IDENTITY CRISIS

Hollywood scripter Henry Bean’s directorial debut, The Believer is a bracing and intelligent drama about a Jewish neo-Nazi. Josh Zeman talks with Bean about Hollywood phone culture, distribution nightmares and religious paradoxes.

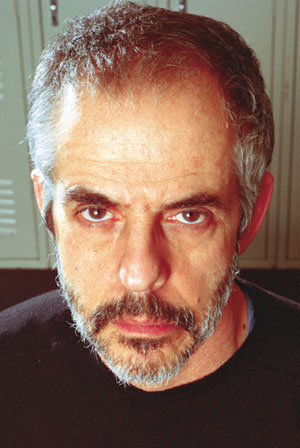

Henry Bean photographed by Richard Kern.

For over three decades, independent filmmakers have pushed the limits of depicting sex and violence on screen, shocking their audiences with visceral and stark interpretations of acts and desires once deemed unfit for popular consumption. But in doing so, independent film has created a new status quo; audiences have become jaded to these once-shocking scenes.

But even in this button-pushing environment, there is one subject that most independents are truly reluctant to tackle: religion. Few filmmakers are willing to critically examine faith and, maybe more importantly, the masses that hold it sacred.

Screenwriter-turned-director Henry Bean, however, has done just that in The Believer, an unsettling film that grapples with the complexities and contradictions of the Jewish religion and doesn’t let go. The film — the story of a violent young man who joins a neo-Nazi group and both struggles with and hides his Judaism — is something of a test of faith itself, forcing audiences to wrestle with the relationships between their own beliefs and the modern world.

Bean, best known as a top-shelf Hollywood screenwriter (Internal Affairs and Deep Cover), invested his own funds to get The Believer made on a low budget. His own belief in his script paid off — the film won the Grand Prize at Sundance and made a star of lead Ryan Gosling. Despite critical acclaim, the film struggled to get distribution before being picked up by Showtime for a fall premiere —postponed indefinitely at press time due to a sensitivity over some of the film’s content in the wake of 9/11 — and IDP for a theatrical run this winter.

FILMMAKER: Most of our readers are young filmmakers who, whether they admit it or not, are looking to make it into the establishment.

HENRY BEAN: They want to go Hollywood.

FILMMAKER: They think that somehow they’re going to be the ones who “break the rules” when they hit the establishment. You however, have been in “the establishment” and then left.

BEAN: I didn’t leave.

FILMMAKER: For this film, let’s say.

BEAN: And I’ll come back and do another film like this one, because I don’t feel like I can [direct] those other types of films — the regular Hollywood ones. I don’t think I could direct a good genre film. You know, the visual palette is not what I am good at. I’m good at writing these offbeat little things and figuring out how to make them. I couldn’t handle the corporateness of Hollywood. I can barely handle it as a writer. I don’t think it was always that way. Hollywood was started by guys who sold newspapers on street corners, and then they were making movies because it was a low-capitalization business. It isn’t that anymore — it’s huge, and it’s corporate. And there’s a natural conflict between the personalities of the people who want to make movies and the personalities of the people who want to run a corporation. Every now and then you get somebody who’s in between, but the two cultures don’t naturally go together.

|

| Billy Zane and Theresa Russell in The Believer. Photo: Liz Hedges. |

FILMMAKER: So how did you wind up becoming a successful Hollywood screenwriter-turned-independent filmmaker?

BEAN: I started out writing novels. I wrote and published a novel a long time ago. It was pretty good, but I saw that the market — that is, the audience — for my novel was 10,000 people. And I didn’t just want to be talking only to those people. When I thought about movies, the movies I thought about were much bigger and more open and addressed more people but in many ways had the same concerns [as my fiction]. I always loved movies, so I started writing them. This was the late ’70s, and Hollywood was a very open town. You went to Hollywood and called up relatively big people; they had no idea who you were, but they’d call you back. And when they called you back, it made you feel like, “Oh yeah, I can do this.” You know, I’d been in my room for three years writing a novel, so going out [to L.A.] and making phone calls, and getting return phone calls was a great escape.

FILMMAKER: It’s pretty amazing how much more complicated the culture of the phone is in Hollywood now — that phone-list bullshit. The assistants say, “Oh, you’re on his phone list.” If you’re the first call after lunch, that means something. If you’re the second call in the morning, that means something else. And if you’re the last call of the day, that means something different entirely.

BEAN: That sounds so much like the petty little preferences and treatments that obsessed people in 19th-century Russian novels — all those bureaucrats. You know, the guys who formed the Hollywood studios had either been born in, or had parents who were born in, Russia. But the other thing is, when you go to Hollywood and they return your phone calls, and then, God willing, they hire you, you know you’re not really part of “the club,” but at least you’re in the game. It’s like when you were a kid, and you watched the basketball game from the side of the playground. Then, you got older, you got into the basketball game, and you looked at all the other kids standing on the side watching and thought, “Wow, I went from there to here.” Hollywood can give you that sense of accomplishment almost without paying you anything. It’s very powerful — and very seductive. People return your calls, give you passes to drive on the lot.

FILMMAKER: They build a culture for you.

BEAN: It’s not conscious. It’s not like the CIA or Trilateral Commission is in there plotting it. It’s a natural thing. You may not have really done anything, but you feel part of this thing, and it’s so reassuring. I think it’s much harder to be out here in New York City on your own. For all of the Independent Feature Project and everything else, you don’t feel the structure of a community here the way you do in L.A. But that’s a function of the fact that there’s so much less bullshit here. All this stuff we’re talking about is the bullshit, but it keeps you happy. It keeps you feeling like something’s happening when nothing, in fact, is happening. Here, if nothing’s happening you really know it. In New York City, working is what bonds people together.

FILMMAKER: So what made you decide to make The Believer?

BEAN: What happened was, I was always writing spec scripts, sometimes big, sometimes small, and never getting them made. I always had in the back of my mind the script for The Believer. A friend of mine, a guy I’ve known since I was a kid in elementary school, teaches film at Queens College, and he said, “Give me one of your old scripts so my students can film a few scenes out of it.” Instead, I wrote a few scenes from The Believer and ended up directing them into a little short with his students. And I thought, this isn’t bad. After that, I wrote the feature.

FILMMAKER: What year was this?

BEAN: This was 1997 or ’98. I wrote it, and then a little production company which had a lot of money contacted me and said, “We want to make this.”

FILMMAKER: How did they find out about it?

BEAN: From my agent. You know, I’m an established writer. If there’s a new script by me, some people will read it. And they loved it. I was going to make it with them for $2.5 million. As soon as we started casting, they started to panic. The people who were [in charge of] selling the film said, “This thing is so hard to sell, we’re going to have to cast the biggest name we can get in every role.” And I said, “You mean regardless of whether they’re good for the role or not?” They said, “Do you want to get your movie made?” I was really convinced that they were right, so we went through these casting sessions, and I saw a lot of actors who were great, but I didn’t see anybody who I thought was right for my main part. There was one big name who wanted to do it, but who wasn’t right. I said, “Okay, let’s do it with him,” when I should have said I couldn’t do it. Then I panicked and said, “I can’t do it with him.” [The producers and I] had a big fight, and in the end I decided not to make it with them.

I was terrified that what I was really doing was avoiding the problem of having to make the film, so I called Peter Hoffman, who had been the chief financial officer at Carolco and now has a company called Seven Arts. I knew him because I’d worked with him and with his wife, Susan, who is Barbet Schroeder’s producing partner. I said, “Peter, I want to make this film for $1 million. If I put up half, will you put up the other half?” He laughed and said okay. When it ballooned up to $1.5 million, he got the additional money.

FILMMAKER: How did Ryan Gosling come into play?

BEAN: I saw 50 or 60 guys in New York City, then I went out to L.A. for a week and saw 100 more guys, Ryan was the last one who came in. He looked like a surfer — he had this knit cap and all this blond hair sticking out. He gave a reading that was very intelligent and idiosyncratic. The kid’s a genius. It was like he really was “the guy.” He had a couple of credits, but he was nobody, he was unheard of.

FILMMAKER: He was in the New Mickey Mouse Club.

BEAN: I didn’t know that at the time.

FILMMAKER: What did you think about him not being Jewish?

|

| Ryan Gosling and Joshua Harto in The Believer. Photo: Liz Hedges. |

BEAN: It was very scary. I thought at the beginning that I had to have a Jewish actor. Here’s the problem: I knew the perfect Jewish guy, not a Jewish Nazi, of course, but very Jewish, Orthodox, and a tough street kid. He was perfect, except he couldn’t act. And I needed an actor. When I went to L.A., it was clear that the Jewish actors didn’t bring me anything that the gentile actors didn’t bring. When I saw Ryan, Alex Alvarez, my costumer, said [casting him would] work. You cut his hair, you dye it, and his face doesn’t read that goyish anymore. As soon as Ryan came to New York City, I put him with the tough Orthodox kid, and he started imitating his mannerisms and speech patterns.

My biggest fear with Ryan was that he was going to be too nice, too sympathetic. As I was watching the film being made, I kept saying to myself, he’s too nice. When the film was all put together, I think he had a much shrewder and more accurate calculation of what was needed than I had. If he had been the way I wanted, the film wouldn’t have worked. One of the great things about this guy is that he can do the most horrible things in the world and you like him anyway. He’s an utter charmer. So when he’s beating the shit out of that kid, you also feel the anger that he’s feeling about having to do this, and it’s just frightening.

FILMMAKER: How did you come up with story itself?

BEAN: I had known about the historical incident at the origin of it. In 1965 the New York Times got a tip that a kid who had been arrested at a Ku Klux Klan demonstration in the Bronx — and who before that had been a fairly high-ranking member of the American Nazi Party — was Jewish. They sent a reporter out to interview him — similar to the scene I have in the movie. And the kid had a very articulate, well worked out anti-Semitic argument. The reporter said to him, “How can you believe all this when you’re Jewish youself.” And he said, “I’m not Jewish.” The reporter had evidence. And the kid said, “You print that, and I’ll kill you, and I’ll kill myself.” They printed it that Sunday, and he killed himself within an hour of seeing the paper. The New York Times got a lot of grief about this.

Arthur Gelb and Abe Rosenthal wrote a book about this kid called One More Victim, and the book traces how he went from being the good Bar Mitzvah student in Hebrew school to a neo-Nazi. The thing that was interesting was that while he was a member of the American Nazi Party, and supposedly hiding his religion, he’d bring knishes back to the Nazi headquarters. So, this idea of somebody who is hiding something but giving it away, that’s really where [the film] began. But it evolved a lot.

One day Mark Jacobson, who wrote the story with me, and I were talking, and I had the idea for the scene halfway through, where Ryan goes into the synagogue. That opened up the possibility of the second half of the movie, where [Ryan’s character] becomes a Jew and a Nazi, where he’s leading a double life. I was so electrified — I’d been looking all my life for this idea. I never felt like a Nazi, but I always felt myself pulled between extremes, radically opposing thoughts or emotional states.

FILMMAKER: Screenwriters are taught that conflict, and usually external conflict, produces drama.

BEAN: I’m drawn to a conflict that’s internal, that’s within a character, and not between characters. One of the problems I’ve had in Hollywood is either an inability or lack of interest in externalizing that conflict and embodying it in different characters.

FILMMAKER: Deep Cover and Internal Affairs, two films you’ve written, suggest there are two forces at work within a character. This then extends to The Believer as well. The protagonist couldn’t be any more “undercover” than as a Nazi.

BEAN: That’s why I have to go in another direction — two is not enough. I should go for three or four! I do think we tend to get too dualistic, too “either/or” when really there’s a multiplicity of choices.

FILMMAKER: Maybe this duality is the only way you can present these themes to a goyish audience to help them understand the subtleties of the issue.

BEAN: That’s a good point. My wife’s son, the novelist Paul Hond, said, “This isn’t a movie about a Jewish Nazi, this is a movie about being Jewish.” This is what it feels like, this crazy mishegas, this overblown stuff — that’s the way Jews hyper-dramatize their lives.

FILMMAKER: Did you research a lot?

BEAN: I read a lot. And I went out to some bars in Queens where I ran into white supremacists who were so pathetically stupid that I had to invent Theresa Russell and Billy Zane’s characters. I thought, if I didn’t give this world [of white neo-Nazism] some sense of respectability, there was no way it could balance against the Jewish world. So I had to make it bigger and better than it was.

FILMMAKER: As a fledgling screenwriter, I’m continually researching my main character, finding out everything about him. I think in some ways I kill my ability to create by researching too much.

BEAN: I think you can research too much, but I think some research is very, very good. You write from within yourself, but research takes you out of yourself, so you can return to yourself almost without realizing it. If you are imagining what you feel like, you can get blocked. But if you’re imagining what a girl from Canarsie feels, you’re still thinking about what you feel. But you ‘re coming at it from this weird direction that makes you lose the self-consciousness.

FILMMAKER: So how much were you able to take from the real character, other than that initial concept?

BEAN: The real character is really an unfortunate guy — homely, very thwarted, nerdy, unappealing and just riddled with self-hatred. It was the complexity I was interested in, but it wasn’t as manifest [in real life] as it is in the film.

FILMMAKER: Were you learning about Judaism as a connection? Or was it just a hobby?

BEAN: I certainly wasn’t doing it for the sake of the film. I was doing it because I was feeling it. You know, I grew up in a Reform home, and I was Bar Mitzvahed in this incredibly rinky-dink setting — I didn’t know anything. My wife is the daughter of a conservative rabbi. She’s fluent in Hebrew and all that. I really got off on her explaining things to me about [Judaism], and I started to learn more about it. I have a kosher home now. I was drawn to the stuff. Avalon Books is publishing the screenplay with some other essays, and one of the essays is mine, and I write about my progression.

FILMMAKER: How did your screenwriting career prepare you to direct, or did it hinder you?

BEAN: It was my screenwriting career that caused me to structure this thing like a thriller and give it a kind of narrative drive that it might not have had otherwise. When I produced Deep Cover I was on the set every day. But it didn’t prepare me enough. Watching other people do it is very different from actually doing it. I wish I had had stronger visual ideas.

FILMMAKER: You brought on a very good d.p., Jim Denault.

BEAN: Jim Denault is as important to this film as anybody. His work is beautiful, and yet it isn’t pretty. He’s after a deeper kind of beauty. He has a tremendous gift for storytelling, and he’s very perceptive about performance. When you watch six takes of the same shot, you watch how his movements get more and more responsive to the performances.

FILMMAKER: How did you and Jim arrive at the film’s visual style?

BEAN: [The Dardenne brothers’] La Promesse is a big reference. I had seen it, but Jim suggested that we design the film somewhat like La Promesse, with a lot of handheld camera — a quasi-documentary feel. Since we had 29 days to make a film that had a lot of locations and a lot of speaking parts, we didn’t feel we had time for elaborate coverage or lighting setups. That was one of the concerns. We picked the 7289 [Kodak] stock film because it required much less lighting in low light. It’s given us a very grainy look, at times grainier than I would like, but it’s still okay. We shot in Super 16, and I think that, if we re-blowup, we’re going to solve some of that graininess.

FILMMAKER: What was your biggest concern during shooting?

BEAN: I thought about performance a lot, and I thought about telling the story. But I was a mess, a wreck. The first morning I woke up and thought, “Yesterday I had the camera here, I should have put it there — I’ve ruined the film.” And the next day I woke up with a new way I’d ruined the film. Every day was like that. But I’m friends with [director] Chantal Akerman, and in the middle of the film, I spoke to her. She said, “Just do one thing in each scene. You’ll get other things, but just think about one thing.” So I tried to be simpler. As time went on, I began to know what I wanted to get out of a scene.

My favorite scene in the film — because I felt like I really designed it — is the one where Ryan goes back to shul for the first time on Rosh Hashanah and he has that argument with his friend outside the door, I was really going for the His Girl Friday thing. You know, the film is all talk, and to me talk is all about interruption. One thing that drove me crazy was the sound guys telling me you can’t have people step on each other’s lines. They said, “You can create that in editing.” But you can’t. So finally in that scene I shot as much of it in the master as possible so I could have the interruptions. Since it’s a multi-part argument, I rehearsed it until the actors really got it down. And that scene I loved.

FILMMAKER: You’re doing what Mamet would do.

BEAN: Well, Howard Hawks is my model more than Mamet. His Girl Friday, I love that film. When I was working on The Believer, I began to realize that American talking comedies are a huge influence on me. I always knew I liked them, but I realized that in many ways I was trying to do [what they do].

FILMMAKER: How do you characterize your distribution experience?

BEAN: Disappointing. It’s disappointing to win Sundance and not get the “big deal” from a major distributor. We went to Sundance and thought, “God, what are people going to think of this?” People liked it. Nobody seemed to think it was an anti-Semitic or reprehensible film. And so we thought our anxieties were misplaced: People see the good intentions of the film. I left Sundance and went to L.A. to work on a job there, and somebody said, “The Wiesenthal Center wants to see this thing.” I thought, oh well, the Wiesenthal Center will like it like everybody else liked it — as if Sundance were really a cross section of the world! I didn’t know that the Wiesenthal Center was so politically conservative. I walked into the room to introduce the film, but the minute I looked at Rabbi Abraham Cooper, I knew I’d made a mistake. If I’d had my wits about me, I probably would have picked up the tape and walked out.

FILMMAKER: How did you know?

BEAN: He had that look. I’ve seen a lot of rabbis like this. They don’t like people like me.

FILMMAKER: What are you that he didn’t like?

BEAN: I’m not obedient. I’m not a good boy. They want to know, are you here to serve the process, to fit in, or are you here with your own agenda? If you’re here with your own agenda, they don’t like you. I didn’t come in thinking I had my own agenda, so the rabbi knew me better in that sense than I knew myself. “I made this film, and it’s my offering to the Jewish people.” He didn’t want to hear it.

FILMMAKER: What was his reaction after you screened it?

BEAN: I wasn’t there because I wasn’t allowed to be there, but he was quoted to me as having said, “The film does not work, there is no redemption, and it’s a primer for anti-Semitism.” So after that, we said, “We’ve got to do something to balance this.” So we went to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), just to get another Jewish organization weighing in. The ADL’s reaction was, “Well, we don’t know about this thing, but we see what you’re trying to do, and we’re okay with it.” If I had gone to the ADL first, maybe it would have been different.

FILMMAKER: So what happened in L.A. after Sundance?

BEAN: Sony Picture Classics, Paramount Classics, USA — there were a number of places we were talking to, and then they all disappeared. Well, Paramount Classics strung us along, even after the Wiesenthal thing. They refused to say no. I felt that, even before the Wiesenthal thing, Paramount Classics was going to say no. They were nervous. I think they felt they could make money on the film, but that it was going to endanger their more important products. Nobody wanted to be in the position of Lou Wasserman having the Christians picket outside his house for The Last Temptation of Christ. So that’s what I think did it. They just don’t return your calls.

FILMMAKER: Do you think that the reason the film did not get a big deal was a question of finances or censorship?

BEAN: I don’t think it was finances. The [marketing executive] at Paramount Classics said to me, “I can market the hell out of this thing.” So why can’t they do it? Well, because her bosses were telling her not to. I think they were telling her not to because they didn’t want their corporate name besmirched by what might be bad reaction from Jewish organizations. [The executives were] functioning as corporate officers. They’re saying, “Can this possibly hurt the studio?” “Yes.” “Is the damage it can do greater or less than the good it might do?” “Greater.” “Forget it then.” But there’s an irony. Who owns Paramount? Viacom. Who owns Showtime? Viacom. So, maybe I’m wrong.

FILMMAKER: Were there other people lined up?

BEAN: There were littler places that would have done it, but they wouldn’t give us any money. Showtime gave us $1 million. And $1 million meant we were going to [get our investment back].

FILMMAKER: So you did have other people who wanted to release the film theatrically?

BEAN: Look, I would call those people up and say, “How much money do you think we can make if you release the film?” And they would say, “I think we can make $400,000 to $500,000.” I was like, “Whoa!” Eamonn Bowles, when the Shooting Gallery was still there, was going to handle it post-Showtime. One time I called him up and said, “Eamonn, what if we blow off Showtime and you open the film?” He said, “I wouldn’t do that. I think you’d do better going with Showtime.” Well, when the guy you want to tell you to be crazy, to talk you into doing some crazy thing, won’t talk you into it…

FILMMAKER: Are you happy with the deal?

BEAN: I’m thrilled with the deal. The money is fantastic, I’m going to get more viewers from Showtime than I ever would have had theatrically. Best of all, I’m going to get viewers that I never would have gotten, people never would have gone to their local theater. These guys [at Showtime] like the film, and they understand it. They’ve been wonderful.

FILMMAKER: I read that you said, “All the people who are Jewish the way I’m Jewish will get the film.”

BEAN: That’s almost a tautology right there.

FILMMAKER: Were you worried that people who weren’t Jewish or schooled in Judaica wouldn’t get the film?

BEAN: I wasn’t worried about the gentiles. I was worried about Jews who would be offended. I was worried about that kind of Jewish Stalinism, in which there are certain things you don’t say whether they’re true or not because the enemy might use them against you.

FILMMAKER: So religion is the last taboo left in film?

BEAN: It may be. I don’t know if it’s the last. I’m looking for a new taboo for the next film.

FILMMAKER: Like Todd Solondz?

BEAN: Yeah, but I’m looking in different places. I don’t think I’m looking where he’s looking. I’m not doing that sex or disgusting interpersonal stuff. There’s another taboo that’s more severe.

FILMMAKER: Which is?

BEAN: I think you can accurately define power and seriously propose an alternative to power. Then I think you really have hit something. What Abraham Cooper at the Wiesenthal Center wasn’t defending was piety or what’s good for the Jews. What he was really defending was their power to define what the Jewish community should be, should say, should think. It was power, more than Judaism, they were concerned about. That’s where I think the real force lives.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →