MAGNIFICENT OBSESSION

Following his sinister Hollywood sequel, Alien: Resurrection, Jean-Pierre Jeunet returns to the streets of Paris with Amélie – a giddy love letter to the city and cinema itself. Ray Pride talks to Jeunet about making one of the most successful French films of all time.

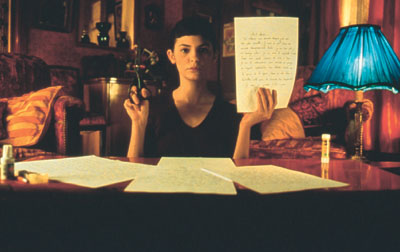

Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Audrey Tautou. Photos: Bruno Calvo.

These are the days we live in. Joy is suspect. Bliss? Mere entertainment. Jean-Pierre Jeunet, coming off of years spent in an inventive, if dour, collaboration with Marc Caro, made the grim and relentless Alien: Resurrection in the U.S., then returned to France to work on a lighter notion – a gesture of independence from Hollywood, from his creative partner, and from contemporary French cinema. The result has broken France’s box office records, sparked deep conversation and even suffered a modest backlash: Denied a slot in Cannes, his newest work Amélie, was offered an open-air screening. "Why should I show my film in a parking lot when it belongs in a cinema?" demured the 47-year-old writer/director. Le Fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulin – or Amélie, as it’s been shortened for North American consumption – is expected to be a rare arthouse home run. On his Web site, (jeunetcaro.online.fr) Jeunet asserted, after July test screenings in New Jersey, that Miramax will consider any return under $25-million a failure.

Before Amélie’s public debut at the ornate Elgin Winter Theatre during the Toronto International Film Festival, Jeunet and I are introduced. "No, no answers!" the shaven-headed, Tintin-shirt-clad director jokes. Like the most simple-minded of Cannes questioners, I reply, "Monsieur Jeunet: Expliquez!"

"No, no, it’s all a mistake," he says, grinning, "Everything is a mistake."

No, no, not exactly. Amélie is a patisserie of jouissance, more "breathless" than A bout de souffle. It would be reductionist to note that Jeunet’s fourth feature plays to Miramax’s most persistent theme: lovers kept apart by chance, brought together by fate. Think The Double Life of Veronique, Three Colors: Red, Sliding Doors and Serendipity. And now, Amélie. Yet, that’s a distributor’s taste – not an author’s voice.

A naïve, young gamine seeks love in the City of Light: Beyond that, there’s little more you should know before taking this zoom ride – and reviewers will be certain to spoil some of the better giggles and tremors for you. Let’s just say Amélie is a portmanteau agglomeration, a summary of narrative and fate, joy and despair – and then more joy. It’s filled with shivers: frissons of simple play atop a network of cultural and historical references. Some give little explosions in a French audience alone, while others are embedded in the collective consciousness of Western pop culture. It’s as swoony-spastic as Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player; as quartier-specific as the films of Prévert or Carné; and as forgivingly elastic of space as the films of Jacques Tati (the title Playtime would suit Jeunet’s film as well). It’s got the listmaking of Trainspotting; Peter Greenaway’s jam-stuffed frames, (but with a sense of humor); roguish pets with anthropomorphic longings out of Tex Avery; a box of long-lost boy’s toys precipitating a cascade of nostalgia, as in Nicholas Ray’s The Lusty Men. See: another list. And what about the bliss?

|

| Mathieu Kassovitz. |

It’s almost impossible to write well about bliss. Longing, yes. Regret, yes. Ugly souls and bad men – always a joy for actors to play – are a sweet sin to pen. But what of rapture, tranquillity or the contentment we all seek? As the phrase goes: "Happiness writes white."

"And who the heck said that?" I ask a half-dozen writerly friends, until I finally came up against a passage from Martin Amis’s London Fields and an unreliable narrator offering questionable insight within a miserable purview: "I think it was Maeterlinck who said happiness writes white: it doesn’t show up on the page. We all know this. The letter with the foreign postmark that tells of good weather, pleasant food and comfortable accommodation isn’t nearly as much fun to read, or to write, as the letter that tells of rotting chalets, dysentery and drizzle. Who else but Tolstoy has made happiness really swing on the page?"

Amélie has its moments of rascality, but the apocalyptic paranoia of Jeunet’s earlier films is absent. "You are going to see a very nice Paris in my film," Jeunet told his first North American audience. "Believe me, [in reality] it is raining everyday, we have traffic jams in the street, there is shit everywhere. I warn you if you are going on vacation."

He looks down to the front row: "You are too close to the screen!" Within minutes, distance is no matter, I think. Carried away, now a new millennium of movies can begin. Amélie is a delight – so fake it’s true, so manufactured, it’s genuine. Let only the most heartfelt of irony redound. It was a big hug of a movie to sleep with the night of September 10 and an even larger subject to tackle when Jeunet and I spoke later that week.

FILMMAKER: People seem afraid of making movies that are sheerly joyous, or mischievous yet affirmative. Why was it important to make a joyous film at this time in your life or your career? It’s not the easiest thing in the world. "Happiness writes white," goes the phrase.

JEUNET: [grins at translator] This guy is crazy! [pauses, amused] Maybe it’s because I did three dark features. When I worked with Caro, it was different. You have to have something to interest you in [all the work that goes into making] a film. But we are not brothers. We are not lovers. It is difficult to get the [shared] emotion. He doesn’t like sentimental things. The City of Lost Children, yes, is a dark film, and probably darker than most people imagine. It has taken me a long time to realize just how dark it is. After Alien, I realized I had never made a truly positive film. This was of interest to me; to build, rather than destroy, presented me with a new, interesting challenge. I wanted to make a sweet film at this point in my career and my life, to see if I could make people dream and give them pleasure. This is my personal film, one I dreamed of for a long time.

|

| Audrey Tautou. |

FILMMAKER: The film is often a barrage of notions, like channel zapping. You’ve got a film informed by 47 years of images and ideas, trying to turn scraps back into a scrapbook of memory. Did that form suggest itself before the characters and their overlapping desires?

JEUNET: I’m crazy, because I should have made five films instead. Now I am dry! I’m kidding – I did collect these ideas for 25 years. So now I have one [film] with 200 stories, the reverse of what you learn in school. It’s all a mistake!

FILMMAKER: It must have been a long process of writing and storyboarding, as well as editing, to get all those bits to mesh.

JEUNET: I did 18 drafts and a storyboard. But it’s not work, it’s pleasure.

FILMMAKER: You’ve said that your sensibility falls between Tex Avery and Marcel Carné.

JEUNET: Do you love Carné? Movies like La quai de brumes, Le jour se leve. I love those films. It’s an era of French filmmaking that matters.

FILMMAKER: That brings up the whole idea of typage – the wonderful, expressive features of actors from that era. Do faces and casting define a film’s world?

JEUNET: Today I tried to find some French faces – like Michel Simon, Carotte, Jean Gabin – the ones you see in films like those by Carné. It is not easy anymore. These were actors who had strange faces, but they knew how to play on screen. This was all before the Nouvelle Vague. After Nouvelle Vague, everything had to be "realistic." But I hate that. I’m always searching: I found the grocery man [in Amélie] [when casting] for a commercial.

But about Tex Avery, I had a passion for Tex Avery long ago. I began as a critic of animation, but I lost interest in all that after making my own shorts. There is only one shot in the film where I have literally quoted Tex Avery – the shot where an enormous amount of water falls.

FILMMAKER: In Amélie, you are working with locations and exteriors for the first time, but the way you’ve manipulated the images in postproduction "interiorizes" it all in a way.

JEUNET: I tried to work outside as if I was on a stage. We modified a lot of the reality. But it was important that the film take place in the Paris of today, not in some kind of timeless dimension. For example, we changed things on the walls, got rid of graffiti, added signs. We made sure there were modern objects, ugly things in the corners of rooms. Then in postproduction, if we did not like a face in one corner, "Bye-bye people."

FILMMAKER: Again, the idea of every frame like a painting.

JEUNET: Yes. I hate white skies.

FILMMAKER: But you can admire other filmmakers for capturing the modern world?

JEUNET: Yes, certainly, I appreciate realism. Erin Brockovich is not my style, but that is a wonderful film.

FILMMAKER: How do you feel when other filmmakers pluck details from your films? "Homage" can be such a fancy word for "stealing."

JEUNET: [widens his eyes, smiles] Ah! I have a good example. There is a director called Tarsem. He did The Cell. Before that, he did lots of commercials that looked like Delicatessen, especially one particular British beer commercial. It must be sad, working only with the ideas of other people instead of your own.

FILMMAKER: Do you know the bookstore in West Hollywood, Book Soup? You can see assistants piling up art books and photo books for their bosses to rip pages out and pin them to the wall for inspiration.

JEUNET: Yes, but Book Soup in Los Angeles – it alone is a place to go to see people!

FILMMAKER: The voiceover is breathless and breaks a few rules of its own. The audience I saw it with was laughing at everything you threw at them.

JEUNET: [One advantage with voiceover is that] you can get through small details very quickly. When I was in the editing room, I was a bit worried 20 minutes in. That is why, after 10 minutes, we see Amélie in the café, and the voiceover says, "The story will begin in a little bit." Don’t leave! Don’t go away!

FILMMAKER: Have you watched the movie with many audiences? At the first public screening here in Toronto that standing ovation was pretty breathtaking.

JEUNET: I saw the film many times in France, and at the Edinburgh festival. The other night, I meant to slip out after a few minutes, but I couldn’t. After that audience, I was ready to sign my next three films up for Toronto.

FILMMAKER: I can’t imagine someone like Emily Watson in the role instead of Audrey Tautou.

JEUNET: [shrugs] No, no. It’s just a little more French, a young girl. You’ve seen Breaking the Waves. Emily Watson could be Amélie. It would be the same film, with a different face.

FILMMAKER: So this film must have been on your mind a long time. It’s not like it was just a reaction to the scale or style of Alien: Resurrection.

JEUNET: I was already working on what would become Amélie. I didn’t know what the film was about, but I had plenty of ideas for scenes, situations, characters – many specifics. One day, it was clear. A girl decides to alter the shape of the lives of other people. That was all I needed.

FILMMAKER: So the film is a big collection of things. Amélie loves lists, and the voiceover shares the likes and dislikes of several characters. So you –

JEUNET: I love lists. I love collections! You have it right, I collect themes. I used a few of them in the film: Nino (Mathieu Kassovitz) collecting concrete footprints or the torn photo-booth strips. I used to have a box where I kept my story fragments. Now I store all the ideas and lists in my computer. But using the lists, it’s a delicate matter. They have to reflect the personal, yet they must also reflect things everyone shares.

FILMMAKER: Amélie says, "I like noticing the details that no one else does." And the movie is filled with opportunities, bursting with things. It’s a better use of digital technology than science fiction, adding little things to the frame – like that one perfect shot of a jet in the corner of a skyline early on.

JEUNET: That was just a lucky day.

FILMMAKER: Back to comics then. You’re obviously immersed in the French style of comic books, to use Jacques Tardi as a single example. There’s a perfectionism to every frame he draws, part reportage and part a beautiful world that reflects his fascinations.

JEUNET: We are friends. We speak a lot. We have the same passion for the imagery of the first World War. I would return from a location I had chosen around Paris, and I would look at the photographs and say, "Where have I seen this before?" And I would realize, Tardi had already drawn it!

FILMMAKER I don’t think anyone has ever made an I-love-New-York movie with as many locations as you have of Paris. There must be 80 or so.

JEUNET I wanted Paris to be there at the heart of the film. It’s Kurosawa who said, "Every shot should be like a painting," and I agree with that. Like Tardi, I am drawn to particular staircases, monuments, the elevated Metro trains. We start there, then clear the streets of cars, graffiti, make the city more aesthetic. Then, down to the final frame, digital postproduction lets us work on creating this Paris to the last moment.

FILMMAKER So did that ease the pressure on you, knowing you could make changes after principal photography?

JEUNET I can’t get used to the idea that I can’t control everything. With location work, there’s always something going wrong, and it makes me crazy – a car parked in the wrong place, someone making noise. I prepare extensively so that I don’t waste time. When we lose an hour or two because of things we have not foreseen, I am not amused.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →