NO-BUDGET NIGERIA

Jeremy Nathan investigates the latest African filmmaking revolution, one that has prospered through a DIY ethos and consumer-level digital equipment.

|  |  |  |

| VIDEOS, LEFT TO RIGHT: Felony directed by Teco Benson; Rumours by Agiulla Njamah; The Oracle by Andy Amenechi; and Crisis by Ndubuisi Okoh. | |||

A filmmaking phenomenon has been quietly emerging in Africa over the last 10 years: the Nigerian feature industry.

One could compare today’s Nigerian directors and producers to the American no-budget movement; like its North American cousins, the Nigerians are proving necessity to be the mother of invention. But unlike the American no-budgeteers, Nigerian filmmakers have found a way to circumvent the usual industry distribution channels, regularly making both new movies and a living. Relying on neither government funding nor television coin, the Nigerian film industry has forged a viable digital video revolution — a business model that all of Africa and indeed many other parts of the world could emulate.

Significantly for a country of over 130 million people — with over 16 million in its capital city of Lagos alone — the Hollywood machine is virtually absent. There are no cinemas in Nigeria, its old movie houses having been converted into a variety of Christian churches. If Hollywood films are available in any manner, they are sold on the street during “go-slows” (mega-traffic jams) on pirated DVDs. On almost every avenue in Lagos, instead, one sees a proliferation of video kiosks — small booths with outlandish posters, all selling the latest Nigerian film releases. Every week at least 20 new local videos are released, and each Monday in Idumota, the video distribution district of Lagos, video agents queue and hustle for the newest tapes and posters, and within minutes they are doing brisk business.

While films in the Yoruba language are the most prevalent, Hausa- and Ibo/English-language films are hot on their heels. These locally produced films cost $10,000 to $15,000 each, are generally produced within the space of a month and are in profit after two to three weeks of video release. Videos sell to the public through this network of video merchants for $3 each. One dollar goes to the producer, $1 to the distributor and $1 covers marketing costs. Most videos easily sell more than 20,000 units, and very quickly at that. The most successful videos sell over 200,000 units.

This new breed of Nigerian film is primarily shot on video in a variety of formats — even VHS. Postproduction occurs on Avids and Final Cut Pro. Unlike many West and Southern African films, Nigerian films do not yet win prizes at European and American festivals; they are also not funded out of Europe, particularly with French subsidies.

|

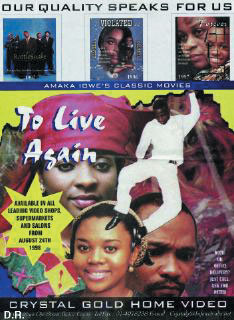

| Nigerian poster art. |

While low-cost production and post-production tools have undoubtedly contributed to this very recent explosion of feature filming, moviemaking has existed in Nigeria since the early 1970s, largely begun by actor-directors — particularly the Yoruba-led playwrights and actors — hailing from the country’s strong theater tradition. Sporadic at best, the films were the product of personal struggle, not government-supported initiative. Although cinemas existed, the Nigerian Film Corporation of those difficult days was more the personal fiefdom of African bureaucrats. Accordingly, film equipment and processing laboratories took a long time to get established in Nigeria. And with various military regimes ravaging the country, filmmaking never became an economic and cultural priority, as it did in Burkina Faso, Senegal and other West African states, supported strongly by the French government and its cultural policies. Nigerian filmmakers have always gone it alone.

This neglect, however, is actually one of the reasons for the current filmmaking boom. Nigerian television, which properly began in the late 1980s, quickly turned into a cheap repository for American soaps and sitcoms, and audiences became starved for local content. Says Femi Lasode, the leading music-video producer in Lagos: “People are really keen to see their amazing history and legends depicted on video. There are so many stories to tell that are important for Nigerians. We need to develop a sense of pride in our past.”

Film producers saw a gap and jumped straight in, making low-cost films which are marketed directly to viewers. Even today, television stations in Nigeria want local producers to pay them to broadcast their movies. As a result, television has become a way to promote the release of a new video title instead of a viable distribution outlet.

Like much film distribution in the Third World, piracy is a constant problem, particularly given that the films originate and are distributed only on video. So producers are perpetually seeking ways to protect their revenues. Some of these include shrink-wrapping the cassette to prove it is an original copy, or including raffle tickets inside the boxes to encourage people to buy the official cassette.

There are four main distributors in Nigeria. They control all aspects of distribution, from duplication, marketing and delivery to the collection of revenue. Until recently, distributors had focused on the mechanics of marketing and distribution. Now, however, distributors have begun to work closely with filmmakers, analyzing which genres are successful and frequently financing the films themselves. One of the largest distributors, Infinity Merchants, often invests or co-invests in the production of the films it distributes, thereby increasing its equity share. But many filmmakers still prefer to finance their films themselves, owning their own copyrights and just “renting” their distribution.

Most of Nigeria’s new video features fall into four clearly distinguishable genres: voodoo or ghost stories, love stories, historical epics and gangster stories. There is some controversy over the voodoo genre, and the NFVCB has entered the fray, frowning on the genre by “outlawing cultism, witchcraft, voodooism and the occult.” However, the genre continues to be produced and is popular with audiences. A fifth genre, porn, is quietly beginning to gain a following.

Charles Novia, a young producer-writer-director whose latest film For Your Love became an instant success, comments: “I specialize in love stories — the audiences really go for the drama. I follow a simple formula and it works. There is always someone, maybe a mother-in-law, who does not approve of the lovers’ relationship, which sets up the conflict. And in the end the two get what they desire most — each other.”

Femi Lasode, on the other hand, is known for his epic historical features. His latest film, Sango, deals with the reenactment of the life and times of a famous Yoruba king who reigned in the old Oyo empire prior to European colonization. “I have developed a large following,” he says. “People are really keen to see their amazing history and legends depicted on video. There are so many stories to tell that are important for Nigerians. We need to develop a sense of pride in our past.”

Intellectual critics frequently lambaste the new Nigerian filmmakers, arguing they are more concerned with money than with art. In fact, very few Nigerian films have been selected for FESPACO (the important festival in Burkina Faso) or Carthage (Tunisia), and very few are distributed internationally. However, given that most of these filmmakers are striving to produce better stories and are actively seeking African and international co-producers, it is just a matter of time before a young Nigerian filmmaker bursts onto the world cinema scene and makes a film that is both financially and critically successful. And there will be many others close behind.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →