ORIGINAL GANGSTA

Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was the original “black power” movie, a gritty and exciting tale of a black man on the run from racist cops. But although it was a huge financial success, director Van Peebles’s vision was simply too radical for Hollywood. Now, 30-some years later, Melvin’s son Mario has crafted a lively and affectionate homage to his father’s film with Baadasssss! Filmmaker Cheryl Dunye talks with Mario and Melvin Van Peebles.

|

| Actor-writer-directors Melvin and Mario Van Peebles at the 2003 Toronto Film Festival for the premiere of Mario's Baadasssss! PHOTO: MIGUEL VILLALOBOS. |

Rated X by an all-white jury!” was the tagline for Melvin Van Peebles’s incendiary 1971 feature Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. Released months before the studio-produced Shaft, Sweetback’s was not only the first blaxploitation movie but also one of the most influential, profitable and politically provocative independent films of all time. The tale of a black man on the run after attacking two racist cops, the film mixed an experimental style with a “power to the people” message that echoed the era’s Black Panther philosophy.

Just one of the many provocations in the movie was the appearance of the director’s 13-year-old son Mario in a sex scene with a middle-aged prostitute. Now, 30-plus years later, that son has grown up to make Baadasssss!, a loving homage to his father in which he casts himself as his dad struggling to make that radical film. Blurring docudrama with fiction and mixing comedy with politics, Baadasssss! represents another interesting turn in the younger Van Peebles’s career. An actor who has appeared in almost 60 television dramas and feature films, Van Peebles launched his directing career with the defining urban hit New Jack City and then went on to make the black western Posse and the Black Panther drama Panther. Baadasssss!, however, is a return to bootstrap indie production — it was shot in 19 days on a $1 million budget.

To interview father and son Van Peebles we asked director Cheryl Dunye, whose first film, The Watermelon Woman, tipped its hat with its title to the elder Van Peebles’s debut feature, The Watermelon Man. Dunye most recently directed the comedy My Baby’s Daddy for Miramax. She spoke to them separately by phone from her home in Philadelphia.

|

|

|

|

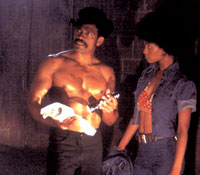

| Mario as Melvin in Baadasssss!

PHOTOS: MICHAEL O'CONNOR. |

Mario Van Peebles: My Baby’s Daddy — I got a kick out of that movie!

Dunye: Good.

Mario: Did someone else write it?

Dunye: Somebody else wrote it, of course.

Mario: And they brought you into it?

Dunye: Yeah, pretty late, and pretty much a mess.

Mario: I thought what was cool was the racial mix.

Dunye: Thank you. That’s what I at least tried to do.

Mario: You know, it’s always interesting to see what you can get away with. On New Jack City, for example, we talked about the fact that in ’90, ’91, most of the times if they would put us in an action flick, they would make us the police commissioner — that way you had a brother in a position of authority but he wasn’t sexually threatening. He’d be older, heavyset and with a receding hairline saying lines like, “Bring it in on budget or I’ll have yo’ ass!” Now that we were at the reins, we could put a white guy as the police commissioner and have him say, “Bring it in on budget or I’m gonna have your tail!” But I thought, I can’t do that, man — that’s reactionary stuff. So I put Russell Wong in there, who is a great-looking Asian brother, and Judd Nelson and Ice-T, but I played the police commissioner and said, “Bring it in on budget!”

Dunye: Where did your father’s movie Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song fit in within the context of black cinema at the time?

Mario: In the ’50s and early ’60s we were calling ourselves colored — the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, not black people. The subtext was that “colored” is just slightly different than “White.” “We’re not that different from you guys — c’mon, let us in, recognize our humanity.” Cinematically, that was reflected with us being the best we can be and being so overqualified — the Poitiers, the Dorothy Dandridges, the über-Negroes. You know what I mean?

Dunye: Completely. The niggerati.

Mario: Yeah. And what Melvin did was come along and make the first black-power movie. If Ali was the first black-power athlete and used the ring not just to box but to stand for something, Melvin was the first black-power director who used the screen not just to entertain but to stand for something. And when he got the idea for [the black community in Oakland] to be the star of the piece it was very heavy, because what he was saying was, “Power to the people.” And that of course was a Panther message.

Dunye: What was important for you to capture about the time your father’s movie was made?

Mario: What I wanted to do with Baadasssss! was not to parody the ’70s but to be true to it in spirit. The biggest thing was [capturing] Melvin’s sense of humanity. Here was a brother who was angry, who was pissed off, not at any human being but at systemic races. So when white folks watch my movie, they feel they’re with Melvin, they understand him and that someone else is the Man. You know, Melvin traveled [around the world], spoke Dutch and French and knew that we as a people, as human beings, have a tendency towards tribalism, be it black-on-black as in Haiti, or yellow-on-yellow as in Japanese fighting the Chinese. Or white-on-white as in the Irish fighting the British. Or brown-on-brown like Hindus and Muslims. And so while he was able to step over things, he never took any of those lines personally. That was key.

Dunye: Why did you choose the documentary form for this project? Or would you even consider it a documentary?

|

Dunye: So was filmmaking like home life for you? Instinct?

Mario: There’s a line in the movie: “He’s an ambitious little motherfucker, and he can handle it.” And I was an ambitious little motherfucker, and I wanted to handle it, because [my father] gave me the choice. He said, “Look, I could love you as a son, you can play and clown and go through all this teenage shit you want to go through, or you can work with me. And if you work with me, then you’re not a teenager, you’re an adult, and you’ll be on time and you won’t fuck up, and when I say ‘Jump’ you say ‘How high?’ And at the end of it, if this is what you want to do, you’ll know how to do it.” I can’t say I always liked him, but I said, “Shit, if I want my independence, who better to teach me than this cat right here?”

So I walked in those [filmmaking] shoes for a while and then went to Columbia and got a B.A. in economics. I worked for [Edward] Koch for a while in the Department of Environmental Protection, thinking that I could have a positive effect on the environment.

When I cleared up that childhood dream and decided I wanted to go back into film, I took my dad out to dinner. He said, “Great, let me give you some free advice: early to bed, early to rise, work like a dog and advertise.” He got up and left me with the bill. So I started doing little funky theater uptown in Harlem, and then [experimental theater company] Mabou Mines, and going to Stella Adler and doing plays. Eventually I found myself out in L.A., where I slept on the kitchen floor for about three years, keeping the overhead low, buying film [stock] and writing and directing shorts. Then I made a little short that caught some attention, and I got a film called Heartbreak Ridge with [Clint] Eastwood. And then I started directing [episodes of] 21 Jump Street and Wise Guys and eventually New Jack City.

Dunye: I looked at your father’s page on IMDb.com, and it says in the description, “He is everything: writer, director, producer.” Is that something filmmakers like us can aspire to in today’s filmmaking world?

Mario: You know, a while ago, in ’91, I did a cover of the New York Times Magazine with Singleton, Spike, the Hudlins and Matty Rich: the Black Wave du jour. Ten years later we did a photo shoot again — I think it was for The Source. And there were more of us this time. [At the end of the shoot] I said, “Look, I’m inviting y’all for dinner.” I called them up, they came over to my house — the Hudlins, [John] Singleton, Vondie [Curtis Hall], [F.] Gary Gray and Rusty Cundieff. We all started talking, and I said, “Look at us, man — most of us knew our fathers, weren’t in a gang, haven’t shot anybody, have had some education, and yet most of us aren’t getting to make movies about most of us! Our crowd is still considered by the studios to be the kids with the big sneakers, the 40 ounces and the baggie pants. The Italians started out with their Mean Streets and their hood films and graduated to the Apocalypse Nows, where no one eats pasta, but we aren’t being allowed to grow as filmmakers and do something about us — where we are culturally? Our choices are to start directing films about the dominant culture, or stay in the hood cinematically and do the black comedies and the hood flicks. That’s the glass ceiling. So I thought, [with Baadasssss!] I’m gonna make a film about a filmmaker, about a cat who can speak French, who’s not an athlete, not a rapper, not a boxer, and can work with people of all colors.

|

Dunye: And he left behind a new community, too — for you in the sense of his family, but also the community of filmmakers [that] the family who made the film invented too.

Mario: Yes. The first thing about filmmaking is having the child, but you know where we as filmmakers today often fall short? Getting that kid through college. That means going to Sundance and Berlin, where we won the Critics Award. Getting it out there. Sony Classics is opening us in two theaters, just like my dad’s flick. The question is, and I have no idea, is, Will the audience that [goes to] My Baby’s Daddy or Barbershop go to this?

Dunye: I don’t know. Is that the audience you had in mind when you made your film?

Mario: No.

Dunye: Who is your audience?

Mario: The luxury was that I could make this motherfucker with no audience in mind. [Although] sometimes with a bigger [budget] you’ve got to have an audience, I didn’t have to use the usual suspects. I made the movie with us in mind, with you in mind and me in mind. It’s about the freest filmmaking I’ve had the experience of doing.

Dunye: Showtime gave you that freedom?

Mario: What happened was, [president] Jerry [Offsay] was leaving, and he said, “You can take the money — it’s not a lot — and run if you want it.” And so I basically did that. I shot it in 18, 19 days. [Making the film was like] jumping off the diving board but not really knowing if there’s water in the pool — I made it with that kind of abandon. As long as I was in the piece and it was $1 million, they were cool. And then it was, “Oh, we sold it to Sony Classics and the foreign to Echo Bridge.” Now, what happened with you after My Baby’s Daddy? Are you being offered other material?

Dunye: You know, I’m just reconsidering everything completely. I’m living in Philadelphia right now and teaching at Temple, and I’m definitely reading some other scripts.

Mario: Did the movie do box office?

Dunye: It did about 18 [million], which is still up there.

Mario: And the budget was what?

Dunye: Twenty with advertising and stuff like that. My shooting budget was 15.

Mario: They were looking for it to make more.

Dunye: I guess. And it was Miramax. This was the first urban film completely done by Miramax, and Harvey just ran with it at the end regardless of what work I had done.

Mario: Did he do the scissorhands thing?

Dunye: Yeah. In that sense I’m trying to recover.

Mario: Wow! So that was Down and Dirty Pictures, then?

Dunye: Uh-huh.

Mario: Did you read that?

Dunye: The book? Uh-uh. I mean, I know it. [Laughs.]

Mario: No one touched [Baadasssss!] — no one. But again, I haven’t had that experience in four films, and this is my fifth!

|

| Mario and Melvin Van Peebles. PHOTO: MICHAEL O'CONNOR. |

Cheryl Dunye interviews Melvin Van Peebles.

Melvin Van Peebles: Have you seen Mario’s movie yet?

Dunye: Yes, I have.

Melvin: It runs it down, doesn’t it?

Dunye: It runs it down! It’s like, “Watch this film and go make movies!” And it really explains your connection to the birth of independent cinema — or “sweet baadasssss cinema.” Do you see what you did then in relationship to the American independent movement now?

Melvin: Actually, I don’t know much about cinema, or much about independent! I just make movies like I cook: I put in what I like, because in case other people don’t like it I’m gonna have to eat it for the rest of the week. You know what I’m saying?

Dunye: So what are some of the things you put in?

Melvin: There used to be a thing in Mad magazine called “Things You’d Like to See in Cinema but You Never Do.” Well, there was a whole bunch of things what I wanted to see, how I wanted to see the people projected. In ’57 I was driving cable cars in San Francisco, and one day I decided I was going to [make movies] myself. You know, people complain and all this, but let’s get real here — it beats the post office. With [Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song], when the opportunity came I finally felt that I had enough technical expertise and enough juice to do the things that I wanted to do, so I just stepped out to do it. But the usual impetus for my work is being bad-humored. That’s probably the most honest thing I can say.

Dunye: So what do you think about independent filmmaking today? Are you happy at all? The Oscars, everybody’s up there — or does [establishment recognition] take away from that “independent” passion?

Melvin: I don’t know about that. That’s their words. I just wanted to get the man’s foot out of my ass. [Laughs.]

Dunye: [Laughs.] Continually.

Melvin: I wanted it to be possible for you, even if it was just a dream, to be able to say, “I want to make a film.” I wanted to make it possible for young minorities — and at that time, women were lumped into “minorities” — to work. Everyone bad-mouthed exploitation films, but people did get to learn their craft. That’s what I wanted for our folks, and it has come to pass a little bit. A bumblebee does not realize it is aerodynamically unsound and can’t fly; the damn thing flies anyway because it doesn’t know it can’t. Well, with our sense of self, I felt it was important not to talk about it but to demonstrate it. And then there was the other weapon: the man has an Achilles pocketbook. I felt that if I could make something that made money…

Dunye: Do you think you’re owed anything?

Melvin: I have no idea. I really don’t think of it like that. You have to understand, for years it was very carefully kept from the folks the significance of what I had done, because what I did was very dangerous for Hollywood. If the word on the street is that a film can’t be made unless there are 24 people doing the such-and-such and the so-and-so, and then somebody comes along and does it without the 24 people, then there’s lots of people standing around not only with egg on their faces but jobs in jeopardy. So for a long time there was a major denial that I existed. I did the one thing a black guy can’t do — succeed without a master. When I finished the film, I had to hire me a white guy to pretend he was the boss to sell the damn film! You know, I had a three-picture deal with Columbia when the movie made that much money, and they got pissed off because I promised everybody “two for one.” I promised them that they could feel liberal by helping me and have their racist theories vindicated by my failure. When I didn’t fail, everybody got pissed off! You dig it? I’ve not had a real job offer since I made Sweetback’s. So I just went to Broadway and did very well in the theater. But it wasn’t a surprise, it wasn’t a shock. My feelings weren’t hurt. This is what you expect. And hallelujah, that made it possible for someone else.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →