APOCALYPSE NOW AND THEN

Last fall, journalist Michael Luongo arrived in Afghanistan expecting trouble. Instead, he found the beginnings of a vibrant film scene.

| |||||||

| |||||||

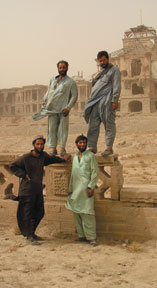

Before I headed to Afghanistan in September of last year to take photographs, I was given many warnings by journalist friends who had covered the American overthrow of the Taliban. Virtually all insisted that most Afghans would mistake a camera for a gun and I’d wind up killed. When I went there, though, I found that this scary prediction was far from the truth. I spent two weeks in Kabul virtually fending off the new friends I’d made, soldiers included, when I took my camera out.

I was there at the same time as filmmaker Stacie Teele, an acquaintance through mutual Afghan-American friends in New York City. She was making a film called Flowers in the Rubble, about Afghan children and the rebuilding of Kabul, but she had a unique viewpoint. She’s an American who grew up in Afghanistan and was forced to leave as a child when the king was deposed in 1973. A mother of three, she calls Afghanistan her “fourth child.” Her trip was a reunion of sorts, and she came with other Americans who had grown up in the country. Sometimes we would tell each other our adventures filming in the country, not only comparing notes about our own projects but discussing the filmmakers we’d met along the way. In the process I learned a lot about the variables that affect one’s ability to film in a country like Afghanistan. How did being a woman or a man affect the types of images one gets? What kind of equipment, with how many people on your crew, gives the best level of intimacy? And how did the experience of American filmmakers contrast with that of native Afghans working on their own film projects?

The work being done in Afghanistan by small, independent filmmakers runs the full spectrum. There is no single Afghan story; there are thousands. Each project I looked at for this article was highly unique, whether dealing with women’s health care, refugee families, educating children about mine safety or the dangers faced by journalists.

|

London-raised New Yorker Taran Davies and Afghan-American Walied Osman worked together recently on Afghan Stories, a documentary about families displaced by the 23 years of war in Afghanistan, and they depended on local hospitality during their stay in the country not only for food and lodging but to gather material for their film. “We would always live with our hosts for an extended period of time,” says Davies. They stayed with an Islamic elder in Faizabad, and after a few days he was comfortable telling his stories to them on camera, giving the work, says Davies, “an intimacy that I know wouldn’t have come across in the interview [otherwise].”

Osman says that working with a small handheld camera was “the perfect way to move around.” The Northern Alliance would trail the clumsy big-league news agencies, asking for money for access to nearly everything. It was hard for these news crews to get unique stories. But while this went on, Davies and Osman would simply slip into the local population, using small equipment, their wiles and Osman’s knowledge of the Dari language to get them through.

Handheld cameras and a cinéma vérité style aided Sedika Mojadidi and Erica Soehngen in making Dangerous Journey, a film about women’s health care, childbirth and the deplorably unsanitary conditions at Kabul’s Laura Bush Hospital. Soehngen explains that they used a small digital camera when filming in the hospital, but “always broke the ice” before bringing it out. As women, they were also allowed into a world where men, even male doctors, are completely forbidden. Soehngen says that she “never felt nervous about using a camera around Afghans.” Mojadidi, however, notes that “huge crowds would gather… mostly made up of men” whenever she was filming on the street. “Most of these people had never really seen foreigners,” she says, and some Afghans could not tell the difference between still photography and filming. Daniel Junge, who worked on the film No Strings, about a puppet-based mine-safety education program for children, says that sometimes men would stand in front of his equipment as if waiting to be photographed by a still camera. To get around this, Davies and Osman would sometimes simply let the camera roll while they talked to each other beside it. The camera would be filming a street scene, but no one would know it was on.

|

| Christian Johnson's September Tapes, which was shot on-location in Afghanistan. |

Still, the unstable climate in the country was hazardous for the filmmakers. Razaqi and Johnston used this danger to their advantage by incorporating it into their film. At the time of their work, Afghanistan had no banks. Foreigners had to carry thousands of dollars in cash with them, making them targets. Johnston tells the story of how five or six people with machine guns surrounded them: “They wanted our money and did not want us to leave,” he says. Although he was scared at the time, “the camera was rolling while all this was happening.”

Filming just weeks after Sept. 11, Taran explains that “the whole object was to avoid as much of the fighting as possible.” But this was impossible. In fact, the big Western networks put their lives in danger. Walied claimed that news crews, including CNN, sometimes gave money to the Northern Alliance to shoot at the Taliban so that they could report the news saying “live at war.” Osman “found this practice disgusting,” as it put soldiers and innocent Afghans at risk.

The war may have been over when Junge was filming in May and November of 2003, but there were still real dangers. He was working with OMAR, the Organization of Mine Clearance and Afghan Rehabilitation, which handles the country’s de-mining and mine education programs. “The whole country is a minefield,” Junge explained, adding that it still contains millions of the explosive devices.

For Mojadidi, being an Afghan woman was at times the issue. “I remember fighting with a lot of guys on the street,” she explains. Men would tease her, but sometimes there was outright hostility. “We had our hair covered,” she says, but that didn’t stop some men, many of whom were not used to seeing women in public, from yelling at her. “There are certain expectations of Afghan women,” she explains. At times it was hard for some people to even believe she could be Afghan, given her appearance, accented Dari, and her occupation. Many thought she was Iranian.

Soehngen, who is blonde and American, says that “she was lucky, in a way, not to know what was going on” when Mojadidi encountered problems. Ironically, Mojadidi found it easier to film in what would be considered “rougher” areas of Kabul rather than in the busy downtown.

The payoffs for intimacy are clear, however, and some of the filmmakers discovered things that never made it into the news. By working closely with the Northern Alliance, Johnston learned that American forces purposely allowed an area to be underpatrolled where they knew Osama bin Laden was hiding. The expectation was that the Northern Alliance would then find and capture him. Instead bin Laden simply escaped on horseback under a cloudy night sky so his movements could not be tracked. The Northern Alliance soldiers that Johnston worked with, he said, “were the only ones who really knew,” and this was “integral to the storyline” of September Tapes.

Mojadidi and Soehngen already knew of the problems at the Laura Bush Hospital, but it turned out to be far worse than they’d ever imagined. Touted by the current administration as a model for rebuilding, it lacks basic sanitation. “If you went to the hospital, you would be shocked,” says Mojadidi. “The stench will drive you out within a couple of hours.” But the women who work there were happy to tell their story, hoping for improvement in conditions. “I think, without exception,” explains Soehngen, “they wanted people to know.”

None of the filmmakers I spoke with would hesitate to go back to Afghanistan to do more work, in spite of the challenges. For some, like Razaqi, it’s an identity issue. “You see yourself as Afghan before anything else,” he says, “even if I spent half my time in Kabul crying.”

In Osman’s case, he went to Afghanistan because, he said, “I have to find myself in all of this, to see it with my own eyes and to be proud of who I am, my culture and my background.”

The Americans, too, were enamored of the country and its hospitality. Teele will return over the summer to work on a film about the upcoming elections. “I feel very comfortable there, and I definitely feel at home,” she explains. But it is not simply that she grew up there. “What is it about Afghanistan?” she says. “It’s the people. I am so in awe of their ability to recover after 23 years of war and oppression.”

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →