LIVING LARGE

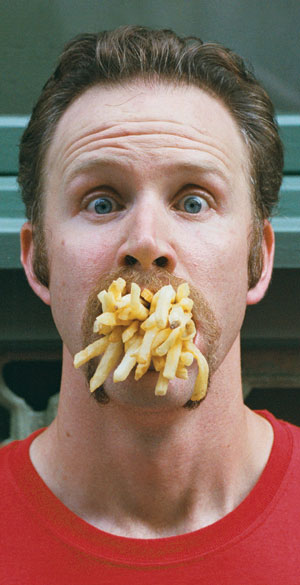

With his soon-to-be-trademarked handlebar mustache and his viewer-friendly affability, Morgan Spurlock is poised to become the next Michael Moore. In his documentary debut Super Size Me, Spurlock entertainingly eats himself into mortal danger in order to expose the perils of America’s fast-food obsession. Andy Bailey digests it all with Spurlock.

Super Size Me director Morgan Spurlock.

Provocateur Michael Moore didn’t have anything to do with the Sundance sensation Super Size Me, but his methods were a major influence on New York City–based filmmaker Morgan Spurlock, whose funny and infuriating documentary feature examining the obesity epidemic in America took the Best Director prize in Park City earlier this year. In the film, Spurlock famously embarks on a 30-day diet of nothing but McDonald’s fast food, supersizing portions when offered and realizing shocking weight gain and potential liver damage as he interrogates doctors, lawyers, dieticians, school lunch program mavens, Big Mac connoisseurs and former government officials about fast-food consumption. Complete with an on-camera rectal examination and a gastric-bypass procedure, it’s a gross-out blend of endurance art and guerrilla muckraking that Spurlock hopes will change America’s thinking about what it eats. Sundance audiences ate it up, guffawing at an animated sequence featuring Ronald McDonald frolicking with tots to the tune of Curtis Mayfield’s “Pusherman” and retching during the obligatory projectile-vomiting scene starring Spurlock’s Happy Meal. It seems only a matter of time before Spurlock’s handlebar mustache becomes as recognizable as Moore’s copious gut.

A former ballet student who grew up in West Virginia before attending NYU film school, Spurlock currently runs the Con, a small Manhattan production company that recently signed on to produce 30 Days, a Super Size Me–inspired reality series for the FX network. He resides in New York City’s East Village in a six-floor walk-up that he shares with his girlfriend, who appears in the film.

Filmmaker: First off, to clear up a rumor that made the rounds at the end of Sundance: Reps from McDonald’s showed up to serve a cease and desist order on the film. True or false?

Morgan Spurlock: Completely untrue. I would be willing to bet that reps from McDonald’s were in Park City and came to see the movie. Especially when people would come up to me [before screenings] saying there was somebody outside offering $250 for my ticket. Who’s going to pay $250 to see Super Size Me unless it’s somebody who has to see it?

Filmmaker: Has McDonald’s admitted to seeing the film at this point?

Spurlock: They said they haven’t in their statement. They said, “Although we have yet to see the movie, from everything we know about this film, we give it two thumbs down.” Could I ask for a better review?

|

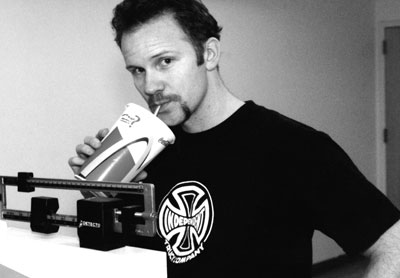

| Spurlock sizes up McDonald's. |

Filmmaker: Did the potential legal hurdles intimidate you during the production of the film? Did you ever worry that it might not be wise to single-out McDonald’s?

Spurlock: [That thought] was always there, like the elephant in the corner you can’t ignore. At the same time, it wasn’t going to stop us from doing what I believed we needed to do. As much as I was singling out McDonald’s, I wasn’t trying to pick on them — I used them as an example because they’re an icon. They’ve influenced every chain restaurant in the world. And they’re the brand leader. They’ve got 30,000 restaurants in over 100 countries on six continents, and now they own all these partner brands, like Chipotle Mexican restaurants and Pret A Manger. And I saw them as being the ones who could most easily institute change if they so wanted.

Filmmaker: It’s been reported that 99 percent of the version shown at Sundance would screen in the theatrical cut. What’s been taken out?

Spurlock: We had to change some music. Some clearances we weren’t able to get.

Filmmaker: You didn’t have clearance problems with the McDonald’s logos or the Ronald McDonald footage?

|

Filmmaker: Were you a fast-food kid?

Spurlock: Never. My parents never took us to eat fast food. If we did, it was a special occasion, like if we won a baseball game. My mother was a big proponent of sitting down and eating dinner at the table every day.

Filmmaker: Discuss the inspiration for the film. When did the idea hit you?

Spurlock: On Thanksgiving, in 2002. I was on the couch, all Thanksgiving-ed out, like Al Bundy with my hand in my pants, at my mother’s house in West Virginia. The news came on with the story from New York City about two girls suing McDonald’s. Spokespersons from the fast-food industry came on TV and said, “Listen, you can’t link our food to these girls being obese. Our food is nutritious.” I was thinking, You guys are getting a little ahead of yourselves. If your food is that nutritious, I should be able to eat it for breakfast, lunch and dinner for 30 days with no side effects. Alex [Spurlock’s girlfriend, a vegan chef] was immediately horrified. I ran to the phone and called Scott Ambrozy [the film’s d.p.] and told him the idea. He said it was a really great “bad idea.” That was our mantra for the rest of the film.

Filmmaker: How long did it take to shoot after the idea was formed?

Spurlock: We shot the core of the film in about three-and-a-half months. As soon as I got back to New York after that Thanksgiving, we went right into preproduction. I dove right into research, trying to figure out who we were going to interview. The hook [Morgan’s month-long fast-food binge] was great, but I wanted it to be a much larger examination of the obesity epidemic, which is a huge puzzle. It’s not like fast food is solely to blame. By the end of the following January [2003], we were physically filming — we filmed nonstop for six or seven weeks during my eating phase, when I was going to the doctors. After that, we’d shoot a couple of interviews every other week because it was impossible to try and schedule everyone during the 30 days.

Filmmaker: Was there reluctance on the part of anybody to speak negatively about McDonald’s?

|

Filmmaker: Would you describe it as a quick and easy shoot, or were there stumbling blocks?

Spurlock: It was fairly simple, because we were run-and-gun with a minimal crew. When we traveled it was just Scott and me. We wanted to keep costs as low as possible. He had his own lighting kit and his own camera, so it was very simple.

Filmmaker: Had you ever conceived of a documentary before?

Spurlock: This was my first feature as well as my first documentary. I wanted to make a feature film more than I wanted to make a documentary feature film. From that standpoint, I think it comes off feeling a bit different than your average documentary. I wanted it to be entertaining, and at its heart I still think the movie is a comedy, even though it’s a black comedy about an extremely serious subject. George Bernard Shaw said if you’re gonna tell people the truth, you’d better make them laugh or they’ll kill you. So we tried to create something that would convey a message that was humorous and entertaining — and let people take their guard down without feeling like they were being preached to.

Filmmaker: At what point did you decide you wanted to incorporate animation into the mix, and who’s behind the hilarious Ronald McDonald incarnations?

Spurlock: I loved the animation sequence in Bowling for Columbine. After I saw that, I really wanted to put animation in the movie, not just flat graphics. The guy who did our motion graphics is the supertalented Jonah Tobias, from New York. It was all After Effects animation, with the exception of three cartoon animation sequences, which were drawn by a guy who works at the Con named Joe the Artist. He did all the key frames. Then we had a company from Bulgaria called Zographic finish the animation.

Filmmaker: What sort of camera did you use, and why did you choose it?

Spurlock: We shot the whole thing with a Sony PD-150, because that’s Scott’s camera. We tried the Panasonic 24p camera, but it doesn’t have an inherent 16-by-9; you had to use an anamorphic lens. We also needed something that would be good in enclosed spaces and work well in run-and-gun situations. When we walked into a McDonald’s shooting, we didn’t have time to futz with the camera.

|

| Spurlock checks out the damage during his month-long McDonald's-only diet. |

Filmmaker: Did anybody try to stop you from shooting inside a McDonald’s?

Spurlock: A few times people told us to turn it off, but most of the time, especially when we left New York City, people didn’t care. Once you leave New York, people are nice! Outside of New York, we’d tell people we were making a movie, and they were like, “That’s cool, let me introduce you to the manager”!

Filmmaker: Why are Americans so fat, based on your own discoveries?

Spurlock: There are so many pieces to this puzzle. The biggest thing, I think, is that we’ve forgotten to take care of ourselves. We’ve gotten to the point that taking care of number one isn’t important, because of time, or work, whatever. People need to realize that everything they do makes a difference, no matter how small it is. Drink one less soda a day! There are people we interviewed who were drinking six-packs of Coke each day. Also, people don’t eat as families anymore. That was a huge thing when I was growing up, and it has a huge impact on kids.

Filmmaker: Your film suggests that America is slowly eating itself to death. Why is this? Is there a greater psychology at work? Is capitalism ultimately evil by nature?

Spurlock: Again, there are so many things at play. We feel unhappy, like we’re not in the right place, so we dive into food as an escape. We’re spiritually untapped, we’re not happy with our career, our friendships, our personal relationships. Food has become a comfort for everything. It’s easy not to exercise, and it’s very easy to eat. Eating makes you feel good, especially when stuff is filled with fat and sugar, the things that are not good for you.

Filmmaker: Does it have anything to do with our position in the world and the fact that there are McDonald’s to be found in every corner of the globe?

Spurlock: That’s a big part of the problem. People insist fast food isn’t to blame, but when it’s so pervasive that it’s putting mom-and-pop places out of business, and people have no choice but to get the Taco Grande…

Filmmaker: What’s your attitude toward fast food now? Have you succumbed?

Spurlock: I live in New York, where almost everything is fast food. I still eat burgers, but if I’m going to eat one, I’m not going to go to McDonald’s. I’ll go to Cozy Soup & Burger on Broadway, where it’s this huge, fresh-made chunk of meat that I know the chef [prepared] himself and threw on the grill that day. Or if I’m out in L.A., I’ll go to Tommy’s and get a big chili cheeseburger, or In-N-Out Burger, where you can get much fresher ingredients.

Filmmaker: There have already been several comparisons to Michael Moore and Bowling for Columbine. Is he an influence?

Spurlock: It’s a huge compliment, obviously. He’s a tremendous filmmaker and a great visionary and a great voice for our country. Yes, he’s been an influence, but there are so many others. I love Errol Morris and also Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, who made one of my favorite documentaries ever, which is Brother’s Keeper.

Filmmaker: Do you expect McDonald’s to litigate, and if so, are you prepared?

Spurlock: I do not expect them to litigate. But we’re prepared for anything. Who knows what’s going to happen? McDonald’s was involved in the longest lawsuit in the history of the English legal system, the McLibel lawsuit. It involved two activists in London who were handing out material accusing McDonald’s of manipulating people with their advertising, mistreating animals, etcetera. McDonald’s told them they couldn’t hand out materials that threatened McCancer. And McDonald’s took them to court in England. They were in court for a year and a half. When all was said and done, the judge agreed that McDonald’s did manipulate people through advertising, they did mistreat animals. But the activists had said libelous things about McDonald’s, and they were fined something like one thousand pounds. It was a travesty the whole thing went on that long, and McDonald’s never tried to collect the money from them.

Filmmaker: Do you believe there’s such a thing as a responsible corporation?

Spurlock: That’s something we address in the film. McDonald’s is a big proponent of personal responsibility — “It’s not our fault,” they say. But when a three-year-old kid watching television has no idea about whether or not he should eat at McDonalds, where’s the responsibility in that? What’s responsible about building playgrounds at your restaurants in areas where there are no other playgrounds?

Filmmaker: Talk about your production company, the Con.

Spurlock: We started the company in 2000 as the Interactive Consortium. Just like every company that came out during the tech boom, we started as an Internet company. Our goal was to create programming online and then springboard it off to other platforms, including film and television. I Bet You Will was the first show to go from the Web to TV, a huge accomplishment for us. It was a show that proved people will do anything for money — we’d go out on the street and bribe people to do funny things for cash on the spot.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that a lot of the Con’s clients are major corporations, including Sony and Viacom.

Spurlock: I’ve worked with some major corporations, and I’ve had good working relationships with all of them. There are always good people within the system.

Go to Sidebar: Is Super Size Me just an invitation to a super-sized lawsuit?

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →