FADE TO PARADISE

Scott Macaulay Interviews Victor Nunez.

|

While Ruby in Paradise, Victor Nunez’s invigorating new feature, may concern itself with tourism, it’s not the least of the film’s many virtues that it avoids feeling like a tourist in its own locale — America’s changing South. Set in Panama City, Florida, a middle class vacation spot known to Nunez during his childhood as the “Redneck Riviera” (and now being transformed into a condo-lined resort), the film, with its luminous Super 16mm photography, poetic use of natural sounds and distinctive room tones, and expertly cast collection of memorable characters, demonstrates a sagacious feel for the roots, rhythms, and realities of contemporary life all across this country.

Nunez says that after reading his original script, financiers rejected the film, calling it too “European” for today’s market. The film does have a refreshingly relaxed pace and contemplative mood but, rather than referencing some kind of existentialist ennui, these qualities help the film in its matter-of-fact critique of American patterns of work and leisure.

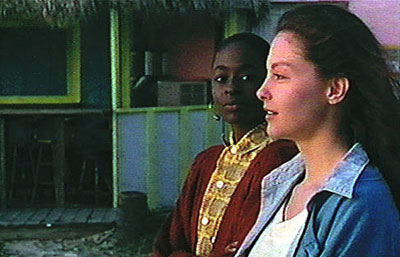

While the film unselfconsciously engages a myriad array of contemporary issues, not the least of them gender-related, its protagonist’s attempts to define herself in the modern workplace resonate with Nunez’s; own recent experience. After completing his second feature, A Flash of Green, in 1985, Nunez spent years trying to get Ruby off the ground. After countless rejections, he began to question his own relationship to filmmaking. Living in Florida and not interested in the latest indie film flavor of the month, Nunez began to feel like an outsider to the profession he had spent his life trying to practice. Then, after he made a decision to himself to proceed with the film at any cost, he suddenly found financing. Similar fate connected him with his star, Ashley Judd, who dropped into the lead role during Ruby’s brief L.A. casting sessions. Although Judd is an experienced performer known to television viewers for her work on Sisters and Star Trek: The Next Generation, it would not be an insult to say that she demonstrates here the unaffected charm and presence of a non-actor. Steering clear of melodrama and cliché, she develops her role so naturally that one easily identifies with the drama inherent in the character’s trek through a landscape of spring break beach scenes, trinket shops, and anonymous hotel discos.

We spoke with Nunez at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, a day after the film’s premiere and just a few days before it would win the Grand Prize. Ruby in Paradise opens this fall from October Films.

|

Filmmaker: Your film very naturally but very specifically evokes a real sense of place. How does your view of the South differ from the image of the South found in mainstream movies like Steel Magnolias?

Nunez: This came up in the regional panel discussion yesterday, and several of us said that the most terrible “regional” movies are the ones that are from Hollywood. They come in and they turn on the accents and turn on the clichés and the gestures. I think about regions...there’s a lot more in common than less in common when you really get far enough underneath. I’ve always been drawn to the Italian neo-realist manifesto of character, place, and story being somehow inexplicably linked. In order for a story in film to reach a level of universality, it has to first reach that level of the specific. It doesn’t matter whether it’s set on a street in Brooklyn or the Gulf Coast. You have to feel and know where that place is.

Filmmaker: The film deals with leisure time, the different ways different people spend it. There’s almost an anthropological take on the American middle class at play — for example, that spring break beach party at the end of the film.

Nunez: I think one of the things about growing up in Florida is that you are very aware that you are at the place where people want to go. This is the reward and so you are in paradise. Very early on you begin to look and try to define what [that concept] means to people and how it relates to the rest of what a person has to do in life. On the most basic level, the place is the “resort,” which has a wonderful double meaning. I’ve never quite understood why it both has this meaning of a place you go to relax and escape and also as “the last resort.”

Filmmaker: What was your starting point in developing the story, characters, and place of Ruby in Paradise?

Nunez: The first ideas are notes I had about three years ago. I’ve always been fascinated with Panama City the beach and the town — because it’s still, in many ways, the Florida I grew up in versus what Florida is very fast becoming. Somehow, because it’s stripped of the glamour and the layer of money, it’s more elemental. Panama City has always traditionally been the working class beach of Florida. It’s always been jokingly called “the Redneck Riviera.” I grew up and lived for a time in a house where the sand came up to the back door. It’s a world that I have some connection with. Ruby was this inner saint that needed to discover being in a film. Life for me was at a point where I didn’t know if I was still a filmmaker or not. On the more practical, external side, I think among women in the last 10 or 15 years is this issue of “how do we define who we are, now in this time?” It seemed very important that [Ruby] be a woman trying to figure this out.

Filmmaker: How did you go about developing the script from that idea?

Nunez: To be honest, I’m quite astounded that the structure of the script is very much what the very first outline was. I spent a year working on the script. It’s such a simple story that you wonder “How is that possible?” but obviously, when you’re trying to get things down to this very lean level and you’re trying to do something which you know goes against the conventional grain...

Filmmaker: As a filmmaker working outside of New York and L.A., working in the South, what are the practical realities and the problems you face in terms of production and financing?

Nunez: In terms of production, it’s actually quite encouraging. The technical means of production are everywhere. Our sound was done using an audio system that’s based on the Macintosh computer. It’s a system by Digidesign called Protools. It’s amazing. One of the things that’s nice is because we were in Tallahassee, Digidesign let us be a Beta-test site for a critical piece of equipment called a SMPTE Slavedriver which allowed us to sync our Moviola 24-framed SMPTE to 17, 18, 20 tracks of audio. You can only hear four at a time but you can build everything, all the dialogue and everything. So the means of making really good movies — and soundtracks are increasingly critical because sound has become so good in all films — are there. I think as far as crews and personnel, it’s harder because everybody’s scattered. Young crews in the South, by and large, have done so much commercial work. If I’d known that, I would have written in another week of reeducation that had to take place. I convinced [the crew] that we were really doing something different, which they could not believe for a long, long time. They just thought, “this is just like everything else.”

Filmmaker: What did this reeducation entail?

Nunez: There was a sense that we’d want to haul out everything for every shot for every location. It was kind of a subtractive concept of doing the set-ups and production whereas we had to deal with the notion of additives. What is the minimum? What is the source of light and how do you build from there? It’s a fundamentally different concept, and it’s the only way that you can work in a small film. You can replace the money part with speed. By the end of the shoot everybody was up to speed and I think that, while the film is rough, there are still some very beautiful things in the movie. You have to work very fast. I’m a great believer in Super 16. Every movie I’ve ever made has been Super 16. The film stock is getting better. You save so much money. Anything under a million and a half dollars... Five years ago the networks shot 35mm for television and now they only shoot Super 16. Laurel is planning to use it for an eight hour mini-series. It’s a wonderful format and I don’t think people understand how much it saves in post as well.

Filmmaker: What about in terms of financing? You’re outside of the money centers.

Nunez: Financing is no harder or easier than anywhere else, and in fact, no one would give me money for Ruby in Paradise. It’s a fact that I was able to make this movie almost by a fluke. I had decided that I was going to make it no matter what. I had a great aunt who’d passed away and left me what was left of her trust. And I was able to borrow money. Basically, this is one of those movies… like, I am totally in debt. I never thought I would do that, but it was, again, if I’m going to be a filmmaker, I’ll have to do this. I feel like it wasn’t totally an irresponsible act, because, after all, I had made a few movies before. But had I [not inherited money], I would not be here with this movie. There were no sources of financing that I could find and I tried everything.

Filmmaker: Did people come in later when you were finishing?

Nunez: Nope. Basically the line was that it was not American enough. It was not hot enough. It was not cool enough or urban enough. Those were the buzzwords at the time when I was trying to get money. I don’t know what they are now, but they’re probably something similar. There was some money that almost came in for finishing because I really initially only had enough to get it into the can and then get it into post to work on it. You all ought to do an article about these finishing funds that are floating around. I think they’re criminal. They hit filmmakers when they’re at their most vulnerable, when they desperately need $10,000 or $15,000 or $20,000 or $50,000 and they say “Sure, we’ll give it to you but we want half your movie,” or ‘We want twenty percent of our money plus …” It’s like, “Oh my God,” I mean maybe that’s considered good business but it seems to me that it’s not the kind of thing that ought to be happening in independent film.

Filmmaker: What sort of budget were you working with?

Nunez: I think it’s important [to discuss budgets]. It used to be that people were very cagey about it. Irwin Young at Du-Art allowed us to pay a third of our dailies’ cost and the rest was due at the end of the year. We got it into post for $350,000. Post, because there were very few of us working, was about $30 -$40,000. And then of course that’s when the big money hits again and the negs cost around $40,000. By the time, and again this is not hard and fast, by the time every bill gets paid to get the film here, it will be about $600,000. By the time everybody gets paid, again in what I view as very real deferrals, the film will be at $750 - $800,000.

Filmmaker: And how long to shoot the film?

Nunez: Six weeks principal photography, then we had a day and half in the Tampa location and then about two days of pick-ups.

Filmmaker: You operate the camera on all your films.

Nunez: I’ve always done it. I came up and started in the experimental film days and it has, again, something to do with speed. Just one less person that you have to talk to. Also, basically when you’re a filmmaker/producer, you’re right at the spot where you can make the decision about whether or not that shot is good enough. Basically, when you make low-budget films, you live in the “good enough” mode by and large. And if you’re lucky, you’re moving fast enough and everything is flowing well enough that “good enough” is what you need. If there’s a little bump in the camera move or something, you can decide. The other much more fundamental thing for me is that it’s the only way that I’ve known how to really look at performance because, for me, moving the camera one inch in any direction affects the performance and affects what is being seen of a character and, more importantly, what is being seen of the inside of a character. I don’t quite know how to do that when standing 20 feet away.

Filmmaker: How did you cast your main actors?

Nunez: A wonderful casting director named Judy Courtney who’s worked on a lot of independent films in the past and she’s also worked on a lot of commercial pictures. She’s what I think an independent needs when they have to interface with an existing power structure – infrastructure is a better word – and, in the case of casting, with the agents and that whole world. I truly believe that what an independent film can offer actors is the opportunity to really create characters. And unless you’re on the A-list in L.A., you’re not going to get much challenging work. Judy had two weeks of casting prep and then I was in L.A. for ten days and we cast the picture. And, as she says very philosophically, that had we cast it two weeks earlier or two weeks later, it would have been a different cast. I’m very glad it’s this cast, I think it’s a wonderful cast.

Filmmaker: As someone who has been a part of the world of independent film as long as it’s defined itself as such, what advice would you give to beginning filmmakers?

Nunez: I think it takes a long time to learn to be a filmmaker. I used to say if I live to be 200, I might get what I need to do done. I’d tell them to not forget the past, even when you’re young. I know the temptation is to believe that everything that’s of any significance happened within the last six months. Have a sort of humorous sense that we live in a culture that is so event-oriented and so insure of itself that it has to feel like it’s in on the moment and movies don’t get done in moments. You have to at least develop in yourself a bit of a longer window or a long view of things. Maybe realize that you share things not just with your contemporaries and not just with those still living but also with those who aren’t here. Film is as much about literature and other things that have happened as it is about the films that have been made within the last five years. That kind of pontificating said, also remember that you ought to have genuine fun making a movie. It ought to really mean something first to you. If the reason you’re in independent film is because you want to get into Hollywood, know that about yourself and know that it’s both a strength and a profound weakness and that you have a shot at it. But there are other things that film and independent film can be and I hope I remain as despairing and as hopeful about what independent film can be as I did all those years ago when the IFP first met in New York and said, “Maybe we ought to get a group of people together, we all seem to be trying to do the same thing.” Strength in diversity and all of our little mottos back in those days when there was no East, West, South, and North. There was just one Independent Feature Project.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →