ONCE UPON A TIME IN NEW YORK

Reflecting on their words in these pages 10 years ago, Hal Hartley and Nick Gomez discuss their ongoing lives as working independent filmmakers.

|

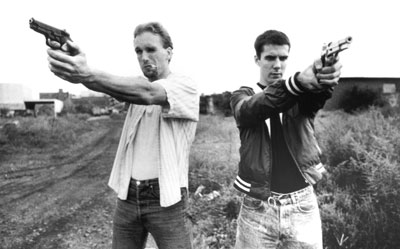

| Peter Greene and Adam Trese in Laws of Gravity. |

The centerpiece of Filmmaker’s debut Fall 1992 issue was a conversation between up-and-coming directors (and fellow SUNY Purchase grads) Hal Hartley and Nick Gomez. The interview took place on the eve of the releases of Hartley’s third feature, Simple Men, from Fine Line, and Gomez’s explosive no-budget debut, Laws of Gravity, from RKO Pictures.

At the time, Hartley had successfully built both a dedicated fan base of young viewers and an alternative financing model for his films, relying on foreign pre-sales, perhaps coin from PBS’s American Playhouse, and U.S. pre-buys. Gomez, on the other hand, was a founder of the rising New York production company The Shooting Gallery, and he used the heat from Laws of Gravity to travel with his producers into his second feature, the Spike Lee exec-produced and Island-financed New Jersey Drive. Both Simple Men and Jersey were budgeted in the mid-seven figures — worlds away from Gomez’s Laws and Hartley’s own low-budget debut, The Unbelievable Truth.

But that interview 10 years ago focused less on the usual new-release tub-thumping and more on working methods, ideologies, influences and friendships. As James Schamus wrote in his introduction, “For both Hartley and Gomez, the first feature was not simply the creation of an aesthetic object, it was also the construction of a mode of production, a way of working that ended up informing the very meaning of the film itself.” And Schamus detected in these directors’ early work traces of the anxieties that inform the lives of all indie directors: “Their characters are metaphorically not unlike most independent filmmakers — obsessed with work yet rarely working. Real work, as opposed to simply holding a job, is something of a criminal activity.”

In the years since that interview, Hartley has moved his filmmaking from Long Island to Manhattan, Tokyo and Iceland, while Gomez has modulated his style with his locations — from the frenetic New York of Laws of Gravity to the eerie Miami-scape of illtown to the broad comedy of the Hollywood lot in his studio comedy Drowning Mona. But both directors are still friends, and still engaged, passionate and working artists.

Without films to promote — the usual motivating factors behind interviews like this — Hartley and Gomez reread their old comments, as well as a few new questions we wrote for them, and reflected on the job of independent filmmaker with the benefits of a decade’s worth of hard-fought wisdom.

|

| Hal Hartley. |

Hal Hartley: I recognize myself very easily. I mean, [the old interview] makes it really clear to me that 10 years is not a very long time. I still say a lot of the things I said then. I think it’s probably true, though, that my business is still built very much upon my personality. Probably the hardest part of working is change, and the ways in which I like to work haven’t changed in 10 years.

Gomez: Your relationship to what you’re doing, regardless of what it is — a music video, a commercial, a feature or a short or shooting in 35mm or shooting DV — is always the same?

Hartley: Pretty much, yeah. But I do always want to give the people who are paying what they are after. That’s what’s fun about making rock videos. I like it when projects start from the producer’s requirements, when they say, “You know what we need? We need…”

Gomez: Liberating, isn’t it? There’s a freedom as long as you know and recognize that there’s a limit to how deep your involvement is going to be. But you know, [on director-for-hire jobs] people do keep coming up to you, even if you thought it was your own project, saying, “You know what we need?” That’s what happens in Hollywood, it becomes this collective “we” — the mass machine behind us all. There’s always a god behind the god behind the god.

Hartley: You can never grab hold of a particular approach to a specific creative problem because you’re constantly being redirected.

Gomez: I had a little bit of that with the last [film], that phalanx of faceless...

If you have a strong relationship to your material and you want to think that at all times you are in control, what can happen is that maybe without your even becoming aware of it, control ebbs away piece by piece. Any time you are second-guessed it is incredibly distracting. You have to stop, sit down and think about what they are proposing. For me, it defeated a flow that is necessary, something that we were talking about 10 years ago, which is embracing accidents and a certain kind of spontaneity.

But, Hal, what you’ve done with your work is to let your budgets go in a lot of different directions so that you can maintain the exact same relationship to and control over your work at all times.

Hartley: But it gets harder and harder.

Gomez: Why?

Hartley: It’s fashion. People go in and out of fashion. And a particular type of filmmaking, I think, goes in and out of fashion. We belong to the scene at a time when it isn’t fashionable to be an idiosyncratic writer-director [anymore]. It’s getting harder to work within a limited budget. Sometimes I feel like my notoriety rises faster than the cash value of the product I’m making. So for instance, it is extremely difficult for me to talk to the unions, because they want me to make a film for $3 million that, as a sensible businessman, I think ought to be made for half of that or else the investors won’t make their money back. So, of course, I’m encouraged to put more visible stars in [my films], which is a sensible approach, but then larger stars require more money up front. It’s always something.

Gomez: But that’s the game for everybody. You’ve got $70 million, and you’re still facing those same arguments. But what exactly is a “mode of production?” What does that [term] really entail?

Hartley: For me it’s always been the same. You’ve got to work, day in, day out, solving practical problems to get your film made. With No Such Thing, which was [made for] something like $5.5 million, I had to work the same way [as I did on my smaller films]. If my mode of production has changed, it’s changed geographically. I like to make films in different places. It’s not as localized now.

|

| Robert John Burke in No Such Thing. |

Hartley: How about you?

Gomez: The mode [I worked in then] I don’t work in now. I don’t get up every morning and write anymore. That stopped when I moved to Los Angeles. When I moved to L.A., I stopped thinking about the kinds of films that interested me. I stopped thinking about who I was, what my relationship was to my work, what I was maybe trying to express, what kind of mistakes I may have made in the past, what I had learned, what my successes were and how to move forward. What I did think about is getting a job. I pitched myself and my career in a direction that I thought — and was told — I needed to go in order, finally, to return to a mode that I was more comfortable with.

Hartley: So you had a long-term vision in a way?

Gomez: I went to Los Angeles with something very specific in mind: I wanted to do something that was completely different than what I had done in the past. I think that you can look at [Laws of Gravity, New Jersey Drive and illtown] and say that there’s a certain kind of direction and energy about them. I wanted to change all of that and try a completely different kind of energy. I’m not quite sure why. I think it was a combination of me feeling a little insecure about just being able to make a living. My budgets were getting smaller, and I felt like it was time to try and go after something a little bigger. I was trying to get rid of the demons that had been banging around all those years. I was trying to find something that had a whimsicality about it. But to do that, I had to work in a mode that I wasn’t comfortable with or hadn’t had enough experience with to do successfully. I didn’t know enough about the traps and dangers. I was being pushed along by this economic engine; I was going along for the ride, and it seemed like I was going in the right direction. But then when I got to the end, I realized, “This is not the destination I really had in mind.”

|

| Kevin Corrigan in illtown. PHOTO: GENE PAGE. |

You know, when a film doesn’t get the kind of reaction you want it to, it’s like the death of that one binding matriarch or patriarch in a family. All the people that you created a family with disappear, and you realize that the film was that grandmother, that matriarch, sitting up there. That’s the biggest lesson that I learned: “Oh, wait a minute — they were never there for me!”

Something I talked about [10 years ago], and I think I still do this in the projects I am attracted to — they are always going to be about people who are not grounded somehow. People trying to find a kind of family identity, or a group identity. People understanding what they’re looking for, or actually finding it or attempting to find it and realizing that it’s incredibly elusive.

Hartley: It’s difficult to do this work alone. Ten years ago, we were making films that were much, much smaller with a much smaller core of people.

Gomez: After the Shooting Gallery went belly-up, I’ve been on my own having to fight for everything. I get together with people on a project, a possible collaboration, but then everyone sort of moves on and does their own thing. I haven’t been able to hold onto a group that has stuck by me. It’s a nice thing to have.

Hartley: “How much does one need to fight to maintain one’s original impulse?”

Gomez: I interpret the question to mean a day-to-day aesthetic decision-making.

Hartley: Well, I think that’s impossible, remaining 100-percent true to the original impulses you had when you were sitting at your typewriter.

In the morning [during production] I do the diagrams, storyboards and stuff of what I am going to shoot that day. By lunchtime, I’ve already adjusted a lot, based on… everything. It seems to me that that’s what the directing part is: calculated, instinctual, hopefully graceful adjustments to particular problems.

The set is just people coming up to me with problems. “Hal, the trucks erroneously have been parked here.” “We can’t shoot these things the way we wanted to because the girl’s hair is going to take longer than we thought.”

So for two hours, alone, very early in the morning I get down with whatever my a.d. has told me I’m going to shoot that day. I don’t even like deciding what we’re going to shoot on a day. The night before, [the a.d.] tells me, “This is what you’re shooting tomorrow.” Then I just kind of meditate on that stuff in the morning so I’m ready for any degree of bending and twisting. By the end of the day, I very, very rarely come away with images that I have imagined at four o’clock in the morning, but I do hope that [the images I have shot] have sustained some sort of integrity with everything else I have been shooting.

Gomez: Your personality as a director is always going to completely dictate everything. No matter how much [of what you shoot] diverges from your original idea or your storyboards, it’s never going to be something that’s not you 100 percent.

Hartley: And that becomes one’s authorial voice.

Gomez: Precisely.

Hartley: Here’s another question: “James Schamus used to say, ‘The budget is the aesthetic.’ How have our aesthetics been affected by the size of our budgets?”

First of all, I’ve got to say, that’s my quote. I screamed it at Ted [Hope] while we were budgeting The Unbelievable Truth. And I saw him write it down on a yellow pad, and a few years later, James, I think correctly, used it as the banner for when they were starting Good Machine.

Gomez: I do believe I saw him in the T-shirt once.

Hartley: That “budget is the aesthetic” was very much the attitude when we made The Unbelievable Truth. We were all very new to the game at that point, and Ted was trying to bring his low-budget budgeting and scheduling expertise to the thing. I remember getting frustrated and telling him to stop being so protective of the authorial vision. If we only have $2,000, the script says one thing but we’ll just shoot it in a different way! We’ll make it work somehow. That [adaptability] takes faith in your ability to carry things out, but it also takes youth. I don’t know if I could shoot another film like The Unbelievable Truth in 11 days. I would get tired and bored.

Gomez: Because of the restrictions in what you couldn’t do?

Hartley: No, not really. I just wouldn’t have the energy. I mean, I basically didn’t sleep for those 11 days! I just can’t do that anymore. Do you remember the state of mind you were in when you made Laws of Gravity?

Gomez: Of course — it was exactly the same thing. You don’t sleep. But don’t you feel like you’re ambitious now?

Hartley: Well, you fight for different things, I think.

Gomez: You do choose which hills to die on, yeah. [As you get older] you become a bit of an old war dog. You’ve seen the battles before. That’s the thing about shifting aesthetics, and just sort of going back to the notion of a broader palette. As you go along you want to do different things simply because if you’ve done something once, why do it again? You have to always challenge yourself. I like to come out of the process knowing more about the material, the people I’ve been working with, myself and filmmaking than I did going into it. But I have talked to some guys who want to take [the filmmaking] to the limit of their knowledge, expertise and abilities, and keep it there, so they know exactly what they’re going to get on the other side.

Hartley: Yeah, I know what you’re talking about. Sometimes I look at my own films and think I would be a better filmmaker if I could somehow manage to get excited about delivering information. I don’t get excited about illustrating or simply presenting information. Of course I love telling stories. I like characters and stuff. But I’m more interested in choreography and, even more specifically, geometry. I like my shots to convey a kind of geometry. I guess if I could determine what some of my aesthetics are, it always seems they are in the place where curiosity and the best way of getting something done meet.

Gomez: Curiosity and practicality.

Hartley: Yeah, where they connect. Whatever I discover at that [intersection] seems to be the thing that really sticks and which I take on to the next thing. So when you talk about someone’s aesthetic, you are talking about the continuity of his or her curiosity. For me, I learn by doing.

Gomez: Curiosity is the key thing for artists, because once they stop being curious then they’re dead inside. But can curiosity expand beyond the practical? If your curiosity takes you to a place that’s completely impractical, then the desire becomes: How do I take the impractical and make it practical? How do I take the impossible and somehow make it possible?

Hartley: Well, I think in that kind of scenario, you might just be making films that are more avant-garde. The kinds of movies that we generally have made, apart from anything else they might be, are stories. Stories in most cultures and places are the same. So that’s where the practicality comes in. I’m curious about many things, but need is always the thing that’s changing.

Gomez: And you can’t get an “R” for all the things you’re curious about!

Hartley: And you can’t get the money for all the things that you’re curious about too, so I try to steer them together and see where they cross. And that’s another thing that might be a barometer to how successful you are as a filmmaker — whether your curiosity can meet the needs of the industry.

Gomez: Needs are interesting to think about in terms of being pure in your relationship with your work. Somewhere within your blood system, you have a very deep, strong attachment and desire to always express and create, which is a thing that I think I lost for a period of time and now I am trying to regain. My biggest fear is somehow finding myself in a cynical place that will somehow mute some of the original energies that I had. [Rediscovering them] becomes a process of almost revisiting adolescence.

Hartley: I think that the truth of the matter is — and this probably applies to any art — there is a danger to any strong conviction. That’s why it’s a strong conviction. As an artist, you have got to be schizophrenic to a certain extent, which is funny because the business really likes you if you are a director who is very agreeable. My biggest complaint about myself is that I always have been way too producer-friendly, because there’s a part in my head that is a producer.

I’ll tell you the truth: I cannot remember a day in my career after The Unbelievable Truth — where in most ways I didn’t know what I was doing to begin with — which I was happy to finish. I’ve never been satisfied with the work. And I know that I make it too easy for the producers. I’ve got this reputation of being a really producer-friendly director. But at the end of the day, what could it matter? I mean, a couple of more stressful hours with a crew would make pictures that would, at the end of the day, make a better film.

Gomez: You think so?

Hartley: I do, yeah. That’s really where I’m trying to discipline myself now, to exercise the ability to not be so overly considerate of the comfort of the crew.

Gomez: Yeah, that’s a tough challenge. I mean, there are those suicidal moments when you’re in the cutting room and you realize that you didn’t [spend enough time on a scene]. That’s the loneliness of being a director.

Hartley: I feel much more like an engineer than a director. I think John Sayles pointed it out years ago that it wasn’t very helpful to use that old analogy that filmmaking was like war. I think he was suggesting that war was somehow less democratic than most film shoots have to be, where you need the input of lots of other people. I think it’s in his book Thinking in Pictures. Filmmaking really is engineering. You are given plans and you have to build the thing that they say is in the plans. I don’t think I have it in me to change what my impulses are, but I have certain curiosities and needs that my work has to help. I feel like a director-for-hire all the time anyway, and I’ve always made my own films.

Read The Simple Laws of Filmmaking, Hal Hartley and Nick Gomez's conversation in the original issue of FILMMAKER.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →