SOUTHERN DISCOMFORT

At just 29, David Gordon Green is proving himself to be one of American film’s most prolific and singular voices. With his third feature, Undertow, Green returns yet again to the South, but this time he gets a little nastier. Stephen Garrett speaks with Green.

|

| Devon Alan and Jamie Bell in Undertow. PHOTO: DALE ROBINETTE. |

After tackling the coming-of-age drama George Washington and the moody, lost-in-love romance All the Real Girls, director David Gordon Green makes his foray into genre filmmaking with Undertow, a Southern gothic thriller about two Georgia boys on the run from an evil uncle. Bearing the expressionistic markings of his earlier films — a style which has been compared to the works of everyone from William Faulkner to Terrence Malick (one of Green’s current producers) — Undertow is nonetheless a departure for the 29-year-old writer-director, mainly because it’s not his own original material.

In the film, Jamie Bell and Devon Alan play Chris and Tim Munn, two young brothers living with their widower father John (Dermot Mulroney) in the deep woods outside Savannah, Ga. When their long-lost uncle Deel (Josh Lucas) suddenly comes back into their lives, John and the kids are instantly suspicious. And for good reason: Deel’s true motive for visiting is a handful of gold coins stashed away somewhere in the house. His greed — and the fact that he still accuses John of marrying the love of his life — sets in motion a brutally powerful conflict that becomes a modern-day odyssey for the two boys when they flee their uncle and push further into the wilds of the deep South.

Not one for witty dialogue or clever camera tricks, Green collaborates on every film with his longtime cinematographer Tim Orr to create an intensely evocative milieu saturated with emotion. At a crossroads in his career, Green has been balancing artistic integrity with studio-level budgets and stars. He’s also dabbled in advertising, signing with Chelsea Pictures in 2003 and directing a few TV spots in the anti-smoking “Truth” campaign as well as a commercial for Rheingold beer. Green is currently writing a script for Sydney Pollock while working on his new home in New Orleans — where he recently hunkered down for the hurricane instead of evacuating so that he could experience the extreme weather.

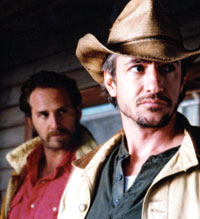

|

| Josh Lucas and Dermot Mulroney. PHOTO: KAREY C. WILLIAMS. |

David Gordon Green: It’s the shittiest, dirtiest movie. I always feel like I need to take a bath when I watch it now. I just remember what it’s like being there and it’s literally 110 degrees, and it’s just infested swamp, back-hill low country. It was a nightmare physically for that entire production.

Filmmaker: In your other films you have this strong sense of environment, but in this film it feels like that times 10. Was that written into the script or once you found a location did you say, “Okay we’ve gotta cover these guys in dirt”?

Green: It was location to a large degree. I think the more I found — the deeper I got into the regional location scouting in and around Savannah — the less realistic we decided to play the movie. It became more of a hyperreality: an exaggerated, Southern-gothic, drenched-with-dirt feel. And the production value was so much more enhanced by these junkyards and riversides that almost don’t look real — I mean, they look heavily designed, and this was such a low-budget movie I just thought it was going to bring in an enormous production value to the world we were trying to create, to make it a little bit more fanciful and a little bit more over-the-top.

Filmmaker: I was just thinking of that junkyard scene, when the two boys are running from Josh Lucas. It’s the biggest, most elaborate junkyard — it almost feels like a set, as though it was created to look that way.

Green: And yet it really is just this timeless place that we found — it’s just its own little time capsule that was great for us because we could artistically jump into the movie. For the production designers and the cinematographer and the costume designers, our whole method of approach to this film was to think of it as if it was a time when pirates still existed. A contemporary time, but if pirates still existed.

Filmmaker: There are a lot of stars in this film. Were there also a lot of non-actors as well?

|

Filmmaker: Do you notice, from a narrative and a character-development point of view, distinct differences among the various regions of the South?

Green: Definitely. There’s just such a huge difference between the Appalachian mountain country and the texture of Asheville, where we shot All the Real Girls, and then there’s the low-country coastal communities and islands of Georgia and South Carolina. It’s just a whole different attitude, different accent — equally as comforting and threatening. What the low country had for me is this kind of exaggerated feel to it. It’s not like a cartoon feel but more of a heightened reality that people live in and tell stories in and play music in, and the culture there… I mean, there’s an island right off the coast where they don’t even speak English. There are African tribal communities that actually live in tents. It’s just this odd, almost indescribable place.

Filmmaker: It does seem apt for a story that turns into an odyssey.

Green: Yeah, it’s an odyssey, very much inspired by stories like Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson books and Mark Twain, Huckleberry Finn–type things. When you get to the plot of this movie, there’s nothing remarkable about it. It’s a chase film, it’s gold coins, it’s boys on the run, it’s a boys’ adventure. But for me it’s a matter of trying to find something to latch onto and make identifiable and distinctive — with texture and atmosphere and character — to bring a spin to those conventions.

Filmmaker: Is this the first time you worked from someone else’s script?

Green: Actually, Joe Conway and I co-wrote the screenplay. It’s based on a story a kid told on a runaway hotline. We don’t know how much of it is actually true but we know that it’s based on a true story. The young man who interpreted the story was obviously on something and he embellished this very tragic and horrific life story. I was more interested in the exaggerated elements of his true-crime tale. And we took those elements and just exaggerated them even more and kind of adapted them to our own emotional sensibility.

|

| David Gordon Green directs Dermot Mulroney in Undertow. PHOTO: DALE ROBINETTE. |

Filmmaker: If this was a teen hotline story, how did you get ahold of it?

Green: It was just kind of word-of-mouth; the story traveled. Joe Conway wrote the initial draft based on the story as it had been interpreted to him.

Filmmaker: Initially this wasn’t a script brought to you to direct.

Green: Right. Before George Washington came out, Terrence Malick got in touch with me and said that his friend Joe, an English teacher at a high school in Austin, had written this script. Malick had seen George Washington somehow before it came out, and he sent me the script wondering if I’d be interested in collaborating on it — because Malick and Ed Pressman had just started their company, Sunflower, and were bringing projects to filmmakers, trying to get their hands dirty. So they sent me the script and I began communicating with the original writer; we went back and forth and eventually adapted it more to what I was interested in exploring.

Filmmaker: As you said, at it’s core it really is a fairly simple story. But of course you made it your own, which I guess was Malick’s intent to begin with.

|

Filmmaker: What about the film in its completed form? What are you most proud of in terms of the way things were interpreted or the genr is played around with?

Green: I think we brought a cinematic distinction to a genre that before Undertow was primarily seen as “drive-in movies.” I think a lot of the movies I looked to, and the crew looked to, in the design of this movie were the kind of movies that followed the success of movies like Billy Jack and Walking Tall. Not the big blockbusters — more like Macon County Line and Electra Glide in Blue. Those movies had kind of a catchy, campy value to them but they also had an identifiable story, something that interested me. And stylistically, I just really liked the technique.

Filmmaker: Do you feel that in American films the South has been misinterpreted, distorted or caricatured, maybe for the better, maybe for the worse?

Green: Absolutely. I mean you’re somewhere in between Deliverance and Fried Green Tomatoes. And a lot of that stereotype is totally deserved, and a lot of it is just Hollywood glamorization of the South.

Filmmaker: But it also seems like a lot of it is embraced in the South. Like The Dukes of Hazard, for example. I think some people really love that association, or at least play it up or laugh it off.

Green: Right. When I got involved with this movie, the pitch was I wanted to make the episode of Dukes of Hazard that David Lynch never got to make.

Filmmaker: I guess it’s all mythology anyway.

Green: It is, and that’s a lot more interesting to me. And Dukes is a great example because that’s what I grew up on. That’s still my favorite show. That’s as good as it gets to me, as far as being entertaining and funny and exciting. And it has Waylon Jennings hosting, commenting on everything. The way I grew up, listening and interpreting stories was taken less from literature and an academic approach and a lot more from sitting on a porch with some asshole who just lies a lot, embellishing every story and exaggerating everything he’s talking about. Ultimately that’s a lot more interesting to me. I’m just as interested in the interpretation of the story as in the story itself.

Filmmaker: At one point you were attached to adapt A Confederacy of Dunces, which I guess is now...

Green: Shelved.

Filmmaker: What happened with that? Is it just a cursed project?

Green: It’s been in development for years; it has a list of producers a mile long and a lot of financial and legal baggage that make it creatively claustrophobic. It’s not in a healthy position for production right now.

Filmmaker: That’s the closest you’ve come to working with major Hollywood stars in a huge production.

Green: The experience was amazing. The education was incredible; it proved to me how difficult it is to bring my approach to a production where people are looking over your shoulder. It makes it really hard for me to work in a way that I want to work, where my crew is inspired to work. I thrive on creative collaboration — where my sound mixer can chime in with his idea about dialogue, where my cinematographer can help me reconstruct a scene when it’s raining and redesign a scene when a location falls through. I like a production where people wear many hats. I don’t like to be told that I can’t move a light myself. I don’t like to be told that this isn’t a band of filmmakers. There’s a lot more of a structured, systematic, mechanical discipline in larger-budget projects.

Filmmaker: Did you have discussions with Soderbergh about that? Because I think of him as a rare exception, someone who has been able to maintain and protect his own stylistic integrity within larger-budget productions.

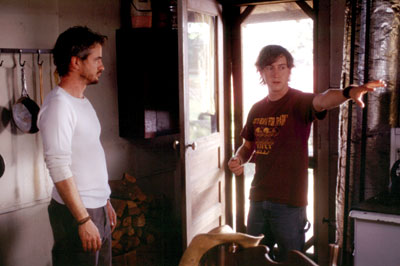

|

| Jamie Bell and Devon Alan. PHOTO: DALE ROBINETTE. |

Green: Outside of the financial and egotistical nuisance of the project there was a wonderful creative team that really wanted to make the movie the right way. They were in it in a gung ho way, and we found a way to communicate successfully and inspired each other to try new things. And that was a very strong, encouraging, creative process for about a year, and then it just got a little bit tied down.

Filmmaker: Is there a chance that you might still be going back to it?

Green: I don’t know. I put a cast together that I was super excited about and that has a level of financial common sense to it. But if it’s not going to be executed or supported in the creative manner that I think it should be explored then it’s not of interest to me.

Filmmaker: You had mentioned doing a big three-hour sci-fi movie in the vein of Tarkovsky. Is that something you might still do?

Green: If somebody would fucking give me the cash for it!

Filmmaker: And leave you alone with it.

Green: Yeah, that’s the thing. I’m at a point right now where a lot of my creative instincts are exceeding the budget that responsible financing allows. I have this crazy Western, this demolition-derby action-comedy, and a sci-fi movie — all of which are going to put financial pressure on me and my crew. It’s the financial pressure we don’t want, and it’s the creative freedom we insist upon. It’s hard. I’m at a point in my career where I’m trying to be somewhat strategic in the next move or two so that I can open doors and create opportunities like that, yet at the same time trying to work within the aspect of the industry that I love.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →