ALL OF ME

With Hedwig and the Angry Inch, theater director and performer John Cameron Mitchell makes a triumphant leap onto the center stage of independent film, reinventing the rock musical in the process.

By Adam Pincus

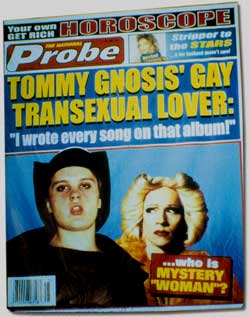

John Cameron Mitchell as Hedwig in Hedwig and the Angry Inch

The movie musical, wherein characters spontaneously burst into song, dance on the ceiling and sing in the rain, is not a genre that’s found much favor among independent filmmakers. Whether a result of its production demands, music-rights issues or possibly the unfashionable artifice of the form in an indie scene that often strives for "authenticity," few independent filmmakers have struck up the band. But something has clearly changed. This year’s Sundance Film Festival included two musicals – Cory McAbee’s black-and-white "musically driven space western" The American Astronaut and John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch. Mitchell’s film adaptation of his musical theater piece about a rock-and- roll German transsexual, went on to win the Dramatic Audience Award.

Of course, if one had listened carefully over the past few years, one could have heard the sound of the musical being revived. It is perhaps no surprise that Baz Luhrmann – whose previous films Strictly Ballroom and the rocked-out Romeo + Juliet contained plenty of singing and dancing – should open this year’s Cannes Film Festival with Moulin Rouge, an extravagant reimagining of the fin-de-siècle Paris hot boîte of the title as a place where Nicole Kidman and Ewen McGregor sing the songs of U2 and Elton John. But who would have thought of Mike Leigh or Lars von Trier as budding song-and-dance men. Yet Leigh’s opulent period musical of Gilbert and Sullivan, Topsy-Turvy, joined von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark, with Bjork’s haunting melodic sensibility and ingenuous screen presence, as new entries in the musical canon. And this year the Coen brothers worked source music – chain-gang rhythms and old-time string bands – into almost every scene of their "adaptation" of Homer’s Odyssey, O Brother, Where Art Thou? Even Ang Lee is seriously considering the production of a Godardian musical. But even closer to home for American independent filmmakers is Todd Haynes’s glam-rock epic, Velvet Goldmine, a film, much like Hedwig, that draws on the sounds and gender swapping of the late 1970s for its inspiration.

Hedwig is a collaboration between John Cameron Mitchell, a veteran of Broadway musical theater, and rock musician and songwriter Stephen Trask. Mitchell plays the title character, the glam-band-fronting survivor both of a botched sex-change operation and the betrayal of her lover and songwriting partner, a quasi-Goth pop star named Tommy Gnosis. Hedwig and her band, the Angry Inch, shadow Tommy Gnosis on his triumphant North American tour, doing parallel gigs in a chain of failing seafood restaurants. Hedwig is out for justice, recognition and, ultimately, reconciliation with her elusive "other half." The film is a love story of sorts, one in which its heroine finds a kind of self-affirmation.

Hedwig is a collaboration between John Cameron Mitchell, a veteran of Broadway musical theater, and rock musician and songwriter Stephen Trask. Mitchell plays the title character, the glam-band-fronting survivor both of a botched sex-change operation and the betrayal of her lover and songwriting partner, a quasi-Goth pop star named Tommy Gnosis. Hedwig and her band, the Angry Inch, shadow Tommy Gnosis on his triumphant North American tour, doing parallel gigs in a chain of failing seafood restaurants. Hedwig is out for justice, recognition and, ultimately, reconciliation with her elusive "other half." The film is a love story of sorts, one in which its heroine finds a kind of self-affirmation.

Mitchell and Trask began collaborating in 1994. Mitchell, an actor, was very familiar with Broadway, having appeared in Big River, The Secret Garden and Six Degrees of Separation. Trask was a musician/songwriter with a rock band, Cheater. The merging of these two worlds – rock and Broadway – seemed perfectly apt in a story about unification.

"The original metaphor [in Hedwig], about the origin of love, was from Plato’s Symposium," says Mitchell, referring to the Socratic notion that mankind was once split into two parts by the gods and that human beings have forever since been seeking unity and completeness through love. "Stephen wrote a song called ‘The Origin of Love,’ and things started happening, ideas started coming." Mitchell incorporated a character based on his brother’s baby-sitter, a German army wife, and they began performing the songs and characters in Manhattan clubs.

One of the first venues they performed in was called Squeezebox. "Because it was a drag club," Mitchell explains, "we had to [incorporate a] female character." As they continued to develop the piece in front of audiences, "the idea of the sex change, the Berlin Wall imagery and where my dad used to live all came up." (Mitchell grew up as an army brat; in the 1980s his father was Stadt Commandant in Berlin.) And Hedwig – the tube-topped baby-sitter – took over the piece.

Mitchell and Trask performed versions of Hedwig over the course of three years in rock clubs ("to keep the rock integrity," as Mitchell says) before mounting a stage production in the beautifully decrepit ballroom of a hotel on the West Side Highway, the Jane Street Theater, where it ran for over two years.

|

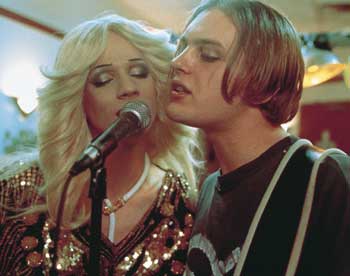

| John Cameron Mitchell as Hedwig and Michael Pitt as Tommy Gnosis in Hedwig |

As a stage production, a rock-and-roll musical loosely based on Plato about a sex-changed German army wife on the road with her band is one thing; as a film, relevant models were rare. "When I was adapting it for the screen, the only musicals that made sense to look at were the musicals of Bob Fosse," Mitchell adds. "All That Jazz, especially. It had that sense that a song could come out of the radio, or it could be sung in a rehearsal or it could be performed in a fantasy sequence. The music seemed motivated when it came up – as opposed to something like Singin’ in the Rain, which is using a convention where you can burst into song at any moment. I wanted something more real."

"Fosse’s films are the best example of combining theatrical and cinematic elements in a way that’s integrated," Mitchell continues. "In All That Jazz, almost every musical scene has a different style, but the acting and the story are always in the same style. The acting is very real throughout, but the camera [style] changes from scene to scene, and the performances are motivated by these shifts from a real place to one of fantasy. Hedwig," on the other hand, "leans more toward being in a real place [at all times], with two or three songs more in an internal place – a fantastic or surreal place. Once I realized Hedwig didn’t have to sing the same style of music in every scene, they could also be shot in different styles. What had to be constant was her performance. We’re seeing the world through her eyes; the view can change, but we have to believe that she’s real.

Realism may seem like an irreconcilable idea in the context of the movie musical. But Mitchell refers to advice once given him by an acting teacher: find a plausible motivation for the character who sings. "You’re saying something that you can’t say otherwise," Mitchell recalls. "You get to such an emotional level that you have to sing it."

|  |

| John Cameron Mitchell, left, and Stephen Trask. Photos by Richard Kern. | |

Indeed, Hedwig employs songs at key moments in the film in which the intensity of rock music is a particularly effective vehicle to advance narrative, character and emotional tone. And yet it’s interesting that, for a film that uses music to get to the truth of its scenes and characters, the predominant stylistic source for Hedwig’s music is glam rock, an idiom that is so much about surface, persona and play-acting. The film’s songwriting is much indebted to the early 1970s work of (as Hedwig dubs them) the "crypto-homo rockers": Lou Reed, Iggy Pop and David Bowie. And Hedwig and her band are, in appearance at least, as glam as it gets.

"Maybe it was my generation," Mitchell remarks. "I grew up in boarding school in Scotland in the early ’70s, when [the music scene] was all about glam. Artifice and performance – they’re inextricably connected."

Surprisingly, Trask was himself not an acolyte of T-Rex or of Bowie’s Diamond Dogs. But the narrative possibilities of rock lyrics have long interested him – cinematic songwriters like the Kinks’s Ray Davies, storytellers like Chuck Berry, even the meandering weirdness of Captain Beefheart. And the idea that musicians could create elaborate personae through their records wasn’t lost on him. "John Lennon, especially in his solo career, had a new ‘the Real Him’ every single album," he says.

There are a number of popular sources at work in Hedwig and the Angry Inch. But regardless of its glam style, its Fosse-inspired "realist" approach or its decidedly un-MGM characters, the film fits, finally, within the movie musical genre. "It is a musical, which sometimes has a pejorative aura for some people," says an unapologetic Mitchell. "It’s a musical in that the music pushes the plot and the story and the themes."

But, as Trask suggests, there are forces at play in our culture that has changed the genre’s meanings. "With A Hard Day’s Night, the musical started to switch its form," he says. "And I think it has something to do with a media-obsessed culture and the culture of celebrity." Lennon’s "New Real Him" has expanded to the point where a Courtney Love concert, fraught as it is with the subtext of biography and public persona, is nearly operatic. "Purple Rain, A Hard Day’s Night, even [VH1’s] ‘Behind the Music,’ are all musicals," Trask concludes. "I think there’s been a re-emergence of the musical because cultural obsessions have made it necessary. They just don’t look like musicals used to look like."

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →