HOUSE RULES

Oscar-winning director Alex Gibney returns to white-collar corruption to examine the incredible rise and sudden fall of mega-lobbyist Jack Abramoff in Casino Jack and the United States of Money

By Jason Guerrasio

JACK ABRAMOFF. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES.

On January 3, 2006, lobbyist Jack Abramoff solidified himself as the latest Washington villain when he exited a Federal Court in D.C. wearing a black trench coat and fedora. For someone known as a movie buff and producer of the low-budget action movie, Red Scorpion, in the late '80s, it looked like Abramoff had cast himself as the menacing bad guy in his own cloak-and-dagger thriller. But even before Abramoff had donned his black fedora, Alex Gibney had an eye on the man they call 'Casino Jack.' Through Susan Schmidt's reporting for the Washington Post he learned of Abramoff's illegal practices - which included lavish trips and gifts in exchange for political favors, heading a scheme in the Mariana Islands that can be best described as 21st-century slave labor, and defrauding American Indian gaming tribes of tens of millions of dollars. Digging deeper, Gibney found a man driven to succeed by any means necessary, a hyperactive personality who charmed the pants off everyone he met (including Gibney) and had skills enabling him to manipulate Washington politics to a point where it may never be repaired.

Gibney is no stranger to white-collar corruption. Before making his 2007 Oscar-winning doc Taxi to the Dark Side, he received an Oscar-nomination for his 2005 film Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, an in-depth look at how one of the world's largest corporations became America's largest corporate bankruptcy. Like Enron, Casino Jack and the United States of Money takes the greed, deceit and cons at the forefront of the story and strips them down to present a human drama. Gibney walks us through Abramoff's rise as a College Republican alongside colleagues who would later have high-level roles in the Bush administration; joining the group Citizens for America in the mid '80s, which helped support the Nicaraguan Contras; to becoming a lobbyist in the mid '90s, doing everything from bribes to building fake companies to influence the political system; and ending finally with Abramoff sentenced to almost six years in prison for fraud, conspiracy and tax evasion. In his wake lay resignations (House Majority Leader Tom DeLay) and prison sentences (Congressman Bob Ney and Ney's Chief of Staff Neil Volz) with countless others on Capitol Hill rumored to have ties to Casino Jack, including then-President George W. Bush.

With a wealth of archival footage at his fingertips, Gibney not only shows how Abramoff became one of the most influential people on K Street, but highlights what he calls "the kind of wheel-and-deal nature that the Republican Party had become." What's most frightening is that even though Abramoff is behind bars it doesn't mean his tactics have been locked up with him.

Casino Jack premiered at Sundance and will open in early May through Magnolia Pictures.

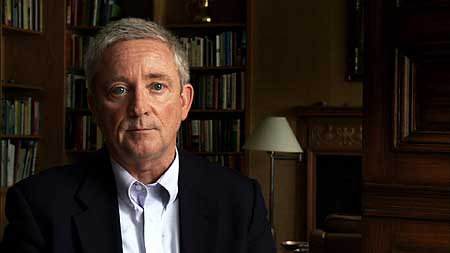

CASINO JACK AND THE UNITED STATES OF MONEY DIRECTOR ALEX GIBNEY. PHOTO BY: HENNY GARFUNKEL/RETNA LTD.

Since you screened the film at Sundance the Supreme Court has ruled to remove limits on corporate campaign spending, which was something that was in Abramoff's arsenal. Has that ruling in the Citizens United case become a dark coda to your film? Yeah. It's devastating. I just put a card about it in the end. Jack lost but he also won.

Before this ruling had you hoped that there would be some uplifting feeling at the end? I did, and I still hope that for the film but it's a much higher bar. I mean, I don't think people can lose hope, even with that horrible ruling. But man, as I was doing the movie I realized we all thought after Abramoff we enacted all of these reforms, and things haven't gotten better - they've gotten worse.

You've also trimmed down the film since Sundance? We had to take out the Medicare section. That was very hard for me to do because it's a great section that is so relevant to what's going on today, but it was a very dense section. It had an Abramoff connection but it wasn't that central to him. A thing happens in the cutting room - you get to a certain phase in the process and there are all of these great sections that you want to include but the film, kind of like a gremlin, starts telling you to pay attention to the story, follow your story, and our story was Abramoff. So by taking it out, which was very hard, it made the story better. And we're going to experiment a bit more with this one with the Internet, so when we release the film I'll take that whole section and release it on YouTube.

Was editing this difficult because you had so much good material? The editing process is always the most fun and the most brutal, particularly brutal at the end because the films are always too long. Particularly when you have director's disease. Director's disease is, "You know what, I agree that most films should be closer to 90 minutes, but for this particular film two hours and thirty minutes sounds like a better time for me," and you start fooling yourself. But I think there's a Rubicon crossed at two hours and we crossed it. The Sundance cut showed at two hours and three minutes and a couple of screenings they were great but we realized watching it again - Your brain goes on overload. Your brain goes on overload and you have to give people rest. We felt there was something kind of propulsive because this also is in Jack's character; it's full of enthusiasm and high energy - it's part of the con. So we developed a rhythm that seemed consistent with his character. But in the recut we just needed to pull out stuff so you could pause and get into the next [topic]. We let the music play more, cut down the amount of facts and figures. It's tough to find that rhythm because you want to be accurate, but the audience can't be working too hard that they get exhausted.

And you also have to examine why you're making a movie. You don't want it to just be a parade of interviews that turn into a lecture; you want there to be scenes that have other reasons to exist besides a kind of two dimensional information giving. If you see how luscious the Mariana Islands are you kind of get it and why it works for the Congressmen.

BOB NEY. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES.

What did you and your longtime d.p. Maryse Alberti talk about in regards to the film's look? Do you guys try for a signature style, or do you change it up for each film? Every time we go out we try to find a style, for the interviews in particular, and for this one there was a kind of a 'lobbyist backroom vibe' that we tried to convey. When we went to the Marianas we shot everyone outside because we wanted you to know immediately you were in the Marianas. With me and Maryse, it's always about finding a kind of atmosphere for a certain place, like when we shot in a casino in Louisiana, we actually had a Steadicam, so it was a little bit like the vibe from Casino. You feel like you're in the action. It was fun and it was movie-like, which was the other thing - Jack is a movie producer so we wanted it to have that vibe. When you do those aerials in the Marianas I wanted it to feel like Shangri-La.

With films like this one, Enron, and Taxi, what is it that first gets your attention and makes you think there's a movie there? This one was the story. Abramoff's story was so outrageous that it just seemed compelling. And it seemed compelling as a way of looking about what had gone wrong with government. I wouldn't have pursued it if his story hadn"t been so extraordinary. That was the spark. Same with Enron. Taxi was different but it ended up in the same place. Taxi was one where I was given the assignment. I didn't know what I was going to do. But in order to do a movie I had to find a story and so in each case the story is the thing.

Did you want to get Abramoff on camera? It was always my dream and we came very close to doing it but the Department of Justice thwarted us. I think Jack actually was willing.

You went to the prison? I went to the prison and I met him.

How many times did you see him? Three or four. I thought he was a very likable guy, very funny, good storyteller, very charismatic.

Did you get a verbal agreement from him that he'd be willing to be on camera? Yes.

Did the Justice Department give you a reason why he couldn't be in the film? The Department of Justice used carrots and sticks to persuade Jack not to be interviewed. We were forcing the door open through legal efforts and then the Department of Justice went to Jack and persuaded him to write me a letter saying that he did not want to be in the movie. But I know he wanted to be in the movie - he told me he wanted to. And I was working with his lawyer in order to make that interview happen. We shut down for a year trying to get Jack. But at the end of the day the Department of Justice intervened.

Why didn't they want him to be in the film? The legal argument is that you don't want your witness to be testifying to anybody else because you want to control his version of the acts and you don't want his testimony, if he had ever testified, to be impeached. And you don't want versions of his story floating out there in the ether that could be attacked by defense counsel. So that's their rationale. But, the fact is Jack had been sentenced and there was nothing abridging his First Amendment rights, so in my view what they did was improper.

When you realized you weren't going to get Abramoff on camera, were you unsure if you had a movie? Trying to get him came very late. You can't go into one of these things thinking you don't have a film if you don't talk to one person because then a witness can have too much power over you. You go in thinking, "I'm going to tell the story and I'm going to tell it the best I can." There's always a way to tell the story, and we started out telling the story through the detectives: [executive director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington] Melanie Sloan, [lobbyist] Tom Rogers and Sue Schmidt. [They were] the people who dug out the story. And the story changed because while waiting for Jack we ended up getting [Congressman] Bob Ney and [Abramoff business partner] Adam Kidan, and they're great. They weren't Jack, but they were pretty close. They both have been in prison and were Jack's partners in crime. So you never know what you're going to get; you just have to keep plugging and hope you're going to get something good.

TOM DELAY. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES.

From what you show in the film Tom DeLay is perhaps a bigger villain than Abramoff because he got away with it. I agree. It's unbelievable that he's gotten away with it. I'm surprised that he was never indicted. It really floored me. I mean, he had people like [DeLay Chief of Staff] Ed Buckham and others doing his bidding and you always have deniability in that context. The way the system works allows for an extraordinary amount of flexibility. In order to be found guilty of bribery there has to have been an explicit quid pro quo. But there's never an explicit quid pro quo - that's never how it works. Where [DeLay] and Abramoff saw eye to eye was once you become a kind of hardcore ideologue then anything that contradicts your beliefs is just hidden in plain sight. Jack would always tell me that "Willie Tan [who was involved in the Marianas sweatshops] is such a good guy, and he told me there was no abuse going on so I believed him." Okay Jack. But did Jack ever hire someone who spoke Mandarin to go out to some of the factories to really talk to workers when the foreman wasn't there?

When did the idea come to intersperse clips from Patton, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and The Manchurian Candidate? It comes out of the character. Jack is a movie buff so he kind of sees things cinematically. He loved to quote movies, so it seemed to me that was fair game. That was a way of finding a style for the film that would mirror his character.

The way you used the last scene from The Natural at the end of the movie is really jarring: showing a memorable cinematic image of America's pastime during a voiceover explaining how America's political system is failing us. It's a funny thing and we debated a lot about it. It's kind of a coda to the film but The Natural, as written by Bernard Malamud, is a story of corruption. There's a happier ending in the Robert Redford version, but when [So Damn Much Money author] Bob Kaiser says, "The national pastime is not baseball, it's making money," that seemed like a grand visual metaphor for this idea that all of us think that we're going to be wealthy some day. The sparks coming down on the ground are like pennies from heaven until you realize that it's all kind of a dupe; you see those fans cheering in the stadium and it's like we're all being duped. So there's something fundamental about that spectacle we all believe in. We all believe in the American Dream - that's [Redford's character] Roy Hobbs, the American Dream - but in fact the American Dream at times can be a con because we don't want to ever say to the people in power, "You are abusing that power." And that's because we imagine we're going to be in power someday and we don't want anyone to put checks and balances on us.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →

HOW THEY DID IT

PRODUCTION FORMAT: Digital HD.

CAMERA: Panasonic: P2, Varicam,

HDX-900, EX-3.

TAPE STOCK: DvcPro HD when applicable.

EDITING SYSTEM: Avid Media Composer 3.5.1.

COLOR CORRECTION: Pandora Pogle, not the Quantel Pablo.

GO BACK & WATCH

ENRON: THE SMARTEST GUYS IN THE ROOM

Casino Jack isn't the first time Gibney's turned his lens on corporate greed. In this 2005 doc he examines the major players responsible for the collapse of one of the largest U.S. companies.

MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON

Nominated for 11 Academy Awards when it was released in 1939, Frank Capra's look at Washington politics through the eyes of a naïve U.S. Senator (played by James Stewart) is considered one of the first looks at the political system run wild.

THE NATURAL

Barry Levinson's classic look at corruption and the national pastime stars Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs, a pitching phenom in his late teens whose career is cut short after a freak incident. He returns to the game in his mid 30s and becomes one of the game's greatest sluggers with his bat "Wonderboy."