IN PRINT

Jim McKay talks with Ray Carney about John Cassavetes

I have a confession to make. About seven or eight years ago, I came upon a very early, bootleg copy of a book of interviews and commentary called Cassavetes on Cassavetes. It was about 100 pages long and was a Xerox of a Xerox of a Xerox, but in its pages I found some of the most inspiring thoughts about film, art and life that I’d ever read. It quickly became the most important book on my shelf.

Confession number two is that the book meant so much to me that I Xeroxed the Xerox and gave it out to fellow believers a number of times. I didn’t know if the book would ever find a publisher, and, in the meantime, how could I keep this crucial information (both practical and spiritual) from others?

In the end, I think it’ll work out fine. The book has finally been published and, at over 500 pages, is so much more jam-packed with material I’m certain that everyone who got the bootleg from me will run out and buy the official version.

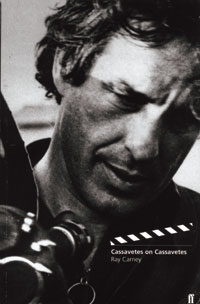

Over the course of shooting two features (Girls Town and Our Song) and producing half a dozen others, Ray Carney’s Cassavetes on Cassavetes (Faber and Faber, Inc., $25, paperback, 544 pages) sat by my bedside like a bible. Late at night, while obsessing over some concern about tomorrow’s shoot, or the next day’s credit-card bill, or an upcoming meeting with a distributor, I’d open up the book to a random page and read. Just a passage or a page, it never took much. In those pages, I found the strength, support and spirit to go on. Sound a bit over-dramatic? Well, if you’re a filmmaker or a film fan interested in cinema outside the Hollywood system, pick up the book for yourself and start reading. You’ll see.

Over a period of a few weeks, I engaged in an e-mail conversation with Carney, a professor of film at Boston University who maintains a Web site devoted to independent film at cassavetes.com. We talked about independent film and the influence of John Cassavetes’s work.

JIM MCKAY: You have three new books out about John Cassavetes: a pocket guide to his films, a BFI text on Shadows, and Cassavetes on Cassavetes. They all took a very long time to find their way to the bookstores. Talk about that journey.

RAY CARNEY: One of the reasons there are so few really good books about real indies is because the film-book business is not that different from the movie business. Book proposals are judged in terms of their “box-office potential.” An indie writer has to overcome obstacles, adapt to circumstances, take chances and pay the price — in emotions and dollars — just like an indie filmmaker. You might think academic presses would be less commercially driven than the trade houses, but they’re even worse. Every book has to be approved by a committee of film professors, who are always the last to know anything new about film and are complete fashion slaves to media-created trends and fads. In a nutshell, getting anything into print about Cassavetes was a struggle.

Cassavetes on Cassavetes marks an era in my life, something like 10 or 15 years of work. The origin was a series of conversations I had with Cassavetes in the final decade of his life. He said so many wonderful things, I thought it would have been a shame to keep them to myself and not share them with the world. The book is his own personal account of how he made his movies — from the scripting, fund-raising and planning, to assembling the crew, struggling to get the films into theaters and interacting with the press. I thought it was unbelievably great stuff, but it was a hard sell. I spent years trying to persuade a publisher to print it. One after another told me that Cassavetes just wasn’t a big enough name. I remember one editor saying, “Well, if it were only Woody Allen or Oliver Stone, it would be different.” It was frustrating, but now I realize the delay was actually a great thing, because every time the manuscript was rejected, I re-wrote it. The longer I carried it around, the longer and better it got. Years went by, and I was almost at the point of self-publishing it when an editor at Faber and Faber phoned me out of the blue, said he’d heard about it, and asked if it was still available. By that time it had become much more than the personal story of Cassavetes’s life. It became an account of the predicament of every independent artist trying to do something different, something a little out of the mainstream.

The book portrays, I think for the first time ever, what it’s really like to be an independent filmmaker in our celebrity-obsessed, profit-driven culture. It shows the work it takes to make a film on your own: the re-writes, delays and changes of plans; the setbacks at the distribution end; and the unbelievable stupidity of newspaper and television reviewers who hold your fate in their hands. It uses Cassavetes’s life and work to tell the story of the resistance every real artist faces in our happy-face, entertainment-obsessed, Hollywood-addled culture.

MCKAY: One of the things I love about the book is that Cassavetes is one of those great, very misunderstood/misinterpreted people in history (probably in part because he lived and worked at a time when every filmmaker wasn’t being interviewed/documented/and Web-sited to death). And the book, by revealing so many deep thoughts directly from the source itself, is as wonderfully frustrating and non-pat as his films are. It reveals him as a very contradictory character, full of flaws and contradictions, but ultimately as a man with a big heart and a humanism resulting from curiosity, hard-headedness and a dedication to seeking out the truth.

CARNEY: Cassavetes was a bundle of contradictions. He was pig-headed and sensitive; willful and responsive; self-centered and generous; serious and a clown. I think that’s why he was able to create characters who had so many different sides, and why he was able to appreciate their all-too-human foibles. He had the same amazingly nonjudgmental stance toward them that he had toward himself. That’s what makes his presentation of his characters so different from the scorn and condescension that Altman or the Coen brothers display toward their characters’s limitations. Look at Ben in Shadows, McCarthy in Faces, or the three men in Husbands: They’re pretty imperfect human beings, but Cassavetes loves them, warts and all.

MCKAY: There’s a new posse of film guys whose work, maybe because it seems to be about “real people,” maybe because some people see it as “raw” or “emotional,” has been compared to Cassavetes. I’m thinking of people like Neil LaBute, Sam Mendes, Todd Solondz, and so on. Do you think the comparison is justified?

CARNEY: It comes out of a misunderstanding of Cassavetes’s work. Compared to the sentimentality of Hollywood, Cassavetes’s films may seem to be disillusioned and cynical. But they’re not. They’re tough-minded — but upbeat, even hopeful. That’s why when I leave his films, no matter how difficult things may be for Mabel or Sarah, or how sad their lives may seem, I don’t feel depressed but elated. The characters are so passionate, so alive. They show me how strong we are. They make me feel that we can survive anything, and that almost anything is possible. They don’t make me want to despair or give up, but to believe in life again. That’s the opposite of films like Happiness, Your Friends and Neighbors and American Beauty. They are about doing dirt on life, which is why they have more in common with Altman than Cassavetes.

Look, life is life, and it’s not a Hollywood movie. It’s messy, confusing, imperfect, and often difficult and disappointing. That’s a fact. But what matters — in life and in art — is what you do with that fact, what your response is, how you cope with it. LaBute, Solondz and Mendes represent a fundamentally adolescent response. They want us to be shocked by all these dirty secrets they reveal: “Oh my God! You mean not all people are nice? And parents can be as messed up as their kids? That’s horrible. How can I go on?” It’s a teenage view of life — shock and dismay followed by sardonicism, irony, mockery, black comedy and gallows humor. We all went through it for a few months when we were 18 years old. But Cassavetes’s work figures an adult perspective: “OK. People are not perfect. They have good intentions but hurt each other awfully anyway. They will never really understand other peoples’ points of view. Now that we know that, how can we still go on together? How can we find a way to love life and appreciate each other anyway?” And then, miracle of miracles, he shows us! That’s great art, not teenage angst and nostalgia for our lost innocence.

MCKAY: The greatest myth about Cassavetes is that his films were improvised. If this is, indeed, a myth, how would you describe his relationship with his actors and their input into the material? And how did his method (or lack of one) change from film to film?

CARNEY: Beyond a few scenes in Shadows and brief moments in the later movies — but no more than you’d find in any other film — everything was scripted. I have the shooting scripts in my file cabinets to prove it! When it comes to Gena Rowlands, she’s not an improvisational actress. She won’t work without a script, so improvising was not an option in the films she acted in.

What misleads people is the edginess, freshness and passion of the performances. Cassavetes got the effect in different ways. First, he avoided the “pretty writing” syndrome that most screenplays fall victim to. Cassavetes worked, as he once put it, “to get the literary quality out.” He wrote dialogue that sounds the way people really talk —loopy, forgetful, distracted, aimless. In other movies characters sound like they not only know what their problems are, but what the solutions are. The verbal confusion and sprawl captures the emotional confusion and sprawl of life, where things are never emotionally clear. We almost never say exactly what we mean or mean exactly what we say. We talk for a million reasons that are different from what we say: to cheer ourselves up, to convince someone to love us, or to impress someone. The apparent aimlessness of Cassavetes’s dialogue captures those subtextual swirls and crosscurrents. Truth is under the surface.

MCKAY: There are some filmmakers working today who attempt to do the same thing, but when it’s obvious and not well-done, it comes off just as stagey and cute as the other style of writing.

CARNEY: Clichés are always waiting to trap us — in life and in art. I’ve seen dozens of indie movies where pretty-boy New York actors pretend to be someone else, and the more they pretend, the more they sound like New York actors pretending. One thing Cassavetes used to say to his actors was, “All you have to do is not pretend.” Pretend emotion isn’t good enough; it has to be real emotion. You have to kill the actor to really act. Cassavetes had to force his actors to put down their bags of actorly tricks to get any real acting out of them. He was all over Peter Falk throughout Husbands and A Woman under the Influence not to do any of those “cute” gestures and facial expressions that Falk is so great at. In Faces, he had to reign in Seymour Cassel and keep him from mugging and clowning his way through his role. Look at the performances of Cassavetes’s actors in movies by other directors and you’ll see what happens when they’re not reigned in. They can be pretty awful.

Another way Cassavetes got the impression of spontaneity was by minimizing rehearsal and encouraging the actors to experiment with different ways of playing each take. Much of what you see happening in his films that feels like it is happening for the first time actually is happening for the first time for the actors. Nick Longhetti’s wonderful confusion and clumsiness in A Woman under the Influence is Falk’s real confusion and real awkwardness as scenes were being shot. They hadn’t been all blocked out in advance, or hadn’t had their mystery explained away by the script or the director. On top of that, Cassavetes forced the acting to be even more spontaneous by calling out re-directions in the middle of a take, then removing his voice from the soundtrack in post: “Get the hell out of the way.... Go over there! No, don’t look at her! Stop right there. Take a breath....” If Falk looks bewildered, it’s because he was.

Cassavetes would also do something else that you couldn’t get away with if you weren’t working with your family and close friends. He’d push actors’ buttons — especially Gena Rowlands’s — to get them into a particular emotional place that forced them out of their comfort zones. He’d throw tantrums between takes, yell, make faces or obscene noises while they were performing.

MCKAY: So if it wasn’t script improv, sometimes it was emotional improv.

CARNEY: Right. But that’s the most important kind of improvisation. Creating new dialogue lines is trivial; discovering new emotional lines through a scene is what it’s all about. But that puts the burden on the actor to come in armed for bear. You can’t phone in your performance. You can’t ham around and showboat like Nick Cage or Jack Nicholson. You have to really look, and listen, and respond to the situation and people around you, alive in the moment. You have to really risk something and expose yourself.

MCKAY: I happen to believe that, in some ways, no work is “apolitical.” Its maker may insist that its intent was not political, but even a film like E.T., in the way that it interprets our society, and in the ramifications it has on its audience, is political. On the surface, because Cassavetes’s work is so “personal,” I think there’s an instinct to think it’s apolitical. Yet it explored situations of class and race in ways that very few American filmmakers’ works have.

CARNEY: The opposite is also true. Lots of explicitly political movies, all those Academy Award nominees that wear their social consciences on their sleeves, from Silkwood to Erin Brockovich, are actually the real escapist works, because they locate our problems outside ourselves. They tell us that that the enemy is someone else, some “them,” “out there.” Their hell always has other people in it. That’s just too easy. It’s cowboys versus the Indians one more time. That’s why Spielberg is a cowardly filmmaker. He never shows us what is wrong with us. Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan let us blame someone else as much as Jaws does.

If you construe politics broadly, as in how the individual defines his or her identity and interacts with others, every movie is political, whether it intends to be or not. We have this primitive notion of what constitutes “engaged” filmmaking. We count the number of minority figures in the cast or wait for a big speech about power, race and class. It got us by in high school when we were electing the student government, but it has nothing to do with art. How you organize your narrative is a political statement. How you define your characters’ identities is a political statement. How you photograph them is a political statement. Look at Leni Riefenstahl if you need proof of that. Look at Faces, the way Cassavetes’s camera lingers on the frightened faces of the women during the scene in which they come back to the house together, and the way he allows Florence, the oldest woman, to express her sexual needs. It represents deep “feminist” statements. Cassavetes’s presentation of Richard’s and McCarthy’s ways of interacting in Faces and his exploration of Cosmo’s need to look and be “cool” in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is a deeper critique of masculine ways of being than anything I’ve ever read about the “men’s movement.” The color-blindness of Shadows’s narrative — which dramatizes a racial incident but then goes on to demonstrate that a character’s race is not the most important thing about his or her identity, represents a far more radical statement than anything in Malcolm X. The photographic equality of the characters’s treatment in Shadows and in Minnie and Moskowitz, with the minor figures being given as much time and emotional importance on screen as the nominal “stars,” represents a profound insight into the way the Hollywood star-system skews our understanding of life.

Almost all Hollywood narratives are organized in terms of the mythology of late-20th-century capitalism. Given their financing, it is not really surprising that they should embody the values of Wall Street — “starring,” wily individualism, competition as a way to get ahead, and belief in external actions as the solution to problems. You are what you do, and who you subdue, in these films. Life is about outsmarting others.

Cassavetes critiques those myths, not by having characters give Capraesque speeches, but with the shape of his narrative and the way he shoots and edits. Faces’s narrative shows what business values do to us emotionally and socially. It shows that care and responsiveness matter more than domination and control. Its characters’ identities are not individualistic, but relational. It offers inward and spiritual ways of understanding. Characters are defined not in terms of what they do, but what they are.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →