FLASH IN THE PAN

While Pecker, the artist hero of John Waters perceptive new comedy, may be an overnight sensation, Waters the filmmaker is not. For over 25 years Waters has explored the frontiers of American cinematic taste while bringing a casual intelligence to bear on a variety of provocative themes and has fashioned himself into one of our foremost auteurs. Peter Bowen chats with Waters about artmaking, Baltimore, magazines, and Pecker.

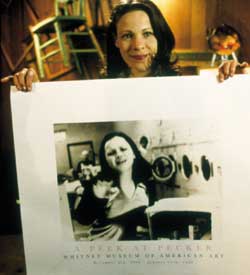

Edward Furlong as Pecker. Photos: M. Ginsburg/Fine Line.

Few American directors embody the role of the film auteur as successfully or as quirkily as John Waters. Long before the Farrelly brothers made gross glamorous, Waters was expanding our sense of cinematic pleasure to incorporate the abject and objectionable. But while both critics and cultists have been quick to anoint Waters "the Baron of Bad Taste," such a simplistic title misses the democratic thrust of Waters' work. From his early "Dreamlanders" films, which include the infamous Pink Flamingos, to Hollywood-funded projects like Hairspray and Serial Mom, Waters, like de Tocqueville, surveys the borders and benefits of American democracy.

Having in earlier films sent up America's neurotic fixations on taste, race, gender, crime and bodily functions, Waters now focuses his gaze on art – and the peculiar way in which it is discovered, apprehended, and evaluated in this country. In Pecker, an artistic naif (Edward Furlong) from Baltimore who makes photographs of his friends and neighbors is discovered and championed by an art-world maven (Lili Taylor), only to discover the sadness of success.

Filmmaker: Speaking as one of our most recognizable American auteurs, how would you end the Monica Lewinsky story if it were a John Waters film?

Waters: First, I would never make a movie about Monica Lewinsky. But I think the affair will come down to Clinton telling the Supreme Court, "She blew me, but I didn’t come." The film would be called Monica’s Dress and would begin with a close up of the stain, the supposed Presidential load. A week later, drag queens would be wearing it as a pattern. And the film would end with the Supreme Court deciding whether a blow job that does not end in ejaculation is in fact sex.

Filmmaker: I ask this because many of your recent films seem culled from current affairs.

Waters: Not really. Serial Mom was done before O.J.; if anything, it was based on the 500 true-crime books that I have in my apartment. And Pecker was based on a piece in Newsweek that said, "If a modern photographer is taking your picture, run for your life." That gave me the idea for the movie. It was not based on any particular photographer or me at all. Some things that happened to Pecker happened to me, but I was never like Pecker. I was never naive; I was in on it from the start. If anything I am little Chrissy. C’est moi. I just want to eat candy.

Filmmaker: Well, I know you are a bit of a media junkie, so how does all that information make it into your films?

|

| Director John Waters |

Filmmaker: In that case, where did the title Pecker come from?

Waters: I just love that word. I had a film called Glamourpuss with a movie-star stalker [character] called Rodney Pecker, and there was a different character in drafts of Cecil B. Demented whose name was Pecker. It’s a very funny word. You can’t talk dirty with it. Who, for example, would ever say, "Suck my pecker?" Certainly no man wants his penis described as that. But really, of the eight million times the word is said in the movie, it is never sexual. It is always his name. Originally the MPAA denied us [the right] to use that title, and eventually they overturned themselves. If they hadn’t, I don’t know what we would have called the movie – Pucker? Picker? Packer?

Filmmaker: What does the name Pecker mean to you?

Waters: For Pecker to be Pecker, he had be handsome but nerdish, so cute he didn’t even know it, which to me is best look that anyone could possibly have. Lili Taylor says in the film, "We don’t have boys that cute in New York." That’s not true. It is just that everyone who is great looking in New York knows it. In Baltimore, there are a lot of people who could knock ’em dead here [in New York], but in their own neighborhoods people think they are ugly because of that thin gray line between ugly and beauty.

Filmmaker: What passes for beauty in Baltimore?

Waters: It is very, very different than what passes for beauty in New York, and that difference between the two cities is somewhat the point of the movie. I joke that the poster should read "...and the curtain of irony that separates the two."

Filmmaker: While Pecker deals with an artist and the art world, the film seems to be more concerned with aesthetics than art, that is, more with the theory of beauty than with what passes for it.

Waters: And how, when it is taken out of context, it changes. Pecker’s family seems very normal to him, but when [they appear] out of context on the cover of ArtForum or in the New York Times, then everyone looks at them in a very different light. And people can never get that context back.

Filmmaker: There’s a remarkable moment in the laundromat where Pecker shows Shelly (Christina Ricci) the inherent beauty of color, even in stains.

Waters: That scene is really against the contempt for investigation, which almost all regular people have about contemporary art. You show them something, and they start sputtering, "Jeez, my kid could have done that." Of course! That’s the kind of art I like, where you have to learn to look at it in a different way. If there is one, that’s the message of every movie that I’ve ever made.

Filmmaker: Even though critics continually dub you a promoter of bad taste.

Waters: The Anal Anarchist, the Duke of Dirt, The King of Puke... I have many titles. Personally I love the The Ambassador of Anguish because my movies are anything but that. They are really joyful, except maybe for Desperate Living.

Filmmaker: I was surprised what a feel-good movie Pecker is, especially in the way it ends with such a raucous scene of harmony.

Waters: That last part is my dream, my ultimate bar. I would go there every night – the New York art world, male and female strippers, blue collar Baltimore, all together with their families, and everyone on drugs and liquor. That’s my idea of a perfect night. I think that scene contains the two things that make for happiness: one, people make fun of themselves and learn to have a sense of humor; and two, they are turned on by people outside of their own class.

Filmmaker: What are the traditions out of which your work comes?

Waters: It’s a mix of three types of film I experienced growing up that were all fused together for me. One is true American Underground film – work like the Kuchar Brothers, early Warhol, Kenneth Anger. That put together with every film I ever saw at the drive-in – exploitation films, nudist camp movies, movies that were exploitation before porno changed everything. And the last element was Bergman and European art films. Bergman was shown at the dirty movie theater in Baltimore. Those three influences all had something forbidden in them. People then might have seen two of those genres, but I don’t think that anyone rabidly saw all three. In my mind, I put them all together, and they became one for me. Art films, like Claire Denis’ I Can’t Sleep, remain my guilty pleasure.

Filmmaker: Pecker seems to comment on your own filmmaking process.

|

| Lili Taylor as Pecker's Art Dealer |

Filmmaker: I was thinking more about the way in which the New York art scene reads Pecker’s work as a photographic exploration of the ugly, when to him it was all about finding the beauty in things.

Waters: Well one big difference [between me and Pecker] is that, as I said, I was never naive. What is similar is that the minute you have any success, everyone thinks that you are rich. As any filmmaker will tell you, if you ever see a nickel, you’re lucky. It is also true that people have come to Baltimore and asked me to show them hairdos on demand, as if I could take a news crew, burst into a bar, and yell, "There’s one!" What is also true is that many women friends in the art world or in show business come to Baltimore, get cruised by straight men, and get laid. And they never do in New York, because they are usually in gay surroundings.

Filmmaker: What about the inverse – gay boys looking for a little action in Baltimore?

Waters: As Tina says in the movie, Baltimore is the trade capital of the world. That’s not a lie. There is no such thing as a totally straight boy in Baltimore. And there are lots of closet queens who might for one night be horny. As a smaller town, Baltimore is one of the most mixed towns in the world. Straight and gay people hang out together and talk about everything. I love to hear stories about heterosexual sex – kinko heterosexuals and their wild nights.

Filmmaker: Pecker feels very much like a classic Hollywood comedy, like a Preston Sturges film. There are striking coincidences between Pecker and Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels. Each has two different worlds – one sophisticated and one not – being seen through each other and attempts to resolve their contradictions through art. You as well seem to live in two worlds with two careers as a filmmaker and an artist.

Waters: I go to great pains to keep those two very separate. In fact this is one of the few times I’ve talked about them in the same sentence. Partially I don’t want to seem that I use my film career to promote my art, although I choke on that word. It is history, not me, which can call something art. And while this work is based on my knowledge of film, and jokes about it, it is very separate. I would never do art interviews in People magazine. I try to keep them very different because I like the art world. I collect it, I go to openings, I am obsessed by it.

Filmmaker: The impulses that lead one to film production versus the impulses that lead one to art production are so different. What does each give you?

Waters: As I say in my book Director’s Cut, the impulses are the exact opposite. The film world has to play in Peoria; in the art world, if it plays in Peoria, it’s probably bad. No one in the art world ever tells you to dumb it up. It is a great relief to me to work in a medium that only has to appeal to a very small, intelligent group that respects wit.

Filmmaker: And how is it to work in such different modes of production – film being expensive, highly collaborative, constantly negotiated; art being less expensive, fairly insular, very specific?

Waters: To me it’s the same kind of obsession, only in different directions. Just as I keep notebooks for film ideas, I keep another set of notebooks for art work. I have a studio in Baltimore. When I work on my movies, I write them in my office at home. I keep these two lives very, very separate and think differently in each, but [the two forms of work are] still about what makes me smile. Even The Marks [a series of art photographs], which is somewhat serious, I guess, is really an example of the worst unit photograph ever. Everything that should be in a movie still is gone, except for the marks that the actors have to hit. It is unit photography in complete reverse because these photos can promote nothing. So that art work comes from the same input; it just goes in a completely different way.

Filmmaker: On the set, how do the remaining members of the "Dreamland players," the actors from your earlier films, relate to the Hollywood actors now featured in your films?

Waters: Basically it is understood by the ones still with me that we have to keep reinventing these things, keep reinventing our sense of humor with the times. If I made midnight movies now, that would be pretty stupid because they don’t have them any more. I remember the first day of rehearsals for Serial Mom. Kathleen Turner and Mink Stole were sitting on the couch in my living room calling each other "cocksucker." That moment was everything that I ever wanted. For me, casting is really just putting together a good dinner party.

Filmmaker: As an auteur, you’re an established cinematic figure with a cult following, but that doesn’t seem to have made the financing of your films any easier.

Waters: No, I had half the money that I had for Serial Mom, because this film was all union. No one has made a $6.5 million union film in Baltimore. And part of it is that Baltimore is no longer that cheap. Now there are these movies coming to Baltimore with $70 million budgets. So all these people who have worked for me in the past now have to take a pay cut to work with me.

Filmmaker It is somewhat sad that even though you have continually proven yourself you are not seen as bankable commodity.

Waters: I am in a way, but here is the one thing – if I wanted to be very rich I would just go and direct other people’s scripts. I would have no problem getting movies made. Any director who also writes the film is going to have a harder time getting the money because people can’t control it as much. But the problem is that I don’t know how to direct somebody else’s words. I would be bad at it. I think that I would be insecure. Because in my mind, I have played every character, done every action before shooting ever starts. I don’t know what you would do as a director if you didn’t write the script, except say "cut" or tell the actors to do another take. To me the fun of it is thinking it up and then making it real. That is what directing is for me, but thinking it up is a huge part of the process.

Filmmaker: Would you ever consider making a remake then?

Waters: Probably not, but if so, it couldn’t be a hit. I think that you should remake flops. Why would you remake something that works? Remake the ones that didn’t and fix them. And it’s cheaper – you could get the remake rights to Ice Castles for nothing. I would make a really bad movie that I loved and make it better.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →