostly imaging of different Shakespeare sonnets shot in single frames of Super 8, the casting was made to cooperate with the story. Having been personally attracted to the first actor, Paul Reynolds, Jarman let Paul pick out his co-star when they were out one night. “I am making a film with Paul,” Jarman told the stranger, “and we think it would be great if you were in it.” When the man accepted, Jarman recounts that he “filmed the love affair between them.” Recently Channel Four’s refusal to accept Jarman’s casting for a film version of James Purdy’s Narrow Rooms shut down a production that would have followed on the heels of Wittgenstein.

If Jarman has been a stop-gap in films with lesbian and gay themes, he has also helped reinvent modes of production and financing. As with many independent filmmakers, Jarman’s rule seems to have been that budget is the mother of invention. But rather than either wait for support or cut back, Jarman has created images that he both wanted and could afford. Clearly much of his style comes from his background as a graphic artist. Having been trained as a painter, Jarman did set design for several operas and was the production designer for Ken Russell’s The Devils and Savage Messiah before turning to making his own films. (In 1980, he joined up with Russell again, creating set designs for Russell’s production of The Rake’s Progress.) It is precisely this painterly use of color and design that often defines Jarman’s cinema. In Caravaggio (1986), the still-life tableau vivants of the painter were memorable enough to reappear in REM’s “Losing My Religion” video. In The Last of England, Jarman paints the fate of his homeland in a series of scenes that seem to oscillate between grandiose allegorical paintings of national history and cramped punk performance stages. In Edward II (1991), grey walls serve as a high fashion backdrop to the faux Chanel cocktail dresses of Tilda Swinton, the offended queen of the queer Edward. And in Wittgenstein, Jarman changed the Cambridge exteriors of Eagleton’s script to a soundstage hung with thick black curtains. “We never could have afforded his locations,” Jarman explains. “So we decided to shoot cheap bright colors against black. I think it turned out rather well, don’t you?” The look, as elegant and provocative as Wittgenstein’s thinking, produces the eerie floating feeling of a life remembered at nighttime. The only time the set actually opens up, and then only to pink and blue fields of ice, it is a fantasy of a world too perfect to be real. While Jarman’s film’s have never been real, they have nevertheless been realistic. In the beginning of the production diary Queer Edward II, Jarman offers young filmmakers a note of advice: “To make a film of a gay love affair and get it commissioned, find a dusty old play and violate it.” His comment, which ridicules production companies’ willingness to fund “the classics” at the cost of current gay stories, also highlights Jarman’s skill at finding money. In defending his use of Super 8 in The Last of England, Jarman jokingly sings “My friends, the bluebells are flowering in the woods of Kent — now do you wait for someone to tell you you can film them? They will have died before you get an answer.” While such utterances ring mock heroic, they also ring the sense of humor and urgency that has carried his work forward. Told not to let his sainthood go to his head, Jarman could hardly help but remember that he was the first “Kentish saint since Queer Thomas of Canterbury, who was murdered by his boyfriend, Henry, in 1170.” So much history, danger, and responsibility. As he reminds us at the end of At Your Own Risk: “It is no small thing to be made a saint, especially when you’re alive and kicking and have to give your consent.”

|

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →