BRIDES AND MONSTERS

Curtis Harrington revisits the past.

|  |  | |

|  |  |  |

Curtis Harrington in Usher.

In an old pink house at the lip of a "cul-de-sac," semi-high in the Hollywood Hills, there lives a haunted man. His name is Curtis Harrington – legendary filmmaker, pioneer film historian – and his legacy shrieks for itself.

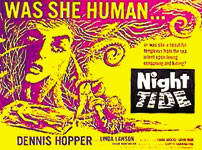

A founding figure of the second wave of the American avant garde (Maya Deren was a mentor, Kenneth Anger a one-time partner), Harrington was born in Hollywood – or somewhere just down the street. He wrote the first book-length study of Josef von Sternberg, directed warped horror-curios like Night Tide and Who Slew Auntie Roo?, and signed his name on more episodes of "Charlie’s Angels" than he ever cares to remember. (Only two, actually, but more than enough.) A close friend of director James Whale, Harrington served as an unofficial consultant on Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters, walked actor Ian McKellan through the director’s former mansion, and singlehandedly rescued Whale’s nearly-lost masterpiece, The Old Dark House, from certain oblivion in the depths of the Universal vault.

Now 72, Harrington has had the sort of career that could serve as a road map of Off-Hollywood – that gloriously ramshackle place where dimming stars and determined directors continue to toil beyond the tinsel, rarely touched by klieg lights but refusing to fade away. To be haunted, it seems, was his destiny. "I have a very macabre turn of mind," Harrington admits, "and there’s no way that can be explained. It’s just a leaning I’ve had since childhood, and I have it to this day."

History bears him out. In 1943, while Casablanca was winning an Oscar, Harrington, then 14, was making his first film, a version of Edgar Allan Poe’s "The Fall of the House of Usher." The story of Roderick and Madeline Usher, siblings doomed to follow each other into death’s maw, the film (never available to the public, extant only in Harrington’s personal collection) was uniquely cast: Harrington himself played both the brother and sister parts. Nearly 60 years later, Usher, the director’s new 36-minute featurette – an elaborate home movie with a professional veneer, shot mainly in Harrington’s little pink house – closes a circle. "I made Usher simply to make a film," he says, "just like I made the short films at the beginning of my career. It comes mainly from the intense personal relationship with the works of Poe that I’ve had for most of my life."

Like Usher’s mansion, Harrington’s own house has its fallen dimensions: delightfully gaudy, it’s filled with busts of the Medusa and ancient volumes on Alastair Crowley and hung with thick drapes and signed photographs of handsome gargoyles like Vincent Price. "It’s the closest thing we have in L.A. to the set from a Mario Bava movie," says Dennis Bartok, programmer for the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles and a longtime Harrington supporter. "Curtis’s films, too, are filled with ornate surface textures. They’re these wonderfully gothic combinations of lyricism and surrealism and poetry that remind you of films like Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet and Georges Franju’s Eyes without a Face."

In the ’40s, while still a teenager, Harrington made short psychodramas like Fragment of Seeking and hung around with Anger; together, they started "a small distribution thing" called Creative Film Associates and ran ads in The Partisan Review to promote their work. Deren, who had by then migrated to New York, was a personal friend: "I’d written her a letter after seeing Meshes of the Afternoon," he recalls. "She replied, and eventually we met. After that, whenever she’d come to Los Angeles I’d throw a little party for her and provide bongo drums so that she could dance. Maya loved to dance."

In the ’50s, Harrington played the part of Cesare the Somnambulist (reborn from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) in Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome and during the daylight hours worked as producer Jerry Wald’s assistant, on films such as Peyton Place. In the early ’60s, he made Night Tide, a film about a man’s (Dennis Hopper) love affair with a mermaid which Corman picked up for distribution a couple of years later; Corman hired him again, to direct Queen of Blood, a science fiction curio with Hopper and Basil Rathbone. A stranger double-bill on the subject of menstruation could never be made.

|

| Linda Lawson trapped beneath a pier in Night Tide as Dennis Hopper comes to the rescue. |

Harrington’s big break came in 1967, when Universal hired him to make Games, a creepy modern-day haunted-house flick starring James Caan and Simone Signoret. What’s the Matter with Helen? (with Debbie Reynolds, who considers the film her personal best) and Who Slew Auntie Roo? – both with Shelly Winters – quickly followed. Perverse and intensely personal films, all three fell victim to studio indifference, and Harrington’s mainstream career seemed to evaporate like the mist from a broken fog machine. Television paid his bills throughout the 1970s, where he worked on episodes of everything from "Baretta" to "Dynasty," collecting paychecks from Aaron Spelling but only rarely managing to apply his art: "Episodic television is so cut and dried – crap, really. I executed those assignments with the utmost dispatch."

What television – and a number of drive-in and video-bound oddities – did afford Harrington was the opportunity to work, and often to form friendships, with many of Hollywood’s legendary leading ladies. Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Collins, Piper Laurie, Ann Sothern, Ruth Roman and Agnes Moorehead – these are the brides of Harrington’s delightfully monstrous creations, and his camera adored them all. If he seemed to be channeling the spirit of Gloria Swanson’s faded glamour queen from Sunset Boulevard through every actress he ever cast, imagine the thrill he must have felt while working with the grand dame herself – on a 1974 made-for-television opus entitled "Killer Bees."

"Hollywood now is infinitely worse than it was 20 or 30 years ago," says Harrington, who remembers gazing, as a child, at the walls surrounding 20th Century Fox studios, and wondering what could possibly lurk inside. "At least there was a chance of getting something interesting made back then. Now there’s very little. The problem of my career, of course, is related to that. I made a series of films, and none of them were major hits. In retrospect, it’s easy to understand things from the executives’s perspective: ‘Harrington’s been up to bat a few times, his films haven’t made any money, so fuck him.’"

Harrington hasn’t directed a feature since 1985’s Mata Hari, produced by Menahem Golan and starring "international erotic icon" Sylvia Kristel, but he’s hardly lost in cinema’s past. "I still go to see films that interest me, and when I do, I look for the individual talent, always. I’ve made a great point of seeing Neil LaBute’s films, for example. Not my genre, but very, very interesting. You might guess who my favorite contemporary filmmaker is – David Lynch. I love Lost Highway, though I seem to be a party of one."

Usher is both the director's way of keeping in touch with his memories, and continuing to make art in the present; he financed it himself, with a little help from his friends. Cinematographer and longtime associate Gary Graver brought his own grip truck, Panavision provided a camera free of charge ("because of the artistic nature of the endeavor," Harrington says), and Roger Corman picked up the insurance coverage for a day's shooting in Rosedale Cemetery. The film itself abounds with nods to the director's formative influences: a reference to a favorite French poet (Pierre Reverdy), a line from Poe's "The Conqueror Worm," a quote from Whale's The Old Dark House. Harrington himself, complete with Poe's distinguishing mustache and bow tie, plays Roderick Usher. Madeline – in a long-awaited return to the screen – is played by the legendary "?". Last seen in James Whale's The Bride of Frankenstein (the greatest of the Universal horror classics), "?" hasn't performed in eons, but, as Harrington says, "you'll know her when you see her." He insists, however, that Usher isn't simply about its star. "It's about twins who must remain forever psychically joined. As I have Roderick put it the film, they 'share the same soul.' A bit obvious, I know," Harrington admits with a grin, "Poe with a megaphone."

In a sense, though, the impulse to broaden poetic meaning in order to reach the masses has been an aspect of this experimentalist-gone-mainstream director’s filmmaking all along. And he’s spelled it out before. In the 1976 possession-thriller Ruby, for example – a film about a haunted drive-in that Harrington started but wasn’t allowed to complete – a para-psychologist and part-time exorcist babbles on about "somnambulistic states" until Stuart Whitman finally stops him with a growl, "C’mon, doc, don’t give me those 10-dollar words. Just tell me what the hell is going on around here?!"

Usher, never mind the megaphone, shows ample evidence of the strange and the sublime: disarming close-ups of agonized longing, a ghoul from beyond the grave dressed in a Victorian nightgown, and Harrington himself locked in death’s embrace. But it’s far from the garish excess of the Poe mutations that Corman and Vincent Price once wrought together. It’s closer, in fact, to the deeply personal psychodramas Harrington once forged – from myth and madness – in the dark recesses of his career. "What I wanted to do with Usher," he says, "was to make a film about art and death. That’s why I decided to embellish Poe’s story in certain ways, by turning Roderick into a poet, for example. For me, poetry is a metaphor for art in general."

More than just metaphor, poetry is the stuff of dreams and nightmares, at once concrete and illusory, slight as wafting silk, thick as handmade bricks. And those bricks are the very stuff from which every weird and wonderful flourish the director’s long, remarkable career was fashioned; the firmament of filmmaker extraordinaire Curtis Harrington’s vast and haunted house. – Chuck Stephens

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →